Living Religion – Facilitating Fieldwork Placements in Theology and

advertisement

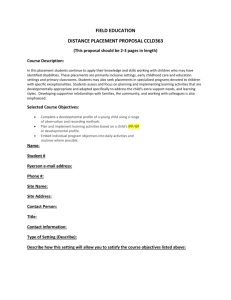

Project Report Denise Cush and Catherine Robinson Bath Spa University 1. Background to the Project Bid: Rationale Located in the context of a Higher Education institution with no particular religious affiliation, Study of Religions at Bath Spa University has a comparatively long history as part of teacher education before becoming part of subject-based degree programmes. As early as the mid 1970s, an integral part of the degree programme was a week-long residential placement in a religious community. While it has evolved in a number of ways, partly to accommodate larger student numbers, and has been located in different contexts, reflecting changing modes of delivery, the placement remains foundational to the experiential approach towards religion that continues to characterize Study of Religions at Bath Spa University. Placements in religious communities allow students to encounter religion ‘as it is lived’ in all its complexity and diversity, requiring them to apply ethnographic techniques learnt in the classroom and to conduct themselves as professional researchers. Learning in and assessment of fieldwork placements thus develops skills identified in the Subject Benchmark Statement for Theology and Religious Studies; including ‘empathy and imaginative insight’, ‘capacity for reflexive learning’, ‘ability to attend to others and have respect for others’ views’, ‘ability to gather, evaluate and synthesise different sorts of information’, ‘analytical ability and the capacity to formulate questions and solve problems’ and ‘presentation skills, both oral and written’. Experiential learning is critical to Theology and Religious Studies. However evocative and vivid a description, nothing can replace immersion in religious communities for gaining an understanding of life within a tradition. More than this, encounter may be personally transformative, going beyond information-gathering to fostering genuine respect for and understanding of an alternative life-world. In turn, experiential learning involves examining the student’s own beliefs and values and thus directly contributes to their personal development and, through the skills acquired, to their career aspirations. The intense nature of fieldwork and the richness of the experience, also means that assessment requires especial care if it is to value reflexivity alongside data capture and interpretation. Consequently, marking criteria need to reflect the complexities of the learning activities undertaken through a placement, and embody a variety of learning outcomes related to the combination of attitudes, skills and knowledge. Building on an earlier placement-related bid (FDTL 5 2004) involving the Subject Centre and the Universities of Chester and York St John, the decision to apply for Tranche 9 Mini-Project funding was motivated by an awareness that the issues we had previously identified had yet fully to be addressed. We were concerned to improve the fieldwork placement for our own students, curious about what other departments were offering in terms of experiential learning and hopeful that good practice could be shared. Accordingly, our main project aim was to facilitate fieldwork placements in Theology and Religious Studies by producing a website containing research and resources, and encouraging dialogue between religious communities, tutors and students. Working outwards from the Study of Religions team’s expertise in providing fieldwork placements and assessing student work based on these placements, further forms of experiential learning were identified and included in the project (i.e. day visits, study visits abroad and vocational placements). 2. Initial Project Planning: Aims and Processes The aim of this project, as stated in our bid, was to improve learning and assessment in Theology and Religious Studies by exploiting the potential of fieldwork placements. In more detail, we aimed to: Survey experiential elements in TRS departments in the UK to identify good practice and forge a dedicated learning community; Extend opportunities for fieldwork placements and improve the quality of the experience for students and host communities; Facilitate a variety of types of fieldwork placements in TRS departments through providing open educational resources; and Encourage dialogue between religious communities, lecturers, teachers and students about religion as lived experience. In broad terms, other than the initial survey, the main focus of the project was to be the creation of a website. In order to achieve these aims, we established an Advisory Group comprising: Dr Lynn Foulston, Programme Leader for Religious Studies, University of Wales, Newport; Prof. Paul Hyland, Head of Learning and Teaching at Bath Spa University; Dr Richard Noake, Head of Theology and Religious Studies, University of York St John; and Dr Simon Smith, Subject Centre. This membership ensured a balance of expertise that reinforced the emphasis on learning and assessment, complemented the focus on placements at Bath 2 Spa University (both in terms of different forms of placements and a variety of forms of experiential learning) and drew upon relevant project management skills. This Group was planned to meet twice to provide detailed feedback and critical evaluation of the project as well as establishing priorities for future development. 3. Chronological Overview Initially, the project was to begin in July 2009 and to be completed by June 2010. However, due to a combination of factors, especially the commissioning of the project team to produce a research report, identifying faith communities in Bath and North-East Somerset and how best the Local Authority could engage with them, it was necessary to request an extension for a further academic year. This was discussed with the Advisory Group who, like us, recognized the possible value of this report for the Living Religion project itself. Consequently, the milestones had to be revised to accommodate the additional workload and to schedule the planned activities until June 2011. For initial and revised schedules with comment, see Appendices A and B. 4. Activities The main project activities included the following. 4.1 Survey of Theology and Religious Studies Departments A questionnaire (see Appendix C) was designed and distributed to discover where fieldwork placements in particular and experiential elements in general were provided. Departments were identified by consulting the AUDTRS Handbook published by the Subject Centre, supplemented by checking University websites for recent changes. A total of 40 questionnaires were sent to Departments in Great Britain (efforts to contact HEIs in Northern Ireland proved fruitless), yielding 19 responses. 4.2 Creation of Website The major deliverable of the project is the website. There was significant delay in website design and development. However, in 2010-2011 Gavin Wilshen has taken responsibility for this and during the year has built the website in consultation with the project team. 4.3 Community Visits and Interviews A programme of visits was scheduled in order to ascertain the views and any concerns of communities that hosted placements for Bath Spa students. This was important because feedback from communities had been very limited and generally confined to negative experiences. The goal was to involve the communities in improving the quality 3 of placements from the perspective of students and communities alike, and on that basis to seek to extend opportunities for placements. These visits included local placement providers (extremely important for those students with caring roles who are unable to undertake residential placements) alongside placement providers in other parts of Britain. Similarly, care was taken to include placement providers associated with different forms of religion and spirituality. These visits featured an interview with a member of the community charged with placements and a risk assessment as well as the collection of visual materials. To date seven visits have been made, of which one was a three-day stay undertaken in an effort to reproduce the student experience insofar as possible. 4.4 Development of Community Profiles The role of Community Profiles is to provide guidance on communities for visitors. As well as being useful to our own students, these are intended to assist lecturers and teachers in planning fieldwork for their students. They are also intended to help communities by making clear for which groups they could cater and on what basis. Following advice from the Advisory Group, a template was designed to elicit key information about the communities including the community's affiliation, purpose, facilities, requirements and suitability for guests (see Appendix E). This was then emailed to communities with whom we have built relationships (23 in total). Five communities did not complete templates, three did but limited their availability to Bath Spa students by refusing permission for their details to be uploaded to the project website, with 15 communities giving permission to upload their details. As a result of project activities, two new organizations provided profiles with permission to upload to the website. 4.5 Student Focus Groups and Questionnaires Part of the project was to gain a more detailed understanding of the student perspective on the placement experience than gained through the normal processes of module evaluation. It was also decided to investigate the value for students of day visits to places of worship though these do not feature on the website. Focus groups were convened by Prof. Paul Hyland for the smaller groups of students undertaking placements in 2008-2009 and 2009-2010 supplemented by a further focus group and short questionnaires for a subsequent cohort. Students’ responses were acquired in order to inform other aspects of the project where students’ needs for guidance could be addressed. 4 4.6 Generating Good Practice Guides The survey of Theology and Religious Studies Departments revealed the need for documentation on aspects of placements and other forms of experiential learning that would make it easier to extend the provision. As well as developing a number of documents ourselves, we requested documentation and visual materials from other Universities involved in experiential learning activities. 4.7 Researching the History of Placements at Bath Spa University The history of the University and particularly Religious Studies at Bath Spa was researched to contextualize the placement and to emphasize its role in pedagogy for over 35 years. As part of this, Donald Whittle, a pioneer of the subject and of the placement, was interviewed. 5. Deliverables 5.1 Report on Survey of Theology and Religious Studies Departments Of the 19 responses, 14 indicated that the Departments offered experiential learning defined as elements where students engage directly with religious practitioners in their own settings. This bias towards experiential learning may not be representative of the sector in that departments involved in this form of learning would perhaps have been more likely to complete the questionnaire. Nevertheless, Departments that did not offer experiential learning but did complete the questionnaire indicated a range of relevant practical and pedagogical factors informing current practice and inhibiting the inclusion of experiential elements. Practical issues included the availability of staff, shortage of time, the costs involved and access to religious communities as well as the problems posed by different study modes, notably distance learning, and large classes. Pedagogical issues mentioned included current staff expertise and suitable means of assessment. Accordingly, where appropriate, Departments suggested that additional staffing, more time, financial support and links with religious communities would enable them to offer experiential learning as would the appointment of qualified staff and guidance on how to integrate experiential elements into the curriculum. Departments that did offer experiential learning did so in a variety of ways, the most common of which was the day visit to religious centres and places of worship such as synagogues, churches, mosques, temples, monasteries and gurdwaras but also Pagan and New Age sites. A number of Departments arranged for study visits abroad with students travelling to India, Korea and Egypt as part of their programmes. 5 Placements also featured in a number of programmes. Vocational placements often occurred in theological contexts involving work in pastoral settings, for example, youth work and ministerial training. Other vocational placements related to Religious Education and schools. Fieldwork placements could be associated with research projects and dissertations and might involve concentrated study on/in a specific community or sustained study of/in a specific locality. It was noteworthy that none of the Departments (including Bath Spa) that did offer experiential learning had a specific policy on this aspect of their provision. The project has addressed some of the issues raised by Departments that did not offer experiential learning either directly, by disseminating information and guidance to make it easier to offer experiential learning (for example, Community Profiles and Good Practice Guides including Framework for Policy on Experiential Elements, see 5.2 and 5.6 below), or indirectly, by assisting Departments to make the case for experiential learning as a priority that merits institutional investment (for example, the Skills Audit, see 5.6.ii below). However, subsequent to the survey discussions at conferences and meetings revealed that courses and modules with a Religious Studies element including experiential learning may be found outwith Theology and Religious Studies Departments and thus their practice was not captured by the survey, for instance BA (Hons) Religion and Education based in Early Years, Education and Teaching at the University of Huddersfield. This lack of visibility is becoming more common as Universities restructure and retrench. 5.2 Features of Website The ‘Living Religion’ website containing the other deliverables itemised below can be found at http://www.livingreligion.co.uk. The main sections of the website are as follows: Home Introduction to project About Us Introduction to team and history of placements at Bath Spa Community Profiles Information on communities together with visual and video material Research Report on questionnaire responses Final project report Links to articles arising out of the project To include relevant research from other scholars Resources 6 Good practice guides on a variety of topics such as research ethics, quality assurance and enhancement, tips for students and assessment ideas supplemented by examples of good practice from other Universities Student Work To include samples of student projects on placements once cleared To include student work from other Universities Contact Us Contact details for the team How Can I Get Involved? Interactive section for lecturers, religious communities and students to ensure currency and expand scope of website Day Visits Examples of past visits Study Visits Abroad Examples of past visits Schools Useful links to Sacred Space projects from ‘Learning Outside the Classroom’ and ‘reonline’ Links Useful links to other projects and websites 5.3 Summary of Results of Community Visits and Interviews For most of the communities, hosting students reflected the mission of the organisation, whether this was expressed as an educational mission, a mission to serve others, a spiritual mission, or a mission of ‘spiritual education’. It was felt that hosting students was an appropriate and valuable contribution to make, and that it was good that the resources available were being used, and that students could see a religious community/place of worship in action. Some groups felt that association with a university gave credibility to the academic and educational side of their work. Several welcomed the challenging nature of the questions asked by students, which prompted reflection on the part of the community. One community admitted that the donations came in handy. All felt that the objectives of the placement were clearly spelt out, and more recently recruited hosts said that personal conversations with the tutor had enabled them to understand the university’s intended outcomes. However, several wished to know more about the individual students further in advance. It was suggested that students could provide a CV, information about skills they could offer the community, why they chose the particular placement, and what they hoped to gain from the experience. Most were very positive about the experience of having students on placement and found the vast majority of students to be respectful of community values and customs. They enjoyed helping students, for example, ‘enabling students to overcome their fears of unknown and unfamiliar traditions’. However, it could also be hard work, as briefing 7 and debriefing students about their experiences could be time-consuming. Students vary considerably in the way they approach the experience, in terms of clarity of objectives, independence and initiative, and they also have very varied interests. All felt that it was an extremely valuable experience for students. It shakes up their preconceptions, and takes them ‘out of their comfort zone’. They have experience of community life, and of living in a spiritual community, which may include silence, prayer/meditation, and an environment free from mobile phones, computers, and the media. They are enabled to understand what it means to be committed to a religious path, and are able to meet a wide range of practitioners, from different backgrounds and with different levels of commitment. Sometimes they can share insiders’ experiences of outsiders’ reactions, if involved in outreach to the wider community, such as distributing food with ISKCON. The experience can be personally transformative as well as intellectually enlightening. Students may have access to resource materials for study unavailable elsewhere. They may also have the opportunity to develop useful ‘skills for life and work’ such as balancing their needs with appreciating the other demands on a host’s time, taking the initiative and asking appropriate questions, problem solving and practical skills, and (sometimes) working closely and intensely with a small group, whether other students or hosts. Students are encouraged to offer practical help as part of the way the university recompenses the community for their kindness in accommodating students. Hosts acknowledged that students did indeed assist with tasks such as decorating, gardening, washing up, office tasks such as filing, librarian tasks such as reclassifying items, project planning and events management, distributing publicity materials, and working in the community’s shop. However, it was felt that this practical help was not so important and should not be allowed to dominate. Students also helped the host communities by giving them insights into how others see them, and especially how younger people react to the site. Students’ questions were welcomed as ‘it is a useful learning experience for practitioners to have to explain themselves to outsiders’. Students could offer more to the community if their skills and interests were known further in advance. IT skills, such as website design, would be welcomed, as would any expertise in areas such as vegetarian cooking or construction work. Students could consider returning to the community as volunteers. The university procedures for booking students placements can present difficulties, though it was not easy to see how to resolve these. Timing of placements could be difficult for some communities. Problem behaviour from students could include students going off site, wearing inappropriate clothes, forgetting to use permissions letters for research, being rather passive, and failing to write thank you letters or give community any feedback. However, such problems were rare and some communities said there were no problems. Some communities prefer students on their own and others in small groups. Financial arrangements need to be clear. 8 A common suggestion for improving the placement experience was that communities would like to know more about the students, further in advance. If communities were aware of students’ skills, and of their particular research interests, more assistance could be given. Communities also wanted more feedback, both from individual students and the university, after the placements are completed. Some communities felt that students would benefit from more briefing/reading about the particular community in advance. Placements could be times to coincide with festival and important events. Students need to be prepared for bad weather, and to understand the notion of sacred space. All interviewees would encourage other communities to offer placements to students. However, they would advise being very clear about boundaries and explaining rules clearly. They agreed that providing placements is hugely beneficial and breaks down barriers. Suggestions for preparatory reading were given, but rarely academic sources. Some recommended only their website, and others considered that coming with an open mind and heart was more important than background reading. Some interesting and important issues arising from visits and interviews turned on the differences between outsider and insider perspectives on community identities, the balance between taking the initiative and not monopolising hosts’ time, and the balance between preparedness and open-mindedness. A community may be perceived as Pagan or Hindu where its self-perception is as a form of universal spirituality. A student may struggle to complete the research without being assertive in approaching informants but equally by being too demanding of them. A department may want students to be well prepared through background reading but it is vital to reassert the value for students of experiencing the community in such a manner that any preconceptions that will colour their interpretations can be challenged as well as confirmed. In summary, the following are ways in which the communities consider that that placement experiences could be enhanced: i. Students should contact communities further in advance, with their CVs and details of their skills, interests, and objectives. ii. Students should consider returning to perform volunteer work in placement communities. iii. Students should always send thank you letters, and feedback to communities. If appropriate, they may send copies of their assignments. iv. Departments should explore ways of providing more feedback to communities, through evaluation and student work. v. Departments should provide reading lists on each community (see Community Profiles on website). vi. Departments should develop further links with communities, for example, as visiting speakers, ‘employer’ partners, volunteering opportunities. 9 For questions, see Appendix D. 5.4 Analysis of Community Profiles 17 Community Profiles are available online though we are actively seeking additions. Reading through the Community Profiles, a number of issues emerge. One major issue is the affiliation of the community in the sense of it being unique or part of a wider network and, where associated with a major tradition, whether and in what ways it may be deemed representative. Related to this, communities may differ in their openness to visitors who do not share their faith commitment. Notwithstanding, all communities have values and rules that may differ from the secular norm and students’ own lifestyles. Consequently, communities have requirements about diet and mealtimes, dress, alcohol and tobacco, and sexual activity. They have requirements about attendance at services and sometimes the performance of work. A whole range of practical matters also need to be considered. These include attitudes to technology (that is, whether visitors may use mobile telephones or connect to the internet) and, more basically, whether this is possible due to sometimes remote locations. In some cases, it is not possible to watch a television or listen to the radio. Standards of accommodation and its suitability differ with particular implications for disabled access. In some locations, warm clothing, wellington boots and workwear may be required. Further areas of sensitivity surround views about money. Some communities refuse to accept direct payment and creative ways of making donations have to be found. Other communities may be businesses and fully integrated into the mainstream economy. Additionally, visitors need to be made aware of the possible presence and backgrounds of other clients or visitors to the community, who may not share the values of the community, or, where the community is involved in outreach to disadvantaged sectors of society, may have serious problems. 5.5 Summary of Results from Student Focus Groups and Questionnaires Some of the main ideas that emerged from Student Focus Groups concerned the role of placements in a Religious Studies programme, the challenges they pose and the possible controversies to which they give rise. In explaining why a placement should be an integral part of a Religious Studies degree, students were in agreement that it was a vital element of their learning that enabled them to gain real insights into other people’s spiritualities. Through participant-observation they could find out what they could not discover from attending lectures or reading books. They also noted that this was an opportunity to try out theories and methods for themselves. Crucially, they could discover how religious communities conduct their daily lives. Necessarily, this also involves interaction with people from different backgrounds which was seen as a useful skill for life and work. Overall, the placement was believed to make a significant 10 contribution towards personal and professional development, including some unexpected outcomes such as learning to meditate. On return from placement, there was much informal discussion of students’ experiences that was regarded as reflecting the importance attached to the placement. Among the challenges that students identified were coping with ‘culture shock’, balancing aspects of participation and observation of community life and worship, maintaining an open mind and questioning one’s own values without conceding one’s personal integrity and, more generally, working independently and managing a project in a new context. At times, interpersonal dynamics (whether between small groups of students or between students and their hosts) proved difficult. Moreover, students sometimes found the task of interpretation daunting, not least in respect of determining how far a specific community might be representative of a wider tradition. Students were aware that their presence might materially affect the way in which the community presented itself or might provoke negative reactions. They understood that there might be a clash of values and that their participation in religious activities might be misconstrued as tokenistic or as demonstrating adherence. Many of these points are inevitable aspects of ethnographic research. However, Student Focus Groups indicated the need for resources such as Tips for Students and the practical components of the Community Profiles. Further, students’ responses indicated that a specific evaluation form was needed for placements rather than relying on a more generic module evaluation form (see 5.6 below). Some of the main ideas that emerged from questionnaires concerned the value of the placement as a learning experience. The vast majority of students considered the placement to be the most important part of the course. Comments included ‘an amazing and completely worthwhile experience – I’ve never been anywhere so peaceful’, ‘the strangest experience of my life but one of the most valuable’ and ‘I loved it and learned a lot’. Several students felt that they had learned so much that it was impossible to describe. However, their learning ranged from deep theological reflections on the nature of the Godhead and personal spiritual experiences to acquiring new domestic and culinary skills and the practical implications of simple living. For example, ‘I learned that the Hare Krishnas believe in one God … not unlike my own personal beliefs’, ‘I had some quite strong spiritual experiences in the Chalice Well garden which I had not expected’, another student commented that s/he was now proficient in ‘cooking tofu and seaweed [and] repairing a hoover’ while yet another discovered ‘I could cope in a very different environment with only basic amenities’. Students learned about the religious communities in a variety of ways: interviews and informal conversations; observing and participating in rituals and ceremonies; access to books and resources not generally available; and auditing talks to other groups. Other opportunities for learning about the communities were afforded by interactions with the wider society that enabled outsider perspectives to be obtained. These perspectives 11 often revealed the important role played by the community in the locality as providers of services. Notwithstanding previous academic study, the students did report having been surprised in some respects, underlining the importance of an ethnographic approach. This was true even when they might have been expected not to be surprised, for instance in the dependence of Buddhist monks upon the laity or the presence of multifaith imagery in a Hindu setting, but the placement made this real in a qualitatively different manner. Beyond this, students were surprised by the diversity within communities, their own emotional reactions and the openness of members of communities to discuss deeply personal issues. Nevertheless, students reported some tensions in terms of their level of participation and their experience of deference, hierarchy and gender roles in the communities. It is striking that, whereas one student discovered s/he could meditate, another discovered s/he could not. In addition to the evidence of the effectiveness of placement learning, this feedback reinforced the importance of evaluating the placement as a discrete item but also led us to develop an equivalent evaluation form for the communities to complete (see Appendices F and G; see also 5.6 below). 5.6 Good Practice Guides for Website The website includes a section on Resources that contains sub-sections: i. ii. iii. iv. v. Policy (Framework for a Policy on Experiential Elements plus a Sample Policy) This was developed as the Survey showed that this was lacking in all Departments. Audit of Skills This was developed in order to indicate the value of experiential learning in achieving both Subject Benchmarking objectives and Employability skills. This was mainly aimed at University staff who might need to make a case for experiential elements in the curriculum but has also proved useful to students in identifying how their studies relate to their future careers. Assessment for Learning This was developed to propose a number of ways in which fieldwork placements could be assessed. This addressed a concern of respondents to the Survey. Quality Assurance and Enhancement (Protocol for Focus Groups and Questionnaires for Communities and Students) These methods of evaluation were found to be helpful in the course of the project as means of exploring in more depth the value and demands for all those involved in the placement. Research Ethics (Risk Assessment plus Sample Form; Data Protection plus Sample Permissions Letter and Form) 12 vi. vii. This was developed to assist both lecturers and students with ethical and legal dimensions of engaging in research with human participants. Tips for Students This was developed in response to student requests for a ‘briefing paper’ or ‘dummy guide’ especially on practical aspects of a placement. Good Practice Guides from other Universities Documentation from other Universities has been included both to provide a number of options on key features of providing experiential learning opportunities and to extend the range of those opportunities by exemplifying and illustrating additional possibilities. These are arranged under the headings of Resources for Study Visits Abroad, Resources for Day Visits and Resources for Fieldwork. 5.7 The History of Placements at Bath Spa University A short history of the University and of Religious Studies at Bath Spa was written, demonstrating the foundational role of the placement in programmes since the mid1970s. An edited form of the interview with Donald Whittle examines why the placement was introduced and how the student body has changed over the decades. 6. Dissemination A number of opportunities for dissemination occurred in the course of the project. Two of these were conferences organized by the Subject Centre, ‘Courting Controversy’ (July 2010) and ‘Teaching Religions of South Asian Origin’ (January 2011). At the former in a paper entitled ‘Do they really believe that? Experiential Learning outside the Theology and Religious Studies Classroom’, we reported on our findings in relation to the literature on experiential learning and as a case study in the realities of cultural and religious diversity on the ground (see Discourse, vol. 10, no. 1). At the latter in a keynote address entitled ‘ When the twain meet: Redefining “British” Religions through Student Encounters with Religious Communities’, we challenged the applicability of the concept of ‘diaspora’ in the light of the history and membership of religions of South Asian origin. Here the fieldwork placements were cited as evidence that these religions are now rooted in British soil and often have British converts (see Discourse, vol. 10, no. 2). Another opportunity was the Glastonbury Academic Symposium (April 2011) that brought together scholars from a number of universities and members of the local community involved in serving the diverse spiritual seekers drawn to Glastonbury. The goal was to facilitate academic study of Glastonbury as a spiritual phenomenon. Denise Cush was invited to the Symposium to talk about how the University uses Glastonbury placements and visits (see Chalice Well Trust, Isle of Avalon Foundation, Library of Avalon and Pilgrim Reception Centre under Community Profiles on the website), and what we have learned from the project about what makes for a successful experience. The Symposium led to further offers of possible placements which has increased the number of Community Profiles on the website. 13 Two further conference papers are planned for July 2011. One, at the annual conference of AULRE (the Association of University Lecturers in Religion and Education) at Glasgow University, will publicize the project to an audience of teacher educators and researchers in religious education. We will also be giving a paper on the links between placements and employability called ‘Does Religious Studies Work? Employability and Experiential Learning’ at ‘Foundations for the Future’, organized by the Subject Centre. The main means of dissemination of project deliverables is the Living Religion website. 7. Evaluation As recognised by the Advisory Group and reflected in our Interim Report, the initial project proposal was rather ambitious. However, we have achieved the majority of the planned project outcomes. The main section of the website which remains to be developed is the section with sample student work. The problems facing us are obtaining permissions from students and communities, and ensuring that the work does not breach copyright rules. Some progress has been made on this but student work will not be available online by the official end of the project. The original plan was for the project to produce materials that would facilitate visits by schoolchildren and their teachers to religious communities and places of worship as well as involving teachers with the project. In the course of the project, we discovered that materials for schools had already been provided by two other projects, ‘Learning outside the Classroom’ and ‘reonline’. Thus our website section for schools gives links to these projects as well as a locally developed example. In any case, the Community Profiles contain information relevant to schools and sometimes feature the same communities used in the other projects. Discussions with teachers have occurred at intervals during the life of the project and education professionals will be involved in its evaluation once the website is online. Conference papers have led to potential links with a new project led by Lynne Scholefield and Stephen Gregg on field trips and study tours which has obvious synergy with this project. In addition, conference papers have led to discussions with colleagues across the sector about experiential learning in the subject. The project has had impact in at least three ways to date. For the team, it has led to improvements in our own practice such as preparing a policy on experiential elements and changing how the placement is evaluated and by whom. It has also enhanced our understanding of both students’ and communities’ perspectives on the placement experience as well as deepening our appreciation of the role and importance of experiential learning in a variety of forms. 14 Better understanding of students’ perspectives has enabled us to meet their needs by, for example, providing Community Profiles containing practical information, ‘Tips for Students’ and more generally by reviewing support materials. Better understanding of communities’ perspectives has informed the creation of evaluation forms by which communities can communicate any feedback. On the whole, relationships have become closer and, in addition, further communities have offered placements. Once the website is online, we will invite comment from our Advisory Group, Theology and Religious Studies lecturers, school teachers and, perhaps most importantly, students and religious communities. In May 2012 we will evaluate use of the website in terms of the number of hits and whether it has given rise to new contacts. We also plan to re-contact respondents to the initial survey for their evaluation of the resource, especially those with an interest in experiential elements. 8. Continuity The project will continue after the end of the funded period both to complete the sections of the original plan that we have not been able to deliver and to ensure that the website remains current. The motivation for this is in part that we will be using the website as a resource for our own students on a regular basis. Once the website goes online, it is our hope that colleagues in Theology and Religious Studies Departments and members of religious communities will respond to our How Can I Get Involved? section of the website and enable us to continue to add new materials that we can be included under Resources and further Community Profiles. In order to achieve this, it will be necessary to publicize the website which we plan to do through professional associations and academic conferences. For example, in addition to the July 2011 conference papers cited in 6 above, the website will be announced at the conference of the Association of Religious Education Inspectors, Advisers and Consultants and in the Religious Education Council of England and Wales’ newsletter. 9. Conclusion This project has already made some contribution towards facilitating fieldwork placements though its true success can only be assessed in the longer term. However, it has confirmed our belief that fieldwork placements are particularly valuable to Theology and Religious Studies. Among the reasons for this are the following: 15 An opportunity for students to apply methodology for themselves and to rethink theoretical frameworks in the light of their experience. For example, a student in a focus group commented that s/he had ‘a far better understanding of the research methods stuff you read about’. The implications of this were discussed in our papers on experiential learning and redefining ‘British’ religions (see 6 above). A means for students to enhance their subject skills, especially in relation to understanding and representing the convictions and behaviours of others. For instance, a student explained that the placement was ‘[a]n unforgettable experience that allows you to discover first-hand exactly what a particular religious group believe. A great chance to meet new people, while challenging yourself and your misconceptions!' The role of fieldwork placements in developing subject skills is documented in our Audit of Skills (see 5.6.ii above). A means for students to enhance their employability skills, and more generally promote their personal development, perhaps most crucially in the areas of interpersonal sensitivity, tolerance of stressful situations, and independence and self-management. One student said the placement ‘helps you develop the personal skills of how to work and interact with different cultures.’ The role of fieldwork placements in developing employability and personal skills is documented in our Audit of Skills (see 5.6.ii above). An effective form of experiential learning that facilitates rich and deep learning which is holistic and contextualized. A typical student response is ‘I felt that I learned more about [this] religion than I would ever have picked up from lectures and books’. This was the main focus of our paper on experiential learning (see 6 above). A flexible element of a student programme that can be delivered in a variety of modes. This is not the case at Bath Spa University in terms of the one-week fieldwork placement but placements can feature in project modules and dissertations and occur in vacations and non-timetabled spaces. An opportunity for students to engage with the wider community and for religious groups and organizations to interact with both younger people and the academic study of religions. In addition, specific students may forge longer-term relationships with these groups and organizations without becoming adherents. An attractive feature of a Theology and Religious Studies programme that assists with recruitment and marketing. On this subject, we give one of our current students the last word: 'the placement went above and beyond my expectations and it was one of the most fantastic learning opportunities that I have ever had. When I chose to come to Bath Spa University, I made my decision partly because I was enthralled at the prospect of being able to go and live with a religious community. To me, this sounded utterly awesome. My time with The Community of the Many Names of God was truly unforgettable and I was right to make this a deciding factor when I accepted my offer to study here.' 16 Appendix A Original Schedule with Comment Date July 2009 October 2009 November 2009 December 2009 January 2010 February 2010 March 2010 April 2010 May 2010 June 2010 Project Activity Set up Advisory Group; liaise with communities Send out survey; set up contacts and visits; produce preliminary designs for website; first meeting of advisory group Set up student focus groups; produce support materials for students Analyse survey data Prepare and pilot skills audit Identify case studies Visits to religious communities Draft good practice guides and test with students and communities Finalise good practice guides; Second meeting of advisory group Complete report Project Deliverable Launch website pages Upload support materials onto website Upload skills audit into website Upload case studies onto website Upload community profiles onto website Upload good practice guides onto website Upload report onto website 17 Comment Advisory group set up; limited liaison with communities Survey piloted in September after consultation with Subject Centre. revised in light of suggestions from Advisory Group and then sent out to 40 Departments; contact list updates and first visits planned; section of University website reserved for project website; first meeting of advisory group held 29 th October Additionally, interview with Donald Whittle Student focus groups set up; some support materials prepared Additionally, visit to Bath Spa University by Dr Richard Noake Survey data analysed; no progress on website Additionally, student focus groups convened; first community visits Skills audit prepared; no progress on website Additionally, interim report submitted Project suspended Project suspended Project suspended One community visit conducted Project suspended Second meeting of advisory group held 29th April See revised schedule Appendix B Revised Schedule with Comment Date June 2010 Project Activity Prepare conference paper July 2010 Initiate creation of website, finalising personnel and process (including legal disclaimer) Further community visits Design community profile template to be sent to existing and new host communities as part of annual placement programme Start to collect samples of student work from 2009-2010 cohort September 2010 Further community visits Finish framework for policy Add framing narrative to audit of skills October 2010 Identify other project materials for website (including memorandum of agreement, risk assessments, etc.) Explore links with school sector (including Sacred Space project, SACRE and local schools) Request examples of student work from other Universities Project Deliverable Present paper at Courting Controversy Conference (8/9 July) Site architecture and design established Comment Paper delivered at ‘Courting Controversy’ Conference Additionally, revised for and accepted by Discourse Case studies of host communities Community profiles available online (autumn term) Student work available online (autumn term) Case studies of host communities Policy framework available online Audit of skills available online Upload other project materials to website Three further community visits conducted; materials from case studies incorporated into community profiles Community profile template agreed and sent out; profiles collated and made available internally only for student use Provide links where appropriate Not actioned Student work available online (autumn term) Not actioned 18 Creation of website initiated and website designer identified along with initial ideas for website Not actioned Not actioned Framework for policy finished and provided for website Framing narrative added and provided for website Other project materials identified and provided for website Date November 2010 December 2010 Project Activity Visits to other universities and further contributions invited Start to prepare top tips and troubleshooting sections Write guidance on terminology January 2011 Work on assessment guidance Focus on externalities and ‘real-world settings’ February 2011 Final meeting of Advisory Group Integrate school materials March 2011 April 2011 May 2011 Write summary document for website and publishing Write summary document for website and publishing Report and accounts June 2011 Prepare conference paper Project Deliverable Upload further materials to website Complete first draft of top tips and trouble-shooting sections Guidance available online Assessment guidance available online Ideas for and examples of engagement with local government, not-for-profit organisations and other employers available online Meeting held Any further materials uploaded Comment No visits; further contributions invited; new documents provided for website Guidance for students and staff prepared Additionally, one further community visit; open meeting with students returning from placements Considered unnecessary Not actioned Not actioned Additionally, keynote speakers at ‘Teaching Religions of South Asian Origin’, paper revised for and accepted by Discourse; participation in networking event for project holders Abandoned due to cost constraints Not actioned Good practice guides available on website (once live) as a collective download Summary document completed Report and accounts to Subject Centre Present paper at HEA-PRS conference 19 As above Additionally, presentation at Glastonbury Academic Symposium Paper accepted for ‘Foundations for the Future’ Conference July 2011 Appendix C Questionnaire for Survey of Theology and Religious Studies Departments QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. Living Religion: Facilitating Fieldwork Placements in Theology and Religious Studies We have received funding for this project from the Higher Education Academy Subject Centre for Philosophical & Religious Studies. This project aims to improve learning and assessment in Theology and Religious Studies (TRS) by exploiting the potential of fieldwork placements and to develop sustainable relationships between the academy, religious communities and schools. As part of this project we are surveying TRS departments to discover where fieldwork placements and, more generally, experiential elements are provided. By experiential we mean elements where students engage directly with religious practitioners in their own settings. The results of this survey will be publicised along with exemplars of good practice on-line on the project website. We would be very grateful for your help in completing this questionnaire and hope that you will be interested in participating in the project activities. Please return the completed questionnaire as soon as possible and not later than November 30th 2009. Data Protection Published survey data will be anonymised as far as possible and no references to individual Departments/Subjects made without permission. Any examples of good practice mentioned in the report or published on the website will of course be credited. By returning this questionnaire you are giving permission for the project team to use the data supplied. You retain the right to withdraw from the research at any time and any data supplied will be destroyed. Prof. Denise Cush and Dr Catherine Robinson d.cush@bathspa.ac.uk; c.robinson@bathspa.ac.uk Department of Humanities School of Humanities and Cultural Industries Bath Spa University 1. Name of University …………………………………………………………….. 2. Name of Department/Subject …………………………………………………………….. 20 3. Does your Department offer experiential learning? Yes/No (please delete as appropriate). If yes, go to 4 below. If no, go to 9 below. 4. If yes, what form does this take? (please tick as appropriate) a. Visiting places of worship and religious communities b. Fieldwork placements e.g. residential research c. Extended study visits abroad d. Vocational placements e.g. ministerial and pastoral work e. Other (please specify) …………………………………………………….. …………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 5. Please provide further details, e.g. compulsory or optional for students, year of study in which it features, number of students involved, relationship to assessment, contribution to subject and other skills, extent of staff involvement and role of external personnel. Occurrence 1 Occurrence 2 Occurrence 3 Occurrence 4 Type of activity Compulsory or optional Year of study Number of students Assessment Subject and other skills Staff involvement External personnel Other (please specify) 6. Why does the Department include experiential elements? ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 21 7. Does the Department have examples of good practice that it would be willing to share, for example student handbooks, guidance for host communities, innovative assessment, case studies? Yes/No (please delete as appropriate). If yes, go to 8 below. If no, go to 9 below. 8. Please provide a brief description of any examples. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9. Would the Department be interested in participating in project activities? Yes/No (please delete as appropriate). 10. Name and role of person completing this form and contact details for correspondence with the project team. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Please return by email to c.robinson@bathspa.ac.uk or by post to Catherine Robinson, Department of Humanities, School of Humanities and Cultural Industries, Bath Spa University, Newton Park, Newton St Loe, Bath, BA2 9BN. 22 Appendix D Interview Questions for Members of Host Communities 1. Why did you agree to take our students on placement? 2. Did you get sufficient guidance from us about the placement? 3. How have you found the experience of having Bath students on placement? 4. What do you think students gain from the experience? 5. Has having the students been of any benefit to you? 6. Could having students potentially benefit your community? 7. What problems, practical or otherwise, have presented themselves? 8. How would you improve the placement experience? 9. Any advice you would give a community thinking of offering a placement? 10. Any background reading you would recommend for a student coming on placement with you? 23 Appendix E Community Profile Template Name of Community: Address: Website: Contact Details: Contact person: Contact email: Telephone: Fax: Affiliation/tradition: Brief description of purpose of community: Facilities for visitors/guests: Any disability access or other issues of which visitors/guests need to be aware: Requirements for visitors/guests: Practical tips for visitors guests: Suitable for visits from: Recommended preparatory/background reading: Public liability insurance: Permission to upload these details to our website: Primary schools/secondary schools/university students (please delete) yes/no (please delete) yes/no (please delete) 24 Appendix F Placement Questionnaire for Students Name of Student: ……………………………………………………………………………………………………. Placement Community/Centre: …………………………………………………………………………….. Were you adequately prepared for your placement? What opportunities did you have to find out about the beliefs and practices of the community/centre? Were you able to make a contribution to the community/centre? What did you learn from your placement? Did anything surprise or impress you? Did anything offend or distress you? What advice would you give to another student going to this community/centre? Any further comments? 25 Appendix G Placement Questionnaire for Communities Name of Person Completing Form: …………………………………………………………………………….. Placement Community/Centre: …………………………………………………………………………….. Were you adequately briefed about the placement? Were you adequately briefed about the students coming on the placement? What opportunities did students have to find out about the beliefs and practices of your community/centre? Were students able to make a contribution to your community/centre? What did students learn from their placements? Did anything surprise or impress you? Did anything offend or distress you? What advice would you give to another community/centre considering whether to offer a placement? Any further comments? 26 27