Evensong 6 Easter B 2012 St Paul`s Cathedral 6

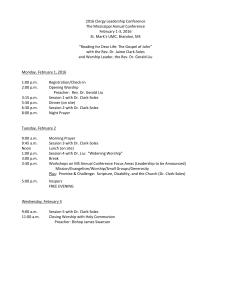

advertisement

Evensong 6 Easter B 2012 St Paul’s Cathedral 6.00pm Many of you will know that before St Paul’s Cathedral was built there was, on this site, a substantial stone church also called St Paul’s which had been built in the early days of the settlement of Melbourne. In those early days an American merchant named George Train settled briefly in Melbourne and took an active part in its life. George Train was a Methodist but he attended the newly opened St Paul’s Church on one occasion in 1853 - I suspect only one because he wrote afterwards that he had never in his life attended so wearisome a service, over two hours in length, and that he found the constant repetition of prayer for Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and the Royal Family especially off putting. Poor George! Apart from the fact that the frequent references to British royalty must have grated on his Republican consciousness I think there would have been two factors that made the worship more tedious than it should have been, not just for him but everyone. First– length and repetition; in those days it was the custom in the Anglican Church for the separate services we know as Morning Prayer or Mattins, the Litany and the Communion Service to be joined into one long act of worship which was very wordy and involved much repetition, with prayers for the Queen and royal family occurring twice in each of them. Second; the long and wordy service would have been almost entirely said. There would have been very little music to relieve the stream of spoken words. The Bishop of Melbourne at that time was very strongly opposed to the singing of services and did his best to forbid it happening in Melbourne’s early churches. The Bishop, Charles Perry, who was Melbourne’s first bishop, was certainly a devoted, hard working and far seeing servant of God. Confronted with the enormous task of laying a foundation for the Church in a colony whose population was exploding as a result of the Gold Rush, Bishop Perry travelled tirelessly founding new parishes across Victoria and persuading clergy to come from England to fill them - which was no easy task. Confronted with intellectual challenges to the faith raised by advances in biological, geological and historical sciences he responded in as capable a manner as was possible for him at the time. He was intelligent and a good scholar – first class honours graduate in Mathematices from Cambridge University. Confronted with the need to set up an organizational structure for the Church he chose the democratic model of a synod comprising two elected lay representatives for each clergyman - a first in the British Empire what has become the Anglican pattern of diocesan organization everywhere. But confronted with a robed choir singing the Magnificat or a priest singing the Collects he would go bananas, reacting in a negative, emotional and authoritarian way that was quite out of keeping with his usual rational approach to things. Music, he claimed, distracted people from the meaning of the words so that the service was reduced to the level of a secular concert. So insistent was he in laying down his strictures on what could and could not be done musically in church that the St Paul’s Church choirmaster George Allen (founder of the well known Allen’s Music stores - still in existence) on one occasion resigned in protest along with the whole of the choir. Even after Perry had retired and returned to England, to be replaced by the much more tolerant Bishop James Moorhouse, his influence continued through some clergy. Just before St Paul’s Church was due to be demolished to make way for the Cathedral the choir and organist once again resigned en masse. By then, however, a decision had been made that a special choir would be formed for the new Cathedral. Members for the future St Paul’s Cathedral Choir had been auditioned and were practising for three years before the Cathedral was completed so that they could sing at its opening - which they did on January 22nd 1891. So to those boys who were admitted to membership, or an office of special responsibility, in the choir tonight, remember that You have become part of a choir which sang at the first service held in the Cathedral and has continued an unbroken history of singing over the 121 years since. You have become a part of that long history and have taken upon yourselves the task of keeping up its standards in our time. But of course the use of music in worship goes back much further than the 121 year history of St Paul’s Choir and the revival of choral church music in the mid nineteenth century in which St Paul’s choir was a participant, not just a passive product. It goes back through the hymns of the eighteenth century Methodists - John and Charles Wesley - and Evangelicals like John Newton and others, to the great Lutheran hymns and chorales of the Reformation to renaissance polyphony; and then through centuries of mediaeval monks chanting plainsong, back to the lesser known chants of the Byzantine period, some of which were performed in a concert here last night by the Melbourne Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir. We know that Jesus and the disciples sang together as part of their worship of God. The Gospel of St Mark tells us that after Jesus had taken the bread and wine at the Last Supper, declared them his body and blood and commanded the disciples to continue this act, they sang a hymn before going out to the Mount of Olives. St Paul, in his letters to Christian communities, speaks of them singing hymns, psalms and spiritual songs in their gatherings for worship. In the period just after the New Testament around the year 120 CE Pliny the Younger, Roman Governor of Pontus, the region near the Black Sea, wrote a report to the Emperor Trajan on the sect of the Christians in his region. He had found by examination, he wrote, that the members of this sect met early in the morning on an appointed day to sing a hymn antiphonally to Christ as to a God and to meet later in the day to take food together. (Antiphonally means each side singing in turn as if answering the other, a kind of singing or saying of the psalms or other pieces still practiced in worship today). Pliny also reported that the ‘contagion of this superstition’ had spread not only in the cities but in the towns and rural regions as well Christianity grew in large measure because it had a faith based on a flesh and blood saviour rather than a figure of mythology; because it taught, and its members practised, an unselfish moral code; and because its worship engendered a strong sense of solidarity among its members. Communal meals and a musical tradition, both inherited from the parent Jewish body, and referred to in Pliny’s letter contributed to this solidarity. As years and centuries passed, and the Gospel message spread ever more widely among the nations, flexibility and the ability to draw upon various cultural traditions played an important part also. In particular, at all stages of the development of the musical tradition of the Church, from its Old Testament Jewish roots right down to the present, the Church has drawn upon the musical traditions of the cultures in which it has found itself - this often to an extent unrealized. People have debated whether or not there is something uniquely different about the music of worship that distinguishes it absolutely from secular music; whether, in other words, there is a special kind of music which alone is capable of supporting worship. The answer seems to be No that the context, the way it is sung and appropriate words can enable any music that is capable of moving the human heart to assist religious devotion also - whether reflection, penitence, praise or commitment. The same music in another context, might stir the heart to feelings of romantic love or patriotism. A familiar example would be the hymn “Glorious things of thee are spoken, Zion City of our God” a hymn which, with the same tune and different words, was the national anthem of the Austrian empire and later of Germany. So, something else for the choir boys to keep in mind. The music you sing has much in common with the classical music tradition in general and so the training you receive in church music, will serve you as a good general education in music. It is noticeable how many celebrity vocalists say that they began by singing in a church choir. A good church choir in a setting like St Paul’s is an asset to any city - witness the tourists and people seeking a time of reflection and inspiration, who come into the Cathedral on weekday evenings when the choir sings Evensong, the daily evening prayer of the Church offered to God in Anglican churches and cathedrals around the world. It is a pity that the number falls away a bit in winter as I think the service acquires a subtle beauty and a deeper meaning in these darker times of the year than in the bright extended daylight of summer evenings. It is a good thing that music can draw people into the church who otherwise would not attend, but that cannot be the conscious purpose of the music. If it is, it will be self defeating. It is the atmosphere of worship, of reflection and inspiration to which the music contributes, and not just the music alone, that can make the atheist declare him or herself publicly a fan of Choral Evensong - something which happened last year in Melbourne. Choir members, you make a necessary contribution to that atmosphere which distinguishes our worship from the same music sung elsewhere. That is why we always stand quietly in the corridor and pray briefly before we move process into church. And we proceed in peace (as we say in our prayer) peace of mind, peace of body and peace with each other in order that our singing may be worship and not simply performance. The distinction comes out clearly at Christmas. In the weeks leading up to Christmas each year most of us get sick and tired of hearing Christmas carols every which way we turn our ears but, despite all that saturation overlay, the crowds still turn up here (and in other churches) in great numbers on Christmas Eve to hear the authentic thing - the carols sung in worship. I know people who experienced, for the first time, in a Christmas Carol Service here, a spiritual awakening which led to further enquiries, to instruction and to baptism at Easter. Worship, with its music, its words and its ceremonial, is an end in itself - an act directed to God - an act involving reflection, learning, penitence and abasement, exhilaration, praise, thanksgiving and offering, offering of self and, in a Christian context, the supreme privilege of bringing to the divine remembrance the sacrifice of Christ for the sins of the world, a sacrifice which brings all other acts of worship into itself and gives them a value that no human offering could ever match, with or without music. And church music is ecumenical. We use music from just about all Christian traditions - Eucharistic settings by Roman Catholic as well as Anglican musicians, hymns from just about every tradition you could name; and conversely Anglican music is used widely in other churches. A bit of Vatican gossip I picked up only today from an English newspaper is that Pope Benedict XVI , who is very musical, was very impressed with the ceremony and music in Westminster Abbey on his recent visit to England and has been acquiring CDs of English choral music. Of course prayer and the offering of the Eucharist or Evening or Morning Prayer are all fully authentic without music. Most worship and most prayer is in fact offered without the benefit of music, but it was well said by St Augustine in the fourth century “Who sings, prays twice.” Qui cantat bis orat. And if those who sing pray twice then those whom their singing inspires, although silent, assuredly pray better. What a privilege then to be in a church choir - to offer one’s voice as well as one’s mind and body to God, in an earthly anticipation of what will be the joy of heaven itself, and to lead and inspire others in the joy of worship through music “the greatest good that mortals know, and all of heaven we have below.” Let us thank God for the gift of music and for the music we enjoy in our worship, praying that it may indeed tune our souls to the melodies of heaven. Amen.