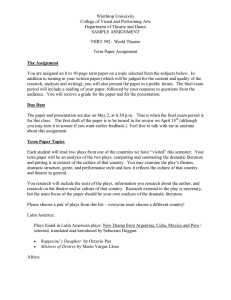

Simon Barker and Hilary Kinds, eds

advertisement

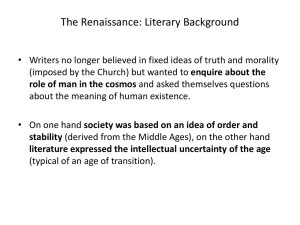

Simon Barker and Hilary Kinds, eds., The Routledge Anthology of Renaissance Drama (London: Routledge, 2003) ix + 457 pp. £16.99 pb. David Bevington with Lars Engle, Katherine Eisaman Maus and Eric Rasmussen, eds. English Renaissance Drama: A Norton Anthology (New York and London: W. W. Norton, 2002) lx + 1997 pp. £24.95 hb. Simon Barker and Hilary Hinds have brought together an edited collection of ten plays and one masque printed and performed in London in the period between the 1580s and 1630s: Thomas Kyd, The Spanish Tragedy, Arden of Faversham (anon.), Christopher Marlowe, Edward II, Thomas Heywood, A Woman Killed with Kindness, Elizabeth Cary, The Tragedy of Mariam, Ben Jonson, The Masque of Blackness, Francis Beaumont, The Knight of the Burning Pestle, Ben Jonson, Epicoene, Thomas Middleton and Thomas Dekker, The Roaring Girl, Thomas Middleton and William Rowley, The Changeling, and John Ford, ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore. The editors spell out the principles behind their selection: the wish to make accessible a number of important non-Shakespearean plays, and the decision to give priority to plays not currently available in affordable editions (though a number, including the first-named are so available). They have excluded widely-republished plays by playwrights such as Marlowe and Jonson, and have chosen to include work by Heywood, Middleton and Beaumont, presumably thinking these playwrights underappreciated; though it would be hard to argue that The Changeling and A Woman Killed or even The Knight of the Burning Pestle are insufficiently studied. The plays are introduced and contextualised both by a general Introduction, and by individual headnotes and discussion. A succinct commentary, drawing on previously-published editions, is provided for each text, and account is taken of textual variants. The result is a usable collection bringing together an ample selection of playtexts. There are caveats to enter, as is perhaps inevitable in a publication as wide in its scope as this one. The edition is, quite properly, addressed to those new to the study of early modern drama, so that some loss of subtlety and nuance is bound to occur. The Chronology throws up debatable assertions, such as attributing the date of Women Beware Women to 1625, basing the dating on ‘the first known performance or, where there is some doubt about this, the date the critics agree is the most likely’, neither of which is true. A petition of 1619, complaining about the nuisance of excessive use of carriages, quoted in the Introduction, is too late to allow the inference drawn from it about the elevated social composition of part of the audience. The influence of early Italian opera on English theatre would, without some qualification, be a surprise not only to its creators but to modern scholars, while the claimed influence of Aristotle in the early modern period on ‘establishing the ideal form and structure of a play’ is to say the least open to question. But it would be wrong to undermine the general scholarship of the editors’ work, which will stimulate new students to think more widely about the plays of the period. Bevington’s anthology with its four contributors is an even more ambitious enterprise, incorporating 27 works of the period, including all those in the Barker anthology, with the exception of A Woman Killed and The Masque of Blackness, but adding in John Lyly, Endymion, Robert Greene, Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay, three further plays by Marlowe, Thomas Dekker, The Shoemaker’s Holiday, John Marston, The Malcontent, three further, major, plays by Jonson, Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, The Maid’s Tragedy, Fletcher’s The Woman’s Prize, two single-authored plays by Thomas Middleton and one (The Revenger’s Tragedy) of doubtful ascription, John Webster, The White Devil and The Duchess of Malfi and Philip Massinger, A New Way to Pay Old Debts. This mixture combines plays long considered part of the mainstream of Renaissance drama with lesser-known works by Cary and Fletcher, though the first of these has received a great deal of critical attention of recent years and is included in the Barker anthology. While the plays have been edited afresh from the most authoritative early texts, the collection has been adapted to the needs of the undergraduate reader by glossing even relatively familiar words and phrases, and by offering explanatory footnotes the advanced reader will not need. Spelling and punctuation have been modernised, though the editors have adopted a conservative stance towards the original texts, preferring to keep an early reading ‘where it makes sense’. Editors of early modern plays will recognise the set of dilemmas Bevington and his collaborators have faced and necessarily resolved. On the whole, there will be general agreement that a highly responsible and scholarly edition has been brought together, though sticklers for older language forms, and some theatre scholars, may regret the decision ‘to use modern conventions of punctuation to clarify for today’s readers the language that early modern writers would have punctuated somewhat differently’. Some theatre-wise readers may feel that such a policy corsets the freedom of stage speech. The collection’s General Introduction, by Katherine Eisamen Maus and David Bevington, surveys with a light but authoritative touch the scholarship of Renaissance theatre, beginning, encouragingly, with the auditoria and playing companies. Readers may quibble about details, for instance that the exterior measurement of the Globe was ‘probably’ about 100 feet across, a view contested in recent scholarship as being too large, or that there was a decrease in extra-London touring during the later sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, a statement which must now be read in the light of Siobhan Keenan’s Travelling Players in Shakespeare’s England. But not only is the scholarship widely knowledgeable and up-to-date, many will welcome its independence in recuperating non-Shakespearean drama in comparison with Shakespearean. The editors place actors and acting in a social, political and educational context that illuminates theatre business and provides insight into the culture which nurtured the period’s explosion of talent. They discuss theatre language and the influence of older theatre forms, both native and classical, dress codes and assumptions about social class, the development of commercial enterprise and consumption, sex, marriage and gender, and the powerful but uncertain impact of religion on the plays’ language and structures of belief. Finally, they consider the relationship between playing, print and theatre attendance. Altogether, this represents a comprehensive account of the state of English theatre in the relevant period, wonderfully inclusive, individual without being opinionated, and manifestly the work of scholars of the highest calibre. Altogether this is a vastly useful anthology which may be given to beginning readers of Renaissance drama with confidence. Ronnie Mulryne University of Warwick