Lea Countryman (with Brian Morgan)

advertisement

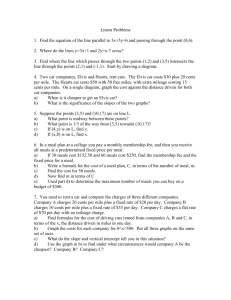

Nibbling versus gorging: More Meals May Mean More Health. A Guidelines Paper for General Public Lea Countryman & Brian Morgan Spring 2005 A paper for Health Magazine In an era of bigger is better, and fast seals the deal, the notion of smaller meals spread out throughout the day may seem difficult and time consuming. But when it comes to health, smaller meals throughout the day may very well turn out to be a prescription for a healthier life. Americans eat on average, 3.12 meals a day. Is this enough? How does the frequency of one’s eating affect general health? And does it have an effect on body weight, heart disease or even cancer? Much today is being written about diet and nutrition, most of which focuses on what to eat, but little attention is being given on how to eat. Indeed, whether it is “better” to eat many small meals a day or have fewer large meals is a common question. Comparing the potential benefits of nibbling and of gorging has been the focus of much animal and human research, but no clear consensus has emerged. Varied conclusions from research show that this issue is unresolved and requires more attention (see Tables 1,2,3). Some research has found a connection between nibbling as a meal pattern and decrease in weight (11). Other studies have shown that fewer meals taken throughout the day leads to weight gain (3). Risk for Cardiovascular disease may be decreased by increasing meal frequency because of the reduction of harmful cholesterol in the blood (12,16). But another group of researchers found that increasing meal frequency does not decrease harmful cholesterol and therefore does not reduce the risk of heart disease. 1 When it comes to colon cancer, increasing meal frequency can be very harmful. In fact research has found increasing meal frequency can increase the risk of colon cancer by 50% in men (18). The research is scattered; some studies found benefits and some found no benefits from increasing meal frequency. Although many studies showed no benefits there seems to be greater support in favor of meal frequency for overall improvement of health. The following examines the research on meal frequency for each individual health category: obesity, cholesterol, heart disease and colon cancer. Will Eating More Often Make You Thinner and Healthier? Most of us know our country is in trouble when it comes to our weight. Nearly two-thirds of adults in the United States are overweight and more than 30 percent are obese (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases 2003). What may come as a surprise, is the alarming rate at which people are losing their battle with obesity. According to a recent report, the number of individuals considered morbidly (people with a BMI of 40 or higher) or severely obese (people being 100 lbs over Body Mass Index (BMI) is a scientific way of relating weight in lbs to height in inches. BMI is commonly used as a measure of persons obesity. However it does not differentiate between body fat and muscle. So a person with a high BMI may not be obese. weight) rose from 1 in 200 adults in 1986 to 1 in 50 in the year 2000 (4). To make matters even worse, the number of people with a BMI of 50 or greater escalated from 1 in 2,000 to 1 in 400 during this same time period (4). Statistics like this are frightening when you consider the health consequences of being overweight or obese. We now know a laundry list of risk factors associated with obesity such as type II diabetes, heart 2 disease, high blood pressure and limited mobility, which can seriously threaten how long and how well people live. Nibbling throughout the day is showing to be a good way to regulate weight and loose unnecessary fat. According to a recent report, people who eat more frequently will be thinner (11). This study of 499 people monitored the effects of overall caloric intake and exercise. They found that, on average, participants ate just under four meals each day (3.92). Men ate an average of 2,259 calories daily, and women ate 1,641 calories daily. People who reported eating four or more times per day were 45 percent less likely to be obese than those who reported eating three or fewer times each day. In addition, people who skipped breakfast were 4.5 times more likely to be obese than people who regularly ate breakfast. This could be because the study found that on days participants skipped breakfast they ate more. Perhaps we are like ravenous wolves that if deprived of food for a long time, and are then presented with food, eat as if they may never see food again. This could be because of the body’s natural survival instinct; if food is scarce, you’d better stuff yourself as best you can, because you don’t know how long it will be before you will find food again. In addition, the International Journal of Obesity & Related Metabolic Disorders reported that frequent meals reduced appetite by 27%! This could be very beneficial for people trying to lose weight and eat a more healthy diet. The study was conducted using two groups of healthy overweight men. One group had a large breakfast, then the second meal five hours later, with no snacking in between. The second group ate the same amount of same food but divided it into five meals, given hourly. After both groups had completed the five hours they were given an “all you can eat” meal, and which group ate 3 more? Yes, the gorgers. These studies suggest that increased meal frequency can reduce the risks of obesity appear to be very promising. However there is other research that does not agree with these findings. A review, conducted by Bellisle F, et al. (1997), examined many studies, which observed the relationship between meal frequency and obesity (2). This review argued that many of these studies found that there was little or no effect of meal frequency on obesity. Also the studies much like the ones mentioned above, which did find that increased meal frequency lessened the risk of obesity, were criticized by this review for showing weak evidence of this relationship. In addition, subjects may have been under reporting what they ate leading to insufficient data. The review concluded that there is insufficient evidence that weight loss can be attributed to the number of meals a person eats per day. However, some of the experimental failings of the studies reviewed by Bellisle F, et al. were addressed with greater rigor by the subsequent Ma Y, et al study (2,11). In addition most studies on obesity and meal frequency attempt to isolate the element of meal frequency, yet stress, physical activity, and pre-existing eating tendencies have a large effect on the participants. More research with a more realistic approach and greater populations is needed to see if meal frequency is in fact the main element that effects weight loss, or if other elements also contribute. Regardless it appears for now that increasing meal frequency is beneficial for weight loss. 4 Obesity Research (Table 1) Research which found that eating more meals has Positive effects on Obesity Ma Y, et al 2003 Found: The more meals that the subjects ate per day (greater than 3) decreases the risk of obesity Bray GA 1972 Found: The more meals that the subjects ate per day decreased obesity and the fewer meals the subjects ate per day increased the risk of obesity Research that displays meal frequency has Negative or No Effect on Obesity Bellisle F, et al. 1997 Found: There is no evidence that weight loss is affected by the number of meals you eat per day. This chart compares different research on the effects of the number of times per day you eat with the risks of obesity. Will Eating More Often Lower Risk for Cardiovascular Disease? Our blood carries cholesterol in the form of low-density lipoproteins and highdensity lipoproteins. LDL’s (low density lipoproteins) are a form of cholesterol which if found in large quantities are harmful to the body. They are a leading contributor to cardiovascular disease because of their sticky nature. Where as HDL’s (high density lipoproteins) are a form of cholesterol that are not considered harmful in the same way LDL- low-density lipoproteins transport cholesterol in the blood, but LDL’s are more fat than protein and stick to each other and your tissues, which is very dangerous. LDL’s are. Many Americans are facing problems with high amounts of LDL’s and coronary heart disease as a result. Studies are showing that increased meal frequency can reduce LDL HDL- high-density concentrations in the blood as long as total caloric intake is not lipoproteins transport cholesterol in the increased (7). In fact nibbling can decrease total cholesterol HDL blood. They are equal parts lipid and protein and LDL, but raise the HDL/LDL cholesterol ratio (12). When 19 and it does not stick to each other and your females were either given three meals per day or nine meals per day tissues. for two weeks, there was a significant decrease in LDL levels 6.5% (1). 5 However Murphy MC et al. 1996, found no change in cholesterol amounts for healthy young women with increased meal frequency (13). In addition they found that HDL amounts were increased on the gorging diet (3 meals/day) versus the nibbling diet (12 meals/ day). One strength of this study was that there was intense control over the diet that people ate. The studies that found benefits in LDL cholesterol levels from increasing the number of meals they ate per day did not have such rigorous restrictions and control over their subject’s diets. It is important to note that this study was conducted over a two-week period with females age 22-23. This is a limiting factor because it only looked at very young females and it also could have been conducted over a longer period of time to show that these results stay constant. Figure 1 Reductions in LDL and Total Cholesterol Levels With Increasing Meal Frequency 0 Percent Change in -5 Cholesterol -10 Level -15 LDL Cholesterol Total Cholesterol Jenkins et al. Arnold et al. Study This graph is a comparison of two of the studies that found more meals per day could mean lower cholesterol levels for harmful LDL cholesterol and total cholesterol. Both of the studies found that there were significant reductions in percentages of LDL and total cholesterol in their subject’s blood when they ate more meals per day as seen from this graph. Heart disease is the leading cause of death in America today and rising; meal frequency may help remedy that problem. Fabry (1964) and his group from Czechoslovakia examined 279 men, ages 60-64, for the consequences of nibbling diets 6 under normal living and working conditions (8). It was found that obesity, cholesterol and heart disease increased as the frequency of meals decreases. In a Ischemic Heart Disease (IHD)- is a form of heart disease caused by a blockage of blood to the heart. later study conducted in 1968, the Czech group surveyed 1133 men ages 60-64 and found that ischemic heart disease (IHD), IHD was decreased for subjects who nibbled versus gorged. They found a distinct relationship with meal frequency from 30% in the group who ate 3 meals or less, with those who ate 5 meals or more who only had 20% with IHD (9). In another study seven healthy men consumed identical diets as three meals per day or as 17 meals per day. Studies found that risk for cardiovascular disease was reduced by 9.9% (see Figure 1) (10). However, this study is limited by its small population and that it only compared 3 meals /day to 17 meals per day. Although they are extremes, it is not realistic for a person to eat 17 times in a day. More research is needed that could be practically applied to the general public, as in 5-7 meals per day. But it seems that heart disease and cholesterol are very closely associated and that decreased cholesterol leads to a decrease in risks for heart disease. Therefore spreading the times you eat food, throughout the day may help reduce risks for heart disease. Cholesterol and Cardiovascular Disease Research (Table 2) Research which found that increased meal frequency had Positive effects on cholesterol levels and CVD Titan MO, et al. 2001 Found: More meals per day decreases the concentrations of total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol in men and McGrath SA & Gibney MJ 1994 Found: More meals per day has a positive effect on raising HDL cholesterol levels and 7 Edelstein SL, et al. 1984-87 Found: More meals per day might result in reduced levels of cholesterol women More Positive Research decreasing LDL cholesterol levels Arnold LM, et al. 1993 Found: 9 meals per day compared to 3 meals per day reduced LDL and HDL cholesterol levels by 8.1% and 4.1% Jenkins DJ, et al. 1995 Found: A nibbling diet lowered both LDL and HDL levels when compared to a control diet Fabry P, et al. 1968 Found: More meals per day lowers the risk of Ischameic (blockage related) heart disease Research that displayed increased meal frequency had Negative or No Effect on cholesterol levels and CVD Murphy MC, et al. 1996 Found: There was no change on LDL cholesterol concentrations with a nibbling diet. Also a gorging diet increased the HDL cholesterol levels. This chart compares differences in research for cholesterol levels and cardiovascular disease. For the most part the research suggests that that increasing meal frequency can reduce LDL cholesterol levels which can be harmful and cause blockages in arteries, especially arteries involved in heart function. However, there is some research which did not find eating more meals per day to be beneficial in decreasing LDL levels. Can I Get Colon Cancer From Eating More Often? Colorectal or otherwise known as colon cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States (15). And although nibbling may improve such health factors as obesity and heart disease studies show that increased meal frequency may lead to an increased risk of colon cancer (6,18). Researchers have found that by increasing meal frequency the colon is exposed to more bile acid and therefore has a higher risk of cancer (18). In addition, decreasing meal frequency down to one to two times per day decreased the risk of colon cancer by 50%. However, for women increasing meal frequency had no effect on colon cancer (see Figure 2) (6,18). Figure 2 8 Comparison of the Risks of Colon Caner for Men and Women 80 Percent 60 Risk of 40 Colon Cancer 20 Males Females 0 1,2 3,>3 Number of Meals Per Day This graph is a general representation of the findings of the two studies which examined the effects of meal frequency and colon caner risk. As you can see from the graph the males who ate 3 or more times per day had a 50% increase in the risk of getting colon caner. Also the female subjects had no significant differences in the risk of colon cancer between different meal frequencies. *This graph is just a representation to show the general trend of the findings of these studies and does not show the actual data from the studies. The research found that there was no positive effect of increasing meal frequency on colon cancer; all effects were negative. In addition this research is limited only to colon cancer. No research has been found which suggests that increasing meal frequency would increase the risk for other types of cancer. Therefore men with a family history of colon cancer should be wary of an increased meal frequency, eating pattern. But there seems to be no negative for women to nibble away when it comes to risk of colon cancer. Colon Cancer Research (Table 4) Research which found that increased meal frequency had Negative effects on the risk of Colon Cancer Coates AO, et al. 2002 Found: Men who ate fewer meals per day (1-2) had a decreased risk of colon cancer by 50% compared to those who ate 3 or 9 Wei JT, et al. 2004 Found: Men who ate fewer meals per day (1-2) had a decreased risk of colon cancer by 50% compared to those who ate 3 or more times per day. Meal more times per day. Meal frequency did not appear to have frequency did not appear to have an effect on colon cancer risk in an effect on colon cancer risk in women. women. Both of these studies found that an increase in the number of meals men eat per day can have a negative effect on their risk for colon cancer. Although this is very important for men, the research did not show the same pattern for women and suggested that meal frequency does not have an effect on colon cancer risk. Nibbling versus Gorging So is it better to eat three square meals per day or more as in five or six? There is some research that shows that increasing meal frequency has no effect on health factors such as obesity and cholesterol, and can in fact increase the risk of colon cancer in men. However, as shown above there seems to be a greater body of evidence in support for increasing meal frequency due to the positive health benefits such as decrease in obesity and a decrease in cholesterol. Most of these studies point clearly to the need for additional research. A larger number of participants and the inclusion of variables strongly influenced by human behavior, physical activity, diet, and stress might provide a better understanding of eating frequency on overall health. At the current time, it seems that eating more than the average 3.12 meals per day is beneficial for one’s health! It comes down to risk versus benefit, and when it comes to nibbling versus gorging, nibbling appears to be a better strategy. The Real Deal Although the research on meal frequency in encouraging, nutrition experts caution that increasing meal frequency without increasing total energy intake can be a daunting task for most. According to Sarah Garner, RD, a weight loss expert in Denver, 10 the general population is exposed to conflicting messages about dieting. She fears that consumers may get more confused than ever if they attempt to increase how many times a day they eat while changing what they are eating. Garner says that, even when clients are committed to improving their health, it is difficult to alter a lifelong habit of loading up on empty calories from sodas and junk food at three major meals. So is increasing meal frequency a realistic goal for those trying to improve health? Some experts doubt, but they add the caveat that altering one’s diet in the right direction may still be helpful. According to Walford, increasing meal frequency by even a moderate amount (1-2 more meals /day) can provide some of the benefits of a more nibbling approach (16). In light of such findings, creating a more frequent meal plan, in addition to watching what one is eating, and obtaining adequate physical activity may be a realistic goal. Although beneficial at any age, moving toward a lighter more frequent diet and leaner body can be important, especially as people grow older. Studies have found that being over weight in middle age (35-45) can cut as much as 3 years off a human’s life expectancy (Caruso 2003). Overall nibbling your way through life seems to be a good way to decrease the risk of many health problems but more research must be done on meal frequency in relation to cancer. Perhaps you can implement a nibbling pattern to your life and find a healthier you. 11 References: 1. Arnold LM, Ball MJ, Duncan AW, Mann J. Effect of isoenergetic intake of three or nine meals on plasma lipoproteins and glucose metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993 Mar;57(3):446-51 2. Bellisel F, McDevitt R, Prentice AM. Meal frequency and energy balance. Br J Nutr. 1997 Apr; 77 Suppl 1: S57-70. 3. Bray GA. Lipogenesis in Human Adiopose Tissue: Some Effects of Nibbling and Gorging. J Clin Invest. 1972 March;51(3):537-548. 4. Brink, s. 2003. America’s Expanding Waistline. USNews.com,www.usnews.com/usnews/issue/031027/health/27fat.b.htm. 5. Caruso, D.B. 2003. Obesity in Middle Age Cuts Years Off Life. Associated Press. January 6. 6. Coates AO, Potter JD, Caan BJ, Edwards SL, Slattery ML. Eating frequency and the risk of colon cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2002;43(2):121-6 7. Edelstein SL, Barrett- Connor EL, Wingard DL, Cohn BA. Increased meal frequency associated with decreased cholesterol concentrations; Rancho Bernardo, CA, 1984-1987. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992 Mar;55(3):664-9 8. Fabry P, Fodor 3, Heji Z, Braun T, Zvolankova K: The Frequency of Meals: Its Relation to Overweight, Hypercholestrolemia, and Decreased GlucoseTolerance. Lancet 2:# 7360, 614-615, 19 September 1964. 9. Fabry P, Fodor 3, Heji Z, Geizerova H, Balcarova O and Zvolankova K: Meal Frequency and Isehaemic Heart- Disease. Lancet 2: #7561, 190-191, 27 July 1968. 10. Jenkins DJ, Khan A, Jenkins AL, Illingworth R, Pappu AS, Wolever TM, Vuksan V, Buckley G, Rao AV, Cunnane SC, et al. Effect of nibbling versus gorging on cardiovascular risk factors: serum uric acid and blood lipids. Metabolism. 1995 Apr;44(4):549-55. 11. Ma Y, Bertone ER, Stanek EJ 3rd, Reed GW, Hebert JR, Cohen NL, Merriam PA, Ockene IS. Association between eating patterns and obesity in free-living US adult population. Am J Epidemiol 2003 Jul 1; 158(1):85-92 12 12. McGrath SA, Gibney MJ. The effects of altered frequency of eating on plasma lipids in free- living healthy males on normal self-selected diets. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1994 Jun;48(6):402-7 13. Murphy Mc, Chapman C, Lovegrove JA, Isherwood SG, Morgan LM, Wright JW, Williams CM. Meal frequency; does it determine postprandial lipaemia? Eur J Clin Nutr. 1996 Aug;50(8):491-7 14. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 2003. Statistics related to overweight and obesity. Weight-Control Information Network, www.niddk.nih.gov/health/nutrit/pubs/statobes.htm;retrieved October 21, 2003. 15. The American Gastroenterological Association. 2005. AGA Urges Expansion of Coverage for Colorectal Cancer Screening to Enhance Early Detection. Clinical Issue Brief: http://www.gastro.org/pubPolicy/issueBriefs/urges.html. 16. Titan SM, Bingham S, Welch A, Luben R, Oakes S, Day N, Khaw KT. Frequency of eating and concentrations of serum cholesterol in the Norfolk population of the European prospective investigation into cancer: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2001 December:323(7324): 1286 17. Walford, R.L.,et al. 2002. Calorie restriction in Biosphere 2: Alterations in physiologic, hematologic, hormonal, and biochemical parameters in humans restricted for a 2 year period. Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and medical Sciences, 57 (6), B211-24. 18. Wei Jt, Connelly AE, Satia JA, Martin CF, Sandler RS. Eating Frequency and colon cancer risk. Nutr Cancer. 2004;50(1):16-22. 13