Guidance Notes for Tutors

advertisement

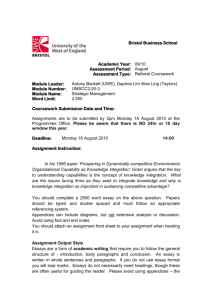

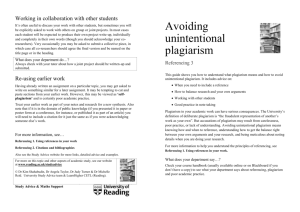

Guidance Notes for Tutors Section 5: Writing for Higher Education Introduction The quality of student writing in higher education has been the subject of critical attention in recent years. The topic was the focus of a major study by the Royal Literary Fund in 2006 that highlighted the struggle many students appear to have to write well-organised and cogent assignments and dissertations. In particular, students struggle with issues of structure and paraphrasing, and also to resolve a tension they feel between expressing their ‘own voice’ in assignments, and satisfying the conventions of academic writing. This is an issue that concerns many academics, and is currently being addressed by both the LearnHigher and the Write Now Centres of Excellence in Teaching and Learning (CETLs): the former, with the Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) project in the Academic Writing learning area; and the Writing for Assignments E-library (WrAssE) project in the Critical Thinking learning area; and in the latter CETL, the Student Authorship project, which addresses the issue of the relationship between writers and the facts, ideas and arguments expressed in their work. Both CETLs are interested in developing resources for students and staff that demonstrate how authorship in academic writing can be established. These resources will include examples of cogent writing, as it has been argued that students need to be shown what most tutors would regard as effective essays to become more aware of what is expected of them. This Section is divided into five Units: 1 Unit 1: Good Writing Unit 2: Writing Essays Unit 3: Writing Reports Unit 4: Avoiding Plagiarism Unit 5: Sample Essay As with other sections, the units offer a mix of information and student exercises. Units1, 4 and 5 offers sufficient material for a 50-60 minute teaching session on each of these. However, Unit 2 and 3 could be usefully combined over two teaching sessions; there are three student exercises in Unit 2, but only one in Unit 3. Teaching tips are included, and these are drawn fro HE tutors who have successfully used the material in the past. Answers to the quizzes and exercises are supplied in these notes, along with additional comment where relevant. 2 Unit 1: Good Writing Unit discusses the idea, that to be taken seriously, you must present valid evidence in assignments. Aristotle, around 350 BC, argued that persuasive rhetoric included Logos: appeals to logic to persuade an audience through sound reasoning. This is done by presenting reliable evidence, usually in the form of facts, definitions, statistics and other data, that has an appeal to the intelligence of an audience. Aristotle also believed that appeals to the emotions (Pathos), and emphasis on the credibility of the speaker (Ethos), were also necessary elements in rhetoric to persuade an audience to accept a particular argument. Although Aristotle applied his ideas to oratory, this ageless principle can be applied equally to written arguments, and, indeed, Aristotle’s ideas are the foundation for the current thinking in the communication industries. Aristotle’s ideas, however, appear to have overlooked by some academic writers, and many students, particular in the Social Sciences, are asked to read academic texts that can baffle, rather then enlighten their readers. The following extract is such an example: Garfinkel (1967) argues that the relationship between the act of representation and represented object is dialectical not unidirectional. The character of the representation changes in the attempt to explain the perceived nature of underlying reality while the object ‘changes’, in turn, to accommodate the language employed to represent it. Representation, in other words, is a dynamic, interactive process in which the ‘actor’, and the form of representation, that is language, ‘constructs’ some at least of the reality under investigation. This type of writing can intimidate students – or worse, lead them to imitate it. 3 But the best academic writing has always been accessible to all intelligent readers. The following extract by Anthony Giddens has been included to demonstrate this, and to illustrate how Aristotle’s Pathos element can be applied in academic writing. The Giddens extract As the changes described in this article gather weight, they are creating something that has never existed before, a global cosmopolitan society. We are the first generation to live in this society, whose contours we can only dimly see. It is shaking up our existing ways of life, no matter where we happen to be. This is not – at least at the moment – a global order driven by collective human will. Instead, it is emerging in an anarchic, haphazard fashion, carried along by a mixture of influences. It is not settled or secure, but fraught with anxieties, as well as scarred by deep divisions. Many of us feel in the grip of forces over which we have no power. Can we reimpose our will upon them? Arguably we can. The powerlessness we experience is not a sign of personal failings, but reflects the incapacities of our institutions. We need to reconstruct those we have, or create new ones. For globalization is not incidental to our lives today. It is a shift in our very life circumstances. It is the way we live now. Extract taken from: Giddens, A. (1999). Runaway World: how globalization is reshaping our lives. London: Profile Books. Students were asked to comment in the three areas shown below. Our comments are supplied, but Trans:it students may supply additional insights, which may prove equally valid and helpful. 4 The style of writing Clear, inclusive, and accessible writing. generally Good structure. Giddens is confident and assertive, which reflects his expertise and experience in this area. The impact of some Giddens uses words that connect with the senses of the of the words: single reader, or are related to physical action. There were terms out a few words that like ‘dimly see’, and words that connect with physical have a particular sensation: ‘shaking’, ‘driven’, ‘weight’, and ‘carried’. impact on you and try and say why this The author also uses contrast to create a tension (and is. interest) in the writing, e.g. It is not settled or secure, but fraught with anxieties, as well as scarred by deep divisions Note the term ‘scarred by deep divisions’. Giddens uses the word ‘scarred’ in a symbolic way to describe cultural divisions (and blemishes) among peoples of the world. However, the word also resonates with our sense of sight; we can visualize a scar, so the impact of the word is likely to be more profound and meaningful to us. 5 The way the writing Giddens addresses and engages the reader directly, or tries to appeal to the addresses our concerns. He uses words such as: ‘we’; ‘us’; reader. ‘life’; ‘lives’; ‘human will’. He also brings us into the discussion by posing a rhetorical question. Giddens recognizes the vulnerability and fragility of individuals who may feel swept along by global events. However, he also appeals to the more optimistic side of people, and presents the case for globalization as one of opportunity: Can we reimpose our will upon them? I believe we can. The powerlessness we experience is not a sign of personal failings, but reflects the incapacities of our institutions. We need to reconstruct those we have, or create new ones. 6 Unit 2: Writing Essays As this is an important issue for students, there are three exercises in Unit 2, and it may be necessary to spread these over two teaching sessions. The first exercise is to encourage students to focus on essay topics or questions, as a common cause of poor marks in assignments is that the student in question ‘did not address the question’. HE tutors will comment that students often attempt to tell all they know on a subject, but do not select and apply this knowledge to a specific area of enquiry or investigation. Students were asked to look at the following essay title and identify key words and the proposition. Evaluate the impact of the internet on practices for recruitment and selection employed by firms. Identify key words in the essay title The key words are: Spot the proposition in the sentence It proposes that the Internet HAS had an impact on recruitment and ‘evaluate’: selection; it stresses the words ‘the ‘impact’ impact’, which suggests there has ‘recruitment’, been one. ‘selection’ ‘firms’. (See comments that follow) (See comments that follow) The question asks students to ‘evaluate’ the ‘impact’ of the internet on both recruitment and selection practices. Students would also briefly need to define these terms to show they understand what is meant by them 7 The word ‘and’ is quite significant, as it suggests there are two separate processes here: the recruitment process and the selection process. Students would need to look for evidence of the impact of the Internet, negative and positive, on both of these processes. The term ‘firms’ is plural, meaning students need to look at more than one organisation to make comparisons, perhaps between firms of different sizes The proposition in the statement would have been harder for students to detect. It proposes that the Internet has had an impact on recruitment and selection; it stresses the words ‘the impact’, which suggests there has been one. . So students are being asked to think about whether or not they agree that this proposition is correct – they do have to agree with it. For example, if they disagreed with the proposition, they could argue that the Internet has had little impact or no impact on recruitment and selection – assuming they could find evidence to support this position. Provocative tasks The point is that assignment tasks, particularly essays, often invite students to take up and support a position with reliable evidence. There is unlikely to be a ‘right’ answer to many essay questions. Tutors are testing the student’s ability to research and weigh up evidence, take up a considered position, and present a particular argument in an intelligent and coherent way. It is worth emphasising that tutors may not agree with the position taken by a student, but will certainly respect a writer’s ability to argue their case in an intelligent way. 8 The two main positions that students might take in this essay, for example, are: Agree generally Agreeing with the proposition and Disagree generally Disagreeing that there has been an presenting evidence and summarising ‘impact’, or that it has been very why you agree. limited, and presenting evidence and discussing why you feel this to be the case. Students start to ‘evaluate’ when they do this, as they are making a decision on the proposition and, in this case, assessing the importance of the Internet to both the recruitment and selection processes. What else? In evaluating the impact of the internet, students would also need to weigh up the value (if any) of the Internet against non-electronic ways of engaging with the recruitment and selection processes. Description and Analysis A recurring tutor criticism of student writing is that there is often ‘too much description and not analysis’. This form of independent critical thinking may be unfamiliar to students …who in the past have been rewarded by their tutors for presenting accurate description of established ideas. The prospect of challenging the say-so of ‘experts’ can, at first, feel daunting, and even subversive. (Tutor quoted in Neville 2009, p.56) 9 This is particularly the case with discursive style essays, but it is important to emphasis to students that in science, technology and numerical disciplines precise description can also be a form of analysis. This can involve focusing on a topic in a detailed way. In many science and technology disciplines, for example, this focus can include the observation and identification of variables, element parts, and structures. In this context, the analysis is in the detailed description that you present. Students are likely to be asked in these assignments to: Classify Describe Identify Show how Or answer ‘what’ or ‘how’ style questions However, in this Unit students have been asked to decide if the essay extracts presented are predominantly description or analysis, or a combination of the two. The exercise is preceded by the following brief description of each of these categories: Descriptive Analytical Combine Description and Analysis You present a situation Analytical paragraphs Typically these in a factual way, usually often follow on from one paragraphs start with an presenting an overview that was largely introductory statement of the situation, which descriptive. (setting the scene), might include data to In these paragraphs, which is then followed back up factual you would by a deeper probe or statements made. explore/discuss the discussion, including implications or impact of examples, into or on the the situation earlier implications/impact of described. the situation in question. 10 Extract Description Analysis Both 1. The Internet is a system of connecting computers around the √ world. Linked to this is the ‘Intranet’, which is a way organisations can communicate internally. The population connected to the Internet in 1999 totalled some 196 million people, predicted to rise to over 500 million by the end of 2003. By the start of 2000, the daily number of Emails sent exceeded – each day – the number sent in total for the whole of 1990. 2. The Internet has had a significant impact on the way both firms and job √ seekers seek each other out. In Britain in 2000, for example, the Chartered Institute of Personnel estimated that 47 per cent of all employers were making use of the Internet for recruitment purposes (Dale 2003). In the USA the Association of Internet Recruiters estimated that 45 per cent of companies surveyed had filled one in five of their vacancies through on-line recruiting (Charles 2000). More than 11 75 per cent of Human Resources personnel in the USA are now making regular use of Internet job boards in addition to traditional recruitment methods of newspaper advertising and links with employment agencies (HR Focus 2001). 3. The main ways that firms use the √ Internet include developing their own web sites, making use of recruitment agency websites, or using ‘job boards’: external websites that carry sometimes thousands of vacancies that job seekers can scan. External recruitment agencies are increasingly specialising in particular types of niche vacancies, or acting as career managers for job applicants and helping to both place the applicant in the right job and to support that person during their career. 4. Job seekers too, use the Internet to contact prospective employers by placing their CVs or work résumés on √ to websites that employers can scan. A survey in the USA in 1999, for example, suggested that 55 per cent of graduates had posted their résumé on to an online job service, and that 12 three-quarters had used the Internet to search for jobs in specific geographic locations (Monday, Noe and Premeaux 2002). Some job seekers, with high demand skills, offer their labour in electronic ‘talent auctions’, with job negotiations, once a successful match has been made, facilitated by the Auction House representatives on behalf of the applicants. 5. The main advantages to employers of using the Internet for recruitment purposes are in the speed of operation, breadth of coverage, particularly if recruiting on a √ worldwide basis, and cost saving that can occur. Electronic advertising can quickly connect with job-seekers in many different places that might not otherwise be contacted by more conventional methods. Small to medium sized enterprises too, find that they can compete effectively electronically with larger companies and can begin to attract high-calibre recruits to their web sites, which might not otherwise be the case with more traditional methods of recruitment. With regards to cost saving, it has been estimated that expenditure on newspaper 13 advertising and ‘head-hunter’ fees dropped in the USA by 20 per cent as Internet expenditure increased (Boehle 2000). On-line recruiting, if it is used effectively, is also estimated to cut a week off the recruitment process (Capelli 2001). Large organisations, like L’Oréal and KPMG, use the Internet to recruit staff on both cost-saving grounds, and because they feel it increases their visibility and attracts high-calibre recruits. With KPMG, for example, the Human Resources staff was handling 35,000 paper applications a year, but decided to switch all their recruitment online from May 2001 to save time and printing costs (Carter 2001). Plan the structure of the essay Teaching Tip! If time permits, it can be a useful exercise to encourage students to think about how they might plan an essay structure around this essay title: Evaluate the impact of the internet on practices for recruitment and selection employed by firms. Whilst there is unlikely to be muck knowledge in the group in the content areas of the question, students may well have ideas how the question might be approached or addressed generally. The following comments offer one suggested way of approaching this task. 14 Evaluate the impact of the internet on practices for recruitment and selection employed by firms Write a clear introduction explaining to the reader what issues you intend to discuss (see example in Unit 2) Descriptive features: Outline the range of methods open to employers for staff recruitment and selection purposes, including the internet. More detail on the nature and impact of the internet generally in recent years, and describe how the internet is currently used for both recruitment and selection purposes by both employers and job-seekers (job-seekers can use the internet to their advantage too, to seek for vacancies) . Analytical features: Advantages of internet for both recruitment and selection purposes. Disadvantages of internet for both recruitment and selection purposes. Comparison with non-electronic methods of recruitment and selection. Conclusion: pull ideas together and reach a conclusion. How to reduce the word count Writing to a set word limit is a big challenge for many students, but it must be done otherwise can be penalised. Typically, students can lose a percentage of marks that matches the percentage overwritten. Trans:it students were asked to reduce the word-count in each of the three examples given without losing the meaning of the sentences. The adage ‘less is more’ often applies to all forms of writing; essays are no exception. 15 Example 1 To build a long term sustainable A long-term plan for change is change model to last 10 years is the needed that retains all the positive only way forward. In doing so, there is features of the organisation. need to retain all that is positive about the current performance of the (16 words). organisation but align this with an outwards facing strategic enabling approach. (46 words). Comment The original example contains a number of redundant and superfluous words. For example, “…build a long term sustainable change model to last 10 years”. ‘Long-term’ and ‘sustainable’ mean the same thing, and ‘long term’ becomes superfluous if we are given a time period. There are also unnecessary terms, such as, ‘In doing so…’ It also contains jargon that slows our understanding, for example, “… but align this with an outwards facing strategic enabling approach”. It is also written in the passive voice, e.g. “To build a long term sustainable change model to last 10 years is the only way forward”. This could have been written in an active voice, which inevitably cuts down on words, e.g. ‘Building a….etc. However, re-writing the sentence, cutting out redundant and superfluous words, is the best option. The re-worded sentence is clearer, sharper – and cuts down on words by nearly two-thirds. 16 Example 2 The power of fossil fuel companies is The power of fossil fuel companies is such that that they can influence such that that they can influence developed countries not to sign up to developed countries not to sign up to the Kyoto Protocol. Developed the Kyoto Protocol. countries are susceptible to the (23 words) influence of fossil fuel companies so if they not told to sign up, they are likely to give way to that pressure. (51 words) Comment This is an example of tautology: repeating the same word or sentence in an unnecessary way. The second sentence says much as the same as the first and can be cut. Example 3 The public’s knowledge of health is poor and more government funding The public’s knowledge of health is for health education is needed poor and more government funding (Atkinson 2004). for health education is needed Increased sums of money should be (Atkinson 2004). spent on courses to make people aware of personal health issues. (18 words) People don’t always know what they can do to take care of their health, so further investment is needed in training on health matters.(59 words) Comment: Same as for example 2 – there are two unnecessary sentences here! 17 Unit 3: Writing Reports Students were asked to ‘unscramble’ the five sections and match them with the ‘classic’ report structure presented to them, as shown below. A Classic Report Structure There is a Classic report writing structure for writing the main body of all reports, whether they are written for employment, academic, or other purposes: Conclusion Introduction Background Development Discussion Tells the reader what the report is about and how it is organised Sets the scene: puts the report into context, e.g. historical, economic, technical etc. Presents and analyses the problems or issues raised in the report Presents, analyses and discusses results or possible solutions to the issues raised. Summarises what has been learned, or makes suggestions, predictions or recommendations Exercise result: Introduction Background Development Discussion Conclusion Extract: D Extract: C Extract: B Extract: E Extract: A 18 Unit 4: Avoiding Plagiarism There is no doubt that plagiarism continues to be a hot topic of discussion in higher education. But it is certainly not a new phenomenon. And you can find a range of opinion among lecturers: from those who seize on plagiarism as a symptom of slipping academic standards, devaluation of higher education, and an erosion of everything they believe higher education should be; to those who feel that there is more than a little intolerance, hypocrisy and inconsistency around the issue. There are many academics, probably the majority, who oscillate between both positions, genuinely confused – about whether what they read in front of them in an assignment is plagiarism, carelessness, ignorance, misunderstanding, confusion or poor referencing practice. They can be driven to fury when they encounter blatant and wholesale copying, particularly if it comes during a particularly heavy and exhausting period of marking. Yet, when faced with the individual student, explaining his or her case for apparently plagiarising a text, can understand why it has happened. It is an issue that runs parallel to a debate with recurring questions about the purpose of higher education in the 21st century. Is an insistence on referencing about supporting a system and a process of learning that is a legacy of a different time and society? Are universities enforcing upon students an arcane practice of referencing that you will probably never use again outside of higher education? Or is there something deeper in the practice of referencing that connects with behaving ethically, properly, decently, and respecting others – ageless societal values that universities should try to maintain? Plagiarism, from this latter perspective, can be viewed as an attack on these values. A number of commentators (see Pennycook 1996; Thompson 2005; Neville 2009) have argued that plagiarism often arises from a lack of knowledge of referencing, rather than from a deliberate attempt to deceive. The four exercises in this Unit, therefore, present examples of when to reference – and when it is not necessary; where to cite in assignments; and what constitutes plagiarism. 19 Referencing Exercise 1: Is a Reference Needed? Situation 1. When quoting directly from a published source. Yes No √ Comment: The sources of all quotations used in assignments must be referenced. 2. When using statistics or other data that is freely available √ from a publicly accessible website. Comment: The sources of all statistics used in assignments must be referenced. 3. When summarising the cause of undisputed past events √ and where there is agreement by commentators on cause and effect. Comment: This can be regarded as common knowledge, which does need to be referenced. 4. When paraphrasing a definition found on Wikipedia, or √ similar website. Comment: This is ‘work’ in the public domain, so the Wikipedia site should be cited and referenced, e.g. (Wikipedia 2009). Many tutors would discourage students from drawing their information from sites like this, as the information shown can be unreliable. 20 5. When summarising or paraphrasing the ideas of an √ important commentator or author, but taken from a secondary source, e.g. general reference book. Comment: Students should only cite and reference the sources they have actually read or looked at – so the secondary source should be cited and referenced, e.g. (Clarke 2003, summarising Adams 2001): Clarke is the one that is fully referenced. 6. When summarising what your tutor has written on a √ course handout. Comment: The tutor should be cited and referenced, as his/her handout represents ‘work’ that has been presented into the public domain. 7. When including in your assignment photographs or √ graphics that are freely available on the Internet and where no named photographer or originator is shown. Comment: This is ‘work’ that is in the public domain. If no names are shown, the name of the site should be cited and referenced, e.g. (Bized 2009). 8. When emphasising an idea you have read that you feel √ makes an important contribution to the points made in your assignment. Comment: This is an important reason for referencing. 21 9. When summarising undisputed facts about the world. √ Comment: This is common knowledge (see 3, above) 10. When summarising an item of information you found on √ YouTube Comment: This is ‘work’ in the public domain and is ‘owned’ by someone. However, you may want to discuss with students the reasons why they would want to use information they found on such a site – is the information reliable? Referencing Exercise 2: Where Should the Citations Go? 1. A major study of British school leavers concluded that parents had a major influence on the kind of work entered by their children X. The children were influenced over a long period of time by the values and ideas about work of their parents. A later study reached the same conclusion, and showed a link between the social and economic status of parents and the work attitudes and aspirations of their teenage children X . Comment: The above extract refers to two different studies, so you need to cite both of these. You have some flexibility about where the citations should go. For example, the relevant citations could also have been placed after the words ‘study’ in lines 1 and 4. The important point is to make the connection between statement and source as obvious and clear as possible. 2. Climatologists generally agree that the five warmest years since the late nineteenth century have been within the decade 1995-2005, with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) ranking 2005 as the second warmest year behind 1998 X. 22 Comment: The sources of all statistics and information originating from named sources, such as the NOAA and WMO, should always be fully referenced. 3. It has been argued that federalism is a way of making sense of large organisations and that the power and responsibility that drives federalism is a feature of developed societies and can be extended into a way forward for managing modern business because “…it has been designed to create a balance of power within an institution. It matches paradox with paradox” X. Comment: If you use the term, “It has been argued…”, you need to cite who has presented this argument. As a quotation is included, you can show the source of the argument and quotation – assuming they are from the same source – immediately after the quotation. If the quotation is taken from a printed source, show the page number, as well as the author’s name and year of publication, as this helps others to easily locate the quotation in the source cited, e.g. (Handy 1994, p.98). 23 Plagiarism Exercise 1: Is it Plagiarism? 1. You see a useful article on an Internet site that will be Yes No useful in your assignment. You copy 40 per cent of the words from this and add 60 per cent of your own words. You don’t include a source, as no author’s name is shown on the site. Comment: you should always acknowledge the sources of items that have contributed to your own knowledge. If no author’s name is shown, you should reference the name of the website. The point that you used 60 per cent of your own words in the process is irrelevant. 2. You summarise a point taken from a course handout Yes No given to you by your tutor that contains secondary information, i.e. the tutor has presented an overview of the work of others. You do not reference the handout, as it has not been published outside the university and is just for the limited use of the students on the course. Comment: the handout is the result of work by your tutor and has been put into the public domain, albeit for a specialist readership. You need, therefore, to acknowledge the source in your assignment. 3. You are part of a study group of six. An individual essay Yes No assignment has been set by a tutor. Each member of the group researches and writes a section of the essay. The work is collated and written up by one student and all the group members individually submit this collective and collated work. 24 Comment: study groups are an excellent way to share and discuss ideas for assignments. But if an individual assignment has been set then each member of the group must write his or her own version of it. 4. You include the expression ‘an apple a day keeps the Yes No doctor away’ in your essay without a reference to a source. Comment: this is an example of a common expression, or aphorism, which does need to be referenced, as the source or origin of the expression has been lost in the mist of time. 5. You discuss an essay assignment with a tutor; not the one Yes No marking your assignment. The tutor has some interesting ideas and perspectives on the topic, which you think about, adapt and use in your essay. You do not reference the tutor in your assignment. Comment: only work, not ideas, can be plagiarised. ‘Work’ is when ideas are presented, manifested, or published into the public domain in some tangible way. We are influenced by ideas all the time; this is how we learn. If, however, the tutor had published his or her ideas, e.g. in an article, then you would reference this. 6. Your command of written English is not as good as you Yes No would like it to be. So you dictate to another student what you want to say in an essay, and that student writes it out for you, and you then submit it. Comment: you must write this essay yourself. If you feel you need help with English, you should seek advice from the learning development services at the University. 25 Plagiarism Exercise 2: More Plagiarism? Many students struggle to paraphrase or summarise academic texts. This can be because of time pressures, or they feel they cannot match the original, or because they only half-understand the original, so revert to copying. However, this can lead to accusations of plagiarism. This exercise presents a paragraph from a book on referencing and Trans:it students asked to decide which of these, if any, constitutes plagiarism within the definitions and explanation given in the Unit. Original extract: Academic study involves not just presenting and describing ideas, but also being aware of where they came from, who developed them, why, and when. The ‘when’ is particularly important. Ideas, models, theories and practices originate from somewhere and someone. These are often shaped by the social norms and practices prevailing at the time and place of their origin and the student in Higher Education needs to be aware of these influences. Referencing, therefore, plays an important role in helping to locate and place ideas and arguments in their historical, social, cultural and geographical contexts. Source: Neville, C. (2007). The Complete Guide to Referencing and Avoiding Plagiarism. Maidenhead: McGraw Hill/Open University Press. Example 1 Academic study involves presenting and describing ideas and being aware of where they came from, who developed them, when, and why. Knowing when to reference is particularly important as ideas, models, theories and practices originate from somewhere and someone. These are often moulded by the social norms and practices prevailing at the time and place of their origin and students on degree courses need to be aware of these influences. It can be said then that referencing plays an important role in helping to locate and place ideas and arguments in their historical, social, cultural and geographical contexts. 26 Example 1: Is this plagiarism? Yes. It is almost identical to the original and there is no attempt to identify the source. Example 2 Academic study involves not just presenting and describing ideas, but also being aware of where they came from, who developed them, why, and when. The ‘when’ is particularly important. Ideas, models, theories and practices originate from somewhere and someone. These are often shaped by the social norms and practices prevailing at the time and place of their origin and the student in Higher Education needs to be aware of these influences. Referencing, therefore, plays an important role in helping to locate and place ideas and arguments into their historical, social, cultural and geographical contexts (Neville 2007). Example 2: Is this plagiarism? Yes. Although the source is cited, the text has been directly copied into the assignment. This implies that the words have been written by the student concerned, which is clearly not the case. The student should have tried to paraphrase the original extract in his or her own words. Example 3 Academic study involves not just presenting Neville (2007) has argued that referencing can help a scholar to trace a path back to the origin of ideas. Ideas do not develop in a vacuum, but are formed by social, historical, economic and other factors. Referencing is important then, not just for identifying who said something, but when and why they said it. 27 Example 3: Is this plagiarism? No. It is a good effort to paraphrase the original extract and to acknowledge the source. Example 4 Academic study involves not just presenting and describing ideas, but also being aware of where they came from, who developed them, why, and when. It can be argued that the ‘when’ is particularly important because ideas, models, theories and practices originate from somewhere and someone. Neville (2007) has suggested that: These are often shaped by the social norms and practices prevailing at the time and place of their origin and the student in HigherEducation needs to be aware of these influences (p.8). So referencing plays an important role in helping to locate and place ideas and arguments in their historical, social, cultural and geographical contexts. Example 4: Is this plagiarism? Yes. The quotation used implies that the rest was written by the student, which is clearly not the case. Even though the source is cited, most of the text is a direct copy from the original. 28 UNIT 5: Sample Essay In Unit 5, students were presented with an essay, accompanied with tutor comment. However, an alternative teaching approach might be to present the essay without the accompanying comment, and encourage students to analyse it themselves. If you prefer this approach, the essay is shown on the following pages, and can be printed out for students. 29 Sample Essay What is the point of referencing? The reasons why accurate referencing is essential for academic work are not immediately apparent, particularly for students new to higher education. This essay will, therefore, examine why referencing is an essential part of academic writing and in the process address the question: ‘what is the point of referencing?’ There are three main reasons for referencing. Firstly, referencing helps student writers to construct, structure, support and communicate arguments. Secondly, references link the writer’s work to the existing body of knowledge. Thirdly, only through referencing can academic work gain credibility. This essay will discuss these three aspects of referencing in detail, examine their validity, identify how referencing affects a writer’s writing style, and show how referencing helps students to present their own ideas and opinions in assignments. Becker (1986) believes the construction of arguments is the most important function of referencing systems. There are four dimensions to this. Firstly, drawing on existing literature, academic writers can construct their own arguments - and adopting a referencing system supports this process. Secondly, it helps to structure the existing information and arguments by linking published authors to their respective works. Third, referencing helps academic writers identify sources, gather evidence, as well as show the relationships between existing knowledge. Finally, referencing also provide a framework to enable writers to structure their arguments effectively by assessing, comparing, contrasting or evaluating different sources. However, merely describing existing research, rather than producing their own contributions to the discussion, is inadequate for most academic writers. It is important for every academic writer to avoid this narrow-minded argumentation trap; academic writing is not just about compiling existing arguments, but adding new perspectives, 30 finding new arguments, or new ways of combining existing knowledge. For example, Barrow and Mosley (2005) combined the fields Human Resources and Brand Management to develop the ‘Employer Brand’ concept. When the argument has been constructed, it needs academic support – and only references can provide this required support. We all know that academic works are not about stating opinions - as that would be akin to journalistic comment - but arguments are supported by evidence, and only arguments presented with sufficient and valid support are credible. Hence arguments are only as strong as the underlying evidence: arguments relying on questionable sources are – well, questionable. Referencing also enables writers to communicate their arguments efficiently. The referencing framework allows them to produce a holistic work with different perspectives, whilst still emphasising their own positions; quotations, for example, help the reader to differentiate the writer’s opinions from others. Again, if arguments are badly referenced, readers might not be able to distinguish the writers’ own opinions from their sources. Especially for academic beginners, referencing helps them to adapt to the precise and accurate academic writing style required for degree level study. Neville (2007, p. 10) emphasises this issue of writing style, and identifies the quest to “find your own voice” as one of the main reasons for referencing. In academic writing, this requires developing an individual style that is neither convoluted nor convivial in tone, but which is clear, open but measured, and is about identifying and using evidence selectively to build and support one’s own arguments. Immanuel Kant said “Science is organized knowledge.” This short quote brilliantly captures the point that the primary mission of science and other disciplines is not to promote individual achievements, but to establish a connected, collective, and recognised body of knowledge. This is the most fundamental reason for referencing from a theoretical point of view. Hence some authors identify this as the principal reason for referencing: “The primary reason for citation [...] is that it encourages and supports the collective construction of academic knowledge” (Walker and Taylor, 2006, pp.29-30). 31 The writer’s references are links to this network of knowledge. Without these links an academic work would operate within an academic vacuum, unrelated to existing academic knowledge. A writer needs to show how his or her work relates to current research and debates in their chosen subject area. Referencing not only connects a student writer’s work to existing research, but clearly distinguishes the writer’s own ideas from established arguments –and failing to indicate that ideas are taken from the existing body of knowledge would be plagiarism. This is one of the five principles of referencing identified by Walker and Taylor (2006). Neville also identifies the link to existing knowledge as one of the main reasons for adopting a referencing style; he highlights “tracing the origin of ideas”, “spreading knowledge” and “indicating appreciation” (2007, pp.9-10), which leads to the next point. Referencing a work indicates that the writer finds the referenced material important: hence references create ‘academic clout’ in an assignment. In the global academic community a more-cited article will find more recognition. However, this practice is not without its critics. Thody, for example, calls this the “sycophantic” use of referencing - and it can certainly be used to “flatter your mentors” (2006, p.186). And Thompson calls this “ritualized obedience to the reigning authorities” (2003, p.27). So the important issue here is not about selecting references for their expediency value, but for their enduring quality. This brings us to the next point: credibility. Martin Joseph Routh said in 1878: “You will find it a very good practice always to verify your references, sir!” Correct referencing enables, therefore, the reader to check sources and verify conclusions. The issue of credibility is identified by commentators as a key issue in referencing. Nygaard, for example, identifies credibility as the main reason for referencing: “The goal of referencing is to enhance [...] your credibility as an author” (2008, p.177). Neville came to the same conclusion that “to be taken seriously, [a writer] needs to make a transparent presentation of valid evidence” (2007, p.10). Also the Academic Learning Support from Central Queensland University (2007) sees the credibility of arguments as primary motive for correct referencing. 32 References allow the reader to trace the source of the writer’s arguments, consult the original independently and verify whether the writer’s usage of the sources is valid. Some readers, for example, interested in a point in question, might want to verify the writer’s interpretation of a referenced work. The quality of references is, therefore, extremely important for the credibility of an academic work. Arguments are only as good as the underlying references untrustworthy and unreliable sources can even invalidate an argument, while reliable and dependable sources strengthen the writer’s argument. Finally, the writer’s selection of sources also demonstrates whether the writer has evaluated all important arguments and has a thorough understanding of the subject. Only a credible work that takes all important arguments into account will find acceptance in the academic world. So what is the point of referencing? This essay has presented three main arguments why academic writers have to adopt a referencing system: Firstly, it helps to structure, support and communicate arguments. Secondly, it links the work to the existing body of knowledge, although it is also important for writers not merely to present the ideas of others, but to contribute where possible with innovative ideas of their own. Thirdly, only referencing can give the argument credibility – and this is a particularly significant element for success in the academic world. References: ACADEMIC LEARNING SUPPORT (2007), Division of Teaching and Learning Services, Central Queensland University. Harvard (author-date) referencing guide. 2007 edn. Rockhampton, Queensland: Central Queensland University. BARROW, S. and R. MOSLEY (2005). The employer brand. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons, BECKER, H. S., (1986). Writing for social scientists. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 33 NEVILLE, C., (2007). The complete guide to referencing and avoiding plagiarism. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill/Open University Press. NYGAARD, L. P., (2008). Writing for scholars. Universitetforlaget. THODY, A., (2006). Writing and presenting research. London: Sage Publications. THOMPSON, A., 2003. Tiffany, friend of people of colour. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 16(1), pp.7-30. WALKER, J. R. and T. TAYLOR, (2006). The Columbia guide to online style. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press. End of Section 5. 34 References Giddens, A. (1999). Runaway World: how globalization is reshaping our lives. London: Profile Books. Neville, C. (2007). The Complete Guide to Referencing and Avoiding Plagiarim. Maidenhead: Open University Press. Pennycook, A. (1996). Borrowing others’ words: text, ownership, memory and plagiarism. TESOL Quarterly, vol.30, No. 2, Summer 1996, pp. 210-23. Royal Literary Fund (2006) Writing Matters. Available at http://www.rlf.org.uk/fellowshipscheme/research.cfm [Accessed 5 Jan. 2010]. Thompson, C. (2005). Authority is everything: A study of the politics of textual ownership and knowledge in the formation of student writer identities. International Journal for Educational Integrity, Vol. 1, No. 1. 35