J. Geffen

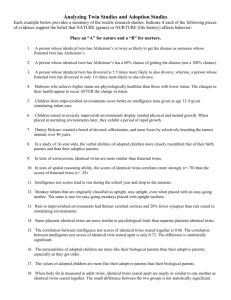

advertisement

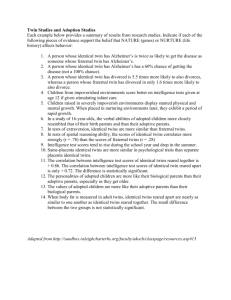

Whenever the Twain Shall Meet By: T.J. Bouchard From: The Sciences, September/October, 1997 J. Geffen 5 10 15 20 25 30 1. They arrived at the Minneapolis airport from opposite ends of the United States. Although they had only spoken on the phone a few times, they hugged, laughed and cried when they met. As they walked down the airport corridor to the baggage claim, I followed along, struck by the remarkable similarity in the pace of their speech. As soon as one stopped talking the other would start, like a pair of jugglers passing oranges to and fro, and yet the conversation never seemed to stumble or fall out of sync. My wife and I had been married for well over twenty years, I remember thinking, and we could not carry off such a highly coordinated exchange. And the same was true of my conversations with two old, close friends. 2. I was astounded. It had never occurred to me that the pace and rhythm of speech might have a genetic basis. And yet the conclusion was inescapable, for these two people were identical twins, raised in separate homes, who were reuniting for the first time. “This is amazing,” one of them turned to tell me when we reached the baggage counter. “It’s as if we’ve known each other all our lives.” 3. In the past two decades I have heard those words time and again. As the founder of the Minnesota Center for Twin and Adoption Research at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, I have studied hundreds of pairs of twins, some of them fraternal, or dizygotic, some identical, or monozygotic, some raised in the same home, some separated at birth. The most striking of the pairs are identical twins who have been raised apart. Although identical twins are true human clones, born with exactly the same genes, their similarities are often ascribed to the fact that they are dressed the same, treated the same, escorted through childhood side by side. But twins who have grown up in different families deflate such arguments. They represent a crucial control in twin studies – an elegant tool for prying apart the relative effects of nature and nurture on psychological traits. 4. When we began our work, only twenty-five pairs of such twins had ever been reunited and studied in the United States. Today more than eighty pairs of identical twins and almost sixty pairs of fraternal twins reared apart have been studied in our program alone. They have submitted to dental X-rays, blood tests and psychiatric interviews, to medical examinations and fingerprinting, and to questionnaires and ability tests so exhaustive they take nearly fifty hours to complete. The resulting studies are indisputably important on scientific grounds alone, and they have an undeniable appeal to the public. But since the recent breakthrough in cloning, they have taken on an added significance. Whenever the Twain Shall Meet / 2 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 5. In literature, in films, and in some of the more hysterical accounts in the press, clones have been portrayed as anything from soulless automatons to evil doppelgängers. No one really knows how true clones would behave, such accounts suggest, so the imagination can have free rein. But the truth is, of course, that biological human clones have existed as long as humanity itself. And though twin studies have demonstrated the power of genes to shape psychological traits, they have also demonstrated the limits of that power. Any discussion of future clones, in other words, ought to begin by revisiting the clones already among us. 6. The scientific study of twins and their similarities and differences dates back to the nineteenth century and the work of the English polymath Sir Francis Galton. Although Galton held no formal position or degree, he was a brilliant explorer and thinker who invented fingerprinting, among other accomplishments. Galton never studied identical twins reared apart, but his work on twins reared together, adopted children and ordinary families, as well as the statistical tools he developed, helped lay the foundations of behavioral and biometrical genetics and eugenics. Charles Darwin, in his book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, cites one of Galton’s anecdotes: A gentleman of considerable position was found by his wife to have the curious trick, when he lay fast asleep on his back in bed, of raising his right arm slowly in front of his face, up to his forehead, and then dropping it with a jerk so that the wrist fell heavily on the bridge of his nose… Many years after his death, his son married a lady who had never heard of the family incident. She, however, observed precisely the same peculiarity in her husband; but his nose, from not being particularly prominent, has never as yet suffered from the blows…. One of his children, a girl, has inherited the same trick. 7. Similar stories are sometimes told about siblings or fraternal twins, but much more frequently about identical twins. In fact, the pair I mentioned earlier (whom we nicknamed the Talking Twins) are similar in an astonishing range of psychological traits, as are most other identical twins reared apart. A pair we nicknamed the Giggle Twins laughed more than anyone else they knew, never engaged in controversial talk or voted, and had a habit of pushing up their noses with their fingers. Another pair, alone among the hundreds studied, independently refused to enter an acoustically shielded room in our psychophysiology laboratory (both acquiesced when the door was wired open). Still another pair discovered they both used Vitalis hair tonic, Lucky Strike cigarettes, Vademecum toothpaste and Canoe shaving lotion. We have had two captains of volunteer fire departments, two gunsmith hobbyists, two women who would only enter the ocean backward and then just up to their knees, two men who left love notes around the house for their wives. 8. Some of those similarities are surely coincidental – complete strangers at cocktail parties routinely discover “astonishing” concurrences in their lives; imagine Whenever the Twain Shall Meet / 3 80 85 90 95 100 105 110 115 what they might find after fifty hours of filling out questionnaires. But some similarities are too idiosyncratic, too particular, to be dismissed as mere coincidence. The Necklace Twins, for instance, had the unconscious habit of slowly rotating the necklaces they were wearing while responding to interviewers, but not when they were simply listening. They both also tended to offer interminable answers to even simple questions. 9. On average, our questionnaires show that the personality traits of identical twins have a 50 percent correlation. The traits of fraternal twins, by contrast, have a correlation of 25 percent, non-twin siblings a correlation of 11 percent and strangers a correlation of close to zero. When identical twins are reared apart, their personality correlations must be an effect of genetics. By the same token, since the twins are genetically identical, their 50 percent dissimilarity must be caused by environmental influences and measurement errors (psychological tests are less reliable than most physical measurements). Seen on an electroencephalogram (EEG), the brain waves of identical twins are even more similar than our studies would suggest. Although EEGs are usually as distinct as fingerprints, the EEGs of identical twins are about as similar as two EEGs of the same person plotted at different times. 10. Equally remarkable is the fact that adult identical twins reared in the same family are no more similar than identical twins reared apart. In other words, if one of a pair of identical twins were raised in a family of academics, and the other were brought up in a blue-collar family by parents who only finished high school, the pair would be as similar at the age of thirty as if they had grown up in the same household. Such findings fly in the face of the emphasis on the role of the environment in child development that has pervaded American psychology until very recently. 11. And yet identical twins are much less similar to each other than many people would suppose. Consider the Talking Twins: one is gay and the other is straight. Like the rest of us, identical twins are shaped in part by their unique experiences. One of the Necklace Twins, for instance, was stricken by a severe case of polio as a child, and today she walks with a distinct limp. 12. Again and again, since the cloning of Dolly was announced, news reports have raised the specter of human clones who would be identical to their progenitors in every way. At first glance, the stories from our study may seem to reinforce that idea. But seen from another perspective, twin studies underscore rather than erase their subjects’ individuality. In spite of the unconscious urgings of their identical genomes, in spite of being raised together and schooled together, identical twins still respond differently to many of the items on our questionnaires. And those differences are only the tip of the iceberg. Beneath them flow shadowy memories and feelings, experiences and dreams that no investigator can sound, much less reproduce. Selves, unlike cells, can never be cloned. 13. If identity were merely a matter of genes, all human beings would be nearreplicas of one another – and so, for that matter, would all primates. Of the 100,000 Whenever the Twain Shall Meet / 4 120 125 130 135 140 145 150 155 genes that make up a person’s genome, nearly three quarters are identical in all humans, and of those all but a handful are identical to the genes of a gorilla. Known as monomorphic genes, they describe most of what is human. It is the remaining quarter of the human genome, made up of so-called polymorphic genes, that defines us as individuals. 14. At conception the human embryo receives half its genes from the father, half from the mother. Because monomorphic genes never vary, every child gets the same standard set, which is why every child looks recognizably human. But each of the more than 20,000 polymorphic genes can come in between two and more than twenty varieties. Hence the chance that two people will receive the same combination of polymorphic genes is virtually nil, with one exception. About once in every 300 births, for reasons not entirely clear, a fertilized egg splits in half, giving rise to identical twins, each of whom possesses exactly the same genome. (Fraternal twins, by contrast, are no more genetically similar than any other siblings; they come from distinct eggs fertilized by distinct sperm.) 15. Just how identical twins differ from other children in terms of their genetic inheritance is more complicated than it might appear. Some traits, such as blood type, are determined by one gene. Others, known as additive generic traits, are determined by the sum of the effects of a number of genes. A child who gets half his stature genes from a tall father and half from a short mother will end up medium-size. But if the father happens to contribute all of his genes for tallness, and the mother few of her genes for shortness, the child will be tall. As one might expect, identical twins are nearly always the same height (though a twin who is better nourished in or out of the womb might grow taller), whereas siblings and fraternal twins show, on average, only about a 50 percent correlation in height. 16. There are still other traits, however, that are not passed on proportionally. Known as nonadditive genetic traits, they depend on combinations of genes as interdependent as telephone numbers: miss one digit and they dial a different person. A body’s histocompatibility code – the unique set of proteins that marks each of its cells – is one example: change a single histocompatibility protein on, say, a kidney cell, and the immune system will reject it as foreign. Beauty is another: take Liam Neeson’s nose and put it on Uma Thurman’s face, and she probably will not be cast as Aphrodite again. 17. Every month, it seems, new reports emerge about specific genes identified for various personality traits – the alcoholism gene, the manic-depression gene, the novelty-seeking gene. But few have stood up to closer inspection. Clearly, the genetic components of many complex traits are nonadditive. And yet only ten years ago nonadditive traits were ignored in the domain of personality, largely because they were impossible to measure. 18. Extended kinship studies and large twin studies such as ours have changed that. Because identical twins inherit all of the same genes, they are far more likely to share Whenever the Twain Shall Meet / 5 160 165 170 175 180 185 190 195 nonadditive traits than other siblings are. (The rule of thumb is that traits more than twice as common in identical twins than in fraternal twins are likely to be nonadditive.) As recently as 1989, a review of the genetic literature on behavioral traits concluded that “religiosity and certain political beliefs … show no genetic influence.” But our studies show just the opposite: identical twins reared apart are more than twice as similar in their religious interests and values than fraternal twins reared apart, suggesting that religiosity may be a nonadditive trait. The same is true of a penchant for arts and crafts and a wide range of other interests. 19. Any discussion of genetic inheritance, no matter how straightforward, inevitably hits a sticking point: Psychologists and educators might be willing to concede that an interest in arts and crafts can be inherited, but ideas about the genetic influence on intelligence are freighted with too much unsavory history – with eugenics and racism and ruthless social policy – to pass uncontested. And so educational reports still favor the so-called average-child hypothesis (the belief that all children are basically equivalent in their capacity to learn and develop), and some psychologists dismiss intelligence as an arbitrary category, impossible to define objectively, much less inherit. In the words of the psychologist Leon J. Kamin of Northeastern University in Boston, written more than twenty years ago but still cited by textbooks: “There exists no data which should lead a prudent man to accept the hypothesis that I.Q. test scores are in any degree heritable.” 20. Studies of genetic influence are, according to some critics, ancestors of an old, reductionist view known as Galton’s error. Galton apparently borrowed the phrase “nature and nurture” from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, in which Prospero calls Caliban “a devil, a born devil, on whose nature/Nurture can never stick; on whom my pains,/Humanely taken, all, all lost, quite lost.” Findings from twin studies, critics say, are equally simplistic. 21. The truth is, however, that behavioral genetics theory can explain everything that socialization can explain, only better – and with statistics and reproducible results attached. Kamin’s comments notwithstanding, there is a strong consensus among knowledgeable experts in psychology, sociology, cognitive science and behavioral genetics that IQ is heritable. In fact, it is the single most heritable trait of all the traits studied by programs such as ours. 22. How can we be so certain, especially about a subject so prone to misinterpretation? The answer is that identical twins reared apart are nearly ideal study subjects – as close to an inbred strain of mice as the human behavioral geneticist can hope to find. Such twins represent an experiment of nature (twinning) and an experiment of nurture (adoption). Their psychological traits correlate so highly with one another that a study of fifty pairs of twins reared apart can often tell as much about heritability as one conducted on 1,000 pairs of twins raised together. 23. Identical twins raised apart are more similar, in almost every physical and psychological trait, than fraternal twins raised together. What better proof that our Whenever the Twain Shall Meet / 6 200 205 210 215 220 225 230 235 genes shape us at least as much as our environment? True, small adoption studies in France have shown that socioeconomic status can influence a child’s I.Q. But such influences tend to fade entirely by adulthood – as comparisons of results from studies of young with studies of older twins have shown. One of our own studies offered a vivid example of how genetic predisposition comes to the fore. When we asked identical twins to track a rotating target with a stylus, they often began by performing at different skill levels. Eventually, though, their scores became quite similar. Fraternal twins, on the other hand, tended to attain and then maintain different skill levels, even after three days of practice. 24. The study of intelligence seems to crystallize such similarities. Twin studies of various kinds consistently find that intelligence is between 60 and 70 percent heritable – in other words, between 60 and 70 percent of the variance in intelligence is due to genetic factors. In June the journal Science published a study of 110 pairs of identical twins reared together and 130 pairs of fraternal twins reared together, all of them eighty or more years old and living in Sweden. On average, the investigators found, heredity accounted for 62 percent of the variance in general cognitive ability among the twins. 25. Many psychologists maintain that nurture does more than nature does to shape intelligence. But in that case, unrelated adults who have been reared together (when one is adopted, for instance) ought to have similar IQ scores. In fact, the opposite is true: even after growing up in the same home, unrelated adults are no more alike in intelligence than complete strangers. 26. For all their striking findings, twin studies do not explain how genes influence personality, intelligence or social attitudes. In any case, few behavioral geneticists think that genes determine behavior directly. Rather, genes make a given body or personality more likely to respond to its environment in certain ways. Identical twins who are strong, sociable and well coordinated, for instance, are both likely to become interested in team sports. But that hardly equates to a “team sport gene.” 27. It is important to realize that people tend to create their own environments. Given a sufficiently supportive environment with varied opportunities, individuals choose and interact with surroundings that match their genotypes. A person predisposed to religion, in other words, is likely to find her way into the company of other religious people, even if her parents are confirmed atheists. At the same time, there are limits to what one can make of one’s surroundings. Just as no cherry tree, no matter how robust its genes, can grow in the Kalahari, a child raised in crushing poverty by illiterate parents is unlikely to score well on IQ tests, no matter what his mental inheritance. (There are exceptions, of course: the late nineteenth-century Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan was raised in a one-room adobe hut and learned mathematics mostly from two books, both in a foreign language.) Twin studies tend to attract few subjects in such dire straits, so their findings may not always apply to people exposed to extremes of deprivation or privilege. Whenever the Twain Shall Meet / 7 240 245 250 255 260 265 270 275 280 28. All in all, most psychological variability is probably shaped by experience, just as radical environmentalists have always believed. Those experiences, however, are largely self-selected, and that selection is guided by the steady pressure of the genome. As the geneticist Nicholas G. Martin of the Queensland Institute of Medical Research in Brisbane, Australia, and his colleagues argued in 1986: [People are] exploring organisms whose innate abilities and predispositions help them select what is relevant and adaptive from the range of opportunities and stimuli presented by the environment. The effects of mobility and learning, therefore, augment rather than eradicate the effects of the genotype on behavior. 29. That point of view has implications that differ markedly from those of either biological or environmental determinists. Rather than trying to forcibly shape traits and abilities – by constantly pushing an introverted child into play groups, for instance, when she would rather read alone; or by making a child study math when he wants to study art – parents and policy makers should provide supportive environments and a wider range of specialized opportunities (art schools, science schools, theater schools and so forth) at every level of education. 30. The implications of all this for human cloning are quite clear. If clones are simply identical twins by another name, there is no reason to believe they will be any more similar than such twins are. In fact, because clones and their adult forebears would be born into different generations, from different wombs, and have different arrays of environmental choices, there is every reason to think they will be even more different from each other than identical twins are. If a clone and his forebear both inhabit sufficiently rich and varied environments, they will probably make themselves into somewhat similar people. They will, however, be far from identical. 31. Identical twins, I often say, can be compared to two renditions of a piano concerto played by musicians with different styles and skill levels. The written piece of music constitutes a set of specific instructions, yet each version, while clearly identifiable, carries the unique stamp of its performer. Similarly, twins, while created from the same genetic instructions, bear the indelible marks of their development under unique circumstances. 32. Like all analogies, that one is somewhat misleading: the differences between two performances is a systematic product of the musicians’ training, practice and preference for a particular style. Many investigators of twins increasingly realize, by contrast, that a significant amount of the variation between the identical twins in a pair is caused by neither nature nor nurture, but by developmental noise. Whereas nurture implies systematic or controlled environmental influences, developmental noise is chaotic and probably the result of accidental and random environmental effects. Animal breeders have taken great pains to control the environments in which their charges are reared, but developmental noise still influences everything from an animal’s weight to its behavior. Whenever the Twain Shall Meet / 8 285 290 295 300 305 310 315 320 33. Unfortunately, the nuances and gray areas in that picture – the developmental contingencies and fuzzy connections between cause and effect – tend to get lost in any public discussion of cloning. In spite of all the lip service paid to socialization in recent decades, the news about Dolly touched on an abiding fatalism in the general public – a suspicion that genes rule our destinies as implacably as the three Fates once seemed to do. 34. More than 1,500 years ago, the public was entranced by a different kind of determinism – astrology – that Saint Augustine tried to dismiss with arguments strikingly similar to my own. “If the distance of time between the births of twins is so great as to occasion a difference of their constellations … that even from such change there comes a difference of destiny, how is it possible that this should be so, since they cannot have been conceived at different times?” he asked in The City of God. 35. According to Augustine, the mathematician Nigidius answered with a compelling logic of his own. Given the great speed with which the celestial spheres revolve, Nigidius said, even minute differences in the time of birth can create large differences in people. But Augustine countered with what today would be called a psychometric argument. If such small differences have such a large effect on the outcome, he said, then no one measures ordinary birth times with sufficient precision – ipso facto, all astrological predictions must be seriously in error. 36. Today Augustine seems the clear winner of the debate, not least because astrology is widely acknowledged as superstition. But the fact is that Augustine made many biological errors (he did not realize, for instance, that only identical twins, and not fraternal twins, are conceived simultaneously), and he was arguing on behalf of what many might call another superstition: Christian doctrine. In the same way, today’s arguments about cloning are more cultural than scientific. Biologists still do not fully understand the etiology of natural twinning, so tomorrow’s discoveries may undermine today’s theories (a common event in empirical science and one that distinguishes it from ideology and superstition). But that will not stop people from arguing for and against the creation of human clones, or from stressing or deemphasizing the clones’ relative individuality. 37. Consider a few cultural attitudes towards twins. In some societies it was once common to kill one twin; in others both twins were killed; in others only male-female pairs were killed; and in still others twins were welcomed and seen as a blessing. How much each tribe knew about twins probably had little to do with how it decided to treat them. 38. The results of twin studies, I believe, refute both biological and environmental determinism. They do not negate the effect of the environment on behavior, nor do they over-glorify the role of genes. They account for the uniqueness of each of us and remind us that we are an integral part of a complex biological world and not apart from it. whether we will heed that knowledge is another matter. Whenever the Twain Shall Meet / 9 Answer in your own words. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Answer the following question in English. What did the author find most striking – paragraphs 1-2 – about the behaviour of the two people he had met? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the following question in English. What scientific conclusion was the author driven to – paragraph 2 – by his experience with the identical twins? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the following question in English. What thesis appears to be disproved by the experience with the identical twins described in paragraphs 1-3? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the following question in English. What do Galton’s anecdotes – paragraph 6 – suggest? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the following question in English. In paragraph 10 the author keeps coming back to the similarity of identical twins whether reared together or apart; does this fact necessarily suggest that if they were given an intelligence test they would achieve the same results? Elaborate and substantiate your answer. Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Whenever the Twain Shall Meet / 10 Answer the following question in Hebrew. 6. What does the fact that one of the twins – paragraph 11 – is gay and the other is straight tell us about the factors shaping our sexual preferences? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ 7. Answer the following question in English. In what sense could one consider the information provided in paragraphs 11-12 as rather comforting? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the following question in Hebrew. 8. What thesis is reinforced by the fact – paragraph 13 – that though genetically overwhelmingly alike, humans are yet so different from gorillas? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ 9. 10. Answer the following question in English. Compare the author’s view on intelligence heritability with that of Leon J. Kamin – paragraphs 19-20. Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the following question in English. What makes intelligence testing – paragraph 19 – such a delicate issue? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the following question in Hebrew. 11. What makes the claim, that the influence of socioeconomic status upon I.Q. – paragraph 23 – tends to fade entirely by adulthood, not entirely convincing? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Whenever the Twain Shall Meet / 11 12. Answer the following question in English. What could make the statement that unrelated adults who have been reared together (when one is adopted, for instance) ought to have similar IQ scores – paragraph 25 – appear rather disingenuous? Answer: _____________________________________________________________ Answer the following question in Hebrew. 13. A. What does the fact that clones – paragraph 30 – are unlikely to be exact replicas of their forebears suggest? B. How is it relevant to the whole issue of education? Answer: A. B. Choose the best answer. 14. What does the alarm caused by the first act of cloning suggest? Answer : It suggests that we a. all fear that cloning is inevitable. b. suspect too many evil characters are likely to be replicated. c. suspect one’s fate is indeed determined by one’s genetic equipment. Answer the following question in English. 15. In what sense can one say that the article ends on a hopeful note? Answer: _____________________________________________________________