The Changing Context of UK State - Voluntary Sector

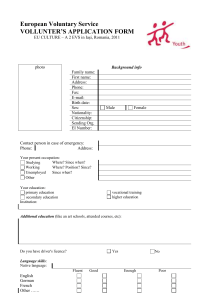

advertisement

A Race to the Bottom? – Exploring Variations in Employment Conditions in the Voluntary Sector INTRODUCTION This paper explores how variations in state – voluntary sector inter-organizational relations influence the employment relationship in the latter, and the capacity of thirdsector organizations to exercise autonomy over employment matters in this relationship. The focus is drawn from an observation that this relationship has grown in recent years as most Western industrialized economies have partly contracted out social services to voluntary organizations (Kendall, 2003). Yet, despite this growth, in contrast to other inter-organizational relations such as public private partnerships, we have limited knowledge regarding its employment outcomes. The UK voluntary sector, normally defined under the ‘Narrow’ definition of the sector (See Kendall and Knapp, 1996), specifically the area of social care, is of particular interest in this regard given the recent dramatic shift in its resource dependence on the state, which is greater than other industrialized countries (Kendall, 2003: McClimont and Grove, 2004: Wilding, Collins, Jochum, and Wainright, 2004). Moreover, in employment terms, the workforce has increased to over six hundred thousand employees who are responsible for caring for some of the most vulnerable in society. In 2004, for example, those employed in social work accounted for over half of the UK voluntary sector workforce (51.6 per cent or 313,000 employees) (Wainwright, Clark, Griffith, Jochum, and Wilding, 2006). Further, the few studies that have explored the implications of this change on employment conditions suggest 1 that management in voluntary organizations largely succumb to external cost pressures from the state, leading to ‘a race to the bottom’ on pay (Cunningham, 2001: Barnard, Broach and Wakefield, 2004). This is of concern given that continued pressure on terms and conditions can only have a detrimental effect on employee morale in the sector and lead to recruitment and turnover problems (Wilding, Collis, Lacey and McCullough, 2003:Alatrista and Arrowsmith, 2004: Scottish Centre for Employment Research, 2005), leading to concerns over the quality of care. However, questions also arise over whether such outcomes are inevitable as an image of complete passivity by the voluntary sector in its relations with the state contradicts work exploring the employment outcomes from other forms of inter-organizational relationships. Here, studies in the private sector reveal the exploitative and detrimental nature of supply chain relationships over the labour process, with subsequent work intensification (Turnbull, Delbridge, Oliver and Wilkinson, 1993:Roper, Prabhu, Zwanenberg, 1997), but also highlight how inter-firm relations are not homogenous and include ‘partnerships’, or the exercise of autonomy and/or the attainment of an advantageous position by suppliers so protecting employment conditions (Hunter, Beaumont and Sinclair, 1996: Truss, 2004: Marchington, Grimshaw, Rubery and Willmott, 2005). This raises questions regarding whether the voluntary sector’s relationship with the state is so dependent as to mitigate against the possibility of autonomy. Or, alternatively, have the aforementioned studies of the sector largely omitted in-depth analysis of the incidence of and conditions determining the exercise of autonomy by voluntary sector employers. 2 In the light of these observations, this paper reports findings from a qualitative study of inter-organizational relations between twenty-four Scottish-based voluntary organizations, and seven local authorities. It begins with an overview of what we know about employment conditions in the sector in the era of contracting, followed by an outline of recent literature on inter-organizational relations and their impact on employment. The purpose of this last section is to provide a framework in which to evaluate prospects for the exercise of autonomy by voluntary sector employers in their relations with the state. This is followed by an outline of the methodology, a report of findings and a concluding discussion. The Changing Context of UK State - Voluntary Sector Relations Studies exploring the impact of the high level of income dependency of voluntary organizations on state funding sources present a mixed picture regarding the outcomes of this relationship. Commentators argue how as with other forms of interorganizational relations, the rhetoric of partnership is utilized when describing relations between government contractors and voluntary organizations (Newman, 2001). However, others raise concerns over the consequences for continued voluntary sector autonomy in the face of coercive influences from the state; greater regulation of the sector; and financial uncertainty (Russell, Scott and Wilding, 1996: Perri 6 & Kendal, 1997: Tonkiss and Passey, 1999: Harris, 2001). Mixed opinion also emerges in the area of employment, where from the 1980s continuous pressure on employment costs in voluntary organisations has led to a drift away from reliance on public sector pay scales to determine rewards (Cunningham, 3 2001: Knapp, Hardy and Forder, 2001: Barnard et al, 2004: Shah, 2004). At the same time, the aforementioned insights do not suggest complete subordination by voluntary organizations in contractual relations. For example, one of the above studies reveals a move away from public sector pay comparability for some organizations in the sector, but not for others (Cunningham, 2001), while another reveals that only twenty per cent of voluntary organizations still use public sector pay scales (Remuneration Economics, 2002). In social care, studies indicate how the majority of voluntary organizations undertaking social services work contracted out by local authorities initially paid their staff according to National Joint Committee (NJC) scales: i.e. pay rates that are comparable to local authority sector workers. However, this approach to rewarding staff declined because of cost pressures leading to organizations increasingly setting pay to reflect local labour market conditions: suggesting a mixture of reward strategies involving public sector comparability and market rates in the sub-sector (Jas, Wilding, Wainwright, Passey and Hems, 2002). However, scrutiny of pay does not give us a complete picture of the impact of costs pressures on working conditions in the sector. A more complete understanding of management strategies to reduce employment costs in a labour intensive area of activity such as the provision of social services also comes from scrutiny of the labour process. This is because the labour process offers an immediate and accessible means to innovate and reduce employment costs (Warhurst, 1997). This can be achieved through intensifying work or diluting skills. The former can manifest through, for example, attempts by local authorities to pressure providers into lowering staff – service user ratios. Skills dilution can occur through funders encouraging the steady 4 routinization of tasks provided to service users, such as funding the provision of domestic chores to the detriment of more social – emotional support to the client. There remain then significant gaps in our knowledge. Specifically, we do not know whether the retention of public sector pay comparability or the protection of other working conditions is a consequence of ‘partnership’ relations, or resistance from providers to pressure from purchasers. Further, we do not have understanding of the factors that determine these outcomes, nor whether they are sustainable or merely delaying the inevitable and that all voluntary organizations will join the ‘race to the bottom’ on pay and conditions. In addressing these gaps in our knowledge, the multi-disciplinary literature on interorganizational relations is useful given its capacity to reveal the range of forces that shape the diversity of relations within inter-organizational networks, and their subsequent impact on the employment relationship. The next section, therefore, highlights some of the key aspects of this literature to provide a framework upon which the paper seeks to explore the capacity of voluntary organizations to exercise aspects of autonomy within the context of its close relationship with state agencies. Factors influencing degrees of subordination and dependency in interorganizational relationships An overview of the literature on inter-organizational relations begins with early studies that highlight subordination between one party and another to sophisticated multi-level analysis that have focused on institutional, organizational and inter- 5 personal influences that explain the complexity and variability of outcomes in such relations. To begin, Rainnie in exploring contracting in supply chains uncovered different levels of vulnerability and dependency between buyers and suppliers (Rainnie, 1989 and 1992) leading to a variety of outcomes in employment conditions. At the same time, the focus of this work was on small firms, and is seen to overemphasize conditions of subordination in supply chains (Ram, 1994). Subsequent studies exploring a broader range of sectors and inter-organizational relations have revealed greater complexity and variations in subordination and control between organizations, indicating a ‘tiering’ of relationships (Hunter, Beaumont and Sinclair, 1996). Moreover, such studies suggest that suppliers are not passive agents in such relationships, but actually contribute to their shaping (Turnbull, Oliver, and Wilkinson, 1992). In identifying factors that determine such outcomes, Sako’s (1992) study highlighted distinctions between organizational relations based on different types of contracts which were characterized as arms length (ALC) and obligational contracting (OCL), with each leading to differentiated employment outcomes, where the latter was more likely to favour employees (Marchington et al, 2005). However, while recognizing the continuing relevance of these insights recent contributions have adopted a useful multi-level analysis of the variations and causes in subordination and dependency. In particular, how institutional, organizational and interpersonal factors are inter-linked in shaping inter-organizational relations, and therefore employment outcomes (Marchington and Vincent, 2004: Marchington, et al, 2005: Vincent, 2005). In adopting such an approach this section makes a number of observations regarding possible causes behind variations in inter-organizational 6 relations between state and voluntary sector, and how these may shape employment outcomes in the latter. The institutional dimension To begin with the institutional dimension, the ongoing development of the quasimarket between voluntary sector and the state, is leading to coercive isomorphic pressures on the former (See Meyer and Rowan, 1977: DiMaggio and Powell, 1983). For example, the Care Commission has introduced care standards which are applicable throughout the sector and represent strongly institutionalized practices common to purchasers and providers so increasing the scope for control and subordination. In particular, the Commission has powers to introduce and amend standards of care provided to vulnerable groups across the UK, and also has powers of accreditation over the care workforce under National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs or SVQs in Scotland). For voluntary organizations the new care standards imply a significant degree of influence from external bodies over aspects of the labour process, especially worker flexibility around working time. This is because the care standards call for the delivery of more services on a twenty-four hour basis (see Cunningham, 2006 for summary). Yet complete subordination to external institutional pressures by voluntary organizations cannot be automatically assumed. Debates within institutional theory argue that resistance from voluntary organizations to state-sponsored isomorphic pressures is not uncommon (see Leiter, 2005 for summary). In particular, where voluntary organizations detect contradictions in their institutional fields they attempt to reach compromises and, therefore, complete isomorphism is not inevitable (Oliver, 7 1988). Moreover institutional links between organizations can be binding and encourage interdependence between organizations, rather than complete subordination of one party to the interests of another (Vincent, 2005). There is also a need to recognize that management’s decisions, and therefore the outcomes of organizational structure, policies, and working conditions, are not solely influenced by external isomorphic pressure, but also internal factors such as the employment relationship, where the dynamics of co-operation, conflict and resistance can determine the outcomes of management decisions (Friedman, 1977: Edwards, 1979: Thompson, 1983). Arguably, such resistance may emerge if, in response to institutional pressure, management in the voluntary sector follows similar strategies employed in public organizations where efforts to enhance workforce flexibility around working time run in parallel with attempts to erode the distinctions in payments between standard and unsocial hours (Beynon, Grimshaw, Rubery and Ward, 2002). In such cases where effective worker resistance emerges, either collective or individual, particular patterns of isomorphism around flexible working may not necessarily emerge. Organizational influences The second level in Marchington and Vincent’s (2004) framework, the organizational level can refer to the degree of (resource) dependency between organizations, which is shaped by factors including nature of the product, levels of income dependency, as well as organizational size. This literature highlights how these factors can be manipulated by supplier organizations to their advantage. For example, suppliers can be large-scale, powerful organizations in their own right that are less dependent on or 8 even have influence over the buyer. Explanations for this lack of dependence relate to supplier organizations having a monopoly over complex products or services, or delivering, consistently high quality services and/or innovation (Bresnen, 1996: Hunter, et al: 1996: Swart and Kinnie, 2003: Truss, 2004:). This is mirrored in some studies of the state - voluntary sector relationship where in a rural community there may be only one credible social care supplier or the more specialist and unique the service, the more likelihood there will be fewer suppliers who are in a relatively strong bargaining position with purchasers. This is seen as possible even within competitive markets as organizations build a specialist reputation in areas of service provision. Larger voluntary organizations are also seen as being able to manage markets more effectively and negotiate with purchasers on equal terms steering perhaps to more relational contracts (Johnson, Kendall, Bradshaw and Blackmore, 1998). In addition, it has also been argued that the position of the purchaser in the social care market is not as strong once a service is up and running with a contractor, given the disruption to services involved in changing providers (Mackintosh, 2000). Another application of the buyer-supplier literature that may be relevant is one that recognizes the complexity of contractual relations between parties beyond that outlined by Sako (1992). Individual organisations are seen as entering into different types of relationships with a multitude of partners, with suppliers themselves having relations with a variety of purchasers, characterized by varying degrees of dependency. Indeed, dependency may be confined to only specific aspects of the supplier’s operations and they can exhibit a degree of choice over whom to contract with, or 9 avoid difficult situations by exiting relationships (Blois, 2002: Bresnan, 1996: Hunter, et al, 1996: Blois, 2002). Interpersonal relations The third level of analysis concerns interpersonal relations or the activities of ‘boundary spanners’. For example, the expertise of those responsible for negotiating and monitoring contracts between organizations can be influential in shaping relations. In the context of public – private partnerships, it has been found that the latter can be in an advantageous position because they have personnel in post with extensive negotiating experience and skills (Marchington, Vincent and Cooke, 2005). Moreover, close personal, social ties between the parties can be influential in determining the nature of relations and foster interdependence rather than dependence and control (Blois, 2002: Williams, 2002: Marchington & Vincent, 2004: Truss, 2004). Interdependence between organizations built on personal relationships was identified by Osborne (1997) in his study of relationships between some local authorities and voluntary organizations. Here, relations were reciprocal, ongoing, interdependent, with parties sharing perspectives on social needs in their communities. The result of these relationships was that contracts were not decided on a strictly competitive basis, so leading to better outcomes for voluntary organizations (Osborne, 1997). The limitations to autonomy The above literature also suggests limitations to the exercise of autonomy across the three levels, which, again, may be applicable to the voluntary sector. For example, studies have found that exchanges between organizations change over time, reflecting 10 a range of factors including network composition, external pressures, reputation, costs and performance (Blois, 2002: Grimshaw and Rubery, 2005). Truss (2004), for example, observed a ‘negotiated order’ regarding inter-organizational relations within franchise arrangements which are eventually resolved in favour of the stronger party. It has also been found that several attributes in an inter-organizational relationship may be arms length in nature, while others are relational: suggesting relations between parties are a blend of the two. As a consequence, despite contracts being characterized as relational or ‘partnerships’, crucial aspects such as price may be subject to more transactional relations (Blois, 2002: Marchington et al, 2005). Therefore, terms and conditions of employment within suppliers may still suffer if the purchaser drives a hard bargain on price. Further, a reliance on strong interpersonal links to maintain good relations can be problematic. In particular, staff turnover in key boundary spanning roles can change relationships leading to a resort to formal terms of contracting as flexible cooperative practices are not passed onto new managers (Blois 2002: Marchington, Vincent and Cooke, 2005a). This is of some concern given tighter supervision and monitoring under such contractual relations has been shown to lead to incidences of deskilling and work intensification (Grugulis, Vincent and Hebson, 2003). These limitations to organizational autonomy in employment issues also imply constraints on the extent to which management can be persuaded or forced by workforce representatives to resist external pressure on pay etc. The role of unions in setting and maintaining pay and conditions may be limited in any event due to their 11 marginal presence in the voluntary sector, with union density estimated at 15 per cent (Unison, 2006). However, even where unions have a presence their ability to mobilize and protect workers’ terms and conditions may also be constrained. This is because it has been shown in studies from other sectors, that prospects for successful union campaigns are limited by the reality of power relations between purchaser – provider relations. Here, irrespective of union strength or management – labour relations, the capacity of external purchasers to dictate employment conditions to an employer is a crucial determining factor in union success (Marchington, Rubery and Lee Cooke, 2005b). Thus far, this paper has highlighted the potential for variation in inter-organizational relations between the state and voluntary sector and that this may have differential implications for employment outcomes in the latter. It also highlights factors at the institutional, organizational and inter-personal levels that may shape and determine these outcomes, and raised some caveats to these favourable outcomes. The remainder of the paper explores these issues in relation to their relevance to voluntary organizations and their ability to sustain public sector pay comparability and independence over the labour process in the face of cost based pressures exerted from state funding bodies. The paper now proceeds with an outline of the study’s methodology. METHODOLOGY This study involved an investigation of state – voluntary sector relationships and the subsequent impact on employment in twenty-four voluntary organisations based in 12 Scotland. They employed 13,500 employees, and provided a range of services for local authorities to vulnerable clients such as people with disabilities (eleven), children and young people (four), the elderly (three), or a combination of the above (six). Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with Personnel respondents from each organisation (twenty-two cases), or operational managers responsible for personnel issues (two cases). In nine organisations interviews were also conducted with managers responsible for negotiations with local authorities (eleven respondents). Supplementary information was gathered from participants relating to income, levels of dependency on government funding and workforce statistics. Table 1 reveals how among the twenty-four respondents there were varying degrees of dependency on state bodies for the funding of care activities, which have been placed in three broad bands. It can be seen that seven of the twenty-four were in Band A and solely dependent on state income for their care activities; eleven of the twentyfour were in Band B and dependent for between 80- 99% on state funding and the remaining six in Band C had between 50% to 79% of their incomes from this source. It is also worth noting that four of those that were funded entirely by the state outlined how local authorities were the exclusive source of state funding. Insert Table 1 here 13 Twelve representatives from seven unitary Scottish local authorities also participated in semi-structured interviews. These included two Heads of Social Service Departments, five Heads of Service; and five Contracting Officers. The selection of these organisations reflects the variety of care markets across Scotland, i.e. urban conurbations, suburban areas, areas embracing rural and urban constituencies; and a purely rural authority. The local authorities and voluntary organisations were chosen on the basis of having some form of contractual relationship with each other. It must be acknowledged that much of the data from the voluntary organisations and local authorities related to a wider range of contractual relationships. At the same time, the researcher also pressed for responses regarding specific issues and linkages between organisations. The findings are presented in three sections. The first provides a short context to interorganizational relations between purchasers and providers and in doing so also highlights differences in outcomes with regard to pay and conditions. It further argues that there are three Types of organization from among the twenty-four respondents differentiated by their ability to protect employment conditions in their workplace. The second, then proceeds to outline the strategies these organizations employ that go towards explaining these differences. The third proceeds to highlight the limits to the exercise of autonomy among the respondents. FINDINGS A variation in employment outcomes 14 All organizations reported a similar operating environment in the quasi-market, which was characterized by considerable pressure on pay and conditions and the labour process, e.g. through measures to intensify work and dilute skills in care teams. They also reported intensifying institutional pressures from the Care Commission and local authorities to provide twenty-four hour services to clients. Union strength among the respondents was uneven. Out of the thirteen unionized organizations in the study less than half (five cases) retained the link with local authority pay and conditions, and only two organizations reported union density above 50 per cent of the workforce. Several local authority participants were quite clear that this allowed them to exert pressure on voluntary sector pay and conditions because of the lack of strong collective bargaining in the sector. Each organization to varying degrees also highlighted the existence of contradictory pressures on pay and conditions from the labour market via wide-scale recruitment and retention problems. The above labour market and employment conditions occurred within a complex purchaser – provider environment. Respondents reported a predominantly financially insecure short-term (1 – 2 year) funding environment, where the move towards three year funding was slow in emerging and not consistent across purchasers. This resulted in voluntary organizations to varying degrees undertaking, sometimes multiple renegotiations of funding in any given year, complicated by individual projects being funded from different sources and requiring separate negotiations, with implications for management time and resources. For some, but not all organizations the failure to secure cost of living increases, or renewed funding, during these renegotiations would lead to services being cut back, and/or staff redundancies. 15 Additional costs on respondents would come from having to comply with contracts and service level agreements. This could prove to be difficult as negotiations around funding would sometimes result in cuts in the management and administrative expertise required to oversee these requirements. All organizations were constantly pursuing additional funding, which again involved significant management time and resources. This could involve a mixture of negotiated, fixed price or competitive scenarios with funders. It was noticeable that all voluntary sector respondents reported an increase in competitive tendering, although this was not universal across all purchasers. Yet, in response to these pressures, the data revealed far from homogenous outcomes with regard to employment conditions among the twenty-four respondents. For example, eleven of the twenty-four retained their link with local authority pay and conditions. There was also some variation in the capacity of voluntary organizations to resist local authority pressure on the labour process. This leads the paper to identify three types of voluntary organization among the twenty-four. As will be seen even within these types, there are degrees of vulnerability, and the potential for movement within and between them. Moreover, the paper is not claiming that these Types are applicable throughout the sector, or that others cannot be added, merely that for the purposes of this analysis they are useful. Type 1 – On the Inside Track Type 1 organizations (four respondents) – labeled ‘On the Inside Track’ although not immune to external pressures, represented the most successful group of respondents in terms of maintaining public sector pay and conditions. Moreover, although these 16 organizations were not immune to pressure on the labour process from local authorities, particularly the intensification of work within individual projects, there were more examples of resistance to such pressure. For example, one organization resisted efforts by local authorities to intensify the work of Support Assistants through adding some responsibilities that were part of the higher grade Support Worker role. This usually involved a parallel reduction in the numbers of Support Workers in projects, which, in turn, led to a dilution of expertise and skill in care teams. Another organization refused to employ Support Assistants because it was felt there was little difference between the Support Worker roles and simply represented a cheaper alternative. Local authorities reportedly encouraged these practices and were widespread in the sector, so the refusal of these organizations’ to comply was clearly going against the grain. Another of these organizations, in response to effective trade union resistance, withdrew proposals to cut unsocial hour’s payments to employees providing twentyfour hour coverage during Bank holidays despite pressure from the Care Commission and certain local authorities to significantly increase the numbers of staff working these flexible shift patterns. Again, other organizations would succumb to pressure to cut unsocial hours payments, so resistance was rare. There were several characteristics evident among these Type 1 organizations. In particular, they occupied Groups B and C income bands, and provided services nationally across the whole of Scotland, with two organizations also providing extensive services across the rest of the UK. Type 2 – Holding their own 17 Type 2 organizations (10 respondents), described as ‘Holding their own’ also contained some relative success stories with seven providing their staff with public sector pay and conditions, as well as examples of resisting external pressure on the labour process. In the latter case, again, one organization successfully prevented efforts to intensify the roles of Support Assistants. At the same time, some of these organizations did move away from public sector pay comparability, as well as report pressure on other conditions such as hours, holidays and unsocial hour’s payments. Among those that retained pay comparability, they were distinguished from Type 1 organizations by the fact that respondents reported how negotiations over the necessary funding increases were an annual struggle, with significant delays in implementing cost of living increases in wages due to protracted talks with local authorities. They were generally situated in Group B income band, and a majority provided services to most of the thirty-two Scottish local authorities, although four were providing to specific regions of Scotland. Type 3 – Struggling to Care Type 3 organizations – ‘Struggling to Care’ (10 respondents) had no examples of organizations following public sector pay comparability. These were the most vulnerable to efforts by external bodies to dilute skills, suffer from work intensification and continued pressures on pay and other conditions. In the majority of cases (7) they were situated in Group A income band (100% from state funders), and generally provided services to, at most, two or three local authorities rather than across the whole of Scotland. 18 In identifying the factors determining the capacity of these types of organization to resist external pressure on their pay and working conditions, the successful exercise of autonomy in employment issues was built on three core strategies being employed. These were: Taking advantage of product market/type of service and degree of competition; Developing a multi-customer base; and Utilizing voluntary sector finance and capital Moreover, the ability to apply these strategies was influenced by the aforementioned institutional, organizational and interpersonal level forces. The next section reveals in more depth the application of these strategies and their limitations. Taking advantage of product market/type of service and degree of competition With varying degrees of success, all respondents deployed their reputations as experts and innovators in delivering care to assist them in exercising autonomy over pay and working conditions. The deployment of expertise was also undertaken in a variety of different ways. Some were a reflection of situations where voluntary sector providers and local authorities recognized a degree of mutuality and interdependence more akin to OCL relations as outlined by Sako (1992). For example, Type 1 voluntary sector respondents appeared to have such a reputation and status with the majority of their local authority contacts that they were ‘On the Inside Track’ for certain funding 19 streams. In these circumstances, voluntary sector respondents could be in market conditions of, if not monopoly supply, then part of a few select potential providers that had specific expertise in an area of care and were invited to bid because they were part of an Approved Providers List (APL). These lists were quality checks by local authorities, which aided scrutiny of different policies among potential and actual contracting organizations, including some HR matters. Respondents also cited incidents where their organization, alone, would be approached to take on specific contracts, because of their reputations in dealing with the most challenging cases that other providers refused. A provider of adult services explained: We have no national competitor…We are seen as being a specialist provider, with a good track record and a national one. We are good at what we can do and we can demonstrate it, and we work very closely with local authorities. With very few exceptions, there have never been any issues with our credibility. In such situations, respondents reported how discussions over costs (including employment) were by negotiated agreement, i.e. a local authority would outline the type of service it wanted and both parties would have some input into the subsequent budget and staffing implications. This favourable status could also be supported by a strong marketing function within Type 1 organizations, with several actively promoting and aligning their services with 20 new funding streams. It was also reportedly supported by close, inter-personal relationships between ‘boundary spanners’ such as local authority decision-makers and senior management in voluntary organizations. This contrasted with experiences within Type 2 and 3 organizations, where relations between boundary spanners could be much more distant. The practical implications of this lack of links between ‘boundary spanners’ were highlighted by one respondent in a Type 2 organization who reported how: Personalities can have an impact. Some authorities we have very clear and direct links, we may not always get the answer we want but we know who to speak to. Some other local authorities, they wouldn’t actually speak to you, and that is the most frustrating aspect. People hide behind letters and e-mails. We will try wherever possible to bring people around the table, because it is a wee bit harder for them to look us straight in the eye and say ‘no we are not giving you it’. In addition, other divergences in influence between those ‘On the Inside Track’ and Type 2 and 3 respondents could be detected at the institutional level where some Type 1 organizations influenced national policy and practice. This was aided by advocacy and research facilities aimed at lobbying national and local government. Within these circumstances, respondents indicated how there was a greater acceptance by both sides of interdependence. Respondents further indicated that under this combination of circumstances, negotiations over pay were less difficult. 21 Again, differences between the three types of organization are worth highlighting. For example, several of the Type 2 organizations recognized the value in building such institutional influence, but progress in these organizations was merely in the planning stage. Partnerships with individual local authorities and Type 2 organizations were present, especially in the larger respondents, but these would be less common than in Type 1. For example, a respondent in a children’s services provider reported how her organization had one ‘true partnership’, with another developing, but the other relationships were distant with funding always subject to competition. Several Type 3 organizations illustrated how their relationships were far removed from such ‘partnerships’. For example, one respondent in describing the relationship with the organization’s key local authority funder stated: It is not a good or healthy relationship. It is very much one of control probably not valuing the organization as one that could contribute to the development of the community…there is very little partnership work around how to improve service. There are just lots of demands from the local authority that we need to look at our cost (Assistant Director of Service and Delivery). Another noted: I certainly don’t think we are partners, because you certainly can’t be equal if the person who has all the money makes all the decisions. This partnership thing everybody keeps talking about is just a load of toss. I think that we are 22 agents, as in ‘you will do this for us won’t you’, and we have the choice to turn it down, and I think that it is as good as it gets (Business Manager). It was among such Type 3 organizations that negotiated settlements over funding would be quite rare, with respondents facing in the vast majority of cases competitive or fixed price tenders, and during renegotiations of existing funding struggling to secure cost of living increases. The deployment of organizational expertise could also be used in more assertive ways in situations which did not necessarily reflect partnership relations. Local authorities claimed that larger, national voluntary organizations could be in quite a powerful position with purchasers, and relations could be far from the ideal of ‘partnership’. Large Type 1 and 2 organizations could employ this strategy of taking advantage of almost monopoly supply status. One local authority respondent commented: When they get the message that they are the only provider that is being asked to provide a particular type of service…they are smart enough to know that they have got them over a barrel and they have dictated, and that is where a big provider can have the upper hand, because they (local authorities) have got hospital closures and deadlines to meet. Sometimes a council has no choice (Commissioning Officer, local authority). Another strategy applied by all three types of voluntary organizations, to varying degrees of success, came through exerting influence via working together with similar organizations. The successful application of this strategy distinguished some of the 23 Type 2 and 3 organizations, i.e. several of the former reported successful joint lobbying of local authorities to protect their interests and retain autonomy over aspects of terms and conditions, while the latter were either unsuccessful or tentatively developing such links. The vulnerability of some funders to combined lobbying was confirmed by one local authority respondent in an area some distance from Scotland’s ‘central belt’ who noted how providers (one a Type 2 participant from this study) had successfully confronted her organization over payments for SVQ qualifications and were perceived to be very powerful, because of the general scarcity of alternative providers. The local authority respondent described these developments as ‘quite a thorny issue’. In an angry outburst she commented: Yes, they are quite a powerful body. They call themselves ‘the Forum’. Have you met the Forum? It’s a joy! Indeed, this respondent spoke of efforts within the authority to try and expand the market of providers to dilute this power. Such cases also illustrate the inter-linking between organizational factors, in these cases the size, scarcity of services and geography combined to create conditions where providers can work together as a counter to the power of the purchaser. It must also be noted that in the above case the issue itself was key to successful joint efforts to dilute the purchaser’s power, i.e. the common need for all providers to receive adequate resources to fund SVQ training. The identification of common ground among providers over such employment issues also appeared to be essential to contributing to such successful joint lobbying. 24 Developing a multi-customer base The second strategy, which was closely linked to the above, involved developing a multi-customer base across many of the thirty-two Scottish local authorities. For example, although some organizations had high levels of income dependence on specific contracts, it was not confined to one or two local authorities. As a consequence, larger organizations, among them Type 1 and some Type 2 respondents utilized financial surpluses built up from favorable contracts across the country to make up for shortfalls elsewhere and therefore avoided any detrimental impact on pay across the organization. For example, one Type 2 organization providing services for children and adults, utilized the favorable funding environment in the children’s services budgets to assist in maintaining uniform pay and conditions across the organization. At this juncture, it is useful to highlight the relative success or failure of union efforts to protect their member’s working conditions. For example, the aforementioned Type 1 organization that succumbed to a successful union campaign to protect unsocial hours payments did so not only in the context of rising union membership and activism, but management having the financial resources generated through surpluses built over eighty projects across Scotland to maintain current levels of pay. In contrast, within a Type 3 organization, a union’s efforts to protect its membership from pay cuts were thwarted despite an initial upsurge in members and activism. This was largely because the organization had no other choice, given it was solely dependent on one or two funders and therefore held insufficient financial surpluses to protect pay. 25 In addition, respondents reported that the stability gained from large-scale service provision gave them the ability to turn down contracts or close services if they felt their standards of care or terms and conditions of employment were being compromised. For example, two voluntary sector respondents had closed services in protest at successive cuts in local authority funding. In addition, several others reported how they would threaten to withdraw services if local authority negotiators persisted in attempting to push down employment costs. The success of such strategies also partly depended on whether particular local authorities were able to run the services, or if there were alternative voluntary or private sector organizations to take them over: again illustrating the inter-play with other causal factors such as competition. For several of these Type 2 organizations this strategy was central to their ability to maintain autonomy. One stated: The ultimate threat is calling off the service. So for us as an organization we turn around to a local authority and say ‘what are you going to do with twentyseven severely disabled people? So that is sanction and power, that is the biggest power we have as a negotiating tool (Care Services Director). Indeed, several voluntary respondents in Type 2 organizations were training their managers to be more assertive in negotiations with local authorities, with one reporting how managers were instructed to threaten the withdrawal of services when there was no intention of doing so: the aim being to get the local authority negotiators to ‘blink first’. This latter point suggests that some providers were paying increasing 26 attention to the potential influence from organizational, ‘boundary spanning’ agents as a tool in defending their interests. Similarly, several Type 1 and 2 organizations were also refusing to be part of purchasers’ plans by not applying for new contracts. This was a deliberate strategy where providers were asked to deliver a service on the basis of a fixed price. Their decision not to bid was based on several factors. The first being the rejection of an unrealistic fixed price that would not adequately cover staffing costs or provide a sustainable quality of provision to service users. In addition, the respondents wanted to send signals to funders that their organizations had independence, with one head of services stating: ‘I want local authorities to get the message that it’s harder. You do not just snap your fingers and we will jump..we don’t need the business.’ A key factor in underpinning this ability was the fact that voluntary sector providers had built up significant resources from other contracts so the closure of a service or a refusal to take on business would not threaten the survival of the organization, and staff could be redeployed elsewhere. One Type 2 respondent reported how, in order to facilitate this, it was increasingly becoming essential for his service managers to network with a variety of local authority contacts in order to promote the organization for future contracts. This contrasts with other organizations, predominantly in Type 3, that provided services to only a few purchasers and within a relatively narrowly defined geographic 27 area, with a number of other suppliers available as competitors. Here, respondents spoke of the ongoing vulnerability of their organizations to the cost pressures on pay and conditions from one or two key purchasers, where negotiations were distant and mainly on the basis of either fixed price or competitive. Indeed, some of these were actively seeking other sources of income to offset this vulnerability. Moreover, they were not all exclusively small to medium sized. For example, one employed over seven hundred staff, while another, three hundred, but management respondents revealed how each organization’s location and reliance on only a few funders made them vulnerable. Utilizing Voluntary Finance and Capital A more controversial resource was the use of voluntary income as a contribution to build ‘partnerships’ around particular care packages: with some organizations making financial contributions of between 10% - 25%. This income was sourced from financial reserves held by organizations, fundraising activities, or the provision of a purpose-built or renovated building. Three Type 1 (all children’s services) and one Type 2 (children and adult services) respondent(s) saw advantages in this approach, through the belief that part funding, or contributing added value would offset any reservations the funder had about expensive bids. It was also felt that it gave respondents a better chance of a voice in decisions about the shape of specific services, and some freedom of manoeuvre regarding issues such as pay and conditions. The ability of organizations to raise extra capital was, in some, but not in all cases, also inter-linked with another of these causal factors – i.e. the type of services that 28 were being delivered. In particular, respondents caring for children and young adults were more successful at raising extra finance compared to organizations that were in the field of adult care. Respondents from local authorities and the voluntary sector suggested that other funding bodies, such as the Scottish Executive and the general public were more susceptible to support causes in the field of children and young people than in services for vulnerable adults. The limits to autonomy Despite, the above, it was clear that respondents’ ability to resist local authority interference in employment issues was constrained by several factors outlined below. Service closure and its associated problems Although a useful strategy, there were clearly limits to voluntary organization efforts to encourage boundary spanners to be tougher in negotiations with local authorities over the price of contracts. This relates to voluntary organizations being associated with the closure of services in the face of consistent cuts in funding that effected quality of care and pay and conditions. The two respondents who engaged in closing services did acknowledge that these decisions were followed by extremely bad publicity, so this would arguably be a decision of the last resort. Others revealed problems and complexity associated with subsequent transfers of employment after closure once organizations withdrew from service provision and another provider took over. These concerns were associated with meeting the requirements of the Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) 29 Regulations, 1981 (TUPE). These regulations (subsequently amended through the Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) Regulations, 2006) originate from European Union requirements and are in place to preserve employees’ terms and conditions when a business or part of one, is transferred to a new employer (DTI, 2007). In addition, they revealed potential problems with morale among remaining employees when services were closed and colleagues left the organization through redundancy, turnover or TUPE. Uneven partnership arrangements The rhetoric of ‘partnership’ was used during interviews by both sides to describe their relationship, yet even where such circumstances reportedly existed there were imbalances. For example, the strongest advocate of contributing internal resources to projects was from a large children’s voluntary organization that provided funding for all its projects (Also in Type 1 category). Yet, the respondent revealed that all this contribution gave the organization was a ‘junior partnership’, and that local authorities remained dominant. In addition, several respondents pointed out how relations with authorities contained different attributes so that the rhetoric and practice of partnership was present in some aspects, but on financial issues relations were more transactional. A local authority confirmed this by stating: The bottom line is that it’s an uneven partnership. The negotiation is uneven. When we are holding the budgets and where we are the purchasing authority, it’s an uneven partnership and that is difficult for them to grasp. 30 This was confirmed by respondents from the sector. For example, a Development Coordinator in a Type 2 organization stated: When local authorities tell us to jump, we say ‘how high?’. They try and be partners and talk of a partnership, but to be honest there are all sorts of power issues involved. There was also evidence of coercion on voluntary organizations to make contributions from internal resources. There were several respondents in the Type 2 organizations that involuntarily drew from reserves to support pay and conditions and other aspects of service delivery. HR and non-HR respondents from these organizations reported a reluctance to draw on their reserves because they felt that, in effect, they were indirectly subsidizing central and local government initiatives with internal income that was not specifically earmarked for care. Yet, these same respondents felt they had little choice if they wished to remain in the care market and pay decent salaries. One or two were able to avoid this by having a clear policy of not putting ‘partnership’ funds into contracts that involved some statutory responsibility of the local authority, but again this was limited to those (Type 1 and some Type 2 organizations) that were able to turn down, or insist on full state funding of such work because they were in a relatively strong and secure position. Several of the respondents who were subsidizing particular projects noted how this was becoming a serious drain on their reserves, and were going into deficit. One of these, a Hospice, was going into financial deficit because of its need to retain NHS trained staff, and was undertaking joint lobbying of NHS/local health authority 31 representatives with other Hospices for more funding. This strategy was employed largely because staff retention problems were too intractable to be coped with on an individual organizational level so joint sub-sector lobbying was needed. Some local authority respondents expressed little sympathy with these complaints, and saw the use of additional capital as a prerequisite of gaining contracts that helped voluntary organizations fulfill their own internal missions and objectives and was the price to be paid. One Head of Social Work stated: If they think there is a solution where local authorities are going to say ‘oh yes we want every voluntary organization in the country to have massive reserves and we will be happy to empty our coffers into their’s so that they all sit with it’ is a bit unrealistic. A renegotiation of order Further illustrations of the limits of autonomy came from examples of a renegotiation of order between voluntary organizations and funding partners. The latter part of the fieldwork involved undertaking three in-depth case studies. Two of these organizations were in relatively strong positions in the market in 2002, yet by 2004 were experiencing, to varying degrees, a renegotiation of their relationship. One of these, a Type 1 organization, given the pseudonym Universal, illustrates this phenomenon. Universal delivered children’s services and in 2002 the Personnel Manager outlined the organization’s position as a provider of choice, making financial contributions to 32 projects where it had partnerships with local authorities in non-statutory services. It had effective boundary spanning agents who had close links with local authority contacts and was actively attempting to be more proactive in lobbying government with regard to future legislation and funding streams. However, interviews in 2004 revealed a deteriorating position. The Finance Director reported that, although some authorities still approached them to undertake work, others were increasingly putting services out to competitive tender. Moreover, recent turnover in internal staff and within some local authorities meant the links between various ‘boundary spanners’ had disappeared: a situation Universal had been slow to recover from. Alongside this, it was felt that its efforts to attract funding in more competitive circumstances were undermined by the cost of the organization’s bids and its lack of ‘slickness’ compared to competitors. Moreover, doubts emerged regarding the benefits of making financial contributions to ‘partnership projects’ and how much additional voice it gave the organization with purchasers. In 2004, the Finance Director who had some responsibility for overseeing negotiations in many of the projects stated: There is a marginal benefit in that we can say that if there is an element of the service that isn’t doing precisely what the local authority wants us to do then we can say ‘that is our bit of funding’. But to be honest that is a bit of a marginal argument…on the whole the voluntary funds we put in aren’t appreciated as much as the pound value of them. 33 There was also some evidence to suggest that funders were beginning to circumvent government licensing conditions regarding having certain qualified staff in place to provide services. Providers reported how for certain services to be delivered, they were obliged to employ qualified staff such as social workers or teachers, and pay the necessary salaries that were comparable with the public sector. However, here several providers reported how during renegotiations of contracts in order to cut costs, purchasers were reportedly recommending that fewer ‘qualified staff’, should be employed. Respondents expressed some concern regarding the impact this had on the quality of care as more unqualified staff provided a lesser service. Other respondents were concerned that in some services there was the risk that the boundaries between ‘qualified’ and ‘unqualified’ were being blurred and that, as a result, they were monitoring changes in contract specifications to ascertain whether unqualified members were being asked to take on the responsibilities of qualified workers. In addition, more recent evidence gained through the author’s ongoing contacts with participants after the study suggested local authorities were beginning to counter efforts by voluntary organizations to exercise autonomy. For example, one participating Type 2 organization revealed how the strategy of refusing work was becoming more difficult. The respondent revealed how another agency had withdrew from a service because of the imposition of a 10 per cent cut in funding by a local authority. Representatives from the same authority then approached the respondent’s organization to tender for the contract at this reduced fixed price. Initially, this organization refused to tender, but in response, the local authority threatened that if it did not, it would be removed from its APL, resulting in a bid by the respondent to 34 take on the services: albeit other sources have subsequently commentated that this was not the most rigorous or realistic bid this organization had submitted for scrutiny. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION This paper has explored the degree of variation in state – voluntary sector interorganizational relations and its outcomes in terms of the employment relationship in the latter. In doing so, it reveals how the voluntary sector’s relationship with the state is not so dependent as to mitigate the possibility of exercising autonomy with regard to the management of the internal employment relationship. Rather, as with broader studies of inter-organizational relations, state – voluntary sector relations are not homogenous and lead to differing implications for employment (Hunter, et al, 1996). Three types of voluntary organizations were identified according to the degree of control and subordination in their relations with funders. Across the three types, over and above the impact of unionization, success in protecting pay and conditions appeared to be dependent on the application of three strategies – i.e. taking advantage of product market/type of service and degree of competition; developing a multicustomer base; and utilizing voluntary sector finance and capital. The successful application of these strategies was shaped by institutional, organizational and inter-personal factors. Type 1 organizations - ‘On the Inside Track’ were able to apply the three strategies most successfully through a combination of an advantageous position in the market associated with type of service, income dependency, size and geography, underpinned by a capacity to partially influence their institutional environments through lobbying, marketing and close inter-personal 35 relations. This contrasted with Type 2 and 3 organizations - ‘Holding their Own’ and ‘The Strugglers’ , where although some of the former retained pay and conditions comparability, weaker influence over their institutional environment, looser links between boundary spanners and the majority of contracts with funders being subject to competition, meant greater degrees of vulnerability and subordination in their relations with local authorities. Across Type 1 and 2 organizations, size also appeared to offer some advantages. Specifically, as with other studies (see Hunter et al, 1996), larger Type 1 and 2 organizations were able to successfully forge more equitable relationships, or they refused to take on specific contracts, and/or exited services early if pressure from funders became too intense. At the same time, this study revealed other strategies for survival emerging from the sector such as the larger organizations able to generate surpluses from OCL relations to subsidize less favourable contracts and training boundary spanners to be more assertive in negotiations. The study also confirmed limits to the exercise of autonomy. As with other studies (Blois, 2002: Marchington, Vincent and Cooke, 2005a), the influence of boundary spanners, more assertive or not, was insufficient on their own to sustain autonomy, or could be subject to deterioration. The data also revealed how relations between purchasers and providers were not always characterized in strict relational/transactional terms, but could be a blend of each attribute. Here, as with research by Blois (2002) despite some relations being described as ‘partnership’ issues of price could be a transactional attribute to the contract. In such cases, this appeared to undermine the efforts of even those ‘On the Inside Track’ to use the 36 rhetoric of ‘partnership’ and additional funding to give them a stronger voice in their relations with local authorities. Of further concern was the evidence revealed in this study of how some Type 2 organizations felt coerced into subsidizing services by drawing from their own reserves, placing doubts over the extent to which they could ‘hold their own’ in the future. There was also the possibility of movement and deterioration in status within the three types of voluntary organization. Certainly, evidence from some respondents confirmed this, largely supporting work by Truss (2004) who argues that the ‘negotiated order’ of inter-organizational relations can sometimes benefit the weaker ‘partner’, but inevitably constant renegotiation of that order resolves relations in favour of the more powerful party. While acknowledging the limits of the applicability of this exploratory study throughout the sector, there are some lessons to be drawn. In terms of theorizing voluntary sector – state relations it suggests a need to move away from the dichotomy of ‘partnership’ versus ‘control and subordination’. Rather, it sees the state – voluntary sector relationship, like other inter-organisational relations as dynamic where the weaker party can, under certain conditions, manage the relationship and exercise influence and autonomy. Moreover, it acknowledges the possibility of movement, albeit partial, across a continuum rather than identifying three set organizational Types. Further, it is acknowledged that further research would be welcome to further refine existing and perhaps identify other Types. 37 The above analysis also raises questions regarding the wider applicability of the study. The first question relates to the study’s wider applicability beyond Scotland to the UK context. There is continuing debate as to whether there has been a departure from the rest of the UK and the creation of a distinctive post-Devolution social welfare policy in Scotland (Mooney and Poole, 2004: Vincent and Harrow, 2005), which is beyond the scope of this paper. However, with regard to differences in employment issues, although not specifically focusing on the theme of this paper, a recent study sponsored by the public sector union Unison, has explored purchaser - provider relations across the UK. In doing so, it uncovered evidence of similar financial constraints characterizing such relations, pressure on terms and conditions, and voluntary organizations responding to this environment by adopting some of the strategies outlined in this study (Cunningham and James, 2007), suggesting some degree of wider applicability to these findings in the UK. Further, there are also similarities with the wider voluntary sector literature. For example, in the UK, there is a literature which highlights how voluntary organizations develop competitive advantage from addressing specific niche markets (Billis and Glennerster, 1998). Moreover, studies from the USA have also attempted to analyze the diversity of non-profit organizations subject to contractual relations with the state. In one study, although the Types of organization are not identical to the three outlined here, there are striking similarities with regard to the strategies adopted by non-profits in the USA to resist impositions of government. In particular, this study emphasized the importance of US nonprofits to adopt strategies such as delivering difficult or niche services, refusing to apply or reapply for specific contracts and lobbying through umbrella organizations (Lipsky and Smith, 1989). 38 Finally, in terms of answers to the problems faced by the sector in its relations with the state, this paper offers no easy solutions for the voluntary organizations in the UK or in other Western industrialized countries where similar inter-organizational dynamics occur. There are many interests in and around the sector that are proposing changes to the funding process and cycle between the parties that are worth lobbying for at sector level (see for example, ACEVO, 2004: Gershon, 2004: Amicus, 2006). However, most reports suggest that even central government-led reform such as the move towards ‘full cost recovery’ is at best slow in making progress in favour of the voluntary sector (National Audit Office, 2005). A failure by voluntary organizations to not attempt to proactively manage the relationship with the state in some way that focuses on their roles as innovators, or to diversify their funding is potentially disastrous. The aforementioned report (Cunningham and James, 2007) suggested further intensified competitive and cost pressures in the sector due to the introduction of the Public Contracts Regulations 2006 (Public Contracts (Scotland) Regulations 2006) which have been introduced as a consequence of the Public Contracts Directive 2004/18/EC. Arguably, this and the pressures outlined in this paper threaten to move the state – voluntary sector relationship to something approaching a commissioning model, where the grounds for funding voluntary organizations are primarily instrumental, i.e. focusing on the cost effective completion of specific tasks which does not emphasize the flexibility, innovativeness and client focused aspects of third sector service provision. Arguably, for the most vulnerable organizations these cost and competitive dynamics may lead to their long-term position as providers in the quasi-market open to doubt. For those 39 remaining, the findings raise real concerns about the possibility of slipping down the tiering or continuum of types of voluntary organization populating the market. If this were to occur there would be long-term consequences for staff morale and therefore quality of care provided by the sector. Acknowledgements The author would like to thank the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland for part funding this project, and acknowledges the extremely constructive comments of the three anonymous referees. References Alatrista, J and Arrowsmith, J (2004) “Managing Employee Commitment in the notfor-profit sector”, Personnel Review, 33 (5), 536 – 548. Amicus (2006) Short- term funding, Short-term thinking, London. ACEVO (Association of Chief Executives of Voluntary Organizations) (2004) “Surer Funding”, ACEVO Commission of Inquiry Report, London, November. Barnard, J, Broach, S and Wakefield, V (2004) Social Care: the growing crisis, Report on Recruitment and Retention Issues in the Voluntary Sector by the Social Care Employers Consortium, London. 40 Beynon, H, Grimshaw, D, Rubery, J and Ward, K (2002) Managing Employment Change: The New Realities of Work, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Billis, D and Glennerster, H (1998) “Human Services and the Voluntary Sector: Towards a Theory of Comparative Advantage”, Journal of Social Policy, 27, (1), 7998. Blois, K (2002) “Business to business exchanges: a rich descriptive apparatus derived from MacNeil’s and Menger’s analyses’, Journal of Management Studies, 39 (4): 523-51. Bresnen. M (1996) “An Organisational Perspective on Changing Buyer-Supplier Relations: A Critical Review of the Evidence”, Organization, 3 (1), 121-146. Cunningham. I (2001) “Sweet Charity! Managing employee commitment in the UK voluntary sector, Employee Relations Journal, 23 (3), 226-240. Cunningham, I (2005) Struggling To Care: Voluntary Sector Work Organization And Employee Commitment In The Era Of The Quasi-Market, unpublished Phd thesis, University of Strathclyde. Cunningham, I and James, P (2007) False Economy? The Costs of Contracting and Workforce Insecurity in the Voluntary Sector, Unison, London, May. 41 DTI (Department of Trade and Industry) (2007) “The Transfer of Undertakings Regulations”, www.dti.gov.uk/employment/trade-union-rights/tupe/, accessed 5.2.07. DiMaggio. P.J and Powell. W.W (1983) “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organisational fields”, American Sociological Review, (35), 147-160. Edwards, R (1979) Contested Terrain: The Transformation of the Workplace in the Twentieth Century, Heineman, London. Friedman, A (1977) Industry and Labour: Class Struggle at Work Monopoly Capitalism, London, Macmillan. Gershon, P (2004) Releasing Resources for the Frontline: Independent Review of Public Sector Efficiency, HM Treasury, London, July. Grimshaw, D and Rubery, J (2005) “Inter-capital relations and network organization: redefining the work and employment nexus”, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 29 1027-51. Grugulis, I Vincent, S and Hebson, G (2003) ‘The rise of the ‘network organization’ and the decline of discretion’, Human Resource Management Journal, 13, (2) 44-58. Harris. M (2001) “Voluntary Organisations in a Changing Social Policy Environment”, in Harris. M and Rochester. C (eds), Voluntary Organisations and 42 Social Policy in Britain: perspectives on change and choice, Palgrave, Houndmills, Basingstoke, pp. 213-228. Hunter, L, Beaumont, P and Sinclair, D (1996) “A Partnership Route to HRM”, Journal of Management Studies 33 (2), 235-257. Jas, P, Wilding, K, Wainwright, S, Passey, A and Hems, L (2002) The UK Voluntary Sector Almanac, NCVO publications, London. Kendall, J (2003) The Voluntary Sector, Routledge, London. Knapp. M, Hardy. B and Forder. J (2001) “Commissioning for quality: ten years of social care markets in England”, Journal of Social Policy, 30 (2): 283-306. Johnson, N, Jenkinson, S, Kendall, I, Bradshaw, Y, Blackmore, M (1998), “Regulating for Quality in the Voluntary Sector”, Journal of Social Policy (27), 3, pp. 307-328. Leiter, J (2005) “Structural Isomorphism in Australian Nonprofit Organizations”, Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 16 (1), 1 – 31. Lipsky, M and Smith, S (1989) “Nonprofit Organizations, Government, and the Welfare State”, Political Science Quarterly, Winter, 625-649. 43 Mackintosh, M (2000) “Flexible Contracting? Economic Cultures and Implicit Contracts in Social Care”, in Journal of Social Policy, (29), 1, 1 – 19. Marchington, M, Grimshaw, D, Rubery, J and Willmott, H (2005) Fragmenting Work: Blurring Organizational Boundaries and Disordering Hierarchies, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Marchington, M and Vincent, S (2004) “Analysing the Influence of Institutional, Organizational and Interpersonal Forces Shaping Inter-Organisational Relations”, Journal of Management Studies, 41 (6): 1029-56. Marchington, M, Vincent, S and Cooke, F.L (2005a) “The Role of BoundarySpanning Agents in Inter-Organizational Contracting”, in Marchington, M, Grimshaw, D, Rubery, J and Willmott, H (eds) Fragmenting Work: Blurring Organizational Boundaries and Disordering Hierarchies, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 135 156. Marchington, M, Rubery, J and Lee Cooke, F (2005b). “Prospects for Worker Voice Across Organizational Boundaries”, in Marchington, M, Grimshaw, D, Rubery, J and Willmott, H (eds) Fragmenting Work: Blurring Organizational Boundaries and Disordering Hierarchies, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 239-260. 44 McClimont, B and Grove, K (2004) Who Cares Now: An Updated Profile of the Independent Sector Home Care Workforce in England, United Kingdom Home Care Association, Carshalton, Surrey. Meyer. J.W and Rowan. B (1977) “Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony”, American Journal of Sociology, 83 (2), 340- 363. Mooney, G and Poole, L (2004) “A land of milk and honey? Social policy in Scotland after Devolution”, Critical Social Policy, 24 (4), 458-483. National Audit Office (2005) Working with the Third Sector, London, June. Newman, J, 2001, Modernising Governance: New Labour, Policy and Society, (Sage, London). Oliver. C (1988) “The Collective Strategy Framework: An Application to Competing Predictions of Isomorphism”, Administrative Science Quarterly, 33, 543-561. Osborne, S.P (1997) “Managing the Coordination of Social Services in the Mixed Economy of Welfare: Competition, Cooperation or Common Cause?”, in British Journal of Management, 8, 317-328. 45 Perri 6 and Kendall. J (1997) “Introduction”, in Perri 6 and Kendall. J (eds) The Contract Culture in Public Services, Arena, Ashgate, Aldershot, 1-15. Rainnie, A (1989), Industrial Relations in Small Firms: Small Isn’t Beautiful, London: Routledge and Kogan Page. Rainnie, A (1992) “The reorganization of large firm contracting: myth and reality”, Capital and Class, 49, 53-75. Ram, M (1994) Managing to Survive – Working lives in small firms, Oxford, Blackwell. Remuneration economics (2002) 15th annual Voluntary Sector Salary Survey. http://www.celre.co.uk. Roper, I, Prabhu, V and Zwanenberg, N.V (1997) “(Only) just-in-time: Japanisation and the “non-learning” firm”, Work Employment and Society, 11, (1), 27-46. Russell, L, Scott, D and Wilding, P, (1996) “The Funding of Local Voluntary Organisations”, Policy and Politics, 24, (4), 395-412. Sako, M (1992) Prices, Quality and Trust: Inter-firm relations in Britain and Japan, Cambridge University Press. 46 Scottish Centre for Employment Research (2005) Something to believe in: A report on recruitment problems and opportunities in the Scottish Voluntary Sector, University of Strathclyde. Shah, R (2004) Labour Market Information Report, Edinburgh, SCVO. Swart, J and Kinnie, N (2003) “Knowledge intensive firms: the influence of the client on HR systems’, Human Resource Management Journal, 13: 3 37-55. Thompson, P (1983) The Nature of Work: An Introduction to Debates on the Labour Process, Macmillan, London, 153-176. Tonkiss, F & Passey, A (1999) “Trust, Confidence and Voluntary Organisations: Between Values and Institutions”, Sociology, 33 (2), 257-274. Truss, C (2004) “Whose in the Driving Seat Managing Human Resources in a Franchise Firm”, Human Resource Management Journal, (11) 4, 3-21. Turnbull, P, Oliver, N and Wilkinson, B (1992) ‘Buyer-supplier relations in the UK automotive industry: strategic implications of the Japanese manufacturing model’, Strategic Management Journal (13), 159-68. Turnbull, P, Delbridge, R, Oliver, N and Wilkinson, B (1993), “Winners and losers. The ‘tiering’ of component suppliers in the UK automotive industry’, Journal of General Management, (19), 1, 48-62. 47 Unison (2006) www.unison.org.uk/voluntaryindex. accessed 19.5.06. Vincent, S (2005) “Really dealing: a critical perspective on inter-organizational exchange networks”, Work, employment and society, 19 (1), 47-65. Vincent, J and Harrow, J (2005) “Comparing Thistles and Roses: The Application of Governmental-Voluntary Sector Relations Theory to Scotland and England”, Voluntas, 16 (4), 375-395. Wainwright, S, Clark, J, Griffith, M, Jochum, V and Wilding, K (2006) The UK Voluntary Sector Almanac 2006, NCVO publications, London. Warhurst, C (1997) “Political Economy and the Social Organisation of Economic Activity: A Synthesis of Neo-Institutional and Labour Process Analysis”, Competition and Change, 1997, 2, 213-246. Wilding, K, Collins, G, Jochum, V and Wainright, S (2004), The UK Voluntary Sector Almanac 2004, NCVO Publications, London. Wilding, K, Collis, B, Lacey, M and McCullough, G (2003) Futureskills 2003: A skills foresight research report on the voluntary sector paid workforce, NCVO, London. 48 Williams, P (2002) “The Competent Boundary Spanner”, Public Administration, 80 (1), 103-24. 49