Field trip 4 - Washington coast

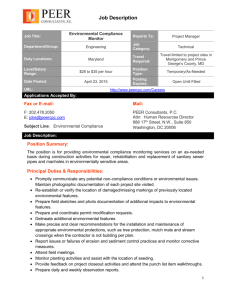

advertisement

Paul McWilliams Ocean/ESS 230 Field Trip #4 Washington Beaches Evidence of tsunamis can be found near the shores of Willapa Bay in southwest Washington State. Exposed strata feature compelling evidence of prehistoric earthquakes and the massive tsunamis that charged ashore as a result. The subduction zone of the Washington coast is an area of frequent and powerful earthquake activity. Evidence of such tsunamis exist in the form of soil and vegetation that were quickly buried and preserved beneath sandy layers of sediment that were deposited within the minutes and hours that followed earthquakes. Further evidence of such earthquakes can be seen where the land had subsided because of an earthquake and as a result the soil and vegetation were buried beneath muddy tidal flats. Beaches exist in dynamic equilibrium. Rather than being stationary, sediment that makes up beaches is in transport and thus sediment that is moved away must be replenished if the beach is to remain stable. Littoral Transport, or longshore drift, is the primary mechanism, a result of wave refraction, which transports sediment along coastlines. Where a break in the shoreline occurs because of flooded river valleys or other natural features, sediment continues to be moved by littoral drift and is deposited in offshore barrier spits. The barriers are normally prevented from entirely cutting off the ocean from the lagoon. The erosive force of flood and ebb tides, that service the lagoon, maintain an inlet to the lagoon behind the barrier. As sediments are moved and deposited at the end of the spit on the up-current side of the inlet, the inlet itself serves as a barrier to the transport of sediment so that the down current side of the inlet is no longer replenished with new sediment supply. Erosion of the beach occurs because littoral transport continues to operate in that area although the sediment supply from up current is cut off, and therefore sediment is carried away without being replenished. Thus, as the up-current spit grows across the inlet the down-current side of the inlet is eroded away and the inlet migrates. At some point the barrier may began to reach the end of the natural feature that created the lagoon, when this happens a new inlet may form farther up-current and the inlets migration begins over again. Jetties, such as those at the mouth of Gray’s Harbor, are manmade engineering structures constructed to stabilize inlets in place. These large structures, on the order of kilometers in length are built of large immobile materials, such as boulders, on the edges of the inlet perpendicular to the shore and parallel to the channel. They work by cutting of the supply of sediment by littoral drift to the inlet. Often they are carefully engineered to restrict the width of an inlet and focus the erosive energy of the tidal interchange in order to maintain the channel. Jetties, however, come with a price. Increased sediment deposition occurs on the up-current side of the jetty system resulting in large, and often problematic accumulations. On the down-current end of the system the supply of sediment has been cut off and even more problematic erosional trends remove large portions of the shoreline. The ocean beaches of the Washington coast from Cape Disappointment, at the mouth of the Columbia River, to Point Grenville are heavily dependent on sandy sediment supplied by the Columbia River. Although sand generally makes up only ten percent of a river’s sediment load, the Columbia River moves a lot of sediment—and ten percent of a lot is a still a lot. Sandy sediments delivered to the mouth of the Columbia are moved northward by the prevailing littoral drift. As the sandy sediment continues to migrate northward, beaches must be continually replenished if they are to remain stable. In the past few decades, erosion has been observed along this part of the Washington coast. It is thought that because much of the sediment traditionally supplied by the Columbia River is now trapped behind Dams. Unlike their neighbors to the south, the beaches north of point Grenville are independent of the Columbia River Littoral system. Instead they are fed by the erosion of cliffs that exist because of the proximity of the Olympic foothills to the coast. The size of the material on the cliff-fed beaches is much larger than that of the sandy river-fed beaches. As a result, the foreshore of the headland beaches near Kalaloch is steeper because the erosion force of backwash is lessened by the fact that the larger grained beach is more porous and allows more water to drain through to the water table instead of washing back over the beach. Much like the Washington shore within the Columbia River Littoral system, Ediz Hook, near Port Angeles, and Dungeness Spit near Sequim are fed and maintained by sediment supplied by rivers and transported by littoral drift. Ediz Hook in particular depends largely on the supply of sediment from the El’wha River. Because the El’wha river has been dammed, and much of the sand sediment is trapped in the reservoir above the dam the supply to Ediz Hook is greatly reduced. Because littoral transport in the Strait of Juan De Fuca continues to move sediment erosion is occurring at Ediz Hook and engineering measures have been required to artificially strengthen this natural feature. Dungeness spit is similarly vulnerable to the reduction in supplied sediment, although the impact may be less pronounced because much of its sediment supply comes from cliff erosion that occurs along the strait to the west of spit. The most obvious solution to this problem, besides continual maintenance of artificial reinforcement to these natural spits, seems to be a removal of the dams on the El’wha River. Doing so would restore the supply of sediment to the spits, but this fix does not come without costs. These costs are not fully understood, but it is known that the sediment currently collected by the dam would be eroded and released and a relatively sudden slug of natural organic pollutants would be quickly released into the river and the Straits of Juan De Fuca. This relatively sudden change in the nature of the river’s sediment load will have great impacts on life in the river and upon sea life in the straight. Oysters and Salmon are among the creatures that will be most affected. While the pollutants that would be released by a removal of the El’wha dams are mostly natural, s similar removal of dams on the Snake and Columbia rivers will be likely to contain heavy industrial contaminants, agricultural byproducts such as pesticides, and even radioisotopes from nuclear power plants. Such releases have great potential to wreak ecological havoc and must be considered with great care.