read Newman as a philosopher

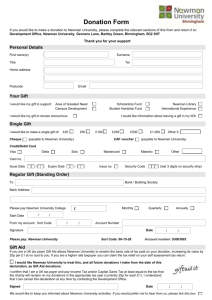

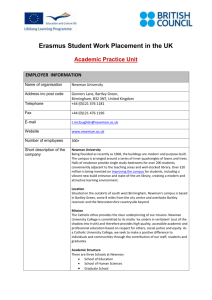

advertisement

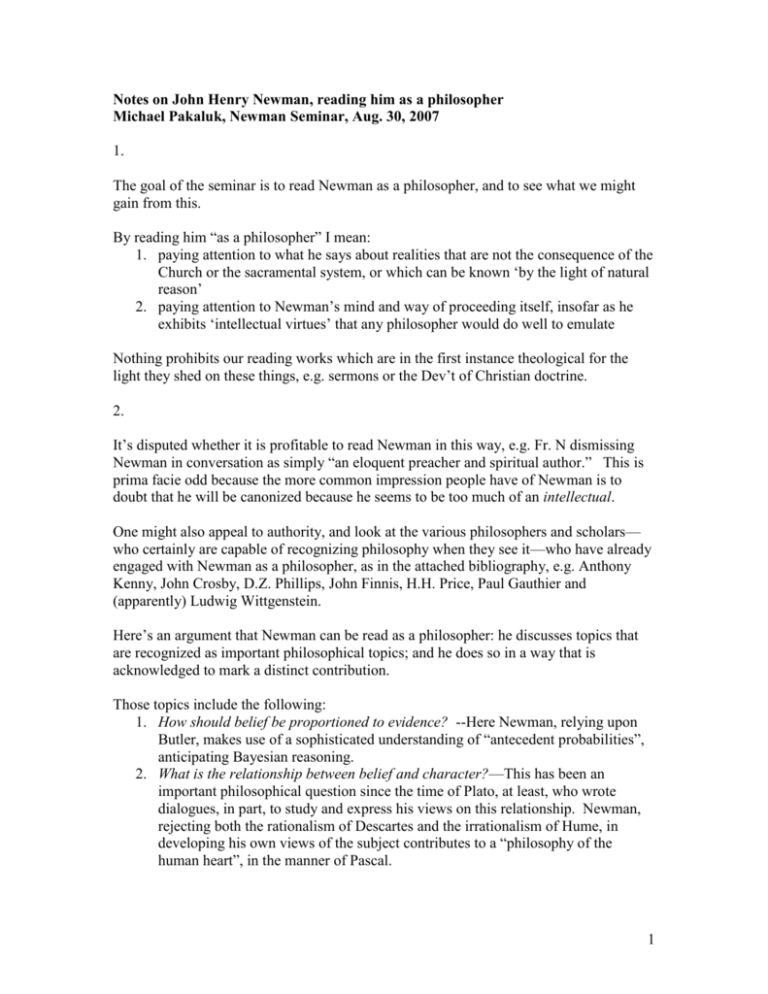

Notes on John Henry Newman, reading him as a philosopher Michael Pakaluk, Newman Seminar, Aug. 30, 2007 1. The goal of the seminar is to read Newman as a philosopher, and to see what we might gain from this. By reading him “as a philosopher” I mean: 1. paying attention to what he says about realities that are not the consequence of the Church or the sacramental system, or which can be known ‘by the light of natural reason’ 2. paying attention to Newman’s mind and way of proceeding itself, insofar as he exhibits ‘intellectual virtues’ that any philosopher would do well to emulate Nothing prohibits our reading works which are in the first instance theological for the light they shed on these things, e.g. sermons or the Dev’t of Christian doctrine. 2. It’s disputed whether it is profitable to read Newman in this way, e.g. Fr. N dismissing Newman in conversation as simply “an eloquent preacher and spiritual author.” This is prima facie odd because the more common impression people have of Newman is to doubt that he will be canonized because he seems to be too much of an intellectual. One might also appeal to authority, and look at the various philosophers and scholars— who certainly are capable of recognizing philosophy when they see it—who have already engaged with Newman as a philosopher, as in the attached bibliography, e.g. Anthony Kenny, John Crosby, D.Z. Phillips, John Finnis, H.H. Price, Paul Gauthier and (apparently) Ludwig Wittgenstein. Here’s an argument that Newman can be read as a philosopher: he discusses topics that are recognized as important philosophical topics; and he does so in a way that is acknowledged to mark a distinct contribution. Those topics include the following: 1. How should belief be proportioned to evidence? --Here Newman, relying upon Butler, makes use of a sophisticated understanding of “antecedent probabilities”, anticipating Bayesian reasoning. 2. What is the relationship between belief and character?—This has been an important philosophical question since the time of Plato, at least, who wrote dialogues, in part, to study and express his views on this relationship. Newman, rejecting both the rationalism of Descartes and the irrationalism of Hume, in developing his own views of the subject contributes to a “philosophy of the human heart”, in the manner of Pascal. 1 3. To what extent are our beliefs voluntary?—This is the so-called question of the “ethics of belief”. For Newman, it is important that our religious beliefs be “up to us”, because of his emphasis on the importance of finding and adhering to the right doctrines in religion. (He describes the opposite view as ‘liberalism’ and, in his bigletto speech, describes his life as devoted to combating it. See Text 1 below.) 4. How does it affect our thinking, that we are persons in relation to other persons?—This too is an anti-Cartesian aspect of Newman, and has been recognized as an anticipation of both ‘personalism’ and Wittgenstein. Newman works out a view according to which thinking is always inherently social. 5. How are out beliefs related to our experience? --Newman accepts the basic thesis of empiricism, that “all knowledge is first in the senses”, but he construes experience (‘the senses’) broadly and with sophistication, and he avoids any Kantian suggestion that the mind constructs or contributes to experience. 6. What is the relationship between faith and reason? –This is of course a classic philosophical problem, because there is a task of describing the relationship that belongs to philosophy too. Newman is recognized as perhaps that one thinker (even more than Aquinas) who has the most sophisticated and perceptive things to say about this subject. 7. Education. What is the purpose of education? What is the distinct character of higher education? What is the nature of a university community? What are the distinct intellectual virtues which education should develop?—Philosophy of education is classically an important part of education, and Newman, as the founder of a university, says things about this which are of fundamental importance. 8. Certainty—What is certainty? How does it differ from knowledge? How can we be certain of things that we accept only indirectly, on the authority of someone (and ‘by faith’)? – It has been claimed that Newman’s views here anticipate Wittgenstein and were influential for Wittgenstein. 9. Understanding—What is it to grasp (understand) something? Can we grasp things in degrees? How can it be reasonable to assent to what we do not fully grasp? 10. What is the most cogent argument for God’s existence? – Newman believed it was the “argument from conscience”, and that the traditional proofs, although valid, were useless in the modern world to inspire conviction or devotion. Another way to approach this is as regards Newman’s relation to the Cartesian tradition of philosophy. The marks of that tradition are: 1. Foundationalism: knowledge requires a foundation and is built up from that 2. Intellectual autonomy: this project starts with the thinking subject alone 3. Quest for certainty: its goal requires the attainment of inescapable certainty 4. The attempt to verify what counts as the sound (correct) operation of the mind: a part of the project is confirming the conditions under which the mind is a reliable instrument for arriving at truth 2 In Newman one finds a thinker who has the sensibilities of a British empiricist (viz. concerned with our actual experience and psychological processes; somewhat pragmatic and aiming at preserving ‘common sense’), but who at the same time rejects each of these marks. He rejects them—feeling their force—and does not simply ignore or dismiss them. He does so in the late 19th, with a sophistication that is not seen in the main tradition of philosophy until J.L. Austin and Wittgenstein in the mid- to late- 20th century. Given the above, it becomes a problem to explain why Newman is sometimes not regarded as a philosopher, and for this there are at least six reasons: 1. His limited influence. As a matter of fact, Newman has proved so far to have been lacking in influence in philosophy. This is to some extent an artifact of how people are educated; but also it is the result of the attractiveness of modes of philosophy which are appealing because they hold out the prospect of progress, like science (Russell, Husserl). (Note: We need to ask whether Newman’s lack of influence among philosophers is justified or accidental. E.g. Reid is relatively without influence, but that implies a criticism of philosopher, not Reid.) 2. A literary, not formal, ideal of rigor. Newman is rigorous, but with precision of speech rather than with the technical rigor that involves defining terms and formalizing arguments. 3. His forensic style of argumentation. Newman’s method of reasoning is forensic (‘inductive’) rather than in the manner of a demonstration; so he seems to be arguing ad hominem rather than offering universally valid results. Moreover, except for his argument for the existence of God from conscience, he seems to formulate no distinctive arguments, which can be attributed to him. 4. His lack of care for architectonic or reflection on what he is doing. Newman is rarely concerned to tell us what he is doing; he simply does it. 5. His subordination of philosophy to theology. Newman definitely views philosophy as a handmaiden to theology and is concerned for philosophical truth only insofar as it contributes to theology. 6. His ‘therapeutic’ contribution. We are used, when reading Austin and Wittgenstein, to recognizing that the main point of reading him is for us to change in how we see things (to acquire better intellectual habits), so that, as W. said, the result is that we no longer wish to raise certain kinds of questions (and we recognize that it is sound and healthy that we don’t; and we have some skill in pointing out incoherencies in those who do). But perhaps because of Newman’s context, we do not use the same standard in evaluating him. From these considerations it follows that some useful goals in reading Newman would be the following: 1. To introduce as much rigor and formalism as is appropriate, given the subject matter that he is discussing. (And, following Aristotle, we might think that frequently this will be very little formal rigor at all.) 3 2. To aim to be as reflexive as possible in appreciating his work, i.e. to get clearer than even he was about what precisely he is arguing for, i.e. what are its components and implications. 3. To identify exactly how Newman criticizes and rejects the Cartesian tradition, and to try to formulate in what respects his contribution is distinctive. Text 1 “To one great mischief I have from the first opposed myself. For thirty, forty, fifty years, I have resisted to the best of my power the spirit of liberalism in religion. Never did Holy Church need champions against it more sorely than now, when, alas, it is an error overspreading as a snare the whole earth. … “Liberalism in religion is the doctrine that there is no positive truth in religion, but that one creed is as good as another. It is inconsistent with any recognition of any religion as true. It teaches that all are to be tolerated, for all are matters of opinion. Revealed religion is not a truth, but a sentiment and a taste, and it is the right of each individual to make it say just what strikes his fancy.” 4