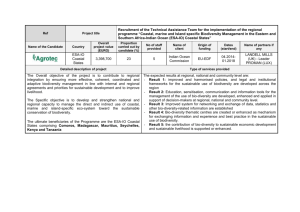

section ii: strategic results framework and gef increment

advertisement