International Trade Answer Key: Chapter 2-4 Economics

advertisement

ANSWERS

Chapter 2

True/False

1. False: consumers of the exported good lose as its price increases.

2. True.

3. False: producers of the domestic import-competing good see lower prices for their goods.

4. True.

5. True: but both are rare at times!

Multiple Choice

1. A

2. A

3. C

4. A

5. C

Problems

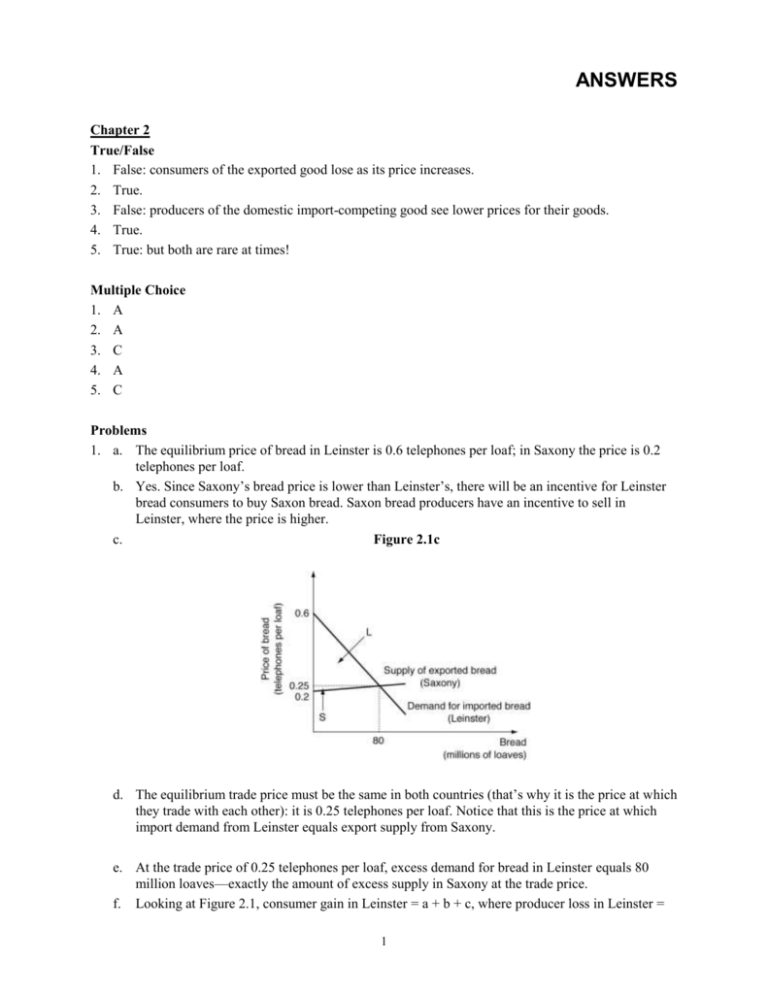

1. a. The equilibrium price of bread in Leinster is 0.6 telephones per loaf; in Saxony the price is 0.2

telephones per loaf.

b. Yes. Since Saxony’s bread price is lower than Leinster’s, there will be an incentive for Leinster

bread consumers to buy Saxon bread. Saxon bread producers have an incentive to sell in

Leinster, where the price is higher.

c.

Figure 2.1c

d. The equilibrium trade price must be the same in both countries (that’s why it is the price at which

they trade with each other): it is 0.25 telephones per loaf. Notice that this is the price at which

import demand from Leinster equals export supply from Saxony.

e. At the trade price of 0.25 telephones per loaf, excess demand for bread in Leinster equals 80

million loaves—exactly the amount of excess supply in Saxony at the trade price.

f. Looking at Figure 2.1, consumer gain in Leinster = a + b + c, where producer loss in Leinster =

1

a; consumer loss in Saxony = d; and producer gain in Saxony = d + e.

g. Bread consumers in Leinster and bread producers in Saxony will be happy about the opening of

free trade. However, Leinster bread producers will not be happy (they are undercut by cheaper

imported Saxon bread), nor will Saxon bread consumers, who used to pay a lower price before

the people in Leinster were able to buy the bread.

h. The net gain to Leinster is the area labeled “L”; this is equal in magnitude to the net gain b + c

from the domestic graph. The net gain to Saxony is the shaded area labeled “S”; this is equal in

magnitude to the net gain e from the domestic graph.

i. The country with the less elastic trade curve (usually the result of less elastic domestic supply

and demand curves) will gain the most from trade. In our case, this is Leinster. It was able to

“drive” the price it pays for bread far below its previous domestic bread price. As a percentage of

the free-trade price, Leinster’s price for bread changed 140 percent, whereas in Saxony the price

changed only 20 percent.

j . The losses from closing trade would just be the net gain the countries had obtained from free

trade: “L” in Leinster, “S” in Saxony.

2. With more elastic domestic supply and demand curves, Leinster’s import demand curve will also

become more elastic. Using Figure 2.1c as a guide, you can see that, as a consequence of an increase

in elasticity, the international price of bread will rise, and be closer to Leinster’s pre-trade price. The

quantity of bread traded will rise; Leinster’s net gains from trade will fall, but Saxony’s gains will

rise.

3. They would lose 5 percent per board-foot on the 48 billion board-feet they continue to sell at home,

plus sell four billion less board-feet in total, summing to a total loss of $2.5 billion.

Price of lumber

(per board-foot)

Figure 2.3

0.30

0.25

Supply (U.S.)

a

bc

d

Demand (U.S.)

40 48 52

Producer surplus loss

Lumber in billions of board-feet

= a + b + c : price decline on remaining sales

+d : reduction in total sales

= $2.4 billion

+0.1 billion

$2.5 billion

2

4. a. Bean consumers will lose and bean producers will gain as the relative price of beans rises; jeans

consumers will gain and jeans producers will lose as the relative price of jeans drops.

b. The net national gain from trade can be measured as the difference in the size of the consumer

and producer surpluses as a result of the opening of trade.

Chapter 3

True/False

1. True: that was David Ricardo’s point.

2. True: with constant costs, the opportunity cost of a good is the same, regardless of tastes.

3. True.

4. False: Arbitrage means everyone will pay the same price.

5. False: As long as a comparative advantage exists, trade will benefit even “unproductive” countries.

Multiple Choice

1. D

2. B

3. A

4. A

5. B

Problems

1. a. Leinster has an absolute advantage in both goods since it takes less labor to make bread and less

labor to make telephones than in Saxony.

b. Leinster has a comparative advantage in telephones; in Leinster, the price of one telephone is 5/3

of a bread loaf, while in Saxony the price of one telephone is 5 loaves of bread. At the same time

Saxony has a comparative advantage in bread: in Saxony, the price of one loaf is 1/5 telephone,

while in Leinster the price of one loaf of bread is 3/5 telephone.

2.

There is a basis for trade: Saxons can buy inexpensive telephones from Leinster and sell their

bread there for a higher price than at home. Leinsterian telephone manufacturers can sell in

Saxony for more than the pre-trade price; consumers in Leinster can buy bread more cheaply

from Saxony.

3

3. a.

Figure 3.3a

b. At a price of one telephone per four loaves of bread, Saxony will export bread to Leinster in

exchange for telephones.

c. With complete specialization, Leinster produces at point T, and Saxony produces at point B.

Each country can then trade their good for the other country’s good, at a price of one telephone

for four loaves of bread. The “consumption possibilities curve” is just the ray emanating from the

production point with slope 1/4. Notice that the consumption line lies outside each country's

production possibilities curve. That’s a good illustration of the benefits that come from trade.

Figure 3.3c

4

4. a.

Figure 3.4a

Cloth (yards)

The pre-trade price is calculated from the slopes of the PPCs, which are constant. In Chile, the

price of one yard of cloth is 1.5 bushels of wheat, and the price of one bushel of wheat is 2/3 yard

of cloth. In Brazil, the price of one yard of cloth is 2.5 bushels of wheat; the price of one bushel

of wheat is 2/5 yard of cloth.

b. Chile is the low-cost cloth producer; Brazil is the low-cost wheat producer. Thus, Chile will

export cloth; Brazil will export wheat. But the maximum that Brazil will pay for one yard of

cloth is 2.5 bushels of wheat (its own pre-trade price).

c.

Figure 3.4c

500

Brazil after productivity growth

Brazil

200

Chile

300 500

Wheat

(bushels)

With this change in the productivity of labor in cloth, Brazil’s PPC rotates upward, and the country’s

pre-trade price for a yard of cloth changes from 2.5 bushels of wheat to 1 bushel of wheat. Now,

Brazil is the low-cost cloth producer and Chile is the low-cost wheat producer. The trade patterns

will be reversed!

5. Suppose that you, as the older sibling, are absolutely better at washing dishes and taking out the

garbage. Your younger brother could do these chores too, but he is absolutely worse at them than

you. It is likely, however, that his comparative disadvantage lies in washing the dishes. Your parents

could have you do a less-than-complete job on both tasks by splitting your limited time between them

and let your brother go ride his skateboard. It would be more efficient (and more equitable) to have

you focus on washing the dishes well, and let your brother use his labor resources to take out the

garbage.

5

To be more precise: Let’s say it takes you 15 minutes to do the dishes and five minutes to take out

the trash. Your brother, on the other hand, would need 45 minutes to wash the dishes properly, and

ten minutes to take out the trash. Clearly you have an absolute advantage in “production” of these

services.

Labor to do

dishes (minutes)

Labor to take out

trash (minutes)

You

Your brother

15

45

5

10

Notice your brother has a comparative advantage in taking out the trash. While he would have to

“give up” 4 1/2 trash runs to do the dishes, you would only lose out on doing three runs.

Alternatively, you could say that the cost to you of taking out the trash is getting one-third of the

dishes done, whereas the cost to your brother is getting less than one quarter of them done. You are

the low-cost producer of clean dishes; your brother is the low-cost producer of trash disposal.

Chapter 4

True/False

1. False: it is the abundance of land relative to other factors that matters.

2. True: with increasing costs, there will come a point at which the opportunity cost of producing

another unit is far greater than anyone would be willing to pay for that extra unit.

3. True.

4. True.

5. True. In H-O, it is because factor intensities differ that differing relative endowments of those factors

across countries will lead one country to have a comparative advantage over another in the

production of the good that intensively uses its abundant factor.

Multiple Choice

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

A

A

B

D

A

Problems

1. a. The ratio of land to labor in Leinster is 8 million acres to 2 million laborers or 4:1. The ratio in

Saxony is 2 million acres to 400,000 laborers or 5:1. Therefore, although Saxony has absolutely

fewer acres of land than Leinster, Saxony is “land abundant.” Leinster is the “labor abundant”

country since it has one laborer for each four acres.

b. Telephones are labor-intensive goods; bread is land-intensive. According to H-O, then, Leinster

will export telephones and import bread; Saxony will export bread and import telephones.

6

2. In this case, we have to modify our measurement of “labor.” Now, although Leinster has more

workers, Saxony’s workers supply more days of labor per person per week.

So, if we were to measure factor abundance as the ratio of person-days to acres, we would get the

following:

For Leinster: Labor/Acres = (10 million person-days)/8 million acres = 1.25

For Saxony: Labor/Acres = (2.8 million person-days)/2 million acres = 1.40

So Saxony now looks like the relatively labor-abundant country!

3.

Figure 4.3

The PPCs of the two countries can be represented by the one drawn. The country with tastes skewed

toward pizza will have a higher pre-trade price for pizza in terms of beer than the country that has

tastes skewed toward beer. The two countries should trade: the pizza-loving country will produce

more beer and export it in exchange for pizza; the beer-loving country will make more pizza and

export it in exchange for beer, such as with points PL and BL. We get the interesting result that trade

causes each country to specialize less in production—at some middle point like P*—and trade for the

preferred good.

4. It doesn’t really matter what each country’s supply and demand curves (or production possibilities

and indifference curves) look like; what drives trade is what autarkic price results from those curves.

7

For example, the two countries illustrated below have very different demand and supply curves. And

yet, they do not have any obvious reason to trade with each other because those very different curves

yield exactly the same pre-trade price!

Figure 4.4

5. Heckscher and Ohlin don’t have much to say in this case. Factor endowments will still determine

relative factor prices (so that the labor-abundant country will tend to have lower wages than the

capital-abundant country), but we can’t predict what the pre-trade prices of the goods will be if labor

and capital are equally suited to producing both goods.

Chapter 5

True/False

1. True.

2. False: just the reverse is the case, with owners of scarce factors seeing their incomes fall.

3. True: that’s why Joan Robinson will never receive the prize for her work on imperfect competition–

proof that it is an imperfect world!

4. True.

5. True: unskilled labor is used relatively more in the import-competing industries in the United States.

Multiple Choice

1. C

2. A

3. B

4. A

5. D

8

Problems

1. When trade opens up, the price of bread falls in Leinster and rises in Saxony. At the same time, the

price of telephones rises in Leinster and falls in Saxony.

a. In the short run, Leinster’s bread workers see their wages fall, while telephone workers see their

wages rise. In the long run, all workers see their wages rise as labor moves out of the declining

bread industry and into the labor-intensive telephone industry.

b. In the short run, Saxony’s bread workers see their wages rise, while telephone workers see their

wages fall. In the long run, all workers see their wages fall as labor is released from the

labor-intensive telephone industry but is not needed in the same amounts in the land-intensive

bread industry.

c. If the factor price equalization theorem holds, the wages of the abundant workers in Leinster

should rise to meet the falling wages of the scarce workers in Saxony. Similarly, the scarce land

in Leinster will earn less than before, abundant land in Saxony will earn more than before, and

they should equal each other if FPE holds.

2. Some possible explanatory factors include: trade barriers that prevent commodity price equalization;

differences in labor productivity or skill levels between the countries; and immobility of labor

between sectors in each country.

3. a. If a factor is immobile between sectors, its income is a function of whether it is employed in the

price-rising industry or in the price-falling industry. So capital owners, landowners, and laborers

in the computer sector would gain; capital owners, landowners, and laborers in the wheat sector

would lose.

b. If a factor is mobile between sectors, its income is a function of whether it is the country’s

relatively scarce factor or relatively abundant factor. So capital owners would gain and

landowners would lose. Labor would migrate from the losing sector to the gaining sector.

4. a. Bread is more labor-intensive than wine: 4/9 of the cost of making bread is labor cost, whereas

only 1/3 of the cost of making wine is labor cost. Conversely, wine is capital-intensive.

b. If inputs cannot move between sectors, everyone in the wine sector will likely gain and everyone

in the bread sector will likely lose.

c. Since bread prices are pushed down, bread consumers will celebrate open trade. But since wine

prices rose, wine consumers will commiserate with the bread makers.

5. This is a case of reversing the Stolper-Samuelson effects of free trade. Now, bread will be the pricerising industry and telephones will be the price-falling industry.

a. Because labor is intensively used in the price-falling industry, real wages will fall by more than

14% (due to the magnification effect).

b. Conversely, real land rents in Leinster will rise by more than 14%.

9

Chapter 6

True/False

1. True. For example, if the United States exports $1 billion worth of Coors beer and imports $1billion

worth of Heineken beer, net trade in beer is zero, but intra-industry trade in beer is $2 billion.

2. False: IIT is more prevalent in imperfectly competitive industries.

3. False: economies of scale reduce average costs.

4. True: Consumers of the export good may benefit both from product differentiation and from cost

reductions that result from scale economics in production.

5. False: In intra-industry trade, factor incomes are relatively unaffected because, as imports of one

variety of product increase, exports of another variety expand as well. So we would expect exports of

fine riding boots from England to rise as well-made Swiss hiking boot imports to England also rise.

So employment and incomes of workers in the British footwear industry are relatively unchanged.

But the increased variety of footwear available raises the well-being of those workers in their role as

buyers of shoes. This might be an example of product differentiation being founded on peculiarities

of each country: the passion for horse racing in England and for mountain climbing in Switzerland.

Multiple Choice

1. B

2 B

3. B

4. B

5. B

Problems

1. a. Recall from Figure 2.1 that Leinster imports 80 million loaves of bread from Saxony; in return it

exports 20 million telephones because the “price” of the imported bread is 0.25 telephones per

loaf. So, for Leinster:

IIT Share = 1 –

=1–

=1–

=1–

sum of X M

sum of (X M )

{ X telephones M telephones X bread M bread }

{( X t M t ) (X b M b )}

{ 20 0 0 80 }

{( 20 0) (0 80)}

100

100

=0

In other words, there is no intra-industry trade between the two countries: there is only a straight

barter of Leinster’s telephones for Saxon bread. This is entirely consistent with Heckscher-Ohlin;

in their model, all trade is based on swapping different goods that are manufactured using

different relative factor endowments.

b. Recall the notion of product differentiation and the increased importance of luxuries as incomes

rise. It is possible that the Leinster bakers who are still in business (recall that we do not have

complete specialization in our hypothetical world) might switch from baking the universal,

generic white bread to baking specialty breads and pastries. In that case “bread” (as broadly

defined) will be exported from Leinster to Saxony.

10

2. Under a situation of identical tastes and production possibilities, we could not turn to standard theory

for why countries would trade (i.e., differences in pre-trade price ratios arising from different tastes).

Instead, countries could gain by trading with each other if the goods they produce and buy are subject

to economies of scale. For example, suppose both the U.S. and Germany can produce ships or

airplanes under the same conditions of increasing returns to scale in both products. Suppose they

both had the same tastes, causing each country to “consume” ships and airplanes. The countries

could gain from trade only if one country specialized in ships and the other specialized in airplanes.

With all conditions identical, they could even flip a coin to see who specializes in what.

Figure 6.2

Ships

(In thousands)

100 B

D

60

I1

30

A

I0

40

C

60

Airplanes

(In thousands)

In Figure 6.2, both countries could gain as they move from the common production point A to point

B for the ship specialist and point C for the airplane specialist. The two countries could then

consume at point D.

3. We are likely to see the rise of intra-industry trade in liquor between the U.S. and France. Consumers

in each country will benefit from a greater variety of alcoholic beverages (both domestic and

imported) at lower prices. Think of it: cheaper Jack Daniels! Cheaper Remy Martin!

4. IIT share = 1 – [sum of absolute value of (X – M)]/(sum of X + M)

a. With Japan: IIT = 1–{(75 – 60 + 70 – 150)/ (145 + 120)}

IIT = 0.817

With Sudan: IIT = 1–{(50 – 55 + 70 – 0)/ (115 + 55)}

IIT = 0.559

b. IIT with Japan is higher than IIT with Sudan. This is also likely true in the real world because IIT

is largely based on a rising demand for knowledge-intensive luxuries. The higher the level of

consumer income, the greater the proliferation of near-substitute varieties of goods and services.

Higher incomes make it possible to value variety for its own sake. Thus, since the United States

and Japan have higher income levels, they are buying each others’ version of similar products

(e.g., cars, entertainment equipment, etc.).

5. The standard H-O model suggests that the opening of trade in computers would reduce the well-being

of domestic buyers of computers by raising the price they must pay. But we might also consider the

possibility that economies of scale exist: when domestic computer manufacturers face additional

demand from Eastern Europe, production will increase. With scale economies, costs will fall as

production expands. As a result, domestic computer buyers may actually end up better off due to

lower computer prices.

11

Chapter 7

True/False

1. True.

2. True.

3. True! Ask the people who raised you.

4. False: export-based growth tends to raise trade volumes.

5. True insofar as isolation cuts the country off from new technologies that could raise productivity in

the country.

Multiple Choice

1. C

2. C

3. A

4. D

5. B

Problems

Figure 7.1

a. Saxony is experiencing export-biased growth. We would expect the volume of trade between

Saxony and Leinster to increase—the Saxon telephone industry will decline (Rybczynski), and

Saxony will import more telephones from Leinster instead.

b. Since Saxony is a small country, we would not expect bread’s trade price to change.

Consequently, Saxony can reach a higher level of utility as the new indifference curve suggests.

c. Leinster is experiencing “export-biased decline.” We would expect that the volume of trade

between Leinster and Saxony would fall. In a reverse of immiserizing growth, the level of

economic welfare in “large country” Leinster might actually rise: the terms of trade will move in

its favor as the supply of telephones (and likely the demand for bread) fall. Whether or not

welfare does rise will depend on the degree to which prices change and on the shape of

Leinster’s indifference curves.

This is a good example of how economic analysis can miss the broader picture: although the

terms of trade move in favor of Leinster, it is the result of a human catastrophe.

12

2. a. This export-biased growth may result in a reduction in Canadian well-being (a case of

immiserizing growth) if the price of wheat falls far enough and if Canada is highly dependent on

international trade in wheat and cloth.

b. The rest of the world will gain as a result of the decrease in the price of wheat.

c. The Rybczynski theorem tells us that the cloth sector will contract as the wheat sector expands.

Because the wheat sector absorbs fewer unskilled laborers than the cloth sector releases unskilled

wages will fall.

d. Canada should benefit from an increase in the world’s supply of labor. This will tend to reduce

the price Canada pays for cloth and increase the price (and quantity) of Canada’s wheat exports.

3. Not only can growth affect trade, but openness to trade can affect growth. Because Leinster has a

large telephone industry, it is likely that R&D there is significant. Productivity in Saxony may

increase as more technologically sophisticated imported telephones reduce the costs of doing

business in that country. At the same time, telephone producers in Saxony will have to innovate and

improve their products to compete with the imported units; some of the Leinsterian technology may

even be diffused into Saxony. Clearly, this can be good for Saxony.

4. a. According to H-O, Kazakhstan will export land-intensive and unskilled-labor-intensive goods. It

will import capital-intensive and skilled-labor-intensive goods.

b. To achieve import-biased growth to replace imports with a domestically-produced substitute,

Kazakhstan would need to increase its endowments of capital and skilled labor. If Kazakhstan

were a large country, this would turn the terms of trade in its favor: the price of imports in

particular would fall as the demand for them from Kazakhstan declines. As you might have

guessed, however, there are few (if any) goods for which Kazakhstan could have an impact on

the price.

5. a. This would be a case of import-biased growth: oil imports should fall.

b. In a strict one-dollar one-vote metric, well-being will rise as the terms of trade move in favor of

the U.S.

c. If the expansion of the oil sector is large enough, the Dutch disease could very well plague the

U.S.

d. Here, you should think about externalities—both positive and negative—to increased production

of oil and decreased production of other goods.

6. Assuming the increased savings on the part of American consumers will be transferred to investors

and not just hoarded under our collective national mattress, the rate of capital formation in the

economy should increase. This would amount to export-biased growth of a large country. In theory,

this would raise trade volumes with the rest of the world, while reducing the price of American

exports and increasing the price of imported goods. At an (unlikely) extreme, this could result in

immiserizing growth if the adverse terms-of-trade movement offsets any gains in our ability to

produce capital-intensive goods.

Chapter 8

True/False

1. False: a tariff may be welfare-increasing for a large country, but such a tariff always reduces world

welfare.

2. False: that is characteristic of an ad valorem tariff.

3. True, at least until Chapters 10 and 11 explore some counter-examples.

4. False: but you may think so at the end of the sections on tariffs.

5. True.

13

Multiple Choice

1. A

2. D

3. C

4. D

5. D

Problems

1. In Figure 8.1, the tariff that reduces imports from 80 million loaves to 40 million loaves raises the

price in Leinster to 0.44 telephones per loaf and reduces the price in Saxony (the “world price”) to

0.23 telephones per loaf.

a. Consumer surplus in Leinster falls by a + b + c + d; in Figure 8.1: consumer surplus in Saxony

rises by e + f.

b. Producer surplus in Leinster rises by a; in Figure 8.1: producer surplus in Saxony falls by e + f +

g + h + i.

c. To get the net change in welfare in Leinster, you must take into account that government tariff

revenues equal c + h. Therefore, the net change in welfare is (producer gain + government

revenue) – (consumer loss) = h – (b + d). Notice that, since the portion of the government

revenues coming from abroad (h) does not exceed the deadweight losses (b + d), this tariff is not

optimal for Leinster. And in Saxony, the tariff is a clear loss. The loss of producer surplus e + f +

g + h + i outweighs the gain in consumer surplus e + f.

d. The “world” welfare is reduced by the sum of the deadweights. On Figure 8.1 below, this shows

up as the triangles, b + d, and g + i.

Figure 8.1

2. a. The net U.S. national gain = the rectangle of foreign-price markdown [(3.00 – 2.50) x 300

million] – the triangle of deadweight loss [1/2 x (4.00 – 3.00) x (1200m – 300m)], for a total net

loss of $300 million in this case.

b. Unit value added with the tariff = $4.00 – $2.00 = $2.00. Unit value added without the tariff =

$3.00 – $2.00 = $ 1.00. The effective rate of protection for the beer industry, then, is (2.00 –

1.00) / 1.00 = 100 percent.

14

3.

Figure 8.3

Pbats

SUS

$100

$80

$65

a

b

c

e

d

P’world + tariff

Pworld

P’world

DUS

160 220 320 360

Qbats (000)

United States

Note that the U.S. is a “large country” when it comes to purchases of baseball bats: a $35 tariff

reduces the world price of bats from $80 to $65.

a. Bat consumers lose a total of $6.8 million, represented by area a + b + c + d.

b. Bat producers gain $3.8 million, represented by area a.

c. The government earns a tariff of $35 on each bat imported, for a total of $3.5 million, shown as

area c + e.

d. The net effect on well-being in the U.S. consists of government and producer gains totaling $7.3

million, minus consumer loss of $6.8 million. So, the net effect of the baseball bat tariff on the

U.S. is a gain of $500,000.

e. We don’t have numbers for all other countries in the world, but we do know that the bat buyers’

gain from the decrease in price will be less than bat producers’ losses, so there will be a net loss

for the rest of the world.

f. The net loss for the rest of the world will exceed the net gain to the U.S. because we know that in

each country the tariff causes deadweight losses.

4. If the effective rate of protection on clothing is less than zero, it indicates that trade policies of

Pakistan reduce the value added per unit of clothing. This can occur if tariffs on the inputs to clothing

(i.e., textiles) are higher than tariffs on imports of clothing. To provide the clothing industry more

protection, tariffs on imported textiles can be reduced, or tariffs on imported clothing can be raised.

5. Another way of measuring the effective rate of protection is

[toutput] – [share][tinput]

1 – share

where toutput is the tariff rate on the final good

tinput is the tariff rate on the imported input

and

share is the share of the imported input in the final good’s value under free trade

In this problem, the e.r.p. equals

[0.12] – [0.10][0.10]

= 0.122, or 12.2% .

1– [0.10]

In general, when the tariff on the final good exceeds the tariff on the imported inputs, the e.r.p. will

exceed the tariff on the final good.

6. Leinster’s import demand is much less elastic than Saxony’s export supply. (This should not be

surprising, since bread is a staple/necessity.) So if Leinster places a tariff on Saxon bread it is almost

certain that welfare in Leinster will decrease. (We can say with certainty that welfare will decrease

only if the supply of exported bread is infinitely elastic, and that is not the case here.)

15

Chapter 9

True/False

1. True.

2. False: insofar as a quota allows a domestic producer to act as a monopolist, the quota will reduce

welfare for the country that imposes it.

3. True: the U.S. government collected much of its revenues from tariffs for the first 50 to 100 years of

its existence.

4. True, if they had been auctioning the quota licenses.

5. True!

Multiple Choice

1. C

2. B

3. C

4. B

5. A

Problems

1. You should refer back to Figure 8.1. The illustration of a tariff that reduces imports to 40 million

loaves is the same as a quota or VER that reduces imports to 40 million loaves.

a. A quota can be a very effective way of reducing imports; it strictly limits quantities, whereas

tariffs do not. The quota licenses can be auctioned to the highest bidders (thus gaining revenues c

+ h) or can be passed out as political favors—buying votes or “good behavior.” The Leinster

government should be aware that a domestic bread monopolist may arise under the protection of

the quota, and this would be a welfare-reducing event.

b. Leinster could try to force a VER of 40 million loaves on Saxony. Then either the

first-at-the-dock Saxon exporters get a windfall from the higher price paid for their bread in

Leinster, or the Saxon government could auction export licenses and capture the revenues

(c + h) for itself. Either way the Leinster government doesn’t get any revenues when it

implements a VER, but it gets to appear as if it still promotes free trade.

Figure 9.2

Telephones

(loaves/phone)

2. a.

5

4.25

4

SS

R

DS

M2

M1

Saxony

16

Telephones

Suppose Saxony places a tariff of 0.25 loaves of bread per telephone on imports. As a small

country, this merely raises the Saxon price of telephones to 4.25 loaves of bread per telephone,

reducing imports from the free trade level of M1 to a level of M2. Suppose, instead, the Saxon

Minister of Trade had decreed an import quota of M2. This would exactly push up the price of

telephones in Saxony from the free trade level of 4 loaves/telephone to the quota-barriered price

of 4.25 loaves/telephone.

b. The Saxon Ministry of Trade could allocate quota licenses by:

i. auctioning them to the highest bidder, who would pay, at most, the difference between what

she pays in Leinster for telephones (4 loaves of bread) and what she can sell the telephones

for in Saxony (4.25 loaves of bread).

ii. The Minister of Trade can give the import rights to his brother-in-law Dave (an example of

fixed favoritism or nepotism), in which case Dave has a windfall of R and should be very

nice to the Minister at all future family reunions.

3. In Johnson’s technique, we express the deadweight losses from trade restriction as a percentage of

GDP. Referring to Figure 8.1, you can see that the area of the deadweights b + d is

(1/2)(base)(height):

= (1/2)(80m loaves – 40m loaves) (0.44 telephones/loaf – 0.25 telephones/loaf)

= 3.8 million telephones

So the cost to Leinster of protecting its bread market is 1.9 percent of its GDP each year. This is not a

small number in itself, but it doesn’t even attempt to measure other costs such as enforcement (a

coast guard to keep bread smugglers under control) or possible retaliation by Saxony against

Leinster’s telephone exports. We might say this is offset somewhat by the government revenue

collected from Saxony’s bread exporters, but in this case the amount is trivial: on each of the 40

million loaves of bread imported, Leinster collects 0.02 telephones per loaf, for a total of 800,000

telephones, or 0.4 percent of GDP.

4. a. Government revenue = (license fee)(# imports allowed)

= ($50)(100,000)

= $5 million.

b. Producer surplus rises by the higher price received on all cameras sold by domestic suppliers

before the quota (= $7.5 million) plus the value of extra sales of domestic cameras generated by

the limit on imports (= $1.25 million). So producer surplus rises by a total of $8.75 million.

c. Consumer surplus falls by the higher price paid on the cameras consumers still buy (= $15

million) plus the value of consumer surplus lost by those buyers who drop out of the market due

to higher prices on cameras (= $1.25 million). So consumer surplus falls by a total of $16.25

million.

d. The net effect, subtracting consumer loss from the government’s and producers’ gains, is a loss

of $2.5 million. (Notice that this is exactly the value of the consumption and production

deadweights.)

17

5.

Figure 9.3

Price

(dollars per CD)

Supply of exports

$15

$12

$10

b+d

c

e

a

Demand for imports (U.S.)

8 10

CDs (millions)

a. The U.S. gains (e – b – d) = 13 with the import quota, assuming quota rents are kept in the

United States. With the VER, the United States “gains” (– c – b – d) = –27. From a “one-dollar,

one-vote” point of view, the import quota is far better for the United States.

b. With the import quota, exporting firms/countries “gain” (–e – a) = –18. With the VER, the

exporting firms/countries gain (c – a) = 22. So exporters would prefer a VER to an import quota.

Chapter 10

True/False

1. True.

2. True, though they are “first” in the hearts of die-hard patriots.

3. False.

4. True!

5. True.

Multiple Choice

1. D

2. C

3. D

4. A

5. B

Problems

1. There would definitely be a national welfare loss for Saxony from a telephone tariff. There would be

both a production effect and a consumption effect, which would not be offset by any terms-of-trade

effect.

To justify incurring that welfare loss, the Saxon government could make an infant industry argument.

Or it could present the telephone industry as somehow strategic in national defense (the ability to

communicate is crucial to a country). There are also important spillover benefits from light industry

that would not result from agricultural processing, such as electronic innovation. Of course, the

national pride issue might come up (as it has in the electronics sector in the U.S.).

If Saxony did not want to place a tariff on imported telephones (perhaps because it feared retaliation

18

2.

3.

4.

5.

from Leinster), it could subsidize the domestic telephone industry or provide funds for

telecommunications R&D. This, of course, will mean that the Saxon government will have to come

up with funds rather than collecting revenues as in a tariff.

What a one-dollar one-vote econometrician would want to know is whether the present value of all

the irretrievable deadweight losses associated with the tariff is larger or smaller than the value of the

increased producer surplus that might be obtained once the “infant” grows up to be a more efficient,

low-cost producer. Not only are the magnitudes of these losses and gains important, but an economist

would also want to take into account the “discounted present value” notion, which argues that the

benefit of a dollar received in twenty or thirty years has less absolute value than a dollar’s cost

experienced today.

Although Saxony is a small country and so cannot hope to levy a nationally optimal tariff on

Leinster’s telephones, there may still be an argument for the tariff. As long as the tariff is not

prohibitive, it will generate revenues to replenish the government’s resources to fight the disease. But

more importantly, this tariff fits the specificity rule. Use of telephones is creating a negative

externality in Saxony, raising the social cost of telephones above the private cost. Levying a tariff

raises the price of imported and domestically produced telephones, so consumption will likely fall, as

will the number of citizens developing brain tumors.

Tariffs are second-best methods for income redistribution: they have associated deadweight costs. On

the other hand, import protection might be a better solution than doing nothing at all, particularly if

those scarce factors of production are difficult to mobilize into new sectors after trade opens. A more

“efficient” means of addressing the problem is retraining those factors of production to work in

expanding (perhaps export) sectors. As we have seen in many industrialized countries, however, this

is easier said than done. In that case, a government subsidy to maintain the factor’s employment is a

less costly approach than an import tariff or quota.

The import tariff might be better than doing nothing—it depends on how high the tariff barrier is,

among other things. But the specificity rule warns that something else is probably better. Since the

problem is that firms lack the capital to see themselves through until the later increases in efficiency,

the government should lend funds to them. Alternatively, a temporary production subsidy is virtually

as good as a loan, although raising the tax rates to get revenue for the subsidy might have negative

incentives elsewhere in the economy.

Chapter 11

True/False

1. True.

2. True.

3. False, except insofar as countries go to war over trade!

4. True, but depending on the year, Japan rivals China as a steel exporter.

5. True.

Multiple Choice

1. C

2. B

3. A

4. D

5. D

19

Problems

1.

Price of telephones

(loaves per telephones)

Figure 11.1

Demand for imports

(Saxony)

4

a

b

3

c

World price

Price after

Export subsidy

700 800

Telephones (thousands)

If the Leinsterian government subsidizes the export of telephones to Saxony, it will reduce the price

Saxons have to pay. As Figure 11.1 shows, a subsidy could reduce the price from four loaves of

bread per telephone to three loaves of bread per telephone. This cost to Leinster will be the amount

of the subsidy times the number of exported units, or area a + b + c. Saxony, on the other hand, will

gain consumer surplus of a + b, as more units are imported at a lower price. As a result, the world as

a whole will lose area c. This represents wasted resources as Saxony buys “too many” telephones at a

price less than the cost of production (as embodied in Leinster’s original export supply curve).

2. a. Although cheap telephones are a boon for Saxon consumers, they represent a threat to Saxon

telephone manufacturers who must compete with the lower-priced (and probably below-cost)

imports. Some portion of the domestic industry is likely to go out of business. If telephones could

be considered a strategic good, or a product with beneficial spillover effects for the rest of the

economy, the Saxon government might want to counteract the subsidy. Plus, if Leinster is trying

to drive out Saxon import-competing producers to create an international monopoly (and later

raise prices above the competitive level), Saxony would want to nip this subsidy in its bud.

b. One reason Leinster’s government might subsidize telephone exports (although they are unlikely

to admit it) is to undercut the Saxon telephone industry and create a monopoly for the Leinster

industry. In this situation an export subsidy would act to finance predatory dumping. (This would

be more likely if some political patronage is involved, e.g., if government officials in Leinster

have a financial stake in telephone exports!)

But keep in mind that Leinster’s own telephone buyers are not going to be pleased about the

whole scheme. Not only are they taxpayers who have to fund the subsidies, but they will also end

up paying a higher domestic price for their telephones, since no Leinsterian producer will sell

them telephones at anything less than the subsidized price he receives for exported telephones.

c. If the Saxon government levies a countervailing duty of one loaf of bread per telephone, the price

of telephones in Saxony will return to four loaves per telephone, and exports will be reduced. In

Figure 11.1 this would be illustrated by an upward shift of the world price line back to its

original level.

Although Saxon telephone consumers won’t be happy, Saxon producers will no longer be

undercut by imports. In addition, the Saxon government now collects area a in duties on the

remaining 700,000 imported telephones. On the other hand, Leinster not only shells out area a in

subsidies on the remaining exports, but it has not ended up with any net increase in the quantity

of exports.

On net, this “strike-counterstrike” policy only results in Leinster’s subsidies being transferred

into the Saxony government coffers.

20

3. Assuming the domestic price in the exporting country is the price at which TVs left the factory

destined for domestic distribution, then both Philips and Sharp are guilty of dumping: 250 > 200 for

Philips; 325 > 310 for Sharp. RCA is not guilty of dumping because 300 = 300.

Alternatively, if you interpret “average unit cost” as the price at which TVs leave the factory for

domestic distribution, then only Philips is guilty (250 > 200), while Sharp is not (300 < 310), and

RCA is not (295 < 300).

4. In general, a firm has an incentive to dump if the good has a lower elasticity of demand at home than

abroad.

Consider Figure 11.4, in which Hibernian demand is inelastic and demand in the rest of the world

(ROW) is infinitely elastic.

Figure 11.4

PSteel

PH

MCRigid Inc.

PRow

MRRow = DRow

DH

MRH

QH

QTotal

QSteel

As a profit-maximizing company, Rigid Inc. will produce where MR = MC, at a level of Qtotal.

Because re-export of steel is costly, Rigid Inc. can price discriminate, charging PH for sales of QH in

Hibernia and PROW for exports of Qtotal – QH to the rest of the world.

5. You can see from Figure 11.5a given in the guide that Venezuela is a large country when it comes to

coffee. With the export subsidy, Venezuelan growers will export 1 million pounds of coffee to the

rest of the world at a price of $9 per pound; on top of this they will receive a $2 per pound subsidy

for a net price of $11 per pound. (And this is what they will charge Venezuelan consumers for a

pound of coffee.) When the export subsidy is removed, the world price rises to $10 per pound and

exports drop to 600,000 pounds.

After the subsidy, production and exports of coffee both decline, as does the price that Venezuelan

growers receive. In Figure 11.5b, you can see that they lose area a + b + c, which totals $2.9 million.

On the other hand, Venezuelan coffee drinkers win: now they pay the world price of $10 per pound.

They gain area a + b, which totals $2.1 million. And the Trade Minister is especially pleased to hear

that the government no longer has to cough up export subsidies that had totaled $2 million. In fact,

you assure him that the country as a whole gains, on net, $1.2 million (the difference between the

government’s and the consumers’ gains and the producers’ losses).

To really strut your stuff, you tell the Minister that you’ll throw in an analysis of what happens in the

rest of the world, too. While the news is a bit grim for ROW coffee drinkers (they pay more and

import less, areas e + f + g, for a loss of $21.9 million), ROW coffee growers cheer, since they now

don’t have to try to compete with artificially cheap Venezuelan coffee. ROW producers gain area d,

which equals $21.1 million. So, unfortunately, the rest of the world loses $800,000 when the coffee

export subsidy ends.

21

But, you reassure the Trade Minister (who is now feeling guilty about all those unhappy coffee

drinkers in the rest of the world) that the world as a whole gains $400,000 by stopping the subsidy;

this is shown as the triangle bounded by the 3 dots on Figure 11.5a. You smile and inform him that

this is exactly the sum of the deadweight losses no longer incurred.

[P.S. Next time, find a more secluded beach to hang out on!]

6.

Figure 11.6

a. With this support price for bread, Leinsterian bakers now crank up their production while the

domestic consumers cut back on purchases. This creates a surplus of bread (AB) in Leinster.

Clearly, Leinster no longer will import bread. In fact, it is likely that this bread surplus—which

the government must buy up in order to maintain the support price—will become an exportable

commodity.

To recoup some of the cost of the support, the government can sell the bread on the world market

for whatever it will bear. This will be no more than the original free-trade price of 0.25

telephones/loaf; if Leinster can be considered a “large country,” the release of this excess bread

onto the world market could force the world price down.

Bread has become a switch-over good in Leinster, just as butter did under the real-world price

supports of the European Union.

b. Leinster’s bakers will have an enormous increase in their welfare: not only are they selling more,

but they are doing so at a higher price. The increase in producer surplus equals area a + f + g + h.

But consumer surplus loss equals a + b + c + f + g, which exceeds the producer gain, so the

residents of Leinster lose in the first instance.

At the same time, the Leinsterian government must buy up the excess bread on the market (AB)

at a price of 0.75 telephones/loaf. At best, this surplus can be resold on the world market for the

going price of 0.25 telephones/loaf, yielding an additional loss to the government (and so the

citizens) of (AB loaves) x (0.50 telephones/loaf). But as a large country, it is likely that this

exported Leinsterian surplus will bring in something less than the original world price, draining

the treasury even more.

This should, of course, make you wonder about the wisdom of price-support schemes. It seems

clear that they cannot be justified by the one-dollar, one-vote metric.

22

Chapter 12

True/False

1. True.

2. False: there may be welfare-decreasing trade diversion.

3. False: gains would be smaller.

4. True.

5. True.

Multiple Choice

1. C

2. B

3. C

4. B

5. B

Problems

1. With no tariffs between them, Leinster and Saxony could be considered a free trade area. To be a

customs union, however, they would have to have a common tariff against other countries of the

world, and remember—you have not been told that any countries exist in the “world” discussed here

except Leinster and Saxony!

Leaving aside the issue of the external tariff, Leinster and Saxony could be a common market if they

allowed the factors of production to move freely between the countries. For the two countries to

comprise an economic union, however, the governments in Leinster and Saxony would have to

develop joint fiscal and monetary policies.

You might want to speculate on the possibility of an agricultural nation joining together with an

industrial nation. That is to say, are there factors other than economic ones that could make this

problematic or beneficial?

2. Assume that the elasticity of demand and supply are the same.

Figure 12.2

23

If the U.S. joins a free trade area with Mexico (a higher-cost producer than South Korea), American

shoe consumers will gain area a + b + c + d (= $9,750), American shoe producers will lose area a

(= $4,250), and the U.S. government will lose tariff revenues c + e (= $10,000).

On net, the U.S. loses $4,500 from joining the free trade area with Mexico. The loss of tariff revenue

e is larger than the gain of deadweight losses b + d.

3.

Figure 12.3a

Price of telephones

(loaves per telephones)

Supply in Saxony

6

5 1/3

5

a

b

c

1 2/3

Demand in Saxony

Telephones

a. With an initial nondiscriminatory tariff of 4 1/3 loaves of bread, the price in Saxony of Leinster’s

telephones would be six loaves; the price of Avalon’s telephones would be 5 1/3 loaves. Under

this tariff, Saxony would initially produce its own telephones and import none, because domestic

telephones are less expensive than telephones imported from either Leinster or Avalon. However,

if the tariff were selectively removed on Leinsterian telephones, Saxon consumers would switch

to telephones imported from that country (at an untaxed price of 1 2/3 loaves per telephone). The

result is trade creation. As illustrated in Figure 12.3a, while Saxon telephone producers lose area

a, Saxon consumers gain areas a + b + c, for a net national gain of b + c.

Figure 12.3b

Price of telephones

(loaves per telephone)

Supply in Saxony

5

2 2/3

2

1/23

1

b

e

a

c

f

d

g

Demand in Saxony

Telephones

24

b. On the other hand, if the initial nondiscriminatory tariff had been 1 loaf of bread, the price of

Leinster’s telephones would be 2 2/3 loaves; the price of Avalon’s telephones would be 2 loaves.

Under this tariff, Saxony would import telephones from Avalon. However, if the tariff were

selectively removed on Leinster, Avalonian telephones would remain at the tariffed price of 2

loaves while Leinster telephones would enter without tariff at a price of 1 2/3 loaves. This

customs union would divert trade away from Avalon and towards Leinster. As illustrated in

Figure 12.3b, Saxon producers would lose area a, while Saxon consumers would gain area a + b

+ c + d + e. The Saxon government, however, loses all the tariff revenues it used to collect on

Avalonian imports, area c + d + f + g. As a result, Saxony incurs a net loss from this customs

union with Leinster. (Notice, however, that depending on the size of the revenue losses versus

the recovery of previous deadweights, Saxony might have an increase in its welfare from the

customs union with Leinster—just not as large a welfare gain as it would have if the customs

union had been with Avalon.)

4. a. For an embargo to be effective (in economic terms), the trade ban should reduce welfare in the

target country without causing much welfare loss to the people of the embargoing country. This

will be the case if import demand in the target country is low (inelastic) and export supply from

the embargoing country is high (elastic). Looking back at Figure 2.1c, you should see that

Saxony’s bread export curve is much more elastic than Leinster’s demand for imported bread.

(This is probably because bread is a staple food in Leinster.) So in economic terms, we would

expect the Saxon bread embargo to be economically effective.

b. Whether or not the Saxon embargo is politically effective will depend upon a number of things.

First, insofar as Saxony is a small country, the attempt to punish a larger country might bring

down upon Saxony unimaginable kinds of retaliation. In a broader sense, denying the export of a

necessary foodstuff could backfire politically and socially. (Recall some of the reactions to the

American embargo on wheat exports to the Soviet Union in the late 1970s.)

Chapter 13

True/False

1. True.

2. True: when the tax imposed on domestic producers reflects the social costs of the damage the

factories cause, it will raise the cost of production and so the autarky price of the good. If that

autarky price rises enough (i.e., above the world price), the country could turn into a net importer of

the good.

3. False: much of the conflict is between the “green” developed countries and the developing countries.

4. False: it doesn’t matter to whom the property rights are assigned, as long as they are assigned to one

of the parties.

5. True: as long as that world government assigns property rights.

Multiple Choice

1. E

2. C

3. A

4. D

5. C

25

Problems

1. Since this “greenhouse” problem is between only two countries, it might be resolved by some

international negotiation, or by levying a tax on all bread producers (including those in Leinster) and

using the proceeds to develop new filters for bakeries or new gas-free yeast strains.

2. Assuming that the pollution produced is domestic (rather than trans-border), migration of these

industries to other countries could increase world welfare if the perceived marginal social cost of

pollution in the richer countries exceeds the perceived marginal social cost of pollution in poorer

countries. Migration will also be welfare-increasing if the decreased production in the richer

countries causes a smaller absolute reduction in utility (because incomes are already high) than the

increase in utility associated with expanded production in poorer countries (because incomes are so

low).

3. The tax will increase the price of owning a telephone in Leinster, reducing domestic demand. As a

result, there will be an excess supply of telephones in the country, leading to more units available for

export to Saxony. Prices of imported phones will fall in Saxony, increasing national welfare as

consumer gains exceed local producer losses.

However, a broader measure of welfare in Saxony should include any external effects of increasing

telephone communication there. We could imagine a number of possibilities, including two of

opposite sign. In one scenario, Saxony could experience the same kind of negative externality that

Leinster was facing when its citizens were using their telephones and avoiding social interplay. On

the other hand, if Saxons are a dispersed, agricultural populace, increased access to telephones could

improve levels of communication across the country. This positive external effect would be well

served by increased imports of Leinster’s telephones. (In fact, the Leinsterian tax might end up

raising welfare significantly in “the world” as a whole by causing import-export patterns to better

reflect social measures of tastes.)

4. First, insofar as trade increases per capita incomes, the demand for a cleaner environment will

increase. Second, if diffusion of technology follows greater openness, developing countries are likely

to gain access to cleaner methods of production developed in industrialized countries. Finally, if

trade liberalization is accompanied by the removal of government protection of producers, we may

see less over-fertilization in developed countries’ agriculture, and less overuse of energy in the

nationalized industries in developing or transition economies.

5. There are a number of these “debt-for-nature” swaps already in existence, such as the United States’

Tropical Forest Conservation Act. Both sides in the swap benefit: lending countries get something

that otherwise might be difficult to obtain (preservation of biodiversity); borrowing countries get

debt relief, and the funds that otherwise would have gone out to pay international debts now stay at

home in the form of conservation activities.

Chapter 14

True/False

1. False: remember that “developed” refers to variables other than simply wealth or income.

2. False: they can be quite different.

3. True.

4. False: just as in the “optimal tariff,” world welfare is reduced by cartels.

5. True: as with taking off a Band-Aid, the record shows a short but sharp removal of controls is less

painful for transition economies. Although output levels will decline dramatically at first, GDP

recovers relatively quickly. Poland, for example, used shock therapy in 1990 but had resumed real

growth by 1992; the country is now a full member of the WTO and the EU. In contrast, Russia

liberalized more slowly starting in 1992 and did not see a return to real GDP growth until after 1996.

26

Multiple Choice

1. B

2. B

3. D

4. D

5. B

Problems

1. a. Among other reasons, the Saxon government could talk about the strategic importance of

telecommunications equipment and the spillover benefits gained from a light industry sector.

Saxony might also want to reduce its reliance on trade in bread since Engel’s Law suggests that

food producers stand to lose in a world of increasing incomes (the income elasticity of demand

for food is less than one). Arguments against industrialization include negative externalities of

urban-industrial areas, loss of traditional occupations in farming, and the chance that the “infant

industry” never matures.

b. A subsidy to Saxon telephone manufacturers would be a better idea than a tariff or a quota since

Saxony could avoid the consumption deadweight loss. A subsidy assumes, however, that the

Saxon government’s coffers have enough in them to fund the subsidy.

2. Recall Engel’s Law relies on an assertion that “food” is a staple and has an income elasticity of less

than one. When incomes rise, demand shifts towards luxuries (that have an income elasticity greater

than one) and away from staples. But what if the Ministry of Agriculture in Saxony developed a

program to move resources out of basic bread production and into more “luxury” foods, such as

exotic fruits and vegetables? Then, as incomes rise in both countries, the Saxon farmers would see

their prices and sales increasing.

3. Raw rubber is subject to a declining price, largely because of the development of synthetic

substitutes. On the other hand, it seems clear that worldwide demand for surgical supplies will grow:

the income elasticity of health care is probably greater than one. So on price grounds alone, it would

be wise for Malaysia to move away from exporting the primary product of rubber and toward the

manufacture of rubber-based goods. In addition, one could argue that the spillover benefits from light

manufacturing are likely to be far larger than those resulting from the extraction of raw rubber.

Possible policies to promote the development of a surgical goods industry are export subsidies for

those goods, or government support for research and development into the production of those goods.

(A problem for each of these policies, of course, is the limited size of the Malaysian government’s

revenues.)

4. Given d = –0.5, SO = 1.0 and c = 0.5, the optimal cartel markup t* = c / [d – SO (1 – c) ] = 50%.

Chapter 15

True/False

1. True.

2. False: FDI usually includes a large component of “human capital” such as management skills and

entrepreneurship.

3. True: their wages tend to rise as the domestic labor supply decreases.

4. True: the taxes paid by those workers are correlated with the level of their skills and wages.

5. True!

27

Multiple Choice

1. D

2. A

3. B

4. C

5. A

Problems

1. a. Since we have talked about the possibility of trade barriers, perhaps Leinster’s telephone

executives want to avoid being caught in a trade war.

b. FDI would be preferable if the profitable manufacture and distribution of telephones in Saxony

requires skills and assets that are unique to Leinster. Telecommunications equipment is typical of

the kinds of goods that are produced with firm-specific advantages.

c. The Leinster government would certainly want to warn telephone executives about the possibility

of political instability in Saxony, and the resulting likelihood that a manufacturing plant there

could be seized and nationalized. Leinster’s government might actually try to prevent this FDI if

the executives were moving their plant to Saxony simply to evade taxes in Leinster. And,

importantly, workers in Leinster (who otherwise would have been employed in the telephone

industry) will not be pleased about their jobs being “shipped overseas.”

d. The Saxon government will actively seek the employment and tax proceeds that would come

from hosting a new telephone plant, even if it is controlled by foreign owners. If there are

positive spillover benefits for the Saxon economy, the FDI will also be attractive. However, to

the extent that the Leinster telephone executives start to throw their weight around the Saxon

political arena, the FDI could turn out to be a Trojan horse.

2. You might see two different forces at work here. First, insofar as the cost of transporting finished

goods between countries is prohibitive, a foreign corporation might find it cost-effective to

manufacture goods in the host country for sale in that country. FDI would then decline as these sorts

of transportation costs were reduced.

On the other hand, when we consider the costs of transporting people and information, a reduction in

those costs would make it much easier for a corporation to maintain long-distance control over dayto-day operations of its foreign subsidiary. FDI would rise as a result.

3. a. In the absence of immigration, the wage in each country would reach equilibrium where the

quantity of labor demanded just equaled the quantity of labor supplied at that wage. Looking at

the graphs, you can see that this occurs at a wage of 10 scudos in Leinster and 14 scudos in

Saxony.

b. If labor has the possibility of moving between countries, workers from Leinster are sure to seek

the higher wages available in Saxony. This will tend to raise wages in Leinster (as the local

supply of labor declines) and to reduce wages in Saxony (as the local supply of labor rises).

c. i. If the flow of labor from Leinster to Saxony is restricted, wages will rise in Saxony and fall

in Leinster.

ii. “Stay behind” workers in Leinster will lose as their wages fall with the return of the

immigrants. “Stay behind” workers in Saxony, however, will gain as Leinsterian immigrants

leave the labor market. The immigrants themselves are clear losers—presumably, the reason

they emigrated in the first place was to improve their economic welfare.

iii. Leinster’s employers will gain as wages are bid back down again. Saxon employers will lose

as wages are bid back up again. Any employer who counted on immigrant workers will

definitely lose.

28

iv. The loss of welfare to the world as a whole can be illustrated by the two small triangles

bounded by the countries’ curves and the 12 scudo wage line on Figure 15.3.

4. Because farm labor is largely unskilled, the guest worker program fits a kind of specificity rule.

Increased immigration quotas would not guarantee that the extra immigrants are agricultural workers;

at least some are likely to be “brain drain” immigrants who would not (and, in a sense, should not)

work in agriculture.

Second, guest workers are usually given only temporary labor permits. In this way, after the labor

needs of the harvest, these immigrants would be required to exit the country. Cyclical labor demands

would be exactly matched by cyclical labor supplies.

Finally, in contrast to many undocumented immigrants, the guest workers’ wages would be taxed,

and so the immigrants would be much less likely to represent a fiscal burden to the host country.

5. This is a bit of factor price equalization on its head. Instead of commodities moving, the factors that

produce them do. Instead of equating commodity prices on the way to equating factor prices, we

might just have factors of production move between countries until the income each kind of factor

can earn is equated internationally.

Chapter 16

True/False

1. False: a net debtor is a country that has had mostly negative net foreign investment in the past, not

necessarily this year.

2. True.

3. False.

4. True: since Y = C + I + G + (X – M), when G increases, (X – M) must decrease.

5. Perhaps!

Multiple Choice

1. A

2. B

3. D

4. C

5. A

Problems

1. a. We know that Y = C + Id +G + (X – M), so for Leinster, 100 = 60 + 15 + 15 + (20 – M). Imports

(M) from Saxony are 10 billion lira.

b. Since Leinster is running a trade surplus with Saxony (exports from Leinster exceed imports into

Leinster by 10 billion lira), Leinster is “lending” to Saxony. Saxony pays for the extra imported

telephones by sending Leinster an IOU or by giving Leinster title to assets worth 10 billion lira.

2. a. The cottage purchase is a debit on the financial account.

The baseball bats are a credit on the current account.

The profits are a credit on the current account.

The interest paid is a debit on the current account.

The remittance to Dublin is a debit on the current account.

The Las Vegas fling is a credit on the current account.

The hot dog stand purchase is a credit on the financial account.

29

The purchase of wine is a debit on the current account.

b. The balance on goods and services is (credits of $2,004) – (debits of $1,002) = a trade surplus of

$1,002.

The balance on the current account includes the balance on goods and services as well as net

income and unilateral transfers. Here, net income = (Costa Rican profits – Treasury interest paid)

and unilateral transfers (the remittance to Dublin). So the overall current account balance is

(+$1,002) + (–$2) + (–$996) = $4.

In this case, both of the listed capital flows are direct investment. Net private capital flows equal

(the Greek’s purchase of a NYC hot dog stand) – (Trump’s purchase of a French cottage) = –$2.

c. Because

CA + FA + OR = O,

we know that OR = – (CA + FA)

so

OR = – ($4 – $2) = –$2.

This means that the Federal Reserve must be buying $2 worth of foreign currency.

d. Since this is a very small change in official reserves, it is unlikely that the Fed is engaging in

some scheme to fix the value of the currency.

3. The only credit item for the current account is (c) the sale of weapons to the Israelis.

4. a. The merchandise trade balance = (electronic goods exports) – (food imports) = –$200.00

The current account balance = merchandise trade balance + (service exports – service imports)

= –$200 + (computer consulting – vacations abroad)

= –$200 + ($1,600 – $200)

= $1,200.00

(Notice that the current account is in surplus—despite a merchandise trade deficit—thanks to a

big surplus on services.)

b. Because the current account is in surplus, Avalon must be increasing its net holdings of foreign

assets. This is clearly the case: capital outflows to buy Saxon summer homes ($500) and shares

in a telephone firm in Leinster ($800) exceed capital inflows to buy Avalon corporate bonds

($100). The balance on the financial account is –$1,200 and this exactly equals the balance on

the current account ($1,200).

c. Because Avalon had positive foreign investment abroad in 2011 does not mean that the country

is a net creditor. Whether a country is a net creditor or debtor depends on the entire spectrum of

capital flows over the country’s history. In the past, Avalon may have run massive current

account deficits and so amassed a great deal of overseas debt. The net capital outflow of 2011

alone would probably not negate this accumulated debt.

5. No. The “twinning” of the budget and trade deficits in the U.S. reflected, at least in part, low private

saving rates. Domestic investment and government spending exceeded the amount of saving by

American residents; households were on a spending spree too. As a result, the quantity demanded of

output was greater than our own production. The result was a need to import goods and services from

abroad. So, we could have looked at the 1980s as a period of low saving “twinned” with a trade

deficit.

A useful contrast is the case of Japan during the same period, when the Japanese government was

running a budget deficit but the country was running a trade surplus. In this case, saving rates of

residents were so high that they provided not only for domestic investment and government

expenditure, but for America’s needs as well.

30

Chapter 17

True/False

1. False: to purchase the imports, we supply dollars in exchange for francs.

2. False: intervention is more prevalent under pegged rates.

3. True.

4. True (unless you are Swiss and are bidding at Sotheby’s!)

5. True.

Multiple Choice

1. C

2. B

3. B

4. C

5. A

Problems

1. a. The equilibrium exchange rate is 100 scudos per lira, or Ss 100/Ll.

b. Since this is a nominal “bilateral” exchange rate, just invert it (or yourself) to find that the

exchange rate from Leinster’s point of view is 0.01 Ll/Ss.

c. You would expect the supply of lira in exchange for scudos to increase, shifting the supply curve

to the right and pushing the exchange rate down. So it would take fewer scudos to buy a lira, or a

lira would not exchange for as many scudos. This is an appreciation of the scudo and a

depreciation of the lira.

d. If the minister had wanted to keep the exchange rate at Ss 100/Ll, she would have to satisfy the

excess demand for scudos that would arise when the supply of lira increased. (In fixed exchange

rate terminology, the scudo would be undervalued at the old exchange rate of Ss 100/Ll.) This

would require the Saxon minister of finance to sell scudos and buy up lira.

2. a. Keep in mind throughout this problem that an appreciation of the scudo means it costs more lira

to buy one scudo (or that it takes fewer scudo to purchase one lira).

Because it will take more lira to buy the scudo, the Saxon goods denominated in scudo will be

more expensive for someone in Leinster to purchase.

b. The Saxon goods will now bring in more lira than before. Unfortunately, the increase in the price

of those goods to Leinster residents may mean that fewer Saxon goods are purchased by

Leinster’s residents than before.

c. The Leinsterian goods will now bring in fewer scudo than before. The upside to this is that

Saxons see Leinster’s goods becoming cheaper and may purchase more of them.

d. If the retiree is a Saxon, the appreciation of the scudo means she can buy more Leinsterian goods

than before, although it won’t change her ability to purchase domestic goods. If the retiree lives

in Leinster, she has protected her ability to purchase imports, and if she cashes the scudo in for

lira, she will get many more lira than before.

e. If those who expected a depreciation of the lira had sold them all for scudos, the appreciation of

the scudo (that is, the depreciation of the lira) will turn out to have been a very good thing. Their

scudos are now worth many more lira.

31

3

a. Since the supply of euros would fall, we would expect the $/€ exchange rate to rise: the euro

would appreciate and the dollar would depreciate.

b. The American demand for euros would rise, so the exchange rate would rise: the euro would

appreciate and the dollar would depreciate.

c. The American demand for euros would rise, so the euro would appreciate and the dollar would

depreciate.

d. The French supply of euros would rise, so the euro would depreciate and the dollar would

appreciate.

e. The American demand for euros will fall as American speculators dump the euro, and the

exchange rate would fall, too: the euro would depreciate, in a “self-fulfilling prophecy.”

4. a. The U.S. must sell euros and buy dollars to keep the dollar from depreciating.

b. As in 4.a., the U.S. must sell euros and buy dollars to keep the dollar from depreciating.

c. Once again, the U.S. must sell euros and buy dollars.

d. The U.S. must buy euros and sell dollars to keep the dollar from appreciating.

e. The U.S. must buy euros and sell dollars to keep the dollar from appreciating.

5. The “route to follow” would be Tokyo yen to New York dollars to Munich euros to Tokyo yen.

In Tokyo: take the million yen and trade them for dollars, receiving $10,000.

In New York: take the $10,000 and trade them for euros, receiving €30,000.

In Munich: take the €30,000 and trade them for yen, receiving Y2.1 million.

You would end up with a profit of 1.1 million yen for being so observant and taking advantage of

triangular arbitrage.

Chapter 18

True/False

1. False: the forward rate may approximate what investors think the future spot rate will be, but it will

not determine the actual future spot rate.

2. False: speculation may occur through both short and long positions.

3. True.

4. False, at least insofar as you can see many flattened hedgehogs along the roads in England.

5. True.

Multiple Choice

1. B

2. A

3. C

4. B

5. D

Problems

1 a. If you sell lira forward (buy scudos forward) you will receive 95 scudos for each of the 10,000

lira, for a total of Ss 950,000.

b. If your high guess about the future spot rate (Ss 105/Ll) turns out to be correct, when you sell

your 10,000 lira you will receive a total of Ss 1.05 million instead of the guaranteed Ss 950,000

from a forward contract. But if the future spot rate turns out to be on the low side, you will get

only Ss 850,000.

32

c. How much risk do you like in your life? Will you have to work in the bakery the rest of your life

to make up the Ss 100,000 you lost? Just how understanding are your parents?

2. a. To start off this question, you want to express interest rates and exchange rates in the same

periodicity. So convert the annual interest rates into semi-annual (180-day) rates by dividing by

2: the 180-day interest rate in Saxony is 4%; the 180-day rate in Leinster is 3%.

To figure out whether financial capital will flow between the countries, we want to compare the

risk-free returns Saxons can earn at home and abroad, and the risk-free returns Leinsterians can

earn at home and abroad. This means we need to look not only at the interest rates offered but at

what, if any, exchange rate gains or losses may be incurred.