CCLE Conference Workbook

advertisement

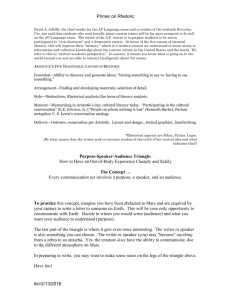

A Primer On Dialectic and Rhetoric for Classical Educators by Jim Tallmon, Ph.D. Director of Debate Professor of Rhetoric Patrick Henry College jmtallmon@phc.edu Prepared for the Consortium of Classical and Lutheran Education Annual conference Concordia, MO 22-24 June, 2010 © 2009 1 In the restored man dialectic and rhetoric will go along hand in hand as the regime of the human faculties intended that they should do. –Richard M. Weaver, Language is Sermonic Wisdom and Eloquence = Dialectic and Rhetoric Aristotle’s opening line from his Rhetoric: “Now rhetoric is a counterpart (antistrophos) of dialectic.” Later, he relates rhetoric to ethics. Implications regarding Truth, Beauty, and Goodness So, how does one teach them side-by-side? Within the context of Argumentation & Debate, I emphasize that, in order to be truly persuasive one’s analysis of opposing views must penetrate the surface. “Bootcamp of the Mind” Tallmon on practical reasoning: Cultivating the intellectual abilities to . . . 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Follow an argument to its conclusion. Identify and evaluate assumptions. Spot faulty logic and contradictions. Make appropriate distinctions. Avoid extremes. Exercise foresight. Three Tools SO--HOW DOES ONE IDENTIFY ASSUMPTIONS? Art vs. Intuition Syllogistic Logic: A little knowledge about syllogisms gives one a means of identifying assumptions. Richard M. Weaver's Rhetoric and Handbook, Chapter 5, is excellent here. It's my primary source. http://www.phc.edu/rr_logictutorial.php In the traditional liberal arts education, (as pre-teens) kids were taught how to follow an argument by learning syllogisms. Categorical syllogisms are the easiest kind to understand. Make it child’s play! Measured doses . . . An enthymeme is a syllogism with one of the propositions missing. WHY IS THAT IMPORTANT? 2 Weaver answers: "Since a great many of the world's arguments appear in the form of enthymemes, it is of great value to acquire some facility in expanding the enthymeme into a complete syllogism. Then, whether or not we shall be persuaded by the argument will depend upon whether or not we accept both of the premises. And even if we can accept both of the premises, we must be able to see whether the conclusion emerges in accordance with the formal rules of the syllogism." Some exercises: “Minding the premises,” “Pass the remote,” etc. Now we know how to identify an assumption. What do you do with an assumption once you get a hold of one?? Dialectic and Common Material Fallacies are tests for truth. http://www.phc.edu/rr_commonfallaciesexercise.php (Validity vs. Truth) Dialectic: Aristotelian dialectic is not to be confused with Hegelian dialectic! May be understood as a three-step process whereby one tests for the truth of propositions of a contingent nature: TESTS FOR TRUTH A. Begin with an assumption. (proposition, assertion, statement, etc. ) B. Push it to its logical conclusion, drawing out implications. (Key questions) C. Apply the law of contradiction.--Metaphysics: 1011b: Aristotle: "the most undisputable of all beliefs is that contradictory statements are not at the same time true." Aristotle’s Topica is explicitly concerned with formalizing the first set of rules for disputations and the label, “dialectician” is ascribed almost exclusively to competitors in mental gymnastics. Aristotle’s final exhortation to the would-be disputant indicates a higher concern than mere competition: “Moreover, as contributing to knowledge and to philosophic wisdom the power of discerning and holding in one view the results of either of two hypotheses is no mean instrument; for it only remains to make a right choice of one of them”(Topics 163b 9). Aristotle maintains the distinction between dialectical disputation and dialectical inquiry throughout his Topics. Dialectic should be understood also as “A process of criticism wherein lies the path to the principles of all inquiries” (Topics, 101b 4). Dialectic is exemplified in the Socratic method. It is, in its essence, a test for truth, founded on the law of contradiction. Another way to understand dialectic is as a tool for securing propositions. If any single function captures the essence of dialectic as a test for truth, it is the securing of propositions. Propositions are not secured during the course of disputation; that is a matter of reasoning which should take place prior to argument. A proposition is dialectically secured when it passes the muster of the “most undisputable of all beliefs”: the law of contradiction. Therefore, securing propositions is dialectic reduced to its purest function. Richard Weaver has a number of fine essays on the relationship between rhetoric and dialectic. Following, for example, is an excerpt, taken from a single essay, "The Phaedrus and the Nature of Rhetoric," in The Ethics of Rhetoric: 3 Now rhetoric as we have discussed it in relation to the lovers consists of truth plus its artful presentation and for this reason it becomes necessary to say something more about the natural order of dialectic and rhetoric. In any general characterization rhetoric will include dialectic, but for the study of method it is necessary to separate the two. Dialectic is a method of investigation whose object is the establishment of truth about doubtful propositions. . . . With its forecast of the actual possibility, rhetoric passes from mere scientific demonstration of an idea to its relation to prudential conduct. A dialectic must take place in vacuo, and the fact alone that it contains contraries leaves it an intellectual thing. Rhetoric, on the other hand, always espouses one of the contraries. This espousal is followed by some attempt at impingement upon actuality. That is why rhetoric, with its passion for the actual, is more complete than mere dialectic with its dry understanding. It is more complete on the premise that man is a creature of passion who must live out that passion in the world. Pure contemplation does not suffice for this end. As Jacques Maritain has expressed it: "love . . . is not directed at possibilities or pure essences; it is directed at what exists; one does not love possibilities, one loves that which exists or is destined to exist." The complete man, then, is the “lover” added to the scientist; the rhetorician to the dialectician. Understanding followed by actualization seems to be the order of creation, and there is no need for the role of rhetoric to be misconceived. … The pure dialectician is left in the theoretical position of the non-lover, who can attain understanding but who cannot add impulse to truth (21). (For further reading, please see Richard M. Weaver’s: "The Cultural Role of Rhetoric," "Language is Sermonic," “The Phaedrus and the Nature of Rhetoric" and "The Importance of Cultural Freedom" at “Weaver’s Top Ten” on http://www.RhetoricRing.com It is important to impart this knowledge in stages. It is best to dispense the concepts as the student walks through a number of assignments that give opportunities for practical application. "Stair step" the learning, and remember that rhetoric is a practical art, not a subject matter (see Aristotle's Rhetoric, Book I, Chpt. 1). Remember the trivium are tools of learning! Philosophical Speech Forensic Argumentation Moral Argumentation Policy Debate 4 Rhetoric, Pathos and Style Aristotle's Definition of rhetoric: “The faculty of discovering in any given case the available means of persuasion.” Ethos Three Modes of Artistic Proof: Pathos Logos Rhetoric appeals to human beings in their fullness. One may be convinced by logical appeals, but to really persuade, to move an audience, one must appeal to core values and emotions. See RhetoricRing.com’s Speech Builders Emporium Sir Francis Bacon's definition of rhetoric: "The application of reason to imagination for the better moving of the will." Making one's arguments aesthetically pleasing is important, if for no other reason, than that it exercises imagination (both the speaker's and the audience's.) Logic gives arguments strength and weight, but images give arguments impact! In the traditional liberal arts education, style was learnt by studying figures of speech. Figures of speech are divided into: Schemes (syntactic) | rhythm Tropes (Semantic) | imagery 5 Discuss exercises and imitatio (Two examples: Small Catechism & I Jn 1) return to Weaver. The Ethics of teaching rhetoric and dialectic this way. AND why it equips our kids to think like Lutherans (conclusion of my LW piece & Kopff’s comment). RESOURCES Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. Introduction to Aristotle. Richard McKeon. ed. New York: Modern Library, 1947. _________. Nicomachean Ethics. Terence Irwin. trans. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1985. _________. On Rhetoric. George Kennedy. trans. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1991. _________. Posterior Analytics. Hugh Tredennick. trans. The Loeb Classical Library. G. P. Goold ed. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1926. _________. Prior Analytics. Translated by A. J. Jenkinson, In The Great Books of the Western World edited by Robert M. Hutchins and Mortimer J. Adler. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 1952. _________. Rhetoric. J.H. Freese. trans. The Loeb Classical Library. G. P. Goold ed. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1926. _________. Rhetoric. Translated by W. Rhys Roberts, in Aristotle: Rhetoric and Poetics, Friedrich Solmsen, ed. New York: Modern Library, 1954. _________.Topics. Translated by W. A. Pickard-Cambridge, in The Great Books of the Western World , edited by Robert M. Hutchins and Mortimer J. Adler. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 1952. Bacon, Francis. Advancement of Learning. The Great Books of the Western World. Robert M. Hutchins and Mortimer J. Adler eds. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1952. Bitzer, Lloyd and Edwin Black, eds. The Prospect of Rhetoric. Eglewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1971. Bizzell, Patricia and Bruce Herzberg. eds. The Rhetorical Tradition. New York: Bedford Books, 1990. Booth, Wayne C. The Knowledge Most Worth Having. U Chicago Press, 1967. _________. The Vocation of a Teacher. Chicago: U Chicago Press, 1988. Brockriede, Wayne. “Arguers as Lovers.” Philosophy and Rhetoric 5 (1972): 1-11. Campbell, John A. “Darwin, Thales and the Milkmaid.” Perspectives on Argumentation, 6 Robert Trapp and Janice Schuetz, eds. (Waveland Press, 1990), 207-20. Cicero. De Inventione. H. M. Hubbell. trans. The Loeb Classical Library. T. E. Page. ed. Cambridge: Harvard U P, 1960. _________. Topica. H. M. Hubbell. trans. The Loeb Classical Library. T. E. Page, ed. Cambridge: Harvard U P, 1960. _________. De Oratore. J. S. Watson. trans. Cicero on Oratory and Orators. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois U P, 1970. Conley, Thomas M. Rhetoric in the European Tradition. New York: Longman, 1990. Dieter, Otto Alvin Loeb. “Stasis.” Speech Monographs 17 (1950): 345-69. Dunne, Joseph. Back to the Rough Ground: ‘Phronesis’ and ‘Techne’ in Modern Philosophy and in Aristotle. Notre Dame: U Notre Dame P, 1993. Farrell, Thomas B. Norms of Rhetorical Culture. New Haven: Yale U P, 1993. Golden, James L. and Joseph J. Pilotta eds. Practical Reasoning in Human Affairs. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Company, 1986. Jonsen, Albert R. and Stephen Toulmin. The Abuse of Casuistry. Berkeley: U California Press, 1988. Jost, Walter. Rhetorical Thought in John Henry Newman. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1989. _________. “Teaching the Topics: Character, Rhetoric, and Liberal Education.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 21 (1991): 1-16. Kennedy, George A. Classical Rhetoric and Its Christian and Secular Tradition From Ancient to Modern Times. Chapel Hill: U North Carolina Press, 1980. Leff, Michael. “The Topics of Argumentative Invention in Latin Rhetorical Theory from Cicero to Boethius.”Rhetorica 1 (1983): 23-44. McKeon, Richard. Rhetoric. Woodbridge, CT: Ox Bow Press, 1987. _________. “Creativity and the Commonplace.” Philosophy and Rhetoric 6 (1973): 199210. Miller, Carolyn R. “Aristotle’s ‘Special Topics’ in Rhetorical Practice and Pedagogy.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 17 (1987): 61-70. Moss, Jean Deitz. ed. Rhetoric and Praxis: The Contribution of Classical Rhetoric to Practical Reasoning. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic U of America Press, 1986. 7 Murphy, James J. ed. Medieval Eloquence. Berkeley: U of California P, 1978. Natanson, Maurice and Henry W. Johnstone, Jr. eds. Philosophy, Rhetoric and Argumentation. University Park: Pennsylvania State U Press, 1965. Nelson, John S., Allan Megill, and Donald N. McCloskey, eds. The Rhetoric of the Human Sciences. Madison: U Wisconsin Press, 1987. John Henry Newman. An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent. Notre Dame: U Notre Dame P, 1979. Olmsted, Wendy Raudenbush. “The Uses of Rhetoric: Indeterminacy in Legal Reasoning, Practical Thinking and the Interpretation of Literary Figures.” Philosophy and Rhetoric 24 (1991): 1-24. Perelman, Chaim. “The New Rhetoric: A Theory of Practical Reasoning.” The Great Ideas Today. Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., 1970, 272-312. _________.The New Rhetoric and the Humanities. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Co., 1979. _________. The Realm of Rhetoric. Notre Dame: U Notre Dame Press, 1982. Prelli, Lawrence J. A Rhetoric of Science: Inventing Scientific Discourse. Columbia: U South Carolina P, 1989. Price, Robert. “Some Antistrophes to the Rhetoric.” Philosophy and Rhetoric 1 (1968): 145-64. Richards, I. A. The Philosophy of Rhetoric. London: Oxford UP, 1936. Rycenga, John A. and Schwartz, Joseph, eds. The Province of Rhetoric. New York: Ronald Press, 1965. Simons, Herbert W. ed. The Rhetorical Turn. Chicago: U Chicago Press, 1990. Sloane, Thomas O. ed. The Encyclopedia of Rhetoric. Oxford University Press, 2001. Stump, Eleonore. Boethius’s De topicis differentiis. Ithaca: Cornell U P, 1978. _________. Boethius’s In Ciceronis Topica. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1988. Tallmon, James M. “Casuistry and the Role of Rhetorical Reason in Ethical Inquiry,” Philosophy and Rhetoric 28 (1995): 377-87. _________. "How Jonsen Really Views Casuistry: A Note on The Abuse of Father Wildes.” The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 13 (1994): 103-13. 8 _________. “Newman’s Contribution to Conceptualizing Rhetorical Reason,” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 25 (1995): 197-213. Trapp, Robert and Janice Schuetz. eds. Perspectives on Argumentation. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, 1990. Warnick, Barbara. “Judgment, Probability, and Aristotle’s Rhetoric.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 9 (1989): 299-311. Weaver, Richard. Ethics of Rhetoric. Davis, CA: Hermagoras Press. 1985 _________. Ideas Have Consequences. U Chicago Press, 1948. (Now available from the Intercollegiate Studies Institute.) _________. Language is Sermonic. Louisiana State U P, 1970. _________. A Rhetoric and Handbook. Holt, Rhinehart and Winston, 1967. _________. Visions of Order: The Cultural Crisis of Our Time. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State U P, 1964. (Now available from the Intercollegiate Studies Institute.)