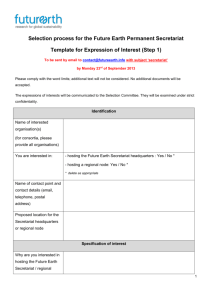

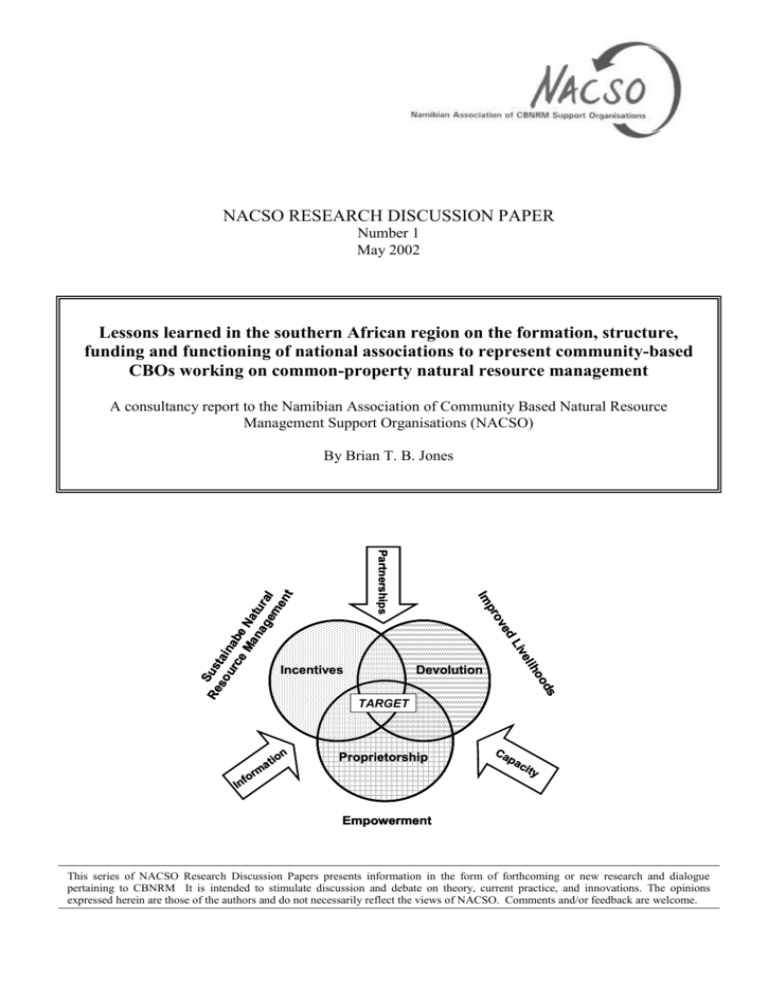

Lessons learned in the southern African region on the formation

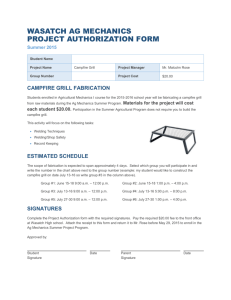

advertisement