Use Topoi to Generate Topics and Organize Your Essay

advertisement

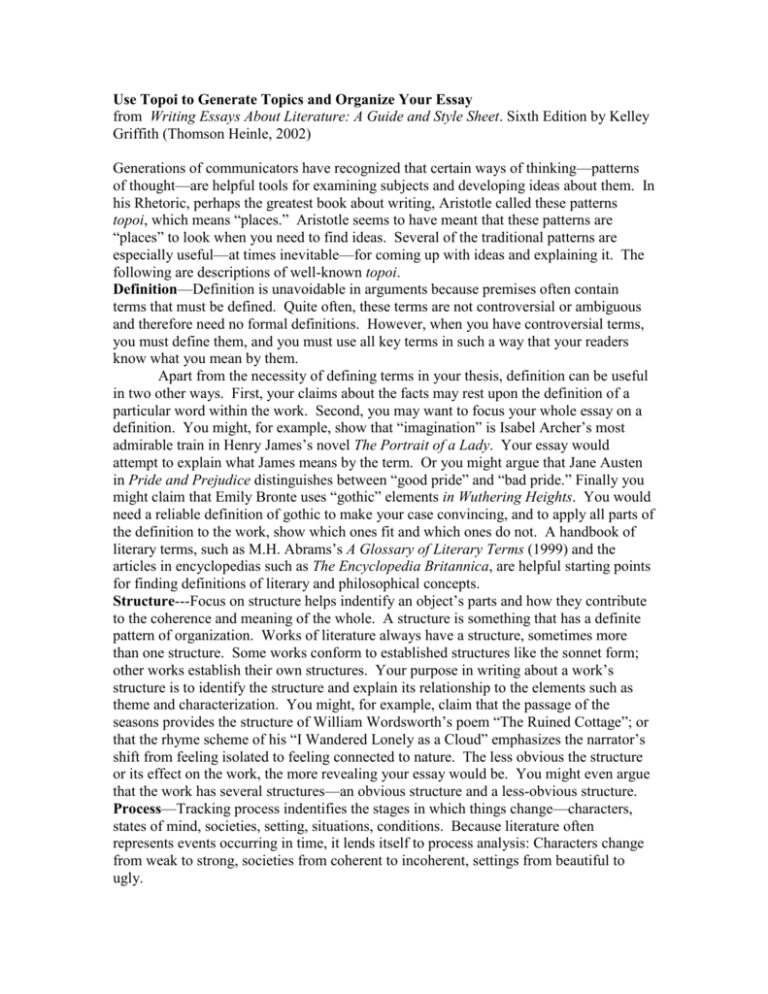

Use Topoi to Generate Topics and Organize Your Essay from Writing Essays About Literature: A Guide and Style Sheet. Sixth Edition by Kelley Griffith (Thomson Heinle, 2002) Generations of communicators have recognized that certain ways of thinking—patterns of thought—are helpful tools for examining subjects and developing ideas about them. In his Rhetoric, perhaps the greatest book about writing, Aristotle called these patterns topoi, which means “places.” Aristotle seems to have meant that these patterns are “places” to look when you need to find ideas. Several of the traditional patterns are especially useful—at times inevitable—for coming up with ideas and explaining it. The following are descriptions of well-known topoi. Definition—Definition is unavoidable in arguments because premises often contain terms that must be defined. Quite often, these terms are not controversial or ambiguous and therefore need no formal definitions. However, when you have controversial terms, you must define them, and you must use all key terms in such a way that your readers know what you mean by them. Apart from the necessity of defining terms in your thesis, definition can be useful in two other ways. First, your claims about the facts may rest upon the definition of a particular word within the work. Second, you may want to focus your whole essay on a definition. You might, for example, show that “imagination” is Isabel Archer’s most admirable train in Henry James’s novel The Portrait of a Lady. Your essay would attempt to explain what James means by the term. Or you might argue that Jane Austen in Pride and Prejudice distinguishes between “good pride” and “bad pride.” Finally you might claim that Emily Bronte uses “gothic” elements in Wuthering Heights. You would need a reliable definition of gothic to make your case convincing, and to apply all parts of the definition to the work, show which ones fit and which ones do not. A handbook of literary terms, such as M.H. Abrams’s A Glossary of Literary Terms (1999) and the articles in encyclopedias such as The Encyclopedia Britannica, are helpful starting points for finding definitions of literary and philosophical concepts. Structure---Focus on structure helps indentify an object’s parts and how they contribute to the coherence and meaning of the whole. A structure is something that has a definite pattern of organization. Works of literature always have a structure, sometimes more than one structure. Some works conform to established structures like the sonnet form; other works establish their own structures. Your purpose in writing about a work’s structure is to identify the structure and explain its relationship to the elements such as theme and characterization. You might, for example, claim that the passage of the seasons provides the structure of William Wordsworth’s poem “The Ruined Cottage”; or that the rhyme scheme of his “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” emphasizes the narrator’s shift from feeling isolated to feeling connected to nature. The less obvious the structure or its effect on the work, the more revealing your essay would be. You might even argue that the work has several structures—an obvious structure and a less-obvious structure. Process—Tracking process indentifies the stages in which things change—characters, states of mind, societies, setting, situations, conditions. Because literature often represents events occurring in time, it lends itself to process analysis: Characters change from weak to strong, societies from coherent to incoherent, settings from beautiful to ugly. When describing a process, avoid simple retelling the plot. Instead, explain and illustrate clear steps in the overall process. Present them in the order in which they occur in time. Each step would be a unit—probably a paragraph—of your paper. The claim of each unit would be your proposition about what characterizes the step. Cause and effect—Examining cause and effect helps you investigate the causes and effects of things. When you investigate causes, you are always dealing with things in the past. Why does Goodman Brown go into the forest? Why does Hedda Gabbler act the way she does? What causes Pip to change? Two kinds of causes usually figure in the works or literature, the immediate or surface cause and the remote or deep cause. In Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy, the immediate cause of Roberta Alden’s death is that she is pregnant. Clyde Griffiths kills her because he wants her out of the way so he can marry Sondra Finchley. The remote cause, however, is all those forces— childhood experiences, parental models, heredity, financial situations, cultural values, religious background, and accident—that have molded Clyde and that make the reasons he kills Roberta complex. When you investigate effects, you may deal with things in either the past or the future. In William Faulkner’s fiction, you might examine the effect of slavery on Southern society and on his characters. These effects are part of the historical past in his work. You might also predict what the South will be like in the future, given the way he depicts it. Because literature often deals with the actions of complex characters and societies, analyzing cause and effect is a fruitful source of essay topics. We constantly wonder why characters do what they do and what effects their actions have had or will have. Just as in real life, cause and effect in literature can be subtle. Your task is to discover and communicate those subtleties. Comparison—Comparison means indicating both similarities and differences between two or more subjects. One us of comparison is to establish the value of something. You might argue that one of Shakespeare’s comedies is not as good as the others because it lacks some of the qualities the others have. Another use of comparison is to explain your insights about aspects of a work. A comparison of the two sets of lovers in Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, for example, helps us understand his distinction between sacred love and profane love. Comparing the theme of one work to another is also revealing. Sir Walter Raleigh’s poem “The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd” is a response to Christopher Marlowe’s “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love.” Raleigh not only disagrees in general with the premise of Marlowe’s poem, he also makes nearly every line of the poem respond to the parallel line in Marlowe’s poem. A line-by-line comparison of the two poems helps make Raleigh’s themes clear. Comparison is revealing also when the author of a work contains allusions. An allusion is a reference to another work, historical event, a myth, or an author. An allusion is always an invitation to compare the work at hand to the thing alluded to. Wordsworth, for example, in his long autobiographical poem The Prelude often alludes to Milton’s Paradise Lost. One could compare The Prelude and Paradise Lost to clarify Wordsworth’s methods and themes. When you make extended comparisons, organize them so they are easy to follow. Cover the same aspects of all things compared. If you compare two works and talk about metaphor, symbolism, and imagery in one work, you need to talk about these things in the same order in the other work. Also, discuss the aspects in the same order for each thing compared. If you talk about metaphor, symbolism, and imagery in one work, keep the same order when you discuss the other work: metaphor first, symbolism second, imagery last. The outline for such a comparison would look like this: Work #1 Metaphor Symbolism Imagery Work #2 Metaphor Symbolism Imagery For comparisons of more than two things or for long, complex comparisons, another method of organization may be easier for readers to follow: Metaphor Work #1 Work #2 Work #3 Symbolism Work #1 Work #2 Work #3 Imagery Work #1 Work #2 Work #3 Notice how the student essay of the Odyssey uses the second plan of comparison: Claim: Eden and Ogygia are similar. Reason #1: Their physical features are similar. A. Eden has certain physical features (described). B. Ogygia’s physical features (described) are almost exactly the same. Reason #2: Their inhabitants live comfortable and painfree lives. A. Eden B. Ogygia Reason #3 Their inhabitants have companionship. A. Eden B. Ogygia Reasons #4: Both places are free from death. A. Eden B. Ogygia There are other ways to organize comparisons. You could, for example, discuss all the similarities in one place and all the differences in another. But the general rule is to make the comparison thorough and orderly, so the reader can see all the lines of similarity and difference.