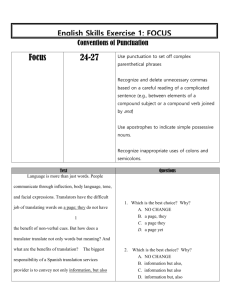

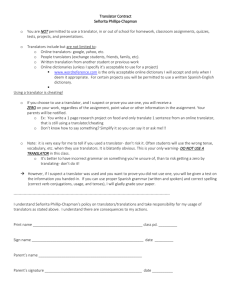

Translation as a Profession

advertisement