Technology

advertisement

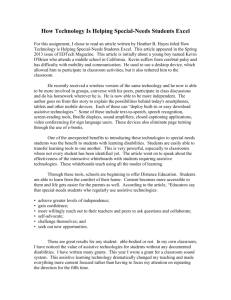

Technology Support Services in Postsecondary Education: A Mixed Methods Study Abstract. Technology has a profound effect upon the lives of students with disabilities. This mixed methods longitudinal analysis of technology supports began with nationally represented surveys followed by a qualitative cross case analysis and a longitudinal study of one site across four levels (coordinator, supervisors, support staff, and students) that underwent a 40% budget reduction. Results from all three phases clearly indicate that assistive technology was highly valued and supported by the participants in the study. The survey revealed that providing assistive technology was a top priority, the cross case analysis indicated that appropriate technological services and training reduced student dependency, and the longitudinal analysis across four levels revealed the coordinators priority to improve technology by updating hardware and software, training and reconfiguring staff, and collaborating with departments across campus continued to improve student success despite reduced funding and staff. Introduction Technology as a modern apparatus has numerous benefits and drawbacks. Proponents argue that technology equalizes or even liberates. Opponents say technology is a crutch, limiting imagination, and perpetuating compulsion. For many, technology is the only reason that they have survived. According to Gamble, Dowler and Orselene, technology supports can be positive or negative depending upon the individuals’ view of the world and how they envision the way they interact with society [3]. Seymour extends this view by focusing upon the relationship between social factors and self identity which can influence how assistive technology is embraced or rejected: “the self-identity of disabled people is informed by social factors: it is revealed in the user’s fears and joys, in their sense of autonomy, competence, independence, and in their insecurities and despair…This information holds the key to people’s attitudes and decisions about technology” [7]. In order to determine how technology is valued, postsecondary stakeholders’ perspectives of services were addressed in this three phase longitudinal mixed methods study which examined how technology supports the lives of students with 1 disabilities. Determining how technology is viewed required exploring the opinions of those who use and provide technology within the social context of the environment where the supports are offered. Technology has enormous potential to equalize without degrading the lives of students with disabilities in terms of mobility and active communication. Participants were particularly vocal about social stigmatization indicating that technology is one of the few tools to break down barriers allowing them to wholly interact within society. Postsecondary Technology Supports Over the past decade several empirically based studies have been conducted to determine the benefits of technology as a support for students with disabilities. Most focused upon primary and secondary education [2] while a few examined how technology was used in postsecondary environments [6,8]. This three phase study analyzed how technology is provided and embraced in postsecondary education. Phase-I was the statistical analysis of data from 1067 repeatedly administered national surveys from disability support coordinators. Phase-II included three purposefully selected exemplary support service sites with 17 interviews of coordinators and supervisors. Phase-III interviewed 23 individuals from four levels at one institution. The final analysis in this study incorporated the findings from all three phases as a way to draw out and express relevant conclusions related to technology in postsecondary education. Phase-I Survey Methods Phase-I statistically analyzed 1067 surveys using exploratory factor analysis [4] to determine if items grouped into the constructs. Reliability was assessed and regression was used to determine if technology was significantly different between 2-year and 4- 2 year institutions and over two points in time. Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to determine if institution type and time exhibited main or interaction effects. Survey Results Principal component analysis revealed that twenty-five items adequately loaded into four factors including Assistive Technology. Regression revealed there was a difference when institution type and survey years were compared, two-year and four-year institutions were significantly different in Assistive Technology but not over time. Multivariate analysis revealed no interaction between institution type and time and only the main effect for institution type (F=18.50, 4 df, p=.000). Two-year and four-year institutions differ on the level of technology supports provided. Cross Case Methods The qualitative cross case analysis [9] in Phase-II emerged in part from inherent survey limitations, the inability to explore how technology was perceived and valued. The research questions used for Phase-II were: (1) How are technology supports provided to students with disabilities in exemplary postsecondary institutions? (2) How does leadership, staff cohesion and collaboration relate to technology supports in postsecondary institutions? Seventeen interviews generated 436 pages of raw transcripts that when initially analyzed revealed 22 open codes used to create reports that helped formulate six major dimensions. This paper focuses specifically on technology as a support for postsecondary students in two categories, innovative techniques and barriers. Cross Case Results 3 The three colleges all embraced technology as a means of providing access for students with disabilities. Although the sites were remarkably similar with regards to software and hardware, differences in legislation that drove funding was markedly different. The cross case analysis revealed that funding and legislation had a direct effect upon the sophistication of technology, how often it was updated, and if there was staff to train and support students (see Table 1). Most revealing was how technology was used. At El Camino College, JawBone middleware was used to connect software such as Dragon Naturally Speaking, Joz, and Handi-Word for students with low vision. According to the technology supervisor “some students who do not type fast or have limited use of their hands can use Handi-Word. So now a student who has a hard time using their hands and cannot see can use voice recognition. They can also use Jawbone to perform voice commands, and have Joz read material back to them. By using multiple programs linked by middleware, the possibilities increase exponentially. Dragon, JunText, Joz and Handi-word can all be linked and then they can be used with word processing and spreadsheet programs like Microsoft Word and Excel.” El Camino was also the only institute to use switching devices such as Easy-Keys for students. The technology supervisor indicated that Easy-Keys “is just a basic switch for retainers, for your chin, your foot, it is a constant control. If someone is able to blink, they can use this technology.” The technology trainer for the High Tech Center stated “with switching technology you can control, you can type, it has word-prediction, mouse-controls, everything you can do on any other computer all linked with the switch technology. I have seen some of our students with physical disabilities that can actually type faster using this technology than actual keyboards; it’s pretty amazing what it can 4 do.” According to the technology supervisor “We have Pen-Mouse that uses infrared technology for on-screen keyboarding that can be linked through Jaw-Bone to word prediction software. Students can use this infrared technology with a head mouse, typing, word prediction, online access.” The infrared hardware and software which costs between two and three thousand dollars is excellent technology for those who do not have limb control. Unfortunately, learning to use infrared software to make the keyboard bigger or smaller, make it to click faster or slower or have a customized alphabetic keypad requires intensive training, especially for a student who has never typed before. In summary, technology support services varied considerably, even at exemplary sites. Many influences effected technology supports including funding, commitment, training, dedication, time, and leadership direction. All three coordinators had a high regard for technology and encouraged staff and students to use it whenever possible and clearly El Camino’s coordinator placed technology as the highest priority. Phase-III Longitudinal Methods Phase-III longitudinal analysis emerged after California reduced funding for postsecondary education by 40%. This reduction was devastating to assistive technologies which are often viewed as supplementary. By examining El Camino longitudinally, one could better understand how funding affected technology services from the perspectives of the coordinator, supervisors, support personnel and students. Phase-III was driven by the following two research questions: (1) How has technology at an institutional level changed as a result of declining funds? (2) Are there differences in the way students and staff view the effectiveness of technology support services? 5 The longitudinal phase relied upon 23 interviews digitally recorded, and transcribed generated 406 pages of transcripts used as sources of information to create 24 open codes [1] used with NVivo qualitative software. Code reports were then generated to determine the relationship between codes and as a way to examine similarities and anomalies amongst the interviews. This selective level of analysis resulted in the four core categories [5] for this study operationally defined as “Changes, Leadership, Technology and Interpreters”. Longitudinal Results The coordinator indicated that after the budget reduction “technology was a low priority statewide when compared to mandated disability services”. When funds were reduced to postsecondary institutions, “money slated for technology improvements were diverted to pay for personnel and other disability related services.” Unlike other coordinators in California, El Camino placed assistive technology as a top priority. “I always had some money set aside from the categorical dollars to put towards the High Tech Center until the severe cuts happened. Now I rely upon donations and alternative funding to offset costs to keep the technical side maintained. “Each department is working to become proficient in technology so that they can better accommodate and serve the students.” The counselors, the learning disability specialists, interpreters, mobility specialists, even secretarial support have a good understanding of the various technologies that are available across campus. The most striking change to technology after the budget reduction was that students were no longer trained individually, they were taught to use technology in groups which provided opportunities to practice technology in the context of completing 6 assignments for classes through trial and error with support. The technology specialists indicated that software like Digital Text, Kurzweill 3000, and Dragon Naturally Speaking are wonderful tools but are expensive and require considerable time for training. Ultimately, the students are the clientele and consumers of assistive technology in postsecondary education. Their views corroborated what the coordinator, the supervisors, and staff said about how important assistive technology is as at reducing barriers. Further, students indicated that the High Tech Center was successful at maintaining services despite drastic financial constraints. These findings added credibility to several emergent themes. One student with visual, gross, and fine motor disabilities stated “being able to get around campus and learning all the technology offered by the new computer programs has made life easier”. El Camino was clearly supporting students’ technology needs. “I come in to the Special Resource Center. This helps because I don't have a computer at home that can read the material to me, so that's a problem. The only way that I can use a computer with a scanner is to do it here. I use Dragon Naturally Speaking, I listen to Kurtzweil 1000 and Jaws, and use the scanner with books.” Another student said “I have my own Gordie which is like a pair of goggles with a control box which is connected to the goggles with LCD screens that are over the eye. The unit has a camera in the front and so it really enlarges the images. And I've got a toolbox that varies the contrast so I can magnify things.” “Learning about technology helped me get a job. And the text program in Jaw's latest edition is helping me pass my classes. This is helping me to build up my self-confidence to become a better self advocate.” 7 One student with virtually no body control and is blind summed up the importance of technology “Being able to get around campus and the technology offered by the new computer programs makes my life a little more independent. Certainly that may be the case for all disabled individuals, but especially for me. I think all around they are supporting the students well. I'm learning Dragon Naturally Speaking, and I listen to Kurtzweil as well as Jaws.” Conclusions The purpose of this study was to gather information about technology services nationally, explore the impact of assistive technology at exemplary postsecondary institutions, and determine how technology services changed as a result of budget constraints over time. The statistical analysis revealed that two-year institutions offered more technology hardware, software, training and access than their four-year counterparts. The cross case analysis revealed that technology services were affected by funding and two sites with disability specific support had more staff, equipment, facilities, and time available for students requesting technology supports. The longitudinal study revealed that despite a 40% budget reduction, services were maintained by streamlining practices, reorganizing the format, and changing the content of technology training and services which resulted in more efficient and successful assistive technology for the students. This was only possible by completely transforming how assistive technology was provided. Results from all three phases combined clearly indicate that assistive technology was highly valued and supported by all participants. Each of the exemplary sites had coordinators who promoted technology training and support as a useful tool for providing 8 access and improving academic performance. Technology as a priority instigated by the coordinator and supervisors carried over to the staff and students who in turn had high expectations for mastering the tools that helped support their education. References [1] K. Charmaz, Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis; Sage, Thousand Oaks, California, 2006. [2] T. Christ and R. Stodden, Advantages of developing survey constructs when comparing educational supports offered to students with disabilities in postsecondary education. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 22 (1) (2005), 23-31. [3] M. Gamble, D. Dowler and L. Orslene, Assitive technology: Choosing the right tool for the right job, Journal of vocational rehabilitation 24 (2006) 73-80. [4] J. Hair, R. Anderson, R. Tatham and W. Black, Multivariate data analysis with readings (3rd ed.); Macmillan Publishing, New York, 1992. [5] Y. Lincoln and E. Guba, Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.) The Sage handbook of qualitative research; (191-214); Sage, Thousand Oaks, California, 2005. [6] K. Roberts and R. Stodden, The use of voice recognition software as a compensatory strategy for postsecondary education students receiving services under the category of learning disabled, Journal of vocational rehabilitation 22 (1) (2005) 49-64. [7] W. Seymour, ICTs and disability: Exploring the human dimension of technological engagement, Technology and Disability 17 (2005) 195-204. [8] M. Sharpe, D. Johnson, M. Izzo and A. Murray, Journal of vocational rehabilitation 22 (1) (2005) 3-11. 9 [9] S. Sze and S. Valentin, Self concept and children with disabilities, Education 127 (4) (2007) 552-557. 10