War Rhetoric in India and Pakistan

Propaganda and the Information Revolution: The Effect of Communications Technology on War Rhetoric in India and Pakistan

Priya Jhingan

Engineering 297A

Ethics of Development in a Global Environment

Professor Bruce Lusignan

2

Propaganda and the Information Revolution: The Effect of Communications Technology on War Rhetoric in India and Pakistan

Introduction

For the past half-century, India and Pakistan have experienced continuous political, economic, and military tension. While religious differences have played a role in exacerbating conflict, government-imposed propaganda has undoubtedly cast its shadow on the situation. Interestingly, the information revolution, which has recently begun to permeate the borders of the two nations, has revolutionized the way propaganda spreads in times of tension. By introducing advanced communications technology into

Pakistan and India, the information revolution has the paradoxical effect of helping and harming propaganda.

My interest in the development of communications in South Asia began earlier this year, when I compiled an analysis of the information revolution in rural India for

EDGE 297B during winter of 2004. This quarter, I have applied my analysis to the context of war and conflict in South Asia. This paper will evaluate the effects of advancing communications technology on war rhetoric and propaganda in Pakistan and

India. I will begin with a brief overview of the India-Pakistan conflict and the information revolution in these two nations. I will then proceed with an analysis of several types of communications technologies and their effects on propaganda.

A History of Conflict

The troubled history between India and Pakistan dates back to 1947, when Britain announced that it would partition the colony, known as “Hindustan,” into the Hindu-

3 dominated India and newly-created Muslim state of Pakistan. Violence erupted as Hindus and Sikhs escaped from new Pakistani territory and Muslims escaped from the Indian territory. In fact, my grandparents (both paternal and maternal) were among those who escaped from the Pakistani part of Punjab (one of the territories that was split among

Pakistan and India). Fear and despair was the norm as countless citizens were displaced from their homes and forced to migrate to unfamiliar territories amidst hostile conditions.

Survival was the goal, as men, women, children, and even whole families were taken out of buses and massacred. Fortunately, my grandparents survived; but approximately

500,000 died during the Partition.

Since then, religious tension as well as bloodshed over the disputed region of

Kashmir has dominated the affairs of the two nations. When British India became independent, it was supposed to separate into two parts. Areas consisting of at least seventy-five percent Muslims were to join Pakistan, while the rest of the territory would go to India. However, this arrangement excluded part of the territory. The British government ruled India with two administrative systems, ‘Provinces’ and ‘Princely

4

States.’ Provinces comprised sixty percent of the territory while Princely States comprised forty percent. Provinces were British territories completely under British control, and Princely States were states in British India with a local ruler or king. While these rulers ultimately reported to the British Empire, they were more autonomous than any rulers in the Provinces.

The territory going to India and Pakistan in the Partition did not include the

Princely States, which were at liberty to determine their own future. They could join

Pakistan, India, or remain independent. One such Princely State was Kashmir. The

Maharaja of Kashmir, Hari Singh Dogra, decided to preserve the state of Kashmir and remain autonomous from both India and Pakistan. When Pakistan sent tribal leaders to talk to Kashmir about their decision of autonomy, the Indian government viewed this as a sign of invasion and sent their troops to help defend the state of Kashmir. This was the first war between India and Pakistan over Kashmir, and ended with Pakistan controlling thirty-seven percent while India controlled sixty-three.

A second war involving Kashmir occurred between India and Pakistan in 1965, but resulted in a stalemate. Tensions have only risen since then, especially recently with the looming fear of nuclear involvement in wars on the part of both nations.

Propaganda

Regardless of the nature of its government, every nation is prone to propaganda, especially in times of tension. In his book, Propaganda and Psychological Warfare , T.H.

Qualter defines propaganda as the deliberate attempt by some individual or group to form, control, or alter the attitudes of other groups by the use of instruments of

5 communication, with the intention that in any given situation the reaction of those influenced will be that desired by the propagandist.

While “instruments of communication” generally refer to mass media, they should also include things like statues, coinage, and forms of interpersonal communication. Most importantly, propaganda has the following factors:

1.

It is deliberate.

2.

It aims to control or alter people’s attitudes.

3.

It aims to produce predictable behavior by those whose views are altered.

4.

It does not depend on violence or bribery.

Propaganda operates through the (often subtle and covert) transmission of ideas and values. When nations are in crises, their governments often use propaganda to influence the beliefs and views of their citizens. It is important to remember that the techniques of propaganda are neutral. While propaganda is often used for bad ends, it is nearly as often used for good ends. Most experts who study propaganda have identified seven basic propaganda techniques:

1. Name-Calling : The name-calling technique links a person or an idea to a negative label. The user of this technique hopes that the negative connotation associated with the name will cause the audience to overlook any available evidence and reject the labeled person or idea. An example of this technique is the use of the label "Communist"

6 or "Commie" by Senator Joseph McCarthy and Congressman Richard Nixon during the

Red Scare in the 1950s.

A more subtle form of name-calling involves words that are selected because they invoke certain emotions. For example, propaganda by opponents of a budget cut might portray conservative congressmen as "stingy", because of the emotional reaction most people would feel upon hearing that word.

2. Glittering Generality: The Glittering Generality technique is the opposite of name-calling. This technique associates a person or an idea with "virtue words." These words, (such as democracy, right, Christianity, good, proper, patriotism, science) are chosen because of their positive connotation or positive emotional impact. The aim of glittering generality is to influence the audience to accept the person or idea based on the acceptance of the virtue words and not based on the evidence.

3. Transfer: This technique is similar to the technique of glittering generalities.

The propagandist who uses transfer hopes to link his ideas to a higher concept such as science or religion. Except, in transfer, the propaganda is spread through symbols, not the use of words. For example, a political activist who ends her speech with a prayer is using transfer. By invoking religion amidst her political ideology, she is hoping to demonstrate that God sanctions her ideas.

4. Testimonial: The testimonial technique is a technique widely used in advertising and in politics. It connects a person, idea, or product to a celebrity, regardless of that celebrity's qualifications to form a good opinion. The propagandist using this

technique hopes the celebrity will increase popularity of the product or idea and thus cause its acceptance.

7

5. Plain Folks: This is a technique designed to demonstrate how a person, product, or idea is "of the people." Presidential candidates often use this technique to amass popularity. George Bush's "love" of country music and pork rinds is a good example.

6. Card-Stacking: Card stacking is a technique in which an apparently logical argument is employed, usually to incite fear. Card stacking is used in conjunction with the other techniques, which are often used to hide logical fallacies within the main argument. In order for a card-stacking appeal to be effective it must meet three criteria:

(1) The more fear it incites, the better; (2) The appeal must not leave the audience completely hopeless; (3) There propagandist must suggest an action that will relieve the danger.

The following quote from a speech by Adolph Hitler is a good example of cardstacking:

The streets of our country are in turmoil. The universities are filled with students rebelling and rioting. Communists are seeking to destroy our country. Russia is threatening us with her might, and the Republic is in danger. Yes - danger from within and without. We need law and order! Without it our nation cannot survive.

(Adolf Hitler, 1932)

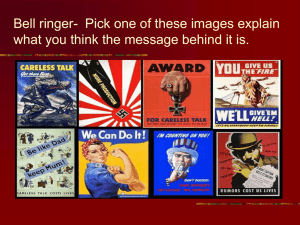

7. Band Wagon: A propagandist uses the band wagon technique to appeal to mass psychology. This technique tries to convince the public to do something because

“everyone else is doing it.” A good example is the “We can do it!” poster designed to encourage women into work during World War II. In fact, this poster continues to be used effectively today by labor unions and women's groups.

8

Band wagon propaganda

There are many ways that the propagandist can use these techniques to influence the audience. In the context of military propaganda, the government often uses censorship of opposing ideas on the basis that these ideas incite fear (card-stacking) or transfer biased information. In my paper, I will discuss the censorship of TV and films, which is one of the prevalent forms of propaganda in both India and Pakistan.

Censorship as a Form of Propaganda

Censorship is the type of propaganda classified as “selective omission,” which is the process of choosing and selecting from a variety of facts only those that most effectively strengthen and authenticate the propagandist’s viewpoint. Success depends on how successful the propagandist, in this case, the government, is in omitting opposing viewpoints.

Censorship of certain products of mass communication is a powerful tool for propaganda. When the propagandist is the government, it is most powerful, because the

9 government often has extensive control over forms of media, such as cable TV and radio operation. In a democracy such as India, the people can and ought to make a strong case against censorship because it violates the fundamental rights of freedom of speech and expression. In a military dictatorship, such as Pakistan, the case against censorship is not as strong since the dictatorship has the self-declared “right” to do what it wants.

Regardless of the governmental context, however, censorship has devastating consequences on the marketplace of ideas represented in society. By inhibiting a free flow of information that is vital to healthy public discourse, censorship harms the citizens’ ability to make their own, well-informed decisions. The advanced communications technologies that the information revolution has brought to India and

Pakistan have yielded unprecedented results on the government’s use of propaganda.

Before I begin a detailed discussion of such effects, I will provide a brief overview of the information revolution in the two nations.

Advancement Amidst Tension

Although much of Indian and Pakistani affairs have revolved around their interpersonal conflict, both countries have undoubtedly experienced an increase in the availability of advanced communications technologies. Most notable is the increase of availability in telephones, television sets, and the internet. Because both countries exhibit varying degrees of advancement with respect to each type of technology, I will analyze them separately before reaching a general conclusion. Tables 1 and 2 (which I compiled from data taken from studies conducted by the World Bank) provide important data

10 relating to the increase of new information and communications technologies, known as

“ICTs.” The first contains data for Pakistan, and the second for India.

The development of Communications in Pakistan

Table 1: Development of ICTs in Pakistan

ICT infrastructure and access

Telephone mainlines

Per 1,000 people

1995

17

61

0

In largest city (per 1,000 people)

Mobile phones (per 1,000 people)

International telecommunications

Outgoing traffic (minutes per subscriber)

Cost of call to U.S. ($ per 3 minutes)

Radios (per 1,000)

Television sets (per 1,000)

31

N/A

102

51

Computer and the internet

Personal computers

Per 1,000 people

Installed in education (thousands)

Internet

Users (thousands)

Monthly off-peak access charges

Service provider charge

Access charge

ICT expenditures

Total ICT ($, millions)

ICT as % of GDP

ICT per capita ($)

N/A

N/A

N/A

3.5

N/A

.2

N/A

N/A

2001

23

62

6

53

3.54

105

148

4.1

N/A

500

12.6

0.20

N/A

N/A

N/A

Overall, there is little increase in the availability of radios and mobile phones in

Pakistan. While it is true that mobile phones have at least been introduced into the communications market (in 1995, no one used mobile phones while in 2001, six people out of every 1,000 did), six out of 1,000 people does not represent a significant portion of the population. On the contrary, telephone mainlines experienced a notable increase in existence.

11

While only 17 out of 1,000 people in Pakistan had their own lines in 1995, the number rose to 23 in 2001. However, the two increases that are most relevant to my discussion topic on propaganda are the dramatic increase in availability of television sets and the internet. In Pakistan, from 1995 to 2001, the number of television sets per 1,000 people increased from 51 to 148! The consequences of such a large increase in the availability of TV has staggering effects on the spread of propaganda, which I will discuss in further detail in the next section.

The development of Communications in India

Like Pakistan, India also experienced an increase in telephone communications.

However, India’s was a much larger increase, from 13 out of 1,000 in 1995 to 38 out of

1,000 in 2001. While increase in usage of internet was explosive (especially in the educational sector), the increase in availability of TVs was less than in Pakistan’s case. In

1995, 61 out of 1,000 people owned TV sets, and in 2001, this number rose to 83. On the other hand, in Pakistan in 2001, 148 out of 1,000 people owned TVs. This highlights the differing priorities of both governments; while India stressed development of the telephone industry, Pakistan focused more on television. This difference has an important impact on the way that both governments have spread propaganda.

12

Table 2: Development of ICTs in India

ICT infrastructure and access

Telephone mainlines

Per 1,000 people

In largest city (per 1,000 people)

Mobile phones (per 1,000 people)

International telecommunications

Outgoing traffic (minutes per subscriber)

Cost of call to U.S. ($ per 3 minutes)

Radios (per 1,000)

Television sets (per 1,000)

Computer and the internet

Personal computers

Per 1,000 people

Installed in education (thousands)

Internet

Users (thousands)

Monthly off-peak access charges

Service provider charge

Access charge

ICT expenditures

Total ICT ($, millions)

ICT as % of GDP

ICT per capita ($)

1.3

23.6

250

N/A

N/A

1995

13

95

0

29

N/A

119

61

7,250.0

2.1

7.8

2001

38

136

6

14

3.20

120

83

5.8

238.7

7,000

10.0

0.18

19,662.0

3.9

19.0

Propaganda and Communications Technology

The two most effective means of spreading propaganda through technology are television and the internet. While radios can also be effective, and in fact are more widespread in India, radio broadcast lacks the visual aspect that makes TV and internet so valuable to propaganda. TV, especially, allows for more subtle forms of propaganda, such as displaying selected photographs and playing one-sided commercials. The greater accessibility to and development of the television industry, especially in Pakistan, has interesting effects on propaganda in the nation.

13

Banning TV stations

Despite the rift between India and Pakistan, citizens of both nations nevertheless like to watch each other’s movies and TV channels. Recently, however, both governments have banned the other nations’ satellite TV channels, with the excuse that such channels are spreading unnecessary propaganda. This has been occurring in a number of different instances. For example, in June of 1999, the Indian minister in charge of information and broadcasting, Pramod Mahajan, announced the decision to ban

Pakistan TV by cable operators after inaugurating a new digital recording studio at

Doordarshan studio at Worli, India.

This ban on Pakistan Television programs was allegedly due to the ongoing fight involving the “vilification campaign against India, especially in connection with the

Kargil situation." This is in reference to the Indian military operations that are currently occupying the state of Kashmir, where independent international media have been banned, according to Agence France-Presse (AFP). Mahajan remarked,

We conducted an analysis of the news and other programmes aired by the PTV since the Kargil episode started. The channel has been broadcasting false and malafide news, which might create a confusions in viewers mind. Moreover, the message being given by PTV might lead to internal insurgency in India. The

Government cannot tolerate this anymore and has to take firm decision. We have issued orders this afternoon banning the channel in the country.

This quote shows how Mahajan never explains the analysis he and his board conducted, or how Pakistan Television is contrary to the democratic ideals of the country.

Most importantly, even above nationalism, is the need for a democratic country to uphold the rights of its citizens. Instead of doing what is best for their country, Mahajan and the

14 censor board have tried to impose their beliefs on the people of India. They have clearly used censorship as a means of spreading propaganda.

Furthermore, Mahajan’s outrageous claim that Pakistan Television might lead to internal insurgency within India has no foundational evidence or appropriate analysis.

There are millions of people in India, and to assume that a channel on television can cause widespread insurgency is simply absurd. Mass media around the globe always has the danger of being biased or untrue, but freedom of speech and freedom of the press is vital to a functioning democracy where all viewpoints must be heard. Thus, there is no reason for the Indian government to ban Pakistan Television.

Furthermore, in the context of Kashmir, this ban has enabled a thorough news blackout in regards to issues of human rights violations. In order for the Kashmir citizens to know what is truly best for them and for their state, they must be exposed to all sides of this story. This will occur only through a free marketplace of ideas where none of the television stations are banned on the basis of “spreading propaganda.”

In the past, India has been known to jam the signals for Pakistan Television stations using their satellites to cause interference. At the same time, India’s television stations have been freely available in Pakistan. Furthermore, it was ordered that the government would punish those who do not uphold the ban order. In fact, Mohajan had advised state governments to summon the police, asking them to take action against cable operators who ignore the order.

This issue is also addressed in a letter from the executive director of the

Committee to Protect Journalists, known as CPJ, Ann K. Cooper, to the Prime Minister of

India,

Atal Behari Vajpayee. The letter reads:

15

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) is concerned over your administration's recent decision to ban the transmission of Pakistan Television

(PTV) within India's borders. On June 2, after the launch of India's air campaign in Kashmir's Kargil region, Information Minister Pramod Mahajan announced that cable operators across the country are prohibited from broadcasting PTV,

"which has launched a vilification campaign against India, especially in connection with the Kargil situation." The minister added that the ban would remain in effect pending further instructions from the central government.

As an organization dedicated to the defense of press freedom around the world,

CPJ urges your administration to rescind the ban on PTV. Such action is in direct contravention of Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that "Everyone has the right to... seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers."

CPJ is particularly troubled by Mahajan's instructions to the state governments that they must order police to take action against those cable operators who violate the ban. We also note that in many parts of Jammu and Kashmir, citizens receive PTV without cable access, and hope authorities will not punish those who exercise their right to choose their source of news. We thank you for your attention to this matter, and await your response.

CPJ, an international organization dedicated to protecting journalists’ right to free speech, shows how such censorship is contradictory to the spirit of the Human Rights

Declaration. Specifically, Article 19 of the Declaration states that everyone has a right to seek information from various sources regardless of frontiers. Thus, according to the

United Nations and the Human Rights Declaration, censorship of PTV conflicts with the democratic ideals of India’s government.

Unfortunately, Pakistan’s government is now a military dictatorship. In October of 1999, the Pakistani military deposed Prime Minister Sharif and established its own dictatorship. Consequently, Pakistan’s government does not have the same “duty” to its citizens as a democracy would, and it is easier for the Pakistani government to censor media and justify this sort of censorship. Thus, in response to both rising tensions with

16

India and India’s ban on PTV, the Pakistani government decided to ban all Indian satellite TV stations.

For example, Naubahar Asim, a Pakistani housewife, has again started watching

Indian films on a videocassette recorder - the only means of entertainment available to her after the government banned Indian satellite channels amid war rhetoric between the rival nations.

The number of cable and satellite television operators in both Pakistan and India has increased dramatically over the past five years. Naubahar's home is one among thousands that receive over a dozen Indian television channels from cable television operators, proof that local residents' interest in India's cinema and entertainment world thrives despite the political gulf between New Delhi and Islamabad.

However, after the ban on Indian channels, which was imposed on December 29,

2003, Pakistanis are left with only some government-controlled local channels and a few western English sports, news, and film channels. Since a majority of viewers do not understand English, these channels are of little use to them. On the other hand, the language of the Indian channels is Hindi, which is similar to Pakistan's national language,

Urdu. Thus, for many, TV has become boring ever since the government imposed the ban.

Fehmida Majeed, a Pakistani in her 50s, says that as India's and Pakistan's leaders continue their conflict, she will miss the Indian hit dramas, Kahani Ghar Ghar Ki (The

Story of Every Household) and Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thee (Once the Mother-in-law Was a Daughter-in-law), which used to be telecast from Monday to Thursday nights.

In its ban, the Pakistani government asked the cable television operators to immediately

17 stop relaying Indian television channels because "Indian TV channels beamed through satellite in Pakistan, as well as beamed by Star satellite channels, are propagating injurious material against the security of the country".

The chairman of the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority, Major-General

Shahzada Alam Malik, is responsible for regulating the cable television business. He remarked that the decision to ban Indian TV had been taken in protest against the Indian decision to block Pakistan television programs.

The Indian government initially banned Pakistan TV after the December 13 terrorist attack on its parliament. India blames the attacks on Pakistan-linked militants, a charge that has sent already tense ties to an all-time low. Along with banning PTV, the

Indian government severed bus, rail and air links and barred the use of its airspace by

Pakistani airliners, and reduced the high commission staff in Islamabad to half. In response, Pakistan has restricted its airspace for Indian airliners, reducing its staff to half and banning Indian channels in the country.

The banning of Indian channels was the first-ever decision of the sort taken by the new Pakistan government, which did not retaliate to earlier Indian government decisions blocking the transmission of Pakistan Television. In earlier cases, there was more danger of propaganda involving Indian channels. For example, Islamabad did not respond to what critics say was the hacking of the English-language daily Dawn website during the 10-week bloody military standoff in the Kargil area in early 1999, or when an

Indian airliner was hijacked in Kathmandu. During these conflicts, all the Indian channels were reporting Indian government allegations involving Pakistan.

18

But at this time, the Pakistani government did not bar Indian channels. It did not bar them because it did not have the capacity to do so. Many Pakistanis were watching

Indian channels through cheap dish antennas installed on their rooftops, making it impossible for the government to remove all of them. But after many of these channels were digitized and could only be seen through expensive decoders, authorized cable operators entered the market and with their own small television networks. They were responsible for providing about two dozen channels to urban consumers throughout

Pakistan.

Furthermore, before the ban, every cable operator had its own channel showing popular Indian movies. In June of 2000, the government started issuing licenses to these cable television operators under the condition that that they would "respect national sovereignty and integrity and promote religious, social, cultural and political values of the people of Pakistan.” This clause itself is an example of propaganda. The Pakistani government used its control over the television industry to influence the views of its citizens. The advancement of television technology from cheap dish antennas to satellite broadcasting actually enabled the government to have stricter control over the TV stations, which they could use to spread propaganda. To many cable industry officials, the government’s mandate was a vague condition that became clearer when the Pakistani government imposed the recent ban. The advancement of communications technology made it easier for the government to censor information and ironically worked to disadvantage the Pakistani people.

19

The previous technology: a cheap dish antenna haphazardly installed on a rooftop.

Moreover, TVs are more widespread in Pakistan than in India. As a result, the censorship of Indian TV channels has a greater impact on the Pakistani people than the

Indian government’s corresponding censorship. According to official estimates, there are

826 registered cable operators in the country, and two million subscribers. But the figure could be much higher because many cable television providers continue to operate beyond government control. The Asia Times notes that as the political tit-for-tat between

India and Pakistan spills into the fields of media, both the Indian and Pakistani governments have imposed blockades on each other's channels after dubbing their programs "propaganda-intensive.”

On many occasions in the past, both countries have agreed, as in June 1997, that they would take all possible steps to prevent hostile propaganda and provocative actions against each other. Furthermore, in July 1989 both governments agreed to exchange radio and television programs, and vowed to facilitate exchange of newspapers and allow

20 participation in each other’s film festivals. However, neither country has upheld this agreement. The agreements wait to be implemented and the lucrative trade of pirated movies and illegal reception of satellite signals is in the hands of the smugglers. For example, an Indian news magazine that sells for 10 rupees (around twenty US cents) in

New Delhi costs four dollars in Islamabad.

Although both nations have banned each other’s satellite stations in the grounds that they promote propaganda, neither has explained any relevant analysis. Salman

Hummayun, director of the non-government Consumer Rights Commission of Pakistan, notes that both governments are resorting to extreme measures without defining what propaganda is and if it has increased during explosive situations like the present one. He further comments that the situation on information exchange cannot be improved unless both countries employ modern propaganda analysis techniques like system message analyses and content analyses. Using these tools, the government can quantify the amount of propaganda and then inform the public of the results.

Banning films

The film industry is prominent in South Asia, especially in India, which has the largest film industry of any nation in the world. While most of the films dished out by its mass-appealing industry called “Bollywood” (a concatenation of “Bombay,” the central city involving hosting the film industry, and the United States’ Hollywood) are nonconfrontational about issues of conflict in the nation, the independent film industry is more aggressive. For example, the well-known documentary film-maker Anand

21

Patwardhan has recently made a film entitled War and Peace that openly discusses governmental manipulation and other controversial issues.

As a result, the Indian government has banned the film and will not allow its screening in Indian theaters. Indian movie analyst Ammu Joseph argues that India's “selfappointed culture police” have recently taken to imposing “censorship by mob” on anything that fails to fit into their narrow view of morality and “Indian-ness”. While the

Indian government has proposed to soften its current censorship laws concerning films, the liberalization of the censorship regime will most likely not extend to the political content of cinema. The recent experience of Patwardhan indicates that the Central Board of Film Certification (the CBFC) may not be able or willing to free itself from the shackles of political correctness as defined by the government of the day.

Anand Patwardhan joining others in protest at the

Mumbai International Film

Festival, India, 2004

A poster for Patwardhan’s banned film, War and Peace

22

According to a press release issued last week by Patwardhan, the Censor Board has mandated six cuts in his award-winning documentary film, War and Peace .

Revolving around the ideas of Mahatma Gandhi, the three-hour film, which won two major awards at the Films Division's Mumbai International Film Festival in February

2002, presents a convincing argument favoring peace over war.

The film took three years to complete and concerns nuclear tensions involving

India, Pakistan, Japan and the US. Its specific context is framed by the nuclear tests in

India and Pakistan in May of 1998 as well as the terrorist attacks in the U.S.A. on

September 11, 2001. The film documents the growth of peace activism across the world in the face of global militarism, nuclear proliferation, and war.

Arguing against religious "fundamentalism" and jingoistic "patriotism," the film shows that both extremes are two sides of the same coin. In fact, the film discusses many issues involving war that are not often discussed or publicly known. For example, in a forewarning about the dangers of nuclear war, it highlights the horrors of Hiroshima and

Nagasaki and chronicles the health and other problems of people living near nuclear testing and mining sites. These problems pertain directly to the Indian public, who is unaware of the dangers of living near nuclear test and development sites. By discussing these topics in his film, Patwardhan increases awareness of the public on issues that the government would not autonomously bring up.

The film also specifically covers the ongoing conflict between India and Pakistan.

Ammu Joseph, journalist for the Index for Free Expression Magazine, notes that despite the gravity and potential grimness of the subject, and its hard-hitting, if indirect, commentary on warmongers everywhere, Patwardhan’s film comes through as essentially

23 humane, focusing as it does on the desire for peace among ordinary citizens on both sides of the contentious border between India and Pakistan.

Putting forth well-founded arguments in favor peace, War and Peace has appealed to a wide range of viewers. When this film was shown before its ban in a premier in Bangalore, India, the audiences packed the hall on two consecutive days, clearly absorbed and moved by what is undoubtedly a powerful film. In fact, many stayed on for discussions with the film-maker after the screenings, despite the length of the film, the lateness of the hour and the threat of rain. Several who saw the premier on the first day returned for a second viewing the next day.

Many of the viewers were teenagers, who initially thought they would be bored by a documentary. However, Patwardhan’s film is so powerful that viewers of all ages identified with it, each relating to the message of peace. For example, a teenager who had brought along a novel to the theater, expecting to be bored by the documentary, publicly admitted that he had not even opened his book. After its viewing, a number of people expressed the hope that the film would be widely distributed so that its message of peace could be effectively disseminated. However, the Censor Board has tried its best to prevent this from happening.

The CBFC has mandated at least six cuts in the film, which must be made if the film is to be shown anywhere else in India. Of the major cuts demanded by the Board, the most astounding involves the deletion of all visuals and dialogues of political leaders, including the prime minister and other ministers. Furthermore, the Censor Board did not specify any particular scenes with ministers, since no specific visuals or dialogues have been identified as objectionable. Thus, the Censor Board’s aim is to ensure that no

24 politician is to be seen or heard in the film. Patwardhan notes that "the Censor Board deems it illegal to report the speeches of ministers, prime ministers and political leaders."

The repercussions of the deletion of references to political leaders are detrimental. By forbidding this type of reference, the Censor Board is not allowing its public to be aware of potential problems with the government. In a democracy, film-makers like Patwardhan are supposed to have the right to question the government openly in the public. Their works add to the flow of information that the public needs in order to form appropriate opinions and make good discussions.

However, the Censor Board is only interested in upholding the views of the government, making it difficult for anyone who opposes its views to be heard. This type of selective omission is the linchpin of propaganda through censorship. By omitting opposing views, the government-controlled Censor Board is trying its best to rule out opposing opinions.

Two other cuts ordered by the Board are also quite astonishing. One calls for the deletion of the entire sequence featuring a neo-Buddhist Dalit leader's condemnation of the 1998 nuclear tests. The film includes his critical commentary on the choice of the

Buddha's birthday for the explosions and the use of the Buddha's name in the military code proclaiming the success of the tests. The government’s use of Buddha’s name could be a highly controversial issue (if openly discussed in the public forum) in view of the fact that the Buddha was always unarmed and has long been identified as an advocate of peace.

The second deletion demands the expunction of a Dalit song that describes the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi by a Hindu fundamentalist. For years, the government

25 has tried to hide the possibility (which is actually accepted as fact by a majority of experts) that it was a Hindu fundamentalist who assassinated Gandhi. Because the government is allied with the fundamentalists, who want religious views to be reflected in the government’s actions, it has done its best to shed the fundamentalists of any culpability concerning Gandhi’s assassination. By extracting from the public realm facts and opinions that challenge the fundamentalists, the Indian government is using propaganda to influence the public in favor of the fundamentalists.

Such extreme sensitivity to the contents of a documentary film promoting peace is extraordinary, especially since the CBFC has reported plans to permit pornographic movies. This shows that the CBFC is not an inherently strict organization, but that it mandates harsh deletions in order to help the government in political situations.

The Board has been consistently using delay and pressure tactics to block the film from viewing. For example, even though War and Peace was supposed to be a feature film in a film festival organized by the Films Division of India in Kolkata, it was mysteriously withdrawn from the festival. While the CBFC made several excuses, they were unconvincing, especially in view of the prior boast and threat by the regional officer of the Censor Board in Mumbai that he would prevent the screening in Kolkata.

According to a report in The Times of India, Patwardhan might meet with a large committee from the Board in an attempt to resolve the issue. However, Patwardhan notes that the issue extends beyond the banning of his own documentary and has implications for the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression guaranteed by the Indian

Constitution, which states that "officials of the Censor Board must be made to understand that their brief cannot be to wield their scissors in the interest of any particular ideology."

26

Even though the Constitution specifically condemns the Censor Board’s use of propaganda, the CBFC continues to make excuses to support their actions. The Censor

Board’s chairman has stated that certain scenes in the film are objectionable and could incite trouble. In a press release, he said, "I do not want a law and order situation over the film.” Just like in the case of the ban on PTV, the Censor Board made allegations without offering any foundational evidence or analysis.

In fact, the response of viewers in Bangalore suggests that, with its emphasis on peace and non-violence, the documentary is sobering rather than inciting. Thus, the

Censor Board has no reason to believe that this film on peace is as a potential instigator of violence.

Patwardhan upholding the liberty of art at the Centre for Civil Society in New

Delhi, India

The banning of this film also emphasizes the far-reaching effect of the documentary as a tool against propaganda. As independent film-makers in India have

27 access to more technology, they can make better films that allow them to disseminate fresh ideas in the pubic realm. Another film that serves as a good example is the internationally acclaimed film, The Final Solution , which documents the bloody anti-

Muslim riots in 2002 in the Hindu nationalist-ruled state of Gujarat. With a title referring to the Holocaust,

The Final Solution uses interviews and archive footage to recount the grisly violence and continued religious polarization in Gujarat, where 2,000 people died in the riots. These riots broke out after an allegedly Muslim mob torched a train carrying

Hindu activists, killing 59 people. Most of the subsequent victims were Muslim and human rights groups.

Map of Gujarat, where the anti-Muslim riots of

2002 occurred

Rakesh Sharma’s powerful film won two awards at the Berlin International Film

Festival in February, 2004, and has since been screened extensively overseas. In fact,

Sharma toured with the movie across the United States and Canada from mid-September to late October.

Despite its popularity and success, the film has not been shown extensively in

India because, once again, the Censor Board has decided to order a ban. The censor board

28 told Sharma that it would not issue a certificate for public screening of The Final Solution because the film could incite fresh religious tension. The trend is obvious. For movies that ideologically oppose the views of the government, the Censor Board, dominated by allies of India's former Hindu nationalist government that lost power in an election upset in May, conveniently concludes that such movies will “incite violence.”

Luckily, in this case, Sharma has stated that he would fight the ban by distributing thousands of video CDs to be shown in private homes, which are not affected by the

Censor Board. With a greater population of the public owning computers and having access to computers, directors like Sharma can counteract unfair censorship. Advanced technology helps directors battle propaganda, leading to a better marketplace of ideas.

Furthermore, Table 2 (detailing the advancement of ICTs in India) shows a dramatic increase in the number of computers available for educational purposes. From 1995 to

2001, the number of computers in educational settings rose from 23,600 to 238,700! Due to the advancement of computer technology in India, the chances that video CDs will be effectively disseminated are high. Thus, film-makers and the public at large are armed with a new tool against the spread of propaganda.

A still from Sharma’s The Final Solution portraying the anti-Muslim riots in Gujarat

29

Sharma also remarked that he hoped to organize illegal public screenings with prominent directors to "challenge the authorities to come and arrest” them. According to

Sharma, "when we are faced with this kind of action, we have to find innovative methods of civil disobedience.” Furthermore, Sharma said that he would appeal against the ban either through the courts or India's new left-leaning government, which has vowed to speed up prosecution of perpetrators of the Gujarat bloodletting. He has already held up to 100 private screenings of The Final Solution in India without incident, shattering censor board claims that the movie could stir trouble.

Directors like Sharma have hoped to force a debate about censorship in India.

While the advancement of ICTs does empower the pubic against censorship, the banning of films and TV stations nevertheless has a damaging effect on the exchange of information. As Sharma points out, "If Indians have the right to vote and decide who governs them, it is rather silly that they don't have the right to choose what to watch.”

Propaganda Analysis

As suggested before, one solution to the problem of unfair censorship is to force the censor boards of both countries to conduct propaganda analysis before using propaganda as the basis for censoring material. Although Pakistan is ruled by a military dictatorship, India is democratic and thus more likely to accept a rule that mandates propaganda analysis. This will help prevent the Censor Board from using propaganda as an excuse for censoring permissible material.

The two types of analysis suggested earlier were message and content analysis.

30

While message analysis concerns the means by which the content is transmitted to society, content analysis obviously refers to the analysis of the content of the material at question. Propaganda analysis would first require the legislative committee to draft a base case that would be the basis of comparison for what constitutes propaganda. This would be better accomplished through an international committee, probably an organization formed by the United Nations. Putting an international organization in charge of a propaganda analysis committee would ensure that the committee would remain fair and unbiased.

Conclusion

The advancement of communications technology has had a double-edged effect on propaganda in India and Pakistan. The extensive development of the television industry (such as the development of satellite TV) in Pakistan has enabled the government to possess a tighter control over media flow. Because many users no longer use cheap, individual antennas that would be difficult to remove, the government can effectively ban the Indian TV stations that challenge Pakistani “national” ideology. India has similarly banned Pakistan TV for its citizens. However, the increasing availability of computers (more so in India than in Pakistan) allows individuals to use the internet as well as media such as video CDs to watch banned movies and TV shows.

In response to the Indian government’s ban on several films that contest governmental legitimacy, many film-makers and other activists have tried to promote public debate on issues of censorship. Because both the Pakistani and Indian governments have had a record of barring information exchange between each other in

31 times of heightened conflict, both nations require regulation of censorship. An international committee responsible for tracking allegations of improper censorship issues in countries would be ideal. Such an organization would establish subsidiaries in nations notorious for unfair censorship to help maintain a free flow of information.

32

Bibliography http://popups.ctv.ca/content/publish/popups/india_pakistan/frameset.html http://adaniel.tripod.com/princely.htm http://www.cultsock.ndirect.co.uk/MUHome/cshtml/index.html http://serendipity.li/more/propagan.html http://www.instecdigital.com/1/timeline.htm http://www.worldbank.org/data/countrydata/ictglance.htm http://www.ifex.org/en/content/view/full/24666/ http://www.indianexpress.com/ie/daily/19990603/ige03090.html http://www.cpj.org/protests/99ltrs/India4June99.html http://www.internews.org/articles/2004/20040125_nytimes_pakistan.htm http://www.indexonline.org/news/20020704_india.shtml www.nebraskastudies.org/. ../0801_0135.html http://www.jdchandler.com/propaganda.htm news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/ world/south_asia/2743881.stm www.humansecuritybulletin.info/ archive/en_v1i... http://www.rastko.org.yu/kosovo/istorija/ccsavich-propaganda.html#_Toc496330800 http://sify.com/movies/bollywood/fullstory.php?id=13539517 http://www.tribuneindia.com/2004/20040222/spectrum/mif1.jpg&imgrefurl=http://www.

tribuneindia.com/2004/20040222/spectrum/main3.htm&h=289&w=230&sz=20&tbnid=4

9lf2rzqBLYJ:&tbnh=109&tbnw=87&start=9&prev=/images%3Fq%3Danand%2BPatwar dhan%26hl%3Den%26lr%3D%26sa%3DG http://patwardhan.com/writings/press/122603.htm http://www.atimes.com/ind-pak/DA18Df03.html

http://www.cnn.com/WORLD/9708/India97/ http://www.indexonline.org/news/20020704_india.shtml

33