491-107

advertisement

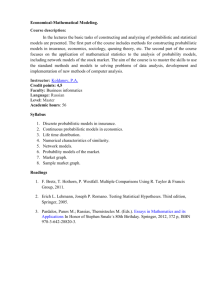

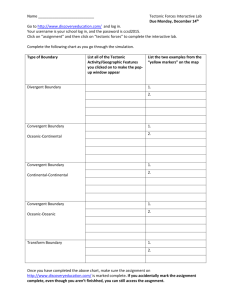

Probabilistic Uncertainty in Population Dynamics a* b b c OSEI, B. M. , HOFFMANN, J. P. , and ELLINGWOOD C. D. , BENTIL, D. E. a Departments of Mathematics and Computer Science, Eastern Connecticut State University, 83 Windham Street, Willimantic, CT 06226 and b c Botany and Agricultural Biochemistry, and Mathematics and Statistics, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT 05405 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Abstract: Analysis and characterization of either environmental or demographic uncertainty in population dynamics models are critical to species conservation and invasion. In particular, a probabilistic uncertainty methodology can be employed to analyze the fluctuations in environmental variables for model parameters of a prototype, generalized growth model in population dynamics. This generalized model encapsulates a myriad of sub-models. Estimates of the extinction time as well as the boundary classifications are determined. Key-Words:- Probabilistic uncertainty, population dynamics, environmental noise, generalized growth models. [8]). In this paper, we focus on probabilistic uncertainty. 1 Introduction The phenomenon of uncertainty in ecological modeling plays a very important role in spatial data and processes. Data on population dynamics often contain fluctuations, which are either due to environmental or demographic noise. In particular, environmental stochasticity can be measured due to fluctuations in the parameters of the model. For example, Croxal et al. [1] report that the Wandering Albatross exhibits fluctuations that cause an increase in their population to above their carrying capacities which in turn causes a corresponding negative decrease in their intrinsic growth rates. Fluctuations in model parameters can greatly impact on the conclusions made out of model predictions. There are two ways to incorporate uncertainty or noise in population dynamic models: stochastic and deterministic approaches. For the stochastic approach, noise is considered to be probabilistic ([2], [3], [4], [5]). In addition, depending on the modeling scenario, noise can be added linearly by some well know probability distribution (for example, Gaussian, Cauchy and exponential). On the other hand, for deterministic uncertainty, noise is considered as a small perturbation of the model parameters ([6], [7], 2 Suite of Growth Models We present a probabilistic uncertainty analysis for a suite of models, which are obtained from a generalized growth model of the form: dN a 1 b b N K Nb dt b (1) where K is the carrying capacity, b is a constant which describes the rate of growth and density dependence and a is a scaled growth rate [9]. This generalized model is an extension to the one originally described by [10] for two independent growth mechanisms. This generalization describes a suite of approximately 11 known sub-models for parameter ranges given in table 1 below. Based on equation 1 we will derive results for fluctuations due to probabilistic noise, in particular environmental noise. 1 where m( N ) and v( N ) are the mean and variance of the change in N per unit time t. Equation (5) is called the Diffusion equation (other names are FokkerPlanck equation in Physics and ChapmanKolmogorov equation in Mathematics). Based on this equation we can calculate the equilibrium distribution, bearing in mind that at equilibrium the flux across the surface is zero, that is, pˆ ( N , t ) must satisfy the ordinary differential equation 1 d m( N ) pˆ ( N , t ) v( N ) pˆ ( N , t ) 0 (6) 2 dN Equation (6) simplifies to the equilibrium probability distribution 3 Probabilistic Uncertainty Elderstein-Kershet [11] showed that the flow of particles across a surface undergoing growth is given by N ( x, t ) J ( x, t ) f ( x, t ) (2) t x where J ( x, t ) is the flux across the surface and f ( x, t ) is the growth function for the species. Let p N , t represent the probability density function for a population of size N ( x, t ) at time t. The flux equation (equation 2) reduces to p ( N , t ) J ( N , t ) (3) t N noting that f ( x, t ) 0 for probabilities since there is no growth. pˆ ( N ) Model type Exponential Momomolecular Logistic Gompertz Richards Generalized von Bertalanfy: Putter No. 1 a > 0, b = 1/3, K>0 Generalized von Bertalanfy: Putter No. 2 a > 0, b > 0, K>0 Generalized von Bertalanfy a = 0, b = 1, K>0 Linear a = 0, b = ½, K>0 Quadratic a = 0, b = 0, K>0 rth power Table 1: A list of parameter values and their model types m( s ) w( N ) exp 2 ds , N v( s ) 2 N v( N ) p( N , t ) . p( N ) N m( s) 1 exp 2 ds v( N ) N v( s ) (9) is the speed density and differs from the equilibrium distribution by the normalization constant. The integrals, y ( N ) p( N ) w( s)ds (10) z ( N ) w( N ) p( s)ds , (11) N N are functions that help to determine boundary classifications. Given any population dynamic model it is possible to relate the quantities in equation (5) to biological phenomena. For example, [112] relates this model to genetic drift. In this paper, we relate this methodology to population growth. Consider a general stochastic growth equation such as dN F (N ) dt (4) Incorporating this in the general particle flow, equation (equation 3) gives p N , t 1 2 m( N ) p( N , t ) v( N ) p( N , t ) (5) dt (8) which is the scale density function whereas The flux, J ( N , t ) , is now made up of two terms which are the diffusion term and the term that accounts for movement due to some external force. In short, J ( N , t ) is given by 1 (7) provided the integral exists and where c is a normalization constant. Other integrals that can be calculated to provide more information and answers to biological questions (see [12]) are as follows Values of a and b, K a < 0, b = 1, K=0 a < 0, b = 1, K>0 a > 0, b = -1, K>0 a > 0, b = 0, K>0 a > 0, b < 0, K>0 a > 0, b = 1, K>0 J ( N , t ) m( N ) p ( N , t ) m( s) c exp 2 ds v( N ) v ( s ) N (12) Suppose there is a biological parameter, say r that undergoes a fluctuation with variance , then equation (12) can be simplified in general as 2 N 2 2 dN f ( N ) g ( N ) z (t ) dt On the other hand, if this probability is zero (0) then that path is repelling. (13) f ( N ) rNf1 ( N ) and g ( N ) Nf1 ( N ) . discrete equivalent we have For ot a w e bl ra g te le rab eg int N) w( where z(t) is a random variable in continuous time and so that F ( N ) (r z (t )) Nf1 ( N ) , in )n (N p(n ) no t in ) int egra ble p(N y(N) integrable tegrable p(N) in t rable Naturally attracting Exit Not Attainable Fig 1: Boundary uncertainty Regular Attainable classifications for probabilistic (16) 4 Generalized Model with Fluctuating a (see for example, [12]). Biological conclusions based on the quantities m(N), v(N), w(N), y(N), z(N) and p(N) will be made from the boundary classification. Figure one is a diagram of the summary of the boundary classification [12]. Note that the boundaries are N 0 , N K and N . The boundary classifications can biologically determine if a population will go extinct in a finite time or as t . For example if N 0 is attracting then the population is approaching extinction as t (population is on the decline), on other hand N 0 is attainable if the population becomes extinct in a finite time. In general, a boundary is attracting if the probability of the limit of a sample path is positive as t , mathematically this can be represented by P lim N (t ) a 0 . z(N) not integrable m( N ) f ( N ) 2 p(N) is not integrable Naturally Entrance Repelling for some M 0 , then under some smoothness conditions for m and , X(t) satisfies the diffusion equation (5). Thus by the Ito’s lemma we have v( N ) 2 g N ble tegra 2 not in m( x, t ) ( x, t ) M 1 x 2 y(N) (b) 2 integ z(N) (14) Here f(N) is the growth component whereas the second term on the right hand side of both equations (13) and (14) respectively are the probabilistic (stochastic: continuous and discrete) components. It must be noted that z t is white noise and z(t), in the limit of small autocorrelations, is also white noise. Based on Ito’s lemma, both f(N) and g(N) can be related to m(N) and v(N) via the diffusion equation (equation 5). Given the Ito’s stochastic differential equation dX (t ) m( X (t ), t )dt ( X (t ), t )dW (t ) , (15) suppose X(t) is a solution of (15) and satisfies the following conditions (a) m( x, t ) m( y, t ) ( x, t ) ( y, t ) M x y teg rab le Nt 1 f ( Nt ) g ( Nt ) zt Consider the generalized growth equation (1) and let a fluctuate such that a a0 z (t ) then the differential equation corresponding to this fluctuation is given by dN a0 1b b N K N b N 1b K b N b z (t ) . (18) dt b Thus g(N) is given by g ( N ) N 1b K b N b and hence we can compute m(N) and v(N) by using equations (16) as m( N ) a0 1b b N K Nb b v( N ) N 2 2(1 b ) K b N b 2 Calculating w(N), p(N), y(N) and z(N) we have (17) 3 (19) a0 b s1b K b sb w( N ) exp 2 ds 2 21b b b 2 K s N s 2a exp 02 b p( N ) K b K N Nb 2 a0 sb1 ds K b N b b2 2 b b s 2 a0 5 Generalized Model with Fluctuating K The differential equation with fluctuating carrying capacity K, is given by (20) dN a 1b b a b 1b N K0 N b K 0 N z (t ) . (23) dt b b By using equation (16) we can find m(N ) and v(N ) b 2 2 2 N 21b K b N b b 2 N 2(1b ) K b N b 2 (21) as 2 a0 b 2 2 1 m( N ) We can show from equations (8) to (11), (20) and (21) that at the N = 0 boundary p( N ) N 2 2 2 a0 b 2 2 (22) y ( N ) N 1 2 2a0 z ( N ) N 1 2 2a0 Considering the case when b < 0, we note that w(N) is not integrable when a0 2 2 and integrable when a0 2 (24) a b 1b v( N ) K0 N b It can be shown by using equations (8) that a b s1b K 0b s b w( N ) exp 2 ds as b 2 N (25) 2 N b b N b b 0 exp 2 2b K 0 2 a K 0 2 a0 w( N ) N b a 1b b N K Nb b and w( N ) C when b 0 , where C is a constant. Calculating p (N ) by using equation (9) we 2 . On the other hand p(N) is integrable obtain when a0 2 and not integrable when a0 2 2 . In both cases y(N) and z(N) are not integrable. Thus the population is naturally repelling when a0 2 2 2 2N b p N 0 exp 2 2 2b a K0 p( N ) N 21b and attainable when a0 2 2 (see figure 1). The population will therefore never go extinct when a0 2 2 (approaching the carrying capacity) but will be moving towards extinction due to the stochasticity when a0 2 2 . The roles are reversed when b > 0, that is the population will therefore never go extinct when a0 2 2 but will be moving towards extinction due b Nb K0 2 (26) 2 b where p N 0 and b 0 . For b 0 , a K p( N ) 2 , where K is a constant. N By using a similar analysis as in section 3 above, it can be shown that there will be no extinction when the carrying capacity fluctuates for b < 0. Equation (23) illustrates this view clearly. As N 0 , the second term of equation (23) tends to zero (0) faster than the first term. The stochastic term vanishes faster than the deterministic term thus pushing the population away from the boundary and hence a repelling boundary. Conclusions can be made at only one equilibrium point, N = 0 since the other equilibrium point N = K is fluctuating. When b 0 then to the stochasticity when a0 2 2 . A similar analysis will show that the population will never go extinct in the neighborhood of the carrying capacity. 4 w( N ) constant p( N ) N 2(1b ) y ( N ) N b 1 conservation biology problems related to invasive species spread and endangered species modeling. Given the importance of the definition of the generalized models in evolutionary algorithms, we have discussed the concept of probabilistic uncertainty. We have adopted the methodology by [10] for analyzing probabilistic uncertainty and its usefulness in examining parameter variability. In particular, Ito’s lemma has been adopted in this case. Analyses of this generalized model shows that for a fluctuating growth rate, and for models where b 0 , at the N 0 boundary, the populations will be moving away from this boundary when the growth rate is greater half of the square of the variance in the fluctuations (increasing towards the carrying capacity). On the other hand if the growth rate is less than half of the square of the variance of the fluctuation then the population will go extinct in finite time. The roles are reversed when b 0 . At the carrying capacity boundary fluctuations in the growth rate does not cause any extinctions. When the carrying capacity is fluctuating the N 0 boundary is attainable when b 0.5 and thus the population will go extinct in finite time. Otherwise, the population will increase exponentially to the carrying capacity when b 1 . Allee Effect occurs when a population goes below a threshold level, forcing it to go extinct. This occurs when the intrinsic growth rate decreases as density or abundance reduces to low levels. There is no denying that a fluctuating growth rate will influence this dynamic. We are now considering the relationship between the variability in the model parameters and Allee Effect [16]. From our results, it is clear that the type and strength of the fluctuations also influences the dynamics of the phenomenon under consideration. (27) z ( N ) N b 1 Hence w( N ) is always integrable and p ( N ) is integrable and therefore the boundary is attainable. When 0 b 0.5 , the N = 0 boundary is still attainable and hence the population will be going extinct in finite time. On the other hand, when 0.5 b 1 then the population will increase unboundedly. 6 Discussion and Conclusion Both environmental and demographic noise in fluctuating environments have been partially responsible for the decline of many threatened and endangered species as well as invasive species and for the overexploitation and collapse of numerous living resources, including commercial fisheries [3]. We have shown in this paper that the type of model used and the population dynamic that is fluctuating can lead to varied conclusions. How can one therefore be sure whether the right model has been used especially in the presence of noise? For example, models based on differential equations, integro-difference equations neural nets, metapopulations, cellular automata and discrete simulations techniques have been use to predict spatial spread such as biological invasions (see for example [11], [12] and [13]). Thus, the choice of the right model is as important as the results of the simulation. To do model selection, one needs to derive appropriate “generalized growth dynamic models” based upon which the best candidate model for describing the phenomenon under consideration can be found. One such model selection technique is Evolutionary Algorithms. Evolutionary Computations (EC) have been inspired by analogies to evolutionary concepts (Darwinian evolution) such as recombination, mutation and selection. EC methods are exceptionally robust and pliable tools for search and optimization ([14], [15]). Here, a combined EC and information theoretic approach is used to orchestrate a competition among a community of candidate models that successfully evolves prototype mathematical models for a myriad of ecological and References [1] [2] [3] 5 Croxall, J. P., Prince, P. A., Reid, K. Dietary segregation of krill eating South Georgia seabirds, J. Zool. 242, 1997, pp. 531-556 Lande, R. Risks of population extinction from demographic and environmental stochasticity and Random Catastrophes, Am. Nat., 142, 1993, pp. 911–927. Lande, R., Saether, B.-E., Engen , S., Stochastic population models in ecology & [4] [4] [5] [6] [8] [9] [10] [11] conservation: An introduction, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2003. Foley, P. Predicting extinction times from environmental stochasticity and carrying capacity, Conservation Biology, 8, 1994, pp. 124 – 137 Nisbert, R. M. & Gurney, W. S. C. Modelling fluctuating populations, Chichester, Wiley, 1982. Basar, T. and Bernhard, P. Optimal control and related minimax design problems. A dynamic game approach, Boston, Birkhauser, 1991. Krivan, V., Colombo, G. A non-stochastic approach for modeling uncertainty in population dynamics, Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, 60, 1998, pp. 721-751. Bentil, D. E., Bonsu O. M., Ellingwood, C. D. Hoffmann, J. P. Deterministic uncertainty in population Growth, 4th IEEE International Symposium on Uncertainty Modeling and Analysis (ISUMA), CA, IEEE Computer Society Press, Los Alamitos, 2003, pp. 274 278. Osei, B. M. Ellingwood, C., Hoffmann, J. P. On a unified model for growth, Math. Biosciences, 2005 (in press). Schnute, J.A versatile growth model with statistically stable parameters, Can. J. Fish Aquatic Science, 38, 1981, pp. 1128-1140. Edelstein-Keshet, L. Mathematical models in biology, New York, McGraw Hill, 1988. [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] Roughgarden, J. Theory of population genetics and evolutionary ecology: An introduction New York, Macmillan, 1979. Hastings, A. Models of spatial spread: A synthesis, Biological Conservation, 78, 1996, 143-148. Higgins, S. and Richardson, D. M. A review of models of alien plant spread. Ecological Modelling, 87, 1996, 249-265. W. F. Fagan, M. A. Lewis, M. G. Neubert & P. van den Driessche. Invasion theory and biological control. Ecol. Lett.,5, 2002, pp. 148–157. Burnham, K. P. And D. R. Anderson, Model selection and inference: A practical information theoretic approach, SpringerVerlag, New York., 1998. Forster, R. M. Key Concepts in model selection and inference: Performance and generalizations, Journal. of Mathematical Psychology, 44, 2000, pp. 205-231. B. Dennis. Allee effects: population growth, critical density,and the chance of extinction, Nat. Res. Mod., 3, 1989, 481– 531. Acknowledgements This work was supported in part by grants from Eastern Connecticut State University, the NSF (DMS 9973208) to DEB, USDA Hatch and DOE Computational Biology grants to the University of Vermont. 6