Paper - ILPC

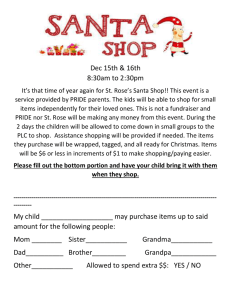

advertisement

The 28th International Labour Process Conference, Rutgers University, New Jersey, March 15-17 2010 Lone riders for collective interests Union leadership as maneuvering between company goals and worker wants By Hanne O. Finnestrand1 & Johan E. Ravn1 ”While wage issues are settled through a couple of meetings during Spring, the rest of the union leader’s year consists of working with strategic processes around the development of a safe and interesting enterprise. For me as union leader, this is the crucial work condition” (Conversation with chief union leader) 1 Introduction Ever since Marx, and particularly since the heydays of the neo-Marxist labor process theory of the seventies, capital’s interests have been seen as twofold: to maximize profits, of course, but also to maintain control of the so-called labor process. Taking this seriously, organized work’s counter-interest is to maximize their share of the profits, but also to develop opposition to a tightening management control of the labor process. A common union strategy is to focus on the first: to use bargaining power to increase wages, decrease workload, and stop dismissals. To the degree that labor has offered opposition to tightening management control, it has very often taken a very reactive mode. 1 SINTEF Technology and society, Department of Industrial management. hanne.o.finnestrand@sintef.no ; johan.ravn@sintef.no 1 We do not contest the legitimacy of this, but we do ask whether this is the best a union can do. We argue that the latter interest sometimes can be served better by the union leaders taking responsibility for and involving in corporate strategy, enterprise development, and worker participation. This is a strategy different from the purely antagonist. It is in other words not the presence or no-presence of the union that determines the degree of productivity or innovation in the enterprise, but rather how the unions carry out their basic mission, namely to attend to and safeguard the conditions of their members. 2 The union leader – between worker wants and company goals Social dialogue refers to interaction between the social partners of the work place intended to influence the arrangement and development of work related issues. Such a social dialogue can be more or less cooperative in its character. In 2004, Huzzard, Gregory and Scott proposed the concepts of “boxing” and “dancing” to denote adversarial and co-operative modes of industrial relations, respectively. Although ‘boxing’ may denote the most common perception of what the game of industrial relations is about, we also find dancing. Also one should not necessarily conceive of “boxing” and ”dancing” as practices mutually excluding one another. One and the same industrial relation may be adversarial and co-operative simultaneously. Some managers and union leaders cope well with practicing double roles and being each others’ partners and opponents concurrently. Many enterprises, managers and union representatives have developed the ability to cooperate in highly sophisticated ways on issues normally dealt with by top management alone (Kochan and Osterman 1994). The Industrial Democracy projects of the 1960s probably constitutes the most vital and influential contribution to the field of participative enterprise development in Norway. Emery and Thorsrud (1976) developed a research program on democratisation of work in practice supported by “The Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions” (LO) and “Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise” (NHO). The most important item of the program was formulated as “a study of the roots of industrial 2 democracy under the condition of personal participation in the workplace” (Emery and Thorsrud 1976:10). The researchers carried out sequential field experiments in which alternative forms of work organization were developed and tested. The effects on the participation of employees were examined at different levels within the organization (Eijnatten 1993). Emery and Thorsrud designed, took part in and accounted a project principally collaboration and value creation through co-operation between the employees on the shop floor and the management. The results of the The Industrial Democracy project quickly found their way into a new work environment Act (1977) and into the basic agreement between the principal social partners, legitimating collaborative union-management relationships in both camps. The knowledge gained through the Industrial Democracy program and many others within the same field2 have given important contributions to enterprise development through broad participation with the employees and the trade union as vital partners. Kochan and Osterman (1994) use the term mutual gains3 enterprise in order to elaborate fruitful cooperation between the union and the management. They claim that in order to achieve and sustain competitive advantages from the human resources in the enterprise, the parties must acknowledge and support each others interests. The employees must commit their energies to meeting the economic objectives of the managers. The managers – and the owners for that matter - must on the other hand share the economic returns with employees and invest those returns in ways that promote the long-run economic security of the work force. And most important; everybody involved in decision making must behave in ways that build and maintain the trust of the work force. The argument is clear – also from the union’s perspective; an enterprise that is both competitive and worker friendly is an enterprise worth fighting for. Or said in a mutual gains perspective: A competitive and worker friendly enterprise is worth collaborating for. 2 See Deutsch, S. (2005). A Researcher's Guide to Worker Participation, Labor and Economic and Industrial Democracy. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 26, 645-656., Gill, C. (2009). Union impact on the effective adoption of High Performance Work Practices. Human Resource Management Review, 19, 39-50., and Toulmin, S., & Gustavsen, B. (1996). Beyond theory : changing organizations through participation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publ. Co. for overviews and examples. 3 First introduced by: Cohen Cohen-Rosenthal, E., & Burton, C. E. (1987). Mutual Gains - A Guide to Union-Management Cooperation. New York: Praeger Publishers. 3 Kochan and Osterman argue however that the unions in most cases haven’t been able to champion the new ways of empowering and representing workers, so in many settings unions simply became marginalized and at least served as junior partners in managing the change process (Kochan and Osterman 1994). Union leaders are as much as other leaders dependent on developing their competencies and be offered a position where they have the ability and freedom to grow with competence and experience. If the leadership the union leaders exercise in development processes on the shop floor is not accepted by the management, the union leaders will soon loose their credibility as dancing partners. This is however a neglected point in the participative democracy literature. It is interesting that Thorsrud and Emery, who emphasized the importance of the workers arbitrariness and authority in the Industrial Democracy project, did not stress leadership as a separate discipline among the workers or the union per se. The problem in the case of Thorsrud and Emery was that they didn’t want to talk about leadership at all. They chose words like participation and cooperation (Byrkjeflot 2002). To deal with trade unions as collective entities mirrors in many ways the nature of trade union, but it is our intention to reflect upon the position of the union leader as a unique position especially regarding the members benefits. Unions may be represented in the company boards, taking part in the board’s discussion and decision making about company direction. In other cases, the CEO may discuss strategic issues with the union leader. In order to improve the general conditions of the members, union leaders find it important to go into discourse with company management about company development. They work to develop company quality and innovativity not because this brings profit to the owners, but because it serves the interests of the employees. Acquiring hands-on business knowledge serves as a means to discursive power to the union leaders. When they know more about the overall business process they have a stronger base to negotiate from. Union representatives such as these operate on arenas and play roles very different from the life world of those who elected them. Their praxis differs from that of their 4 members. They make other experiences and develop competencies and perspectives likely to differ from those of their members. This also influences the relationship between the union representative and the management. When a long-term relationship emerges between the parties, repeated exchanges create a system of diffuse social norms of mutual obligation and expectations of equitable treatment (Malinowski 1922; Zucker 1986). Research also indicate that repeated positive interactions between different parties contribute to helpful attitude that in turn create trust (Mayer et al. 1995) and that positive interactions over time form an accumulating foundation that allows both parties to have increasing confidence in each other’s actions (Murnighan et al. 2004). By working together with management on organization development issues, it is likely that the union representative gains management’s trust and the other way round. For the union leader such relationship may be very complicated to deal with. In the classic work Workers’ Collective4, Lysgaard (1961) demonstrated how the Worker Collective creates rules for communication and cooperation within their own group and with others outside the group. Some of the characteristics of the Workers’ Collective are the employees’ attempts of setting the production standards in relating to pace, and how to mark the differences between “we” and “them”. “Them” could be the foremen, the managers, or the salaried groups. The point is however that these groups where associated as the enterprise, and therefore represented a system based on profit and techno-economic efficiency. Lysgaard does also describe how the workers are noticing when a colleague crosses the border to “the other side” – for example from being a worker to being a foreman. In the Worker Collective, Lysgaard sets the techno-economic system up against the human factors, and shows us how the Worker Collective is a way of handling the diversity or the incongruity of the systems’ demands. The Workers’ Collective acts on behalf of the individual worker in the sense that the Workers’ Collective work as a bumper or moderator towards the techno-economic demands. 4 The study of the Workers Collective was unfortunately never translated into English, but the study had and still has a great impact within social research in general and especially organization studies in the Scandinavian countries. 5 A union leader who starts cooperating with the management on arenas associated with the techno-economic system is forced out of the Worker Collective. Not is he only working on developing a more efficiency enterprise, he is also physically separated from the workers on the shop floor. The days are spent on arenas invisible for the members and the union leader may experience that the members see him as increasingly alienated from them. And even when he is back on the familiar ground with his members, the conditions for dialogue may have deteriorated. There are particularly two reasons for this; Confidentiality issues and a lack of a shared set of models and language. A union representative who meets with the CEO or sits at the board is likely to have to handle confidential corporate information that he cannot share freely with the members. He may be aware of plans about downsizing or outsourcing without being allowed to tell. This hinders him from approaching his peers freely, and eventually, it also may hinder them from fully trusting him. A lack of a shared set of models and language also enters the picture after a while. This is what Bråten (1973) termed model monopoly: conceptual power asymmetry in communication creates a situation of so-called model monopoly: All issues debated get framed and are given names by some, forcing strong conceptual constraints on the communicative participation of the others. When the union leader is to report back to his members, he has to report back in the language and by help of the models as they were used by management and board. Both the holding back due to confidentiality and the reframing or “newspeak” due to managements’ model monopoly are likely to develop a perceived split between the perspective of the leader and those of the members. This perceived changed perspective may be understood as a loss of loyalty to the original cause. Union leaders risk alienation in that their members do not understand what they say or do, or why. This alienation may be due to the fact that the members don’t have the capacity to understand the choices made my their union leader or that the union representative have to make difficult choices that he think is the best for the members although it might not appear so for the members. 6 Rubinstein (2001) proposes that employees trust unions because they are independent and union leaders, unlike managers, are elected to represent the interests of employees. This trust is however exposed when the union representative behave or doesn’t act in accordance to the members’ expectation. Having taken on tasks in the company boardroom and other important arenas, the union representatives have had other roles and made other experiences than their members. The dilemma the union representative encounter is that he may have to simultaneously meet the expectations of one party and violate the expectations of another. In trying to manage the perception of diverse constituencies the union representative may represent him selves in inconsistent ways. When somebody faces such dilemmas they are forced to take an action that sustains the trust of one party but breaks the trust of another (Dirks and Skarlicki 2004). For the members on the shop floor, unexpected or incomprehensible behavior by the union may be interpreted as the union representative being dishonest or not being trustworthy. Research indicates that individuals often emphasize a leader’s disposition and not to the dilemma the leader faces (Gilbert and Malone 1995). It is likely that the union representative with its responsibilities experiences the same treatment. The questions we would like to elaborate on in this paper are: In what way are the union leaders serving the member interests through his acquired corporate competence and how does he get the members to acknowledge his involvement in the corporate territory? 7 3 Model The figure below illustrates the union leader’s movement into what we have called the “management territory”. Figure 1: The union leader’s position as protector through corporate competence Instead of operating within the union community and use bargaining power to increase wages, decrease workload, and stop dismissals, the union leader may choose to situate himself within the “management territory” developing corporate competence in order to make sure that the members are being represented in the best possible ways. For the union leader this leads to new knowledge and possibilities like developing a close relationship to the management, getting to know confidential matters, and developing understanding for the corporate world noticeable through different set of language or models. This change of arena leads to changes or challenges in relation to the members. The union leaders are much less present in the production, he may seem alienated from the members with a new set of terminologies and perspectives. Perspectives that may seem strange and incomprehensible by the members he represents. 8 4 Method and data The primary data for this research stems from a research project studying and developing the roles of managers and union leaders in four companies from a range of industries in Norway in the period 2006-2008. In this project it was our primary purpose to produce practical knowledge that is useful for the participants in their work situation by bringing together action and reflection, theory and practice in participation with others (Reason and Bradbury 2008). During this time we have facilitated discussions both within and across the management- and union groups, followed the participants’ projects in their company, staged different group work, and observed the union leaders in action. We have in addition carried out interviews and discussions with union representatives, managers, and employees from both the participating companies and other manufacturing companies the year after in order to be able to go deeper into the material and to discuss some of our findings. The principal methodology for this research is a blend of ethnographic studies (Stake 2005; Yin 1989), case studies (Stake 2005; Yin 1989), qualitative semi-structured interviewing (Creswell 2007)l, shadowing (Czarniawska 2007) and various types of action research intervention/co-reflection (Elden and Levin 1991). Three of the cases also carry valuable longitudinal background data derived from many sources over a period of up to ten years. The two last ones were designed to follow up on findings from the three other more longitudinal cases Our relationship to the companies that participated in the research project has developed into a relationship based on trust, respect, and mutual gains. We still operate as some kind of friendly outsiders (Greenwood and Levin 2007) who are taking part of the discussion between the managers and the union representatives. It is therefore complicated to be specific on what kind of data we base our findings, although the table below is an attempt in that matter. 9 Company Data Ferrosilicon Participated in the research project 2006-2008. Additional interviews with union leaders, workers, managers and technical staff early 2009 Power Various interactions with the company since 1998. Participated in the Electronic research project 2006-2008. Additional discussion with three union representatives, June 2009. Participation in a one day seminar with 19 union representatives December 2009 Future Based on interview with top union leader, March 2009 Furniture Steeldrill Various interactions with the company since 1998. Participated in the research project 2006-2008. Additional interview with the top union leader, open observation of the interaction and discussions between union leader and members, in addition to participating in 10 team meetings on the shop floor and 3 production meetings. Cylindertech Based on interviews and shadowing (Czarniawska 2007) during two days of the top union leader, October 2009 5 Case Ferrosilicon The history of Ferrosilicon of the process industry goes back to 1904, when a forerunner to the present day operation was founded. The present plant with its first smelting furnace for the production of ferrosilicon opened in 1964. Metallurgical grade silicon is the main product at Ferrosilicon is used as raw material in the production of silicones and as an alloying element to aluminium. Besides silicon, the filtration of the exhaust gases from the smelting furnaces gives microsilica, their other main product. Ferrosilicon produces niche metal for a highly competitive global market, facing severe competition. The competitive advantage has developed into emphasis on continuous improvements of their socio-technical organization of work, as well as large investments into technology aimed at exploiting the metal production into bi-products for the niche market. 10 The same thing happened to ferrosilicon as to almost any other industrial product as the global collapse unfolded in 2008. By 2009 Ferrosilicon’s markets had almost disappeared. Early in the year, they had to close down the first of their two melting furnaces, and by June, the whole plant was closed down. Still, they managed without sending out notices of dismissal. They shortened the work week, the workers took pay-cuts, and the regular labour force was put in charge of a thorough maintenance program for the furnaces and the whole production site. Eventually they had to effectuate lay-offs. The whole program was developed through collaboration between management and the metal workers’ union. Such actions are never popular with the members, but acceptable if the alternative is seen as worse, which it was by the majority of the workers. But some union members saw it differently. These came from the units furthest away from core business, e.g. the Loading/unloading team. An initiative came up to fire the senior union leader. Power Electronic Power Electronic was established 100 years ago. Through the decades it has undergone a lot of changes. Several product areas have been outsourced. A couple of years ago the main remaining units were doing electrical installation work as well as design, engineering and production of power supply systems serving global markets. The company has a history of collaborative industrial relations. The electrical heater production lines of the company, once a central part, participated in the Norwegian Industrial Democracy Project (Emery and Thorsrud 1976). The original scientific management design of the shop-floor was then abandoned in favour of introducing semi-autonomous work groups. The first groups were launched in 1972, and there are still semi-autonomous work groups in place, as the sole survivors from the time of the Norwegian Industrial Democracy Project. A couple of years ago Power Electronic Installation was facing downturns in their markets. The perception was that one of their local offices did not have sufficient demand for their services. Management saw no alternative to effectuate (temporary) lay-offs. According to Norwegian worklife regulation, employees should get formally notified two weeks ahead if they are to be laid off. Management was ready 11 to send out the lay-off notices, but then the union intervened. According to their assessment, the market situation was about to improve soon, and if they were right, there would be no need for (temporary) lay-offs. They went to management and made an offer: instead of insisting on their members’ right to lay-off notice two weeks ahead, they proposed to shorten the notice time to only three days. Thus management could postpone the lay-off notices a week and half, without delaying the eventual execution of the lay-off. The union’s intervention turned out to be a lucky one. Within days, new orders came in to this local office. The volume of these new contracts was sufficient to remove the need for lay-offs. Steeldrill Steeldrill is a mechanical company producing equipments for other manufacturing companies. The numbers of employees have grown over the years and today they are approximately 100 employees. 2/3 of the employees are working on the shop floor while 1/3 of the employees are working with product development or sale and marketing. In 2007 they had difficulties hiring people as fast as the marked demanded. Their products were quite popular and the order reserve was huge. They claimed they had “vacuumed” the marked for qualified workers and other manufacturing companies in the area started to give them nicknames like “cannibal in the industrial community” since they were willing to “eat” from other companies’ workforce and outbid the market’s wages. The workers on the shop floor - who had an updated version of the order reserve on their computer screen - started to feel the pressure as the orders changed colors from black to red. They were not able to deliver before deadline although most of them worked overtime and weekends. The workers were not satisfied with the situation and this dissatisfaction started to spread throughout the shop floor before it hit the union leader: Union leader: “It is important that we involve. We cannot be in a situation where we stop caring. I’m not saying that that’s the case. But if somebody feels that this is difficult and that they don’t want to do this, it’s OK, but you have to prioritize. Maybe it’s a choice between plague and cholera, but you have to make a choice”. 12 First worker on the shop floor: “We have stepped on the gas for over two years now. If we think car, I’m afraid the car will beak down soon. I think there are signs of that. I’m not sure if I have the energy to carry on like this much longer. It is at least important that we see the light at the end of the tunnel”. Second worker on the shop floor: “It is only us who work with the machines who have to contribute. We had to give up N.N. [a machine worker] for the engineers. (…)I have not seen the summery over overtime work, but I’m sure we work much more than them [the engineers]. We need them to do their work in order to be able to do ours” Union leader: “It’s OK that you think so. But it shouldn’t be “we” and “them”. They [the engineers] are doing a good job. N.N. is needed badly also among them. You are not wrong, but I wanted to give an explanation”. The union leader reported that he often found himself in a position of defending the management’s decisions. Since he was present at most of the production meetings with the managers he understood their arguments and priorities, but he was clearly aware of the workers’ difficult situation. He was sure that the tight situation would improve as long as the workers on the shop floor, the engineers, and the management could communicate about their difficulties and frustration and seek solutions together. The union leader saw himself as some kind of a conflict negotiator or mediator between the parties in the company, but ended in some kind of a hostage situation. The managers found it annoying that the union leader demanded to be invited into all arenas and members felt that the union leader had alienated him selves from them. He was eventually sacked as the union leader. Future Furniture Future Furniture produces furniture for the international market. In 2008 they were hit by the same finance crises as most other industry. The management realized that they had to give some of the workforce the notice and the union representatives followed their argument; it was better that 100 employees were without work for a 13 while than a situation where the entire company with its 800 employees would fail on a longer run. For the union representative the entire process of cooperating with the management in such a difficult area lead to many complicated situations – not least in relation to how they handled the information they received in discussions with the management. The workers wanted to know whether they were in danger of loosing their job or being laid off. Some rumors had it that the company would follow certain models that would have negative effects on the senior employees. Others had it that the latest employees would have to leave the company. Some rumors had it that one of the factory sites would be shut down, while others had it that the management would keep all the sites in the process. The union leader was quite frustrated by all the misinformation that spread like wildfire and suspected that some of the workers made up things and spread it because they found it amusing. He claimed that he informed the members as much as possible, but the members were asking for more. Most of the relevant information during the process of workforce reduction was in addition confidential. Future Furniture is quoted on the stock exchange and it is therefore particularly important that the persons involved in strategic decisions know how to handle vital information. The union leader was loyal to this regulation. Some of the biggest news agencies called him frequently since he was voted into the position. The union leader thought the media saw him as a direct line into the companies’ heart. He was discreet and didn’t leak any information to anybody – especially not to any of the employees. He suspected however that the company’s managers weren’t as strict on this area as him since he often was confronted with rumors among the employees – rumors that were almost the truth but not entirely. Cylindertech Cylindertech is a quite young company with a little less than 100 employees. They produce mainly for the private market all over the world. In addition they have tried to establish a position within the car industry with a new and innovative product. This last marked area has not been as profitable as wished or needed, and the difficult 14 financial position during 2008-2009 demanded some kind of action by the board. The sickness absence touched 30 % after the CEO made known that the car section of the company would be shut down within the year. People were worried they would loose their job, and this anxiety diverge all over the companies’ sections – included those parts that were doing fine. The management didn’t however grasp or take in this anxiety and the high number of absence in the company didn’t lead to any changes in work procedures such as how the employees were informed. The managers had some years earlier installed an information booth in the middle of the production premises with a huge computer screen and a keyboard for employees to register unwanted incidents, dead halts, order backlogs, different requirements in order to do the job, and so on. The management were quite satisfied with this arrangement and claimed that it was a good solution to both their own and the employees’ demands for information. The union leader was not satisfied with the situation. He claimed that as many as 40 % of the employees on the shop floor had dyslexia or other writing disabilities and that those of the workers who struggled with writing would avoid using this information booth as the managers intended. As the union leader commented: Almost half of the work force is kept from participation as long as the tool for participation is based on the managers’ way of communicating; namely through writing. The union leader had his own problems regarding communicating with the members. Since he was a union leader in a rather small company, only 14 % of his time at work was dedicated union tasks. The rest of the time he was supposed to work as a mechanic together with his work team. These 14 % were merely a wishful thought and had nothing to do with the real situation. The union leader was quite young and he wanted to develop into a knowledgeable and competent union leader – someone the members could trust and turn to. The desire of being a proactive and competent union leader did however put the union leader in a catch 22 position. In order to develop into a good union leader he needed to spend time on most of the arenas where he was able to make a difference. This did however affect the mechanic team where we worked because he was often away and left them with all the work. The 15 colleagues were dissatisfaction with the situation. The more effort the union leader put into being a good representative, the more the dissatisfaction grew among the members. The union leader there tried however to meet the members by walking an extra round in the production premises when possible. Ha had in addition developed a social medium equivalent to “Facebook” where the members were able to propose suggestions, discuss different subjects, and give and receive messages. 6 Discussion & conclusion As most keen observers will have seen for themselves, it is not difficult to find workplaces, past and present, where the industrial relations are quite hostile and very little beyond negotiation and conflict resolution is taking place. Huzzard et.al (2004) expanded the perspective on unionism when describing the dualism of boxing and dancing. Employees may contribute to industrial growth and moderate wage increase, and in return secure working conditions and benefit from growth. Sometimes dancing is a better way forward than boxing. One key result from the Industrial Democracy Project in the sixties is the Norwegian Work Environment Act of 1977. Compared to similar acts in other (European) countries the legal claim for employee collaboration on issues related to organization of work is rather unique. For instance, employees are entitled to be involved in restructuring processes at the work place, including that of implementing new technology. A lot of the democratic involvement that the employees are entitled to takes place in a representative manner, and this is where the union leader enters the picture. The quote opening this paper comes from such a position. Some of these union leaders have been in office for quite a while. Although they have not forgotten what is their role and duty, some of them – like the one in the quote - have developed a whole new set of vision/strategy and methodology in order to serve the interests of their members. Sometimes they are boxing, but it looks like dancing, also to their members. They may be successful in securing rights, reducing hazards, increasing pay etc, but they may “look too co-operative”. The practice of such a union leader comes with a risk of being seen as deserting from the colors of the rank and file. The cases show that this may be the case, and that the there are differences as to how well the union leaders manage to cope with this. 16 6.1 Union leaders serving the member interests through corporate competence The case with Power Electronic demonstrates union representatives who understood the business situation of the company sufficiently well to propose a way forward that was not informed by a “maximize protection” doctrine, instead the union leaders used their business knowledge to make a more risky and rather creative move. The case also shows a management – union relationship marked not just by power strategies, bargaining and negotiation, but also by trust and cooperation. The corporate competence on which the union representatives acted was additionally developed through management – union interaction. Setting aside their members’ right to lay-off notice two weeks ahead is – seen isolated – an infringement of their rights, and a highly atypical union strategy. Union members who were willing to accept such an initiative from their representatives demonstrate trust in their leaders. One shouldn’t however think that a way of coping like this could happen anywhere. This company has had a long tradition for interaction between management and the blue collar unions. It made its first experiments with semi-autonomous work groups by the end of the sixties. It is reasonable to assume that this lengthy experience with cooperation has developed reasonably high levels of trust, in the company as a whole and within the shop union in particular. As in the case of Power Electronic, the union leaders in Ferrosilicon understood the business situation of the company well. They offered pay-cuts and shorter work weeks to keep the workforce intact. They were experienced with cooperation, but as we will return to later they struggled with developing trust in the whole enterprise. The managers at Cylindertech were not very successful in creating a sound and constructive union leader – company management relationship. When the managers decided to build an information booth in the production premises this was done without the union leader’s approval. It is possible that the problem of informing the employees would have been solved differently if the company had internalized unionmanagement cooperation on enterprise development. In this case – as in many other 17 cases - both the union leader and the managements may have gained from a work practice where the union leader had been invited into the enterprise’s planning. To develop a proactive, competent, knowledgeable, and energetic union leader is unfortunately not sufficient. The Steeldrill case demonstrates how difficult the situation may be for the union leaders who have been invited and involved in the company’s strategic discussions by the managers. The union leader is experienced in enterprise development and understands the enterprise’s strategy and market. The litmus test is whether the union leader acknowledges why and how he must include and involve his member in process regarding company decision making. The case showed us how the union leader tried to sooth the rather annoyed members by explaining the managers’ difficult situation. He knows what the managers are dealing with and he knows that they are in a pressed situation. He knows this because he (as situated among them) is struggling with the same difficulties. After several years in the board room and after innumerable strategy meetings with the management he is able to se what one of the members asks for; namely a light at the end of the tunnel. The members don’t however see this “light” from the shop floor only. 6.2 The barrier between the representative and those he represents The union leader at Future Furniture is however aware of the fact that he is put in an awkward position. He continuously receive information that he knows the members are interested in receiving as soon as possible, but in many of the most important or even possible devastating situations for the members he is not allowed to tell what he knows before the day the management or the owners choose to make it public. This installs a barrier between him and the general members. The union leader is clearly annoyed by the members who in his view ever so often construct realities that lead to rumours and time-consuming misunderstandings. Although the Future Furniture case doesn’t say how the members relate to the union leader, it is possible that the union leader have separated him selves too much from those he represent in the sense that his focus and time is spent on activities detach from the members. A somewhat similar mechanism is present at Steeldrill. The management is annoyed by the union leader’s demands for information. The members perceive on the other 18 hand their union leader as running the errands of the management. Ironically, the union leader with its double loyalty ends up annoying all. You may also say that the union leader ends up in a hostage situation where he tries to meet the demands of both parties. The Cylindetech case demonstrates a barrier story easily recognizable. The union leader – who tries to develop into a good union leader - is not present in the production. He is often in meetings. His team workers would claim that he is always in meetings. This union leader is faced with the difficult situation of switching daily between being a mechanic equal to the members in the production and acting on the strategic arenas of the company. He is faced with - and has to cope with - the barriers that the union leader at Future Furniture just needs to acknowledge. In larger companies like Ferrosilicon, Power Electronic, and Future Furniture the union leaders are no longer part of the Workers Collective. They are clearly representing the workers and fight for their well-being, but they are able to do this on those arenas they see the opportunities. The union leader at Cylindertech is in an extra vulnerable situation since he has to relate to the demands of the workers on a daily basis. The union leaders at Ferrosilicon are facing a similar problem although most of the union leaders haven’t worked as operator for years. Unlike the union leader at Cylindertech they are not struggling with being present in the production. Because of the enterprise’s size they were faced with the challenge of representing the members in all areas of the enterprise. They have to meet different roles, opinions, and expectations. If we look at the members in the core operations at Ferrosilicon, there did not seem to be much of a barrier between the union leader and those he represented, but the union members situated further away from the core production line held other views and went into conflict with the union leader (and the rest of the union). 6.3 Coping with the barrier As we have seen, the gap between the union leader and the led may be widening in many cases. The reasons for this are several. One reason is an actual change of knowledge and perspective likely to take place as the union leader takes his game to a 19 different kind of field. Another is the change of perceptions that little by little seeps into their reasoning about each other, because they do not live the same worklife anymore. Last but not least, one reason is because their conversation is not frequent enough or intense enough to keep the mutual understanding alive. This third one is really an arena where they themselves can make a difference; where it matters what gets done. There are different ways of dealing with the barriers between the union leader and the members, and the union leaders develop their own, individual ways to prevent this schism to grow. As we read from the Cylindertech case, the union leader tried to meet the members by walking an extra round in the production premises when possible. The union leader didn’t leave the managers’ attempt of informing and communicating with the employees through a computer screen any hope. But in his search for a communication arena, the union leader himself made use of a social medium through the internet. It is possible that the information booth with its formality seems like a greater obstacle for the users than social medium on the internet, but what the case also illustrates is the need for an “information channel” between the union leader and the management. As Dirks and Skarlicki maintain, the dilemma the union leader encounters is that he may have to simultaneously meet the expectations of one party and violate the expectations of another (Dirks and Skarlicki 2004). Sustaining trust towards one party breaks the trust of another (Dirks and Skarlicki 2004). We do not disagree, but we have found that on many instances, the conflict is on the perception level rather than about the concrete realities behind them. A union leader enters a particular spot, and the view from there is not known to those he is representing, but this does not mean that he is not serving their interests anymore. But it does imply that managing the mutual perception between members and himself should form a key part of his workday. 6.4 Conclusion Industrial relations of Norway are quite unique due to the tradition for both negotiation and collaboration between employers and employees how manage to handle conflict negotiation and constructive cooperation simultaneously. And this 20 collaborative practice does not mean that you do not attend to the traditional “objective interests”, such as increasing wages, reducing working hours, and minimizing hazards. This is all well, but there is also room and perhaps need for a small word of caution. There is a risk involved as the union leader – company management relationship gets established, develops, gets strengthened and prospers, and that risk regards the need for attendance to and maintenance of the dialogue strength and shared reality perception between electors and elected. 21 References Bråten, S. (1973). Model Monopoly and Communication: Systems Theoretical Notes On Democratization. Acta Sociologica, 16, 98-107. Byrkjeflot, H. (2002). Ledelse på norsk: Motstridende tradisjoner og idealer? In A. Skogstad & S. Einarsen (Eds.), Ledelse på godt og vondt: effektivitet og trivsel (pp. 433 s.). Bergen: Fagbokforl. Cohen-Rosenthal, E., & Burton, C. E. (1987). Mutual Gains - A Guide to UnionManagement Cooperation. New York: Praeger Publishers. Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design : choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage. Czarniawska, B. (2007). Shadowing and other techniques for doing fieldwork in modern societies. Malmö, Oslo: Liber Universitetsforl. Deutsch, S. (2005). A Researcher's Guide to Worker Participation, Labor and Economic and Industrial Democracy. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 26, 645-656. Dirks, K. T., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2004). Trust in Leaders: Existing Research and Emerging Issues. In R. M. Kramer & K. S. Cook (Eds.), Trust and distrust in organizations : dilemmas and approaches (pp. XII, 381 s.). New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Eijnatten, F. M. v. (1993). The paradigm that changed the work place. Social science for social action: toward organizational renewal. Assen: Van Gorcum. Elden, M., & Levin, M. (1991). Cogenerative Learning. Bringing Participation into Action Research. In W. F. Whyte (Ed.), Participatory action research (pp. 247 s.). Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage Publications. Emery, F., & Thorsrud, E. (1976). Democracy at work / the report of the Norwegian industrial democracy program. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Social Sciences Division. Gilbert, D. T., & Malone, P. S. (1995). The Correspondence Bias. PSYCHOLOGICAL BULLETIN, 117, 21. Gill, C. (2009). Union impact on the effective adoption of High Performance Work Practices. Human Resource Management Review, 19, 39-50. Greenwood, D. J., & Levin, M. (2007). Introduction to action research : social research for social change. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications. Kochan, T. A., & Osterman, P. (1994). The mutual gains enterprise : forging a winning partnership among labor, management and government. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. Lysgaard, S. (1961). Arbeiderkollektivet: en studie i de underordnedes sosiologi. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. Malinowski, B. (1922). Argonauts of the Western Pacific : an account of native enterprise and adventure in the archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Academy of Management Review, 20, 709-734. Murnighan, J. K., Malhotra, D., & Weber, J. M. (2004). Paradoxes of Trust: Empirical and Theoretical Departures from a Traditional Model. In R. M. Kramer & K. S. Cook (Eds.), Trust and distrust in organizations : dilemmas and approaches (pp. XII, 381 s.). New York: Russell Sage Foundation. 22 Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (2008). The SAGE handbook of action research : participative inquiry and practice. London: SAGE. Rubinstein, S. A. (2001). Unions As Value-Adding Networks: Possibilities for the Future of U.S. Unionism. Journal of Labor Research, 22, 581-598. Stake, R. E. (2005). Qualitative Case Studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. XIX, 1210 s.). Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage. Toulmin, S., & Gustavsen, B. (1996). Beyond theory : changing organizations through participation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publ. Co. Yin, R. K. (1989). Case study research: design and methods. Newbury Park: Sage. Zucker, L. G. (1986). Production og trust: Institutional sources of economic structure, 1840-1920. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior : an annual series of analytical essays and critical reviews (pp. 53-111). Greenwich, Conn.: JAI Press. 23