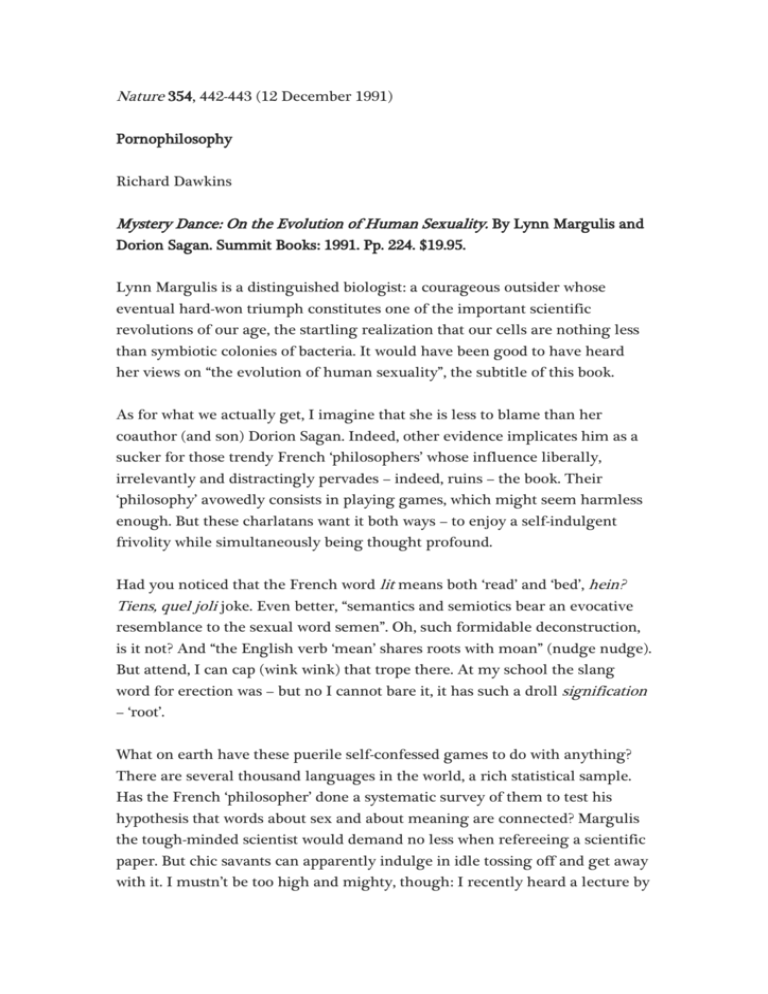

Pornophilosophy - Richard Dawkins

advertisement

Nature 354, 442-443 (12 December 1991) Pornophilosophy Richard Dawkins Mystery Dance: On the Evolution of Human Sexuality. By Lynn Margulis and Dorion Sagan. Summit Books: 1991. Pp. 224. $19.95. Lynn Margulis is a distinguished biologist: a courageous outsider whose eventual hard-won triumph constitutes one of the important scientific revolutions of our age, the startling realization that our cells are nothing less than symbiotic colonies of bacteria. It would have been good to have heard her views on “the evolution of human sexuality”, the subtitle of this book. As for what we actually get, I imagine that she is less to blame than her coauthor (and son) Dorion Sagan. Indeed, other evidence implicates him as a sucker for those trendy French ‘philosophers’ whose influence liberally, irrelevantly and distractingly pervades – indeed, ruins – the book. Their ‘philosophy’ avowedly consists in playing games, which might seem harmless enough. But these charlatans want it both ways – to enjoy a self-indulgent frivolity while simultaneously being thought profound. Had you noticed that the French word lit means both ‘read’ and ‘bed’, hein? Tiens, quel joli joke. Even better, “semantics and semiotics bear an evocative resemblance to the sexual word semen”. Oh, such formidable deconstruction, is it not? And “the English verb ‘mean’ shares roots with moan” (nudge nudge). But attend, I can cap (wink wink) that trope there. At my school the slang word for erection was – but no I cannot bare it, it has such a droll signification – ‘root’. What on earth have these puerile self-confessed games to do with anything? There are several thousand languages in the world, a rich statistical sample. Has the French ‘philosopher’ done a systematic survey of them to test his hypothesis that words about sex and about meaning are connected? Margulis the tough-minded scientist would demand no less when refereeing a scientific paper. But chic savants can apparently indulge in idle tossing off and get away with it. I mustn’t be too high and mighty, though: I recently heard a lecture by an Oxford disciple of this school of modish French dippiness, and it took me a full five minutes to see through him (it was when he made his big point about Jesus’s name and Jacques Derrida’s both beginning with J). The philosophical priorities in this book can be gauged from the authors’ bizarre estimation of Heidegger as “perhaps the most influential philosopher of the twentieth century”. He was the old Nazi, you remember, who singlehandedly wrestled with the problem of ‘being’. Without Heidegger it would have escaped us that “The nothing annihilates itself”. Even Lacan (a favourite among Margulis and Sagan’s French mentors) refers to Heidegger’s “dustbin style in which currently, by use of his ready-made mental jetsam, one excuses oneself from any real thought”. The book is built around a recurring theme of striptease. The androgynous stripper peels off garment after garment, metaphorically revealing our evolutionary past. S/he is forever twiddling round and changing sex – sorry, “gender” – on successive gyrations of the mystery dance. At times the language suggests a cack-handed attempt at eroticism. Or it may seek to embarrass, in which case it succeeds: As she climaxes a man briefly appears beneath her, existing only long enough to ejaculate before disappearing again into her shuddering loins [apologies to W. B. Yeats not offered]. In retrospect the audience realized that they saw her give ejaculatory virtual birth to a full-grown male. The body turned and below the rippling abdomen of the seven-veiled striptease artist was an obscure pubis, dark and hairy. The erect penis, the unmistakable signal of his sex, shrunk on the next rotation. It became the clitoris [pp. 59-60]. Yuck! But there’s more: She lustily stands spreadeagle. Slowly she turns and bends to expose her dark buttocks and the wet genitals below, bidding him welcome [p. 60]. These passages are chosen more or less at random. The pages drip with similar ‘pornophilosophy’, a genre which, I understand, originated with Sartre. Personally, if I must have porn, I prefer it shorn of pretension. One cannot help feeling that if Desmond Morris had written that paragraph (he wouldn’t) he’d be noisily accused of flagrant, pot-boiling sensationalism. Should this book get away with it just because of who Lynn Margulis is? Actually, although it has a joyless earnestness where Morris has a teasing sense of fun, Mystery Dance in one way approaches The Naked Ape – the 2 same charmingly cavalier lack of evidence for the same daringly speculative functional explanations. In some cases literally the same explanations, albeit unacknowledged. Margulis and Sagan attribute one of their theories of the female orgasm to an unpublished correspondent, a businessman inspired by a conversation with a sexually boastful US airman. In fact, as I told the same businessman when he wrote to me some years ago, an identical theory was clearly set out in The Naked Ape (distributed around the world in a mere 12 million copies). Meanwhile, back at the dance, more and more veils are lasciviously removed until we expose the ancestral bacteria. Ah, you think, now Margulis must have something worthwhile to say. But no. With a deft gyration of the intellect, our scientific authoress rotates herself into her literary alter ego and, by the time he has given vent to another stupefying salvo of continental obscurantism, the moment has passed: But there is perhaps a deeper phase, the metaphysical plane of pure phenomena, continuous appearances. The evolutionary stripper is a curious creature: the G-string is not a thin cloth decorated with tassels but rather a word, a letter, a musical symbol for ultimate nakedness [honestly, I’m not making this up]. Paradoxically, when the G-string is removed – to the accompaniment of strange vibratory music consisting in part of a silent triangle and a gentle crash of cymbals – the nakedness is gone. S(he) stands before us as fully dressed as ever before [p. 27]. What on earth, you may say, is all this about? Well, wait: We encounter our sexual ancestors along the slippery slope of signs and signifiers, via the medium of language. The use of signs of any kind necessarily obscures; words represent or replace signified things in absentia; they are little black masks. We postpone reality to discuss it; without this postponement, this instantaneous replacement of our sexual ancestors, or things in general, by their signs there could be no possibility of language, of signification at all [p. 28]. And then where would we be? How a scientist of Margulis’s calibre and rigour can be gulled by this pretentious drivel is as far beyond comprehension as the prose itself. Let us be charitable and hope that she had an argument with her coauthor and lost. But if, rightly, you value Lynn Margulis and her reputation, do her a favour and ignore this book. 3 Richard Dawkins is in the Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK. 4