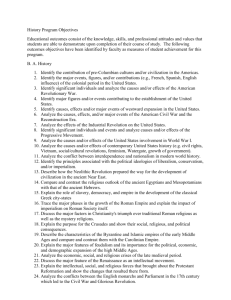

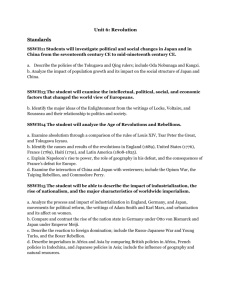

UNIT IV: 1750-1914

advertisement