Research Study on International Recycling Experience

Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs

Research Study on

International Recycling Experience

Annex A

A8 SEATTLE

A8.1 OVERVIEW

A summary description of Seattle and key recycling data are presented in Table A8.1.

Table A8.8.1 Overview of Seattle

City

Background

Population

Density

Details

534 700

1 045/km2

Type of area Urban

Type of housing Apartments (1-4 units): 60%

Apartments (5 units or more): 40%

Definition of

MSW

Residential, commercial and industrial non hazardous waste & small-scale construction and demolition waste

Recycling target 60% by 2008. The recycling goals have been set by sector as follows:

Single family (1-4 units per building: 70%;

Multifamily (5 or more): 37%;

Commercial: 65%;

Self Haul: 39%.

Recycling achievement

Principal

Recycling Drivers

37% of waste collected by municipality (1998)

cost of landfill is more expensive (there is no incineration); markets for end products; wide coverage of kerbside collection;

volume based charges; public information activities.

Seattle is an urban community with major industries including computer software and hardware, aircraft manufacturing, financial management, insurance, real estate and tourism. Recycling rates in other parts of the State are comparable to that of Seattle.

The city’s two landfills closed in 1983 and 1986. The cost of using the county landfill was triple the amount of using

Seattle’s closed landfills. Citizen opposition was overwhelmingly against the development of a waste-toenergy options. The City had to consider alternative waste management options other than disposal. Up until this point,

25 per cent of the commercial sector’s solid waste was being recycled at nearly 50 transfer stations and buy back stations throughout the city. Seattle's kerbside recycling programme started in 1988, in response to overwhelming public pressure to recycle.

The recycling achievement figure of 37 per cent refers to waste managed by the municipality. If we include private sector recycling programmes of MSW, this rate increases to

44 per cent in 1998.

A8.2 RECYCLING TRENDS

In 1998, the municipality managed 47 per cent of the waste generated in the city. Of this material, the City recycled 37 per cent, originating from the domestic sector under four services: kerbside recycling, apartment recycling, kerbside garden waste collection and refuse collection. Of the remaining 53 per cent of waste, there is little data available on how much originates from the commercial sector and how much from the domestic sector. 50 per cent was recycled.

Combined, the City and private operators recycled 43.6 per cent of the waste stream.

Figure A8.1 Recycling trends in Seattle for household waste (1998)

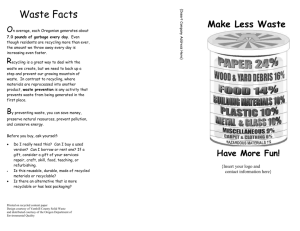

Over two thirds of all recycling in the kerbside collection scheme is accounted for by paper and newsprint. Around 20 per cent is glass.

The City has adopted a 2008 goal of recycling 60 per cent of

MSW broken down by the following programme categories:

Table A8.8.2 Development of future municipality recycling programmes in Seattle

City recycling programmes

Kerbside recycling

Kerbside garden waste collection

Apartment collection

Self haul garden waste

Collection at civic amenity sites

Garden waste composting 9

Residential kitchen waste composting 0

Percentage of total recycling

1998 2008

42 33

29

7

9

3.5

17

13

5

14

11

6

Kerbside collection in 1998 accounted for 71 per cent of household waste collection. In the future, emphasis will be placed on developing collection at civic amenity sites, expansion of the apartment recycling programme and developing a programme of kitchen waste composting.

Additional recycling from the other recyclers is expected to help the City reach 60 per cent recycling by the year 2008.

A8.3 MSW MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE

Local authorities are responsible for all levels of solid waste management. The City contracts out waste management services for the domestic and commercial sectors. Recyclable materials from the domestic sector are delivered to private processing facilities operated by the two contractors providing the separate collection service. One company services the areas north of the shipping canal and another the areas south of the canal. These two companies are the same that were originally contracted when separate collection began in 1988.

Waste from the domestic sector is taken to two city owned and operated civic amenity sites and then taken by rail to a private landfill in eastern Oregon under a long term contract through to 2028. Garden waste is processed at a privately owned and operated composting facility.

For commercial waste, the two collection companies are paid directly by the private businesses that contract with them for the refuse and recycling service. Commercial waste is taken to two privately owned transfer Stations. Private recycling companies also compete to provide collection of recyclables from the city's businesses. These companies take the recyclables to their own processing facilities.

A8.4 COLLECTION MECHANISMS AND

ACCESSIBILITY

The kerbside collection service is provided to all residents in buildings with four or less units per building. A separate

Apartment Recycling programme is provided for multifamily apartment complexes with five or more units per building. 58 per cent of these households have collection services provided by the City, organised through the building owner. 69 per cent have ‘signed up’ for separate collection. It is the building owner’s choice on how recycling facilities are organised, although there is not much incentive to increase recycling rates as waste costs are passed through to the residents. The apartment complexes not covered by municipal collection services have access to the two civic amenity sites. In a few cases a private recycler provides collection services.

Until April 1, 2000 the residential kerbside collection system north of the shipping canal provided weekly collection

services and residents separated their recyclables into three stackable bins. In the area south of the canal, collection was monthly and residents put all recyclables (except glass) in a

96 gallon cart.

From April 1, 2000 the City has updated its contracts for waste collection with the same companies and has instituted some changes to standard practice. Refuse is collected every week while recycling and garden waste are now collected on alternate weeks throughout the city. All recyclables (except glass) are commingled and recycling ‘carts’ (‘wheelie’ bins) are used. 64 and 96 gallon ‘wheelie’ bins are distributed free to each household. The bins are tipped into recycling vehicles using automated bin tippers. Glass is placed in a separate bin.

Box A8.1 Advantages of using ‘carts’ for separate collection of recyclables

The municipality has chosen to use ‘wheelie’ bins in order to provide sufficient capacity to each resident for as much recyclable material as they can generate.

The municipality believes that the ‘wheelie’ bins hold more material, making alternate week recycling service more acceptable.

‘Wheelie’ bins help contain the materials, keep out rain and pests and reduce litter.

‘Wheelie’ bins are believed to be easier to handle for most residents and allow the resident to get all their recyclables to the kerb in one trip. ‘Wheelie’ bins are moved to the kerb for elderly and disabled people.

Combining the materials has helped the City's contractors save money and provide lower cost services to the City. The projected savings from the use of ‘wheelie’ bins is over

$2 million each year. Use of ‘wheelie’ bins and bin tippers has been shown to significantly reduce worker injuries.

Additional ‘wheelie’ bins are available free of charge. The bins can be replaced free of charge every three years.

Processing of this single stream of recyclables is more

yet results in lower costs for collection of the

recyclables at the kerb and facilitates participation. Most garden waste collected is collected at the kerb, under a separate kerbside collection programme.

A8.4.1 Participation Rate

The municipality have not carried out studies on participation rates to date.

A8.5 COSTS AND REVENUES

In Seattle it costs less to recycle than to landfill solid waste.

In the years between 1988 and 1995, Seattle residents saved

over $12 million (£7.6 million) [2]

composting instead of landfilling.

Recycling costs consist of a base price per ton

minus a variable amount per ton based on market prices). The municipality bears all the risk associated with a decrease in market prices for recycled materials. A base price is identified for each material. If the price falls below this base price, the City pays the difference. Similarly, if the price increases beyond the base price, the City deducts the difference from what it pays for collection services. The base prices are given in Table A8.3.

Table A8.8.3 Minimum price levels for recycled materials

Material

Tin cans

Glass

Base price (£/ton)

4.76

Brown: 15.58;

Clear: 18.62;

Green: £0

Newspaper

Mixed waste paper

Aluminium cans

Plastics (PET & HDPE)

24.49

6.49

£672

£16

On average in 1995, households paid about $20 (£13) per month for solid waste services (including collection of garden waste). Of this, recycling services accounted for $3.20 (£2) per household.

The total cost of the kerbside collection programme is $5.4 million (£3.4 million) in 1999, equivalent to $86.39 (£55) per ton collected by the kerbside. This cost reflects the cost of collection and sorting, and the cost of disposal of residues, net of any revenue received for sale of the material. These figures do not include cost of bin replacement or Seattle

Public Utilities administration and education costs. 60 per cent of the City’s population are covered by kerbside collection, which amounts to 149 500 households. Dividing the total cost figure for kerbside recycling by the number of people it applies to gives a cost per household per year of around $36 (£23) (1999 data).

Revenues are around $38.40 (£24) per household per year, which, over 149 500 households, gives a total revenue of around $5.7 million (£3.6 million) (1995 data). Depending on the prices of recycled materials, the municipality may make a surplus, which is held in reserve when market prices are low.

A8.6 SUCCESS OF THE SCHEME

The coverage of kerbside collection is wide, although it covers a larger percentage of low density apartment blocks.

Responsibility for recycling for high density blocks falls on building owners, and the incentives to recycle are therefore weakened.

Volume-based waste charges provide a further incentive for households to reduce their refuse. For high density apartment blocks the charges fall on building owners, and the incentive to reduce waste is, again, weaker. Costs are simply passed through to the residents of the apartment block.

There seem to a varied set of markets for most of the recycled materials.

Public information activities are essential in order for households to participate in recycling in the most effective way.

A8.7 LEGAL AND REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS

Currently, the only legal requirement that might encourage recycling is a City ban of garden waste from the waste stream.

Households must either sign up for garden waste collection services or implement home garden waste reduction and composting practices.

Seattle Public Utilities proposes to introduce bans or mandates if sector goals are not met. Multi-family housing will be tracked closely with a two year window (end of year

2000) to reach an 80 per cent apartment sign-up goal for increased participation (the 1998 rate was 60 per cent of eligible apartments). Failure to reach those goals will result in a requirement placed on building owners to sign up for the recycling program. Bans on the disposal of targeted recyclable materials (for example, clean paper) are also possible.

A8.8 FISCAL INCENTIVES

A8.8.1 Charging Systems for Waste Management

Prior to 1988, the domestic sector paid flat fees for waste services. In 1988, a volume-based fee was introduced. A resident can choose the level of refuse collection service which determines the size of the charge. Waste containers are provided free. Households living in low density apartments are charged directly. Data are kept on which bin sizes belong to which households. The system is reported to work well. In the case of high density apartments, building owners are charged, who pass the cost on to the residents of the building.

The incentive to reduce waste is weakened.

Since 1988, there has been a significant overall reduction in the average bin size that single family residents are signing up for. The size of bins, the level of charge and their distribution is as follows:

Table 8.4 Variable charge system for household refuse collection

Size of bin

Annual charge (£)

Distribution (% of households)

12 gallon 76 4

19 gallon 94

30 gallon 122

60 gallon 245

26

62

8

Additional 30 gallon bins provided at a charge of $16.10 (£10) a month.

Residents pay for garden waste collection with a separate fee.

Seattle Public Utilities charges each resident every other month in a combined utility bill (water, sewer, electricity and domestic waste). Seattle residents are required to subscribe to the waste collection service. The charge rates cover the cost of collecting and disposing of refuse and the cost of the recycling service. The provision of recycling services and the shift by households to less waste disposal have contained residential waste management costs for the City. Minor charge increases have been made in 1989, 1992 and 1994, driven by addition of new programmes (for example, a household hazardous waste service and litter cleanup) and the full incorporation of the landfill cleanup costs for the landfills used by the City prior to the mid-1980s. However, the average single-family resident's bill is lower now than it was in 1988.

A8.9 PUBLIC AWARENESS

The ‘Community Partnership’ programme focuses on general city issues such as litter and schools and adult education. The following types of outreach approaches are used to encourage recycling:

Information including brochures, the ‘Kerb Waste

Times’, newsletters, pamphlets, adverts in newspapers

and on radio;

Feedback mechanisms including surveys and focus groups;

Education through school curricula and community workshops offering resources for learning better

waste management behavior;

Volunteers through ‘friends of recycling’ and other citizen groups that support programme goals;

Neighbourhood projects through grants and technical assistance, bringing in more tailored and focused communication tools and assistance to individual neighbourhoods.

As part of the new Plan Update, special attention will be paid to:

engaging youth as neighborhood stewards;

providing resources to help people take local action; expand outreach through volunteers;

improve services to under-served communities, and

emphasize the message of conservation and stewardship.

A8.10 MARKETS FOR END PRODUCTS

The City has well-established markets for its stream of recycled materials. The contractors are responsible for processing the material to end-market specifications. Each has contractual arrangements with a variety of end-markets to ensure the long term viability of the recycling system. These end-markets rely on programmes like Seattle's as an important source of industrial feedstock. The following table summarises the end markets for the materials recycled:

Table A8.8.5 End markets for products

Material End use

Cardboard Cardboard boxes

Mixed paper Newspaper, paper products (writing paper, tissue, chipboard used for cereal boxes)

Green, brown Glass bottles (99%). A small amount to sandblasting and clear glass industry.

Aluminium cans and other aluminium products Aluminium cans

Tin cans Steel products

Plastics Blow moulded non-food packaging fibre for garments

(i.e. fleeces) and stuffed toys; carpet fibres, clothing fibres, containers, plastic lumber, toy parts and liners for slippers and shoes, engineered wood products.

Corrugated medium Polycoated paper

Aseptic packaging

Corrugated medium

A8.11 FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS

The municipality is considering the following to improve recycling services:

adding a separate collection for composting of kitchen waste and compostable paper if projected benefits outweigh the project costs; increased efforts to develop markets for recycled materials by promoting public-private partnerships;

education campaigns to increase recycling, with the objective increase paper and cardboard recycling from the residential sector and paper, plastic film and wood

[1] Processing facilities separate this single stream of recyclables using a combination of mechanical and manual approaches. Screening devices are used to separate lightweight and rollable containers from heavier flat paper products. Light plastic containers are removed from the stream using air suction systems. Magnetic separation systems pull out metal and tin cans. Eddy current magnetic separation systems pull out aluminum cans. Paper is sorted manually.

[2] FT 19/04/00 $0.634 = £1

[3] 1 metric tonne = 0.98405 Imperial tons

[ Previous ] [ Contents ] [ Next ]

Published 26 April 2001

Waste Index

Environmental Protection Index

Defra Home Page