Ecological health effects of mercury

advertisement

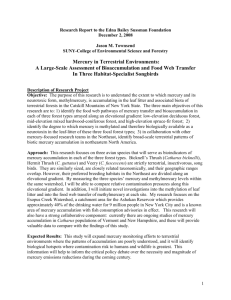

Ecological health effects of mercury Most of the attention around mercury focuses on lakes and other aquatic ecosystems (rivers, streams, wetlands and oceans). This is due to the fact that the levels of mercury usually found in terrestrial environments are not high enough to represent a threat to the health of wildlife or humans. However, humid environments such as wetlands and lakes favor the transformation of mercury into its most poisonous form, methylmercury which exhibit toxic effects at much lower concentrations. The presence of methylating bacteria and living organisms, that will initially absorb methylmercury in their food diet, then creates proper conditions for the bioaccumulation of methylmercury in fish communities. Many species of fish and wildlife, which rely on fish for food, become at risk of mercury poisoning. Otters, loons, minks and osprey are all examples fish-eating species in Canada that might be in danger. Loons have been studied extensively so that scientists can learn more about the effects of mercury on species with a high fish diet, as well as to determine whether mercury is harming loons. Many loons in eastern Canada and the northeastern United States have high mercury levels that are causing serious reproductive and behavioral problems. The presence of mercury in hydro reservoirs has been a serious issue in northern Canada, and particularly in Quebec, where some of the world’s largest hydro reservoirs are located. Large hydro reservoirs that flood hundreds or thousands of square kilometers of forest become the perfect habitat for mercury methylation to occur. The decomposing forest creates an ideal environment for microorganisms to convert the natural mercury in soils, together with the mercury deposited by human activities, into methylmercury. The methylmercury accumulates in aquatic species, making certain fish unsafe to eat for wildlife and humans for several decades after impoundment.