The Reflective Access Requirement is to be

advertisement

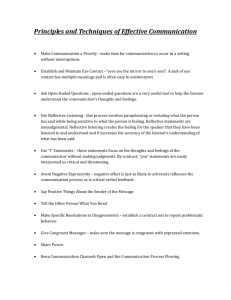

Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 CHAPTER TWO Rationality, Reflective Access and Epistemic Responsibility 1. Introduction The Phenomenality Constraint articulates the existence of a metaphysically necessary connection between rationality and phenomenal consciousness. But one might ask, why is there any such connection? Doesn’t the very existence of such a connection stand in need of some kind of philosophical explanation? If we understand this question as asking for a reductive explanation of the connection between rationality and phenomenal consciousness in terms of more fundamental metaphysically necessary truths, then my response is that I see no reason to suppose any such explanation can be given. I doubt that there is any explanation of the connection between rationality and phenomenal consciousness that does not presuppose it in some way. However, this does not mean that there is no way to achieve a reflective understanding of the existence of the connection between rationality and phenomenal consciousness. Let us assume that there exists a connection of the relevant kind between rationality and phenomenal consciousness in the proposed manner – why then do we care about rationality? Why is it important for us to carve things up in this way? What role is played in our cognitive lives by the notion of rationality that could not equally be played by some externalist replacement notion – schmrationality – which does not bear the proposed connection with phenomenal consciousness?1 My strategy for responding to this challenge makes essential appeal to the Reflective Access Requirement. I begin by discussing the formulation of the requirement, 1 This challenge was pressed on me forcefully by Jerry Fodor, in conversation. 1 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 distinguishing a weak version, which is plausible, from a strong version, which is not. Next, I argue that this weak version of the Reflective Access Requirement is best explained by appeal to the Phenomenality Constraint. If this is right, then any argument in support of the weak version of the Reflective Access Requirement will also serve as an argument in support of the Phenomenality Constraint. I go on to argue that there is a commitment to the truth of the Reflective Access Requirement in our intuitive conception of epistemic responsibility in reflective critical reasoning, which is central to our conception of ourselves as persons. This line of argument is intended to provide an indirect source of theoretical motivation for the Phenomenality Constraint, supplementing the more intuitively-based motivations given in the previous chapter. It is also intended to provide an explanation of the wider theoretical significance of the intuitions that support the Phenomenality Constraint by explaining why we should care about a notion of rationality that elicits those intuitions. The overall aim is to show that the Phenomenality Constraint plays a crucial and pivotal role in making sense of important features of our cognitive lives. 2. Formulating the Reflective Access Requirement Let us begin with the following initial formulation of the Reflective Access Requirement: The Reflective Access Requirement (RAR): necessarily, what it is rational for a subject to believe is accessible to the subject on the basis of reflection alone. This formulation needs some unpacking. First, I will take it that access is a cognitive matter – accessing what it is rational to believe involves forming a higher-order belief 2 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 about what it is rational to believe.2 Hence, there is a distinction between accessing the reason-giving states that make it rational to form a certain belief, which is a cognitive matter, and the availability of those states to phenomenal consciousness, which is not.3 Moreover, access cannot just be the result of a lucky guess: the higher-order belief must be knowledgeable, or at least both rational and true.4 A further issue, to be addressed in due course, concerns the modal strength of the notion of accessibility in terms of which the requirement is formulated. Finally, the notion of reflection is to be understood broadly, so as to include not only a priori reasoning, but also introspection of one’s current psychological states and introspective memory of one’s past psychological states. The Reflective Access Requirement is to be distinguished from a stronger claim that is endorsed by some internalists, which I call the Guidance-by-Access Requirement:5 The Guidance-by-Access Requirement (GAR): necessarily, a belief is rational only if it is formed on the basis of access to what it is rational for the subject to believe. This claim requires that what it is rational for the subject to believe is not merely accessible, but is actually accessed, by the subject. Moreover, it requires that any belief must be formed on the basis of such access if it is to be rational. It is therefore a consequence of the Guidance-by-Access Requirement that the notion of access enters into the constitutive account of what makes it the case that a belief is rational. The 2 Brewer (1995, 1999) proposes a contrasting, non-reflective version of the access requirement, according to which reason-giving states themselves must embody some kind of appreciation of their own reasongiving significance. See Ch.5 for further discussion. 3 In saying this, I reject a higher-order thought theory of phenomenal consciousness, for reasons mentioned briefly in Ch.1 and below. 4 Williamson’s (2000) anti-luminosity argument introduces complications, discussed briefly below. 5 A reflective version of the Guidance-by-Access Requirement is endorsed by Bonjour (1985) where it plays a role in his argument against foundationalism (Ch.2); a non-reflective version is endorsed by Brewer (1995, 1999) and deployed in his (1999, Ch.5) argument for conceptualism about the content of perceptual experience. Both versions of the requirement are discussed, and ultimately rejected, in Ch.5. 3 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 Reflective Access Requirement, by contrast, allows for a sharp distinction between the constitution and the accessibility of the rational status of a belief. The higher-order accessibility of the rationality of a belief need not be any part of what constitutes the rationality of the belief. Indeed, the Reflective Access Requirement is best construed as a constraint of adequacy on a constitutive account of what makes it the case that a belief is rational. Such an account should be logically prior to the Reflective Access Requirement and should explain why it is true. In order to see how this explanatory constraint might be satisfied, we first need to distinguish between two readings of the strength of the modal notion of accessibility in terms of which the Reflective Access Requirement is formulated. According to weak readings, what is required is accessibility in principle; whereas on strong readings, what is required is accessibility in practice. This is, in effect, a distinction between two accounts of what grounds the possibility of the subject’s access to what it is rational for him to believe. According to strong readings, the possibility of access is grounded in the reflective capacities of rational subjects. In other words, rational subjects must possess the reflective capacities that make it possible in practice for them to access what it is rational to believe. Strong readings of the requirement therefore rule out the possibility of unreflective rationality – that is, rationality in the absence of any capacity for reflection on what it is rational to believe. This consequence seems extremely implausible. Surely, there can be unreflective creatures who are capable of making rational inferential and perceptual transitions even though they are not sufficiently reflective to be capable of thinking about the rational credentials of those transitions. Indeed, it seems that many animals and children are in 4 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 precisely this position.6 Of course, one might insist on a “high” conception of rationality that is incompatible with these intuitions.7 However, there are theoretical considerations against adopting such a demanding conception of rationality. For example, if there are rational constraints on the possession of certain concepts, then the strong version of the Reflective Access Requirement implies that unreflective creatures are incapable of possessing those concepts. Consider the observational and demonstrative concepts that figure in basic perceptual beliefs: it is very plausible that a thinker possesses such concepts only if he is disposed to apply them rationally in forming basic perceptual beliefs on the basis of perceptual experience. The strong version of the Reflective Access Requirement implies that creatures cannot possess such concepts and use them in forming basic perceptual beliefs unless they are also capable of self-ascribing the perceptual experiences on which such beliefs are based and conceptualizing them as states which provide reasons for the beliefs in question. Thus, it rules out a plausible model of our reflective capacities as an “overlay” on more basic conceptual capacities that we share with unreflective creatures. Why should we accept the overlay model of our reflective capacities?8 The answer is that it is supported by explanatory considerations – in particular, it provides for a plausible explanation of the ontogenetic and phylogenetic development of the reflective 6 See Gopnik and Graf (1988) for evidence that three-year old children often know things without knowing how they know them. 7 Compare Bonjour (1980, p.66): “Any non-externalist account of empirical knowledge that has any plausibility will impose standards for justification which very many beliefs that seem commonsensically to be cases of knowledge fail to meet in any full and explicit fashion. And thus on such a view, such beliefs will not strictly speaking be instances of adequate justification and knowledge. But it does not follow that externalism must be correct. This would follow only with the addition of the premise that the judgements of common sense in this area are sacrosanct, that any departure from them is enough to demonstrate that a theory of knowledge is inadequate.” 8 This “overlay” model is challenged by Bermudez (2003) and Millar (2004). Similar issues are at play in McDowell’s (1994, p.64) denial of the claim that our perceptual experiences have a nonconceptual content which can be shared by the perceptual experiences of creatures that do not possess any concepts. 5 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 capacities in question. If unreflective creatures can share the concepts possessed by reflective creatures, then they can also draw on these conceptual resources in coming to acquire the reflective capacities in question. For instance, they can redeploy the concepts employed in basic perceptual beliefs in self-ascribing the perceptual experiences on which those beliefs are based. On such an account, the capacity for reflecting on the rationality of perceptual beliefs depends asymmetrically on more basic capacities for forming perceptual beliefs rationally, but unreflectively. By contrast, the strong version of the Reflective Access Requirement rules out the possibility of any common conceptual basis which might be drawn on in making the developmental transition from not having the relevant reflective capacities to having them. In effect, it forces us to explain the transition not in terms of conceptual enrichment, but rather in terms of conceptual change. Of course, it is ultimately an empirical question which of these explanations is correct. As a point of philosophical methodology, though, we should prefer a theory of concepts and rationality which leaves such questions open, rather than forcing us to abandon independently plausible explanatory hypotheses. On these grounds, the strong version of the Reflective Access Requirement should be rejected. This leaves us with the weak reading of the requirement – but how exactly is it to be understood? In particular, how are we to understand the notion of accessibility in principle? I propose that we can gloss this as follows: what it is rational for the subject to believe is accessible in principle just in case it would be accessible in practice, given idealizations of the subject’s reflective capacities, but holding fixed the reason-giving states that determine what it is rational for him to believe. So, for example, consider a child or an animal with no reflective capacities at all: if we hold fixed the reason-giving 6 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 states that determine what it is rational for him to believe, and idealize on his capacities for bringing those states into phenomenal consciousness and reflecting on their reasongiving significance, then he will be able to access what it is rational for him to believe on the basis of reflection alone. The relevant notion of idealization is not simply “whatever it takes” since we are to hold fixed the states that determine what it is rational for the subject to believe. Nor is there any danger of trivializing the Reflective Access Requirement, since it is not the case that all facts are made accessible to a subject merely by idealizing his capacities for reflection alone.9 On a weak version of the Reflective Access Requirement, what is supposed to ground the possibility of access, if not the reflective capacities of the subject? The alternative is that the possibility of access is understood to be grounded by the nature of the reason-giving states that determine what it is rational for the subject to believe. In other words, the constitutive account of what it is rational for the subject to believe is what explains why it is that the Reflective Access Requirement is true. I now want to argue that the Phenomenality Constraint plays an indispensable role in providing such an explanation. 3. Explaining the Reflective Access Requirement The explanation that I am proposing depends on getting right the relation between the phenomenal properties of states, in virtue of which they are available to phenomenal 9 It might be objected that the relevant kinds of idealization can affect what it is rational for the subject to believe. This is true, in that idealization on the subject’s reflective capacities can make it rational for him to form certain reflective beliefs that it would not have been rational for him to form otherwise (assuming that what it is rational for the subject to believe depends in part on his psychological capacities). However, it is also innocuous, so long as there are no cases in which what it is rational for the subject to believe prior to idealization is no longer rational after idealization. 7 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 consciousness, and the possibility of higher-order reflection on those states. Two points are crucial here. First, subjects can have phenomenally conscious states without engaging in any higher-order reflection on those states and without even having the capacity for any such reflection. Second, the phenomenal properties of phenomenally conscious states typically play a role in the causal explanation of exercises of higher-order reflection upon those states by subjects with the requisite reflective capacities. For these reasons, I claim that phenomenal properties are constitutively independent of higher-order reflection. However, there are limits on the possibility of error with respect to higher-order reflection on one’s own phenomenal properties. Whenever a subject forms a false belief about the phenomenal properties of his phenomenally conscious states, he is either less than fully attentive or less than fully rational.10 If we define “brute error” as error which cannot be explained in terms of deficiencies in either attention or rationality, then we can say that brute error is impossible with respect to higher-order reflection on the phenomenal properties of one’s own phenomenally conscious states. If a fully attentive and rational subject forms a belief that he is in a phenomenally conscious state with certain phenomenal properties, then he is; and if he forms a belief that he is not in a phenomenally conscious state with certain phenomenal properties, then he is not. Notice that there are no corresponding limits on the possibility of error in the perceptual case. Consider a fully attentive and rational subject who is forming beliefs about the external world on the basis of his perceptual experience, without reliance on any background beliefs. If he forms a belief that there is a dagger before him, it cannot be inferred that there is a dagger before him, since he may be hallucinating. Likewise, if he forms a belief As Williamson (2000, p.94) observes, “There is no limit to the extent to which we can be lured by fallacious reasoning and wishful thinking, charismatic gurus and cheap paperbacks.” 10 8 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 that there is no dagger before him, it cannot be inferred that there is no dagger before him, since his perceptual mechanisms may be malfunctioning, while leaving his rationality intact. What explains why brute error is impossible in the case of higher-order reflection on the phenomenal properties of one’s phenomenally conscious states? According to a judgement-dependent conception of phenomenal properties, a reflective judgement to the effect that one is in a state with certain phenomenal properties can make it true that one is in a state with those properties.11 But this line of explanation is ruled out by my claim that phenomenal properties are constitutively independent of higher-order reflection. The challenge, then, is to explain why there are distinctive limits on the possibility of brute error in the case of higher-order reflection, but without appealing to some kind of supermechanism that is just like the mechanisms involved in perception except that it never malfunctions.12 The crucial contrast between the perceptual case and the case of higher-order reflection is as follows. If the subject is fully attentive and rational, his reflective judgement about the phenomenal properties of his phenomenally conscious state is based on the phenomenally conscious state that it is about. The reflective judgement does not make it true that he is such a state, as the judgement-dependent conception proposes; rather, the reflective judgement is made true by the occurrence of the phenomenally conscious state on which it is rationally based. By contrast, no perceptual belief is made true by the occurrence of the perceptual experience on which it is based. Rather, a perceptual belief is made true by the fact that the world is the way it is represented as 11 12 See Wright (1989) for a version of the judgement-dependent conception. Martin (unpublished) presses this challenge. 9 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 being by the perceptual experience on which it is based. Hence, there is scope for brute error in the perceptual case because it is compatible with the subject’s rationality and attentiveness that his perceptual experience should fail to represent the world veridically. There is no analogous scope for brute error in the case of higher-order reflection. There is also a further, related difference between the perceptual and reflective cases. If a fully rational and attentive subject is having a perceptual experience which represents a dagger before him, he is not thereby in a position to form a rational perceptual belief that there is a dagger before him. This is because the perceptual experience only gives him a defeasible reason to believe that there is a dagger before him, which may be defeated by background beliefs to the effect that his perceptual experience fails to represent the world veridically. By contrast, if the subject is in a phenomenally conscious state with certain phenomenal properties, his reason for judging that he is in such a state is conclusive, in the sense that it suffices for the truth of his reflective judgement. There are no background beliefs that can defeat a reason of this kind, at least in the case of a fully rational and attentive subject. We can therefore conclude that, if a subject is in a phenomenally conscious state with certain phenomenal properties, then this puts him in a position, at least in principle, to form a rational belief that he is in such a state, on the basis of reflection alone. Moreover, given the impossibility of brute error, if the subject is fully attentive and rational, and does form the belief that he is in such a state on the basis of reflection alone, then his belief is true, since it is made true by the state on which it is rationally based. So, if a subject is in a phenomenally conscious state with certain phenomenal properties, then 10 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 this puts him in a position, at least in principle, to form a rational, true belief that he is in such a state, on the basis of reflection alone.13 We are now in a position to see how the Phenomenality Constraint explains the Reflective Access Requirement. The Phenomenality Constraint implies that, given a particular content-determining context, what it is rational for the subject to believe is determined by the phenomenal properties of his reason-giving states. Since his reasongiving states have phenomenal properties, it is in principle possible for the subject to bring those states into phenomenal consciousness. But, as we have seen, if a subject is in a phenomenally conscious state with certain phenomenal properties, then this puts him in a position, at least in principle, to form a rational, true belief that he is in such a state, on the basis of reflection alone. So, we can conclude: Necessarily, the phenomenal properties of a subject’s mental states are accessible to the subject on the basis of reflection alone. Moreover, it is plausible to claim that subjects are in a position, at least in principle, to determine the rational significance of being in a phenomenally conscious state with certain phenomenal properties on the basis of reflection alone.14 So, we can add: Necessarily, the reason-giving roles of the phenomenal properties of a subject’s mental states are accessible on the basis of reflection alone. I do not claim that any such condition is “luminous” in the sense that it puts the subject in a position to know that it obtains. Williamson (2000, Ch.4) has argued that no non-trivial conditions are luminous, by exploiting a tension between luminosity and a reliability requirement on knowledge. His argument is compatible with what I am claiming because rationality, unlike knowledge, is not subject to a reliability requirement, at least on the internalist conception I am developing here. 14 This need not require the subject to be in possession of a fully articulated philosophical theory of rationality. It is enough if he can exploit some intuitive grasp of the rational significance of being in phenomenally conscious states with the relevant phenomenal properties. 13 11 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 From these claims, we can infer that subjects are in a position, at least in principle, to form rational, true beliefs about what it is rational for them to believe on the basis of reflection alone. Or, in other words: Necessarily, what is rational for a subject to believe is accessible to the subject on the basis of reflection alone. This is exactly what is stated by the Reflective Access Requirement. The appeal to the Phenomenality Constraint is indispensable in the explanation of the Reflective Access Requirement. This is because only states that are available to phenomenal consciousness in virtue of their possession of phenomenal properties are rationally accessible on the basis of reflection alone. Of course, a pure reliabilist would deny this. He would claim that even deeply unconscious states, such as early visual states, would be rationally accessible to us by reflection alone if only we happened to possess a reliable method for forming reflective, higher-order thoughts about them. However, the case of the hyper-blindsighter, discussed in the previous chapter, demonstrates the intuitive inadequacy of this suggestion. The hyper-blindsighter has a reliable mechanism for forming reflective, higher-order thoughts about his phenomenally unconscious visual states on the basis of those very states, without mediation by inference or observation. Intuitively, however, these higher-order thoughts are no more rational than blind guesswork. Despite their reliability and the confidence with which they are delivered, they can be no more rational than mere guesses, because they are not based on any phenomenally conscious, or potentially conscious, reason-giving states. What the hyper-blindsight case reveals is that there are internalist constraints on the rationality of higher-order, reflective beliefs as well as first-order, unreflective beliefs. 12 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 And this just what we should expect. After all, the Reflective Access Requirement is itself formulated in terms of a notion of reflective access whose rationality is subject to internalist constraints. A condition of adequacy on any explanation of the Reflective Access Requirement is that it should explain why it is that we have internalist intuitions concerning the rationality of reflective access itself. Only an explanation that appeals to the Phenomenality Constraint can satisfy this condition. 4. Reflective Critical Reasoning and Epistemic Responsibility So far, I have been arguing that an appeal to the Phenomenality Constraint is indispensable for explaining the Reflective Access Requirement. But do we have any reason to suppose that the requirement is true? I want now to argue that we are committed to its truth by our intuitive conception of epistemic responsibility in reflective critical reasoning, which is central to our conception of ourselves as persons.15 In this way, I aim to show that an appeal to the Phenomenality Constraint is indispensable for making sense of deeply important features of our cognitive lives. Sophisticated thinkers engage in a practice of rational deliberation about what to believe and do. Rational deliberation involves thinking about what it would be rational to believe and do. This, in turn, involves reflecting on the rational credentials of one’s beliefs and other mental states and revising them accordingly – an activity that we may call “critical reasoning”.16 Fully reflective critical reasoning involves an ability to have 15 The argument draws at various points on the work of Tyler Burge, especially his (1996). I want to squarely acknowledge this debt, without presenting what follows as anything like an exegesis of Burge’s work. There are significant differences not only in the details, but also in the overall strategy. 16 Compare Burge (1996, p.246): “Critical reasoning is reasoning that involves an ability to recognize and effectively employ reasonable criticism or support for reasons and reasoning. It is reasoning guided by an appreciation, use, and assessment of reasons and reasoning as such. As a critical reasoner, one not only reasons. One recognizes reasons as reasons.” 13 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 higher-order thoughts about one’s own first-order attitudes. There also seems to be room for a more primitive form of critical reasoning which involves reasoning about evidential and logical relations between contents in the absence of any capacity for self-ascription of psychological attitudes.17 This more primitive form of critical reasoning requires some kind of systematic causal sensitivity to the differences between types of psychological attitudes that play different rational roles, but it does not require a capacity for conceptualizing those differences. Fully reflective critical reasoning, on the other hand, involves reasoning about relations between contents which are simultaneously conceptualized as the contents of certain types of psychological attitudes that the subject ascribes to himself. It is this more fully developed version of the capacity for critical reasoning that will be the focus of the discussion to follow. The point of engaging in critical reasoning is to contribute a positive epistemic status to one’s reasoning – namely, epistemic responsibility – by bringing it under one’s rational control.18 What it is to have this kind of rational self-control over one’s reasoning is to have, and be disposed to exercise, a capacity for revising or sustaining one’s beliefs appropriately in the light of one’s reflective scrutiny of their rational credentials.19 Epistemic responsibility may be regarded either as an epistemic obligation that binds sufficiently sophisticated thinkers or merely as a supererogatory epistemic value that only such thinkers can realize. Either way, it seems to be part of our commonsense conception of deliberation that any sufficiently sophisticated thinker can contribute this kind of 17 An account of this primitive analogue of critical reasoning, and its relation to the full-blown reflective version, is developed in Peacocke’s (1996) reply to Burge. 18 Burge (1996, p.258): “We are epistemically responsible only because we are capable of reviewing our reasons and reasoning. And we are paradigmatically responsible for our reasons when we check and review them in the course of critical reasoning.” 19 There is no commitment here to the kinds of doxastic voluntarism criticized by Alston (1988b). 14 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 positive epistemic status to his beliefs by engaging in reflective critical reasoning. Thus: necessarily, it is possible in principle for any sufficiently sophisticated thinker to contribute a positive epistemic status to his beliefs by engaging in reflective critical reasoning. But reflective critical reasoning can only contribute such a positive epistemic status if it is itself rational. So, necessarily, it is possible in principle for any sufficiently sophisticated thinker to engage in reflective critical reasoning in a way that is rational and hence to form rational beliefs about the rational status of his own beliefs. Burge presents an argument of this kind as a transcendental deduction of the existence of a rational entitlement to form introspective beliefs about our own psychological states.20 But it may equally well be regarded as a transcendental deduction of the existence of a rational entitlement to form beliefs about the rational status of our own psychological states. We are not yet in possession of an argument for the Reflective Access Requirement. After all, this requirement is formulated in terms of an epistemic restriction to reflection alone and the motivation for this restriction may be challenged.21 However, it seems to me that the motivation can be recovered from our conception of the nature of reflective critical reasoning. The crucial premise of the transcendental argument is that any sufficiently sophisticated thinker, whatever his contingent circumstances and state of information, can contribute a positive epistemic status to his beliefs by engaging in reflective critical reasoning. But then it must be possible for the thinker to do so merely on the basis of belief-forming methods such as introspection and a priori reflection, whose rational status does not depend on the thinker’s contingent circumstances or state Burge (1996, p.249): “If one’s judgements about one’s attitudes or inferences were not reasonable – if one had no epistemic entitlement to them – one’s reflection on one’s attitudes and their interrelations could add no rational element to the rationality of the whole process. But reflection does add a rational element to the reasonability of reasoning. It gives one some rational control over one’s reasoning.” 21 See Goldman (1999) and Williamson (forthcoming) for this challenge. 20 15 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 of information. Moreover, it is essential to the nature of critical reasoning that it can be exercised on itself reflexively, through potentially infinitely many iterations.22 So, once again, it must involve belief-forming methods such as introspection and a priori reflection, which can be exercised on themselves reflexively, through potentially infinitely many iterations. After all, you can reflect on your own reflections and introspect your own introspections, whereas you cannot, for instance, perceive your own perceptions. On these grounds, I conclude that the restriction to reflection alone is wellmotivated. We need one more step in order to complete the argument for the Reflective Access Requirement. It needs to be argued that, for any thinker, it is in principle possible on the basis of reflection alone to form beliefs about the rational status of his beliefs which are not merely rational, but also true. Why not suppose that these beliefs are subject to brute error in such a way that they can be fully rational and yet false? Why think they are relevantly different from perceptual beliefs, which can be affected by brute error on a global scale, as in the Brain-in-a-Vat case? I want to propose that the possibility of brute error in reflective critical reasoning is ruled out by our intuitive conception of the nature of epistemic responsibility. Thinkers who engage in reflective critical reasoning are epistemically responsible not merely for the process of rational reflection itself, but also for the beliefs they are reflecting upon. Moreover, they are responsible for those beliefs in an especially intimate way. As Burge puts the point, one is not responsible for one’s beliefs in the way that one Burge (1996, p.248) “Critical reasoning must be exercised on itself. Any critical reasoning…involves commitments by the reasoner. And genuinely critical reasoning involves an application of rational standards to those commitments. A being that assessed good and bad reasoning in others or in the abstract, but had no inclination to apply those standards to the commitments involved in those very assessments, would not be a critical reasoner.” 22 16 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 is responsible for something one owns or parents, such as a dog or a child.23 What is the cash value of this metaphor? Consider that if you are fully rational in believing that your dog would not foul the carpet, then you cannot legitimately be held responsible for the fact that your dog does foul the carpet. Your responsibility for the dog is constrained by the nature of your epistemic access to it, as well as by the nature of your control over it. But we do not conceive of a thinker’s epistemic responsibility for his own beliefs in the same way. We do not allow room for a case in which a thinker is fully rational in forming the reflective judgement that it is rational for him to believe that p, though that reflective judgement is false, so that he cannot be held responsible for forming an irrational belief that p. However, there will always be room for such a case unless we deny the possibility of brute errors in reflective critical reasoning. On the assumption that brute errors are possible, I might be fully rational in forming the reflective judgement that, all things considered, it is rational for me to believe that p, even though that reflective judgement is false. That is to say, I might be fully rational in believing that, all things considered, it is rational for me to believe that p, even though it would not in fact be rational, all things considered, for me to believe that p. So, if I were to go ahead and form the belief that p, my belief would be irrational. However, I could not legitimately be held responsible for this, since the irrationality of the belief would not be accessible from the perspective of my own reflective critical reasoning.24 Burge (1996, p.258): “The [simple observational] model implies that we are in reviewing our reasons only derivatively responsible for objects of review, as one might be responsible for the actions of one’s child or a dog…. But one is not epistemically responsible for the thoughts one reflects upon in critical reasoning the way one is responsible for something one owns or parents. One’s responsibility in reflecting on one’s thoughts is immediately for the whole point of view.” 24 Note that this view seems to be compatible with the point that reflective critical reasoning carries immediate rational implications for the reasoning that it concerns, a point which is plausibly essential to the unity of a person’s reflective point of view on the world (cf. Burge, 1996). Whenever I form a reflective judgement that, all-things considered, it is rational for me to believe that p, I thereby incur a rational 23 17 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 This completes the argument for the Reflective Access Requirement. If this line of argument is correct, then our conception of epistemic responsibility in reflective critical reasoning is to be explained in terms of the Reflective Access Requirement, rather than vice versa.25 We do not arrive at an adequate conception of epistemic responsibility by simply applying a generic conception of responsibility to the special case of reflective critical reasoning. Suppose, as a rough approximation, that we conceive of responsibility in general as a matter of doing all that can be reasonably expected in order to fulfill one’s obligations. Thus, one can be held responsible for failing to fulfill an obligation if one could be reasonably expected to fulfill it, but not otherwise. If we simply apply this general conception, then epistemic responsibility in reflective critical reasoning is merely a matter of doing all that can be reasonably expected of one in the task of reflecting on the rational credentials of your beliefs and revising them accordingly. Yet this does nothing to motivate the claim that the facts concerning what it is rational for a subject to believe are in principle accessible on the basis of reflection alone. At best, it motivates the claim that sufficiently reflective thinkers can be held responsible for failing to take into account those facts which are accessible on the basis of reflection, but cannot be held responsible for failing to take into account facts which are not so accessible.26 In short, the Reflective Access Requirement cannot be derived from a prior and independent notion of responsibility applied to the special case of reflective critical reasoning. Rather, commitment to believing that p. However, this cannot suffice to make it rational, all things considered, to believe that p, since otherwise I could bootstrap myself into the position of having a rational basis for believing that p, simply by forming an irrational reflective belief that I do. But even if my reflective belief is fully rational, it only suffices for the prima facie rationality of believing that p, on the current view. 25 This point becomes crucial for my discussion of the relationship between rationality and epistemic responsibility, below. Note that the main points about epistemic responsibility should generalize to the practical domain, at least with respect to our responsibility for our choices, as opposed to the causal consequences of those choices. 26 As Goldman (1999) observes, it also fails to make sense of the epistemic restriction to reflection alone. 18 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 a commitment to the Reflective Access Requirement is required in order to make sense of our conception of epistemic responsibility in reflective critical reasoning. I want to conclude this section by suggesting that our conception of epistemic responsibility in reflective critical reasoning is central to our conception of ourselves as persons. Persons are distinguished from other animals by the fact that they can legitimately be held responsible for their beliefs and actions. This is evidenced by the fact that we do not regard it as appropriate to adopt reactive attitudes, such as resentment, towards animals that are not persons. I do not mean by this to suggest that responsibility can be explained in terms of the appropriateness of adopting reactive attitudes – indeed, I take it that the correct direction of explanation is the other way around.27 Rather, the crucial point is that it is not appropriate to adopt reactive attitudes towards agents unless they are genuinely responsible for their beliefs and actions. Why should we suppose that only persons are genuine responsible for their beliefs and actions? The answer is that genuine responsibility requires a capacity for explicitly acknowledging what one is rationally committed to. In other words, it requires a capacity for critical reasoning – for recognizing one’s reasons as such. And it is plausible that persons are distinguished from other animals, at least in part, by virtue of their capacity for critical reasoning. Mere animals may be subject to the requirements of rationality and so they may be held to be irrational insofar as they fall short of satisfying those requirements. However, they cannot legitimately be held responsible for doing so since they are incapable of appreciating what it is that rationality requires of them. Another way to make the same point is that genuine responsibility requires a certain kind of freedom, where this is construed in terms of the capacity for responding to reasons as 27 See Strawson (1962) and Wallace (1994) for the opposing view. 19 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 such – that is, for choosing between alternatives on the basis of explicit consideration of the reasons weighing in favour of each side.28 Animals may be capable of action, but persons are distinguished by their capacity for acting freely on the basis of exercising a capacity for the relevant kind of free choice. Likewise, animals may be capable of rational belief-formation, but persons are distinguished by their capacity for critical judgement – they are able to decide what to believe on the basis of explicit consideration of what it would be rational to believe. The suggestion, then, is that epistemic responsibility requires a capacity for critical reasoning, which, in turn, is essential to personhood. Notice, however, that we began by distinguishing a fully reflective version of the capacity for critical reasoning, which requires conceptual self-consciousness, from a more primitive version, which does not. Although it was the fully reflective version of the capacity for critical reasoning that figured in the argument for the Reflective Access Requirement, I do not mean to commit myself to the claim that this version of the capacity is a prerequisite for epistemic responsibility, and hence for personhood. It is certainly not obvious that creatures capable only of more primitive forms of critical reasoning, in the absence of a capacity for conceptual self-consciousness, are unable to realize any degree of personhood or epistemic responsibility. However, insofar as these are concepts which do seem to admit of degree, this need not undermine the current line of argument that the internalist conception of rationality is central to our conceptual scheme. It will be enough to maintain that the fully reflective version of the capacity for critical reasoning enables a Susan Wolf (1990, p.94) says that, “…the freedom necessary for responsibility consists in the ability (or freedom) to do the right thing for the right reasons.” I am suggesting that the freedom necessary for responsibility requires more – namely, the ability to do the right thing on the basis of recognizing the right reasons as such. Similar remarks apply with respect to McDowell’s (1994) discussion of the Kantian notion of spontaneity, in particular his claim that “the space of reasons is the realm of freedom” (p.5). 28 20 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 more fully realized degree of epistemic responsibility, and hence personhood, by providing the conceptual resources for explicitly acknowledging one’s rational commitments as one’s own.29 5. Rationality and Epistemic Responsibility I have been proposing a broadly transcendental argument for the Reflective Access Requirement. According to this argument, we must be committed to its truth in order to make sense of our conception of epistemic responsibility in reflective critical reasoning. However, it is one thing to argue that the Reflective Access Requirement must be true in order to make sense of our conception of epistemic responsibility; it is another thing to explain what makes it true. We need to distinguish sharply between transcendental and explanatory arguments for the Reflective Access Requirement.30 The function of the transcendental argument is principally to explain why we care about the notion of rationality, by articulating its pivotal role in our conceptual scheme. The function of the explanatory argument, by contrast, is to articulate the way in which the rationality of a belief must be constituted so as to play this role. In other words, we need to appeal to a constitutive account of the rationality of a belief in order to explain why the Reflective Access Requirement is true. I have argued that an appeal to the Phenomenality Constraint is indispensable for meeting this explanatory demand. 29 See Burge (1998) for a more detailed development of this point. This distinction is not clearly drawn in Burge’s work. He claims that the source of our a priori rational entitlement to introspective self-ascription is its role in the reflective critical reasoning whose existence it makes possible. However, it seems plausible to object, as Peacocke does, that, “an entitlement to selfknowledge is one of the sources of critical reasoning, rather than vice versa” (1996, p.128). In my view, Burge’s transcendental argument plausibly establishes the existence of an a priori entitlement to introspective self-knowledge, but it does not explain the source of that entitlement. 30 21 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 The notion of epistemic responsibility has figured only in the transcendental argument for the Reflective Access Requirement, but not in the explanatory argument. I have not appealed to the notion of epistemic responsibility in explaining what makes it the case that a belief is rational. I do not claim, for instance, that what makes a belief rational is that it is such as to be taken up into an epistemically responsible practice of reflective critical reasoning. This would surely be to reverse the correct direction of explanation. For one thing, we need an independent grip on what it is for a belief to be “such as to be” taken up into such a practice. For another thing, we need the kind of grip on that notion in terms of which we can make sense of our conception of epistemic responsibility in reflective critical reasoning. What I have argued is that our conception of epistemic responsibility is informed by a more fundamental, and distinctively internalist, conception of rationality. It seems to me that if we reverse the correct direction of explanation here, then we will fail to provide a satisfactory account of the relationship between rationality and epistemic responsibility. Classical internalism, as proposed by Bonjour (1985) and criticized by Goldman (1999), proceeds along the following lines. First, a broadly deontological conception of rationality is proposed, according to which epistemic responsibility is a requirement for rationality.31 Second, the Reflective Access Requirement is derived from this broadly deontological conception of rationality.32 And third, internalist constraints on rationality are derived from the Reflective Access Requirement and used in explaining intuitive Bonjour (1985, p.8): “The idea…of being epistemically responsible in one’s believings, is the core of the notion of epistemic justification.” 32 Bonjour (1985, p.10): “If a given putative knower is himself to be epistemically responsible in accepting beliefs in virtue of their meeting the standards of a given epistemic account, then it seems to follow that an appropriate metajustification must, in principle at least, be available to him.” 31 22 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 judgements about cases.33 By contrast, I am proposing that we should proceed in the opposite direction of explanation. We begin with a characterization of the internalist constraints on rationality, which are motivated by reflection on intuitive judgements about cases. These internalist constraints contribute to an explanation of the truth of the Reflective Access Requirement. And the Reflective Access Requirement, in turn, contributes to explaining the nature of our conception of epistemic responsibility in reflective critical reasoning. Classical internalism is open to objections at every stage. First, rationality cannot be analyzed in such a way as to require epistemic responsibility. Epistemic responsibility is a distinctive kind of epistemic status that requires having an element of rational selfcontrol over one’s own habits of reasoning. It is a kind of epistemic status that is essential to our conception of ourselves as persons with a unified, self-conscious point of view on the world and so it is central to our interest in the concept of rationality. But it is not required for ground-level, unreflective rationality. Second, the Reflective Access Requirement cannot be derived from a more general deontological conception of responsibility uninformed by more basic internalist constraints on rationality. As we have seen, we need to appeal to these more basic internalist constraints in order to explain (i) the epistemic restriction to reflection alone in terms of which the requirement is formulated; (ii) the limits on the possibility of brute error; and (iii) the internalist constraints on the rationality of reflective access, which are illustrated by the case of the hyper-blindsighter. Moreover, our conception of the nature of epistemic responsibility in Bonjour (1985, p.42): “Norman’s acceptance of the belief…is epistemically irrational and irresponsible, and thereby unjustified, whether or not he believes himself to have clairvoyant power, so long as he has no justification for such a belief. Part of one’s epistemic duty is to reflect critically upon one’s beliefs, and such critical reflection precludes believing things to which one has, to one’s knowledge, no reliable means of epistemic access.” 33 23 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 reflective critical reasoning is informed by these more fundamental internalist constraints. Third, it is a mistake to suppose that the internalist constraints on rationality are derived from considerations about what is involved in higher-order reflective access. As I have construed them, the clairvoyance and brain-in-a-vat cases involve purely unreflective subjects. The internalist intuitions prompted by these cases are not intuitions about what is required for epistemic responsibility in reflective critical reasoning; rather, they are intuitions about what is required for ground-level, unreflective rationality. A common line of response to classical internalism involves endorsing a twolevel account of rationality, which combines a broadly externalist account of unreflective rationality with a more demanding account of reflective rationality that is designed to accommodate internalist intuitions.34 This kind of response is often motivated by appeal to a diagnosis of the internalist intuitions, according to which what they imply is not that rationality requires epistemic responsibility, but rather that rationality is incompatible with epistemic irresponsibility. The idea is to make room for the possibility that unreflective creatures may form rational beliefs in a way that is neither epistemically responsible nor irresponsible, since they lack the reflective capacities required for these kinds of epistemic evaluation to get a grip. However, a mere absence of epistemic irresponsibility is not sufficient for rationality, since a creature may be programmed by nature or nurture to employ irrational belief-forming methods, such as gambler’s fallacy, 34 Ernest Sosa (1991, 2003) proposes a distinction between apt belief, which is formed on the basis of exercising an intellectual virtue (roughly, a belief-forming disposition that is reliable in the circumstances) and justified belief, which is part of a coherent higher-order perspective on one’s beliefs as deriving from intellectual virtue. He also proposes a related distinction between animal knowledge, which is belief that is both apt and true, and reflective knowledge, which is belief that is not only apt and true, but also justified. See also Bach’s (1985) distinction between a person’s being justified in holding a belief and the belief itself being justified. 24 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 without being epistemically irresponsible in so doing.35 Therefore, if it is to succeed, the two-level account must be able to distinguish on the basis of purely externalist resources between the rational and the irrational belief-forming methods that can be employed unreflectively, in the absence of epistemic responsibility or irresponsibility. If my diagnosis of the internalist intuitions is correct, then this cannot be done. I have argued that there are distinctively internalist constraints on which belief-forming methods can be employed rationally, but unreflectively. Clairvoyance, for instance, is a belief-forming method that is irrational because it fails to satisfy these constraints. But the irrationality of clairvoyance cannot be explained in terms of epistemic irresponsibility because clairvoyance is a belief-forming method that can be employed unreflectively, by creatures that lack the reflective capacities required for this kind of epistemic evaluation to get a grip.36 In other words, the two-level account fails to capture the internalist constraints on unreflective rationality. A further consequence is that the two-level account is unable to appeal to a more fundamental internalist conception of rationality in explaining our conception of epistemic responsibility in reflective critical reasoning. The background assumption I am rejecting is put succinctly by Paul Boghossian, who says, “The core distinction between externalism and internalism in the theory of justification is properly characterized in terms of the notion of epistemic responsibility” (2001, p.41). In my view, the core distinction is more fundamental than that – it applies even at the unreflective level, whereas considerations of epistemic responsibility and irresponsibility only get a grip at the level of reflective critical reasoning. Moreover, our 35 See Pryor (2001), and references therein, for examples of this kind. Sosa’s view is that clairvoyant beliefs are apt, but not justified, while Bach’s view is that clairvoyant beliefs are justified, although clairvoyant subjects are not justified in holding those beliefs. Both views fail to capture the irrationality of employing clairvoyance unreflectively as a belief-forming method. 36 25 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 conception of epistemic responsibility and irresponsibility in reflective critical reasoning is informed by a more fundamental internalist conception of rationality which applies at the unreflective level. These points have been widely overlooked by many of the major players in the internalism/externalism debate.37 6. Conclusion The debate between internalists and externalists tends to oscillate between two extremes. On the one hand, internalist theories tend to impose implausibly demanding requirements on the reflective capacities of rational subjects, thereby ruling out the possibility of unreflective rationality. On the other hand, externalist theories tend to make room for the possibility of unreflective rationality only by obscuring the distinction between rationality and reliability. This dialectical situation is exacerbated by the fact that we lose sight of the significance of this distinction insofar as we restrict our focus to cases of unreflective rationality alone. The point and interest of the concept of rationality fully emerges only in the context of its role in a practice of reflective and epistemically responsible critical reasoning. However, it simply does not follow that the rationality of a belief is constituted in a way that makes essential reference to the subject’s reflective capacities. In order to reach a satisfactory resolution of the debate between internalism and externalism, we need a theory of rationality that can make sense of the possibility of unreflective rationality without losing the connection with the kinds of reflective critical In my view, these issues are bypassed altogether by versions of “mentalism without accessibilism”. According to such theories, what it is rational for the subject to believe supervenes on his factive or nonfactive mental states, but need not be accessible to the subject on the basis of reflection alone. For examples of non-factive mentalism, see Conee and Feldman (2001), Wedgwood (2001) and Pollock and Cruz (1999); for factive mentalism, see McDowell (1995) and Williamson (2000). 37 26 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 reasoning that provide the point of the concept of rationality. The theory I am proposing is intended to occupy this elusive middle ground.38 References Alston, William (1988b) “The Deontological Conception of Epistemic Justification,” Philosophical Perspectives 2: 257-99. Bach, Kent (1985) “A Rationale for Reliabilism,” The Monist 68: 246-63. Bermudez, Jose Luis (2003) Thinking Without Words. Oxford University Press. Boghossian, Paul (2001) “How Are Objective Epistemic Reasons Possible?” Philosophical Studies 106: 1-40. Bonjour, Laurence (1980) “Externalist Theories of Empirical Knowledge,” reprinted in (ed.) Kornblith, Epistemology: Internalism and Externalism, Blackwell, 2001. Bonjour, Laurence (1985) The Structure of Empirical Knowledge, Harvard University Press. Bonjour, Laurence and Sosa, Ernest (2003) Epistemic Justification, Blackwell. Brewer, Bill (1995) “Mental Causation: Compulsion by Reason,” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, Supplementary Volume, 69: 237-53. Brewer, Bill (1999) Perception and Reason, Oxford University Press. Burge, Tyler (1996) “Our Entitlement to Self-Knowledge,” reprinted in (eds.) Ludlow and Martin, Externalism and Self-Knowledge, CSLI, Stanford. Burge, Tyler (1998) “Reason and the First-Person,” in (eds.) McDonald, Smith and Wright, Knowing Our Own Minds, Oxford University Press. 38 My thanks to Paul Boghossian, Bill Brewer, Anna-Sara Malmgren, Christopher Peacocke, James Pryor, Karl Schafer and Crispin Wright. 27 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 Conee, Earl and Feldman, Richard (2001) “Internalism Defended,” in (ed.) Kornblith, Epistemology: Internalism and Externalism, Blackwell, 2001. Goldman, Alvin (1999) “Internalism Exposed,” reprinted in (ed.) Kornblith, Epistemology: Internalism and Externalism, Blackwell, 2001. Gopnik, Alison and Graf, Peter (1988) “Knowing How You Know: Children’s Understanding of the Sources of their Knowledge,” Child Development 59: 1366-1371. Martin, Michael (unpublished) “On Being Alienated”. McDowell, John (1994) Mind and World, Harvard University Press. McDowell, John (1995) “Knowledge and the External,” reprinted in his Meaning, Knowledge and Reality, Harvard University Press, 1998. Millar, Alan (2004) Understanding People: Normativity and Rationalizing Explanation, Oxford University Press. Peacocke, Christopher (1996) “Entitlement, Self-Knowledge and Conceptual Redeployment,” reprinted in (eds.) Ludlow and Martin, Externalism and Self-Knowledge, CSLI, Stanford. Pollock, John and Cruz, Joseph (1999) Contemporary Theories of Knowledge, Rowman and Littlefield. Pryor, James (2001) “Highlights of Recent Epistemology,” British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 52: 95-124. Sosa, Ernest (1991) Knowledge in Perspective, Cambridge University Press. Sosa, Ernest (2003) “Beyond Internal Foundations to External Virtues,” in Bonjour and Sosa (2003) Epistemic Justification, Blackwell. 28 Declan Smithies (NYU) February 16, 2016 Strawson, Peter (1962) “Freedom and Resentment,” Proceedings of the British Academy 48: 187-211. Wallace, Jay (1994) Responsibility and the Human Sentiments, MIT Press. Wedgwood, Ralph (2002) “Internalism Explained,” in Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 65: 349-369. Williamson, Timothy (2000) Knowledge and Its Limits, Oxford University Press. Williamson, Timothy (forthcoming) “On Being Justified in One’s Head”. Wolf, Susan (1990) Freedom Within Reason, Oxford University Press. Wright, Crispin (1989) “Wittgenstein’s Rule-Following Considerations and the Central Project of Theoretical Linguistics,” in (ed.) George, Reflections on Chomsky, Blackwell. 29