here - MCHIP

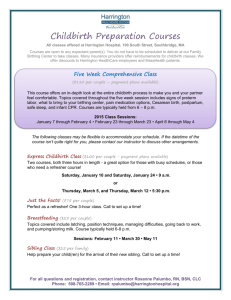

advertisement