edwards_syndrome_sp_debate_followup info_490116 (2).

advertisement

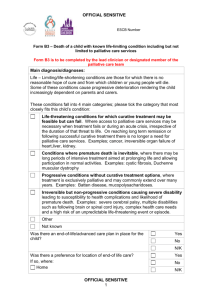

Dear Mary, Many thanks for your enquiry concerning Edward’s syndrome, and the Members debate that took place last month. Ultimately, the delivery of services to babies with Edward’s syndrome and their parents are a matter for each NHS Board. However, I have pulled together a range of information, including some from the debate itself, which details some of the relevant work being undertaken in this area. As you noted in your enquiry, the motion and the subsequent debate (col 14748-14759) included discussion of palliative care services, but it also touched on screening for Edward’s Syndrome during pregnancy and bereavement services, amongst other topics, all of which I will cover below. Edward’s syndrome As noted on the NHS Choices website, Edward's syndrome, also known as trisomy 18, is a genetic condition which disrupts the baby's normal course of development. As regards incidence, I have seen a couple of figures quoted. The NHS Choices website refers to Edward's syndrome affecting around 1 in 3,000-5,000 live births. However, in the debate and on several other websites, I have seen reference to 1 in 6,000 live births. The chance of having a baby with the syndrome increases with age. The majority of foetuses with the syndrome die before birth. Of those that are born, NHS Choices notes that a third of these will die within a month of birth because of life-threatening medical problems. Only 5-10% of babies with full Edward's syndrome survives beyond one year, and will live with severe disabilities. There is no cure for Edward's syndrome and the symptoms can be very difficult to manage. Children with the condition may benefit from physiotherapy and occupational therapy, if limb abnormalities affect their movements. They may also require to be fed through a feeding tube. The NHS Choices webpage provides more information on the condition, its various types and symptoms. Testing for Edward’s syndrome The leaflet on the syndrome produced by the Scottish Genetics Education Network (SGGEN), notes that the syndrome can be detected through an ultrasound scan. It describes the physical abnormalities that can be picked up in the scan that would indicate the foetus has the syndrome. I understand these checks would happen during the ultrasound foetal anomaly scan, which takes place between 18-20 weeks. NHS Choices suggests that this scan can pick up the signs that a baby may have Edward's syndrome in 90% of cases. However, the diagnosis is confirmed using either chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis. These are invasive tests carried out during pregnancy to detect whether the unborn baby could develop, or has developed, an abnormality or serious health condition. In the debate the experience of one couple in particular was described, and how, in their case, Edward’s syndrome was only confirmed at 31 weeks. This was felt to be too late in the pregnancy (col 14749). In responding to the debate, the Minister for Public Health stated: “Through the current antenatal screening programme that is offered to pregnant women, the majority of cases with Edwards’s syndrome will be detected halfway through pregnancy. A number of members have referred to the importance of early diagnosis. It may be helpful if I point out that the United Kingdom National Screening Committee is considering specific screening for Edwards syndrome and Patau syndrome in the first trimester. We expect to receive the conclusions of that work by spring next year; we will then consider how to take that forward as national policy.” (col 14756) Palliative Care Pathway As noted above, those babies born with Edward’s syndrome are likely to have a short life, and in the debate there was much discussion about the care and support needed by the babies and their families. During the debate (e.g. col 14749-14750), reference was made to the development of a care pathway for the delivery of care and support for babies who have life-limiting conditions. This is being undertaken through the Perinatal Palliative Care Framework Managed Clinical Network (South East Scotland). As you will see the draft Framework aims to ensure that there are recognised pathways of palliative care for a baby within and between foetal medicine, maternity, neonatal units and other services for every baby who has a lifelimiting/life-threatening condition. It recommends a range of key goals and standards that should be achieved to deliver care. It also describes key training required and potential process to audit the standards. The Framework takes into account two documents: British Association of Perinatal Medicine (2010) Palliative care (supportive and end-of life care) A Framework for Clinical Practice in Perinatal Medicine ACT (now Together For Short Lives) (2009) A Neonatal Pathway for Babies with Palliative Care Needs During the debate (col 14750) it was noted that this draft Framework had been put out to consultation, with a view to refining it by the end of January 2013. Thereafter, it is hoped that the pathway will be accepted as a pathway across all three managed clinical neonatal networks in Scotland and that it will be presented to the Scottish Children and Young People’s Palliative Care Executive. Other palliative care developments In response to the debate, the Minister for Public Health (col 14757-14758), though not discussing the draft care pathway outlined above, made note of a number of other developments. Neonatal care quality framework In 2010 the Scottish Government set up the Neonatal Expert Advisory Group to devise standards for neonatal services. During the debate, the Minister for Public Health stated: “Through our neonatal quality framework, which will be published soon, neonatal services will be required to provide evidence of person-centred care, including palliative care. Families, including siblings, should be offered access to communication, information and advocacy services, including referrals for counselling and bereavement support. That is intended to support them in their participation around discussions, clinical care decisions, palliative care planning and end-of-life care, if that is required. Such planning should also take account of families’ cultural and religious preferences, needs and values. Palliative care planning and endof-life decisions should be made in partnership with professionals and parents, and care should be provided in an appropriate environment, whether that is a hospice or a home setting.” (col 14757). Framework for palliative care ‘A Framework for the Delivery of Palliative Care for Children and Young People in Scotland’, was developed by the Scottish Children and Young People’s Palliative Care Executive Group and published in November 2012. The Framework aims to ensure that there are recognised pathways for palliative care within and between NHS Boards for every child and young person from the point of diagnosis of a life-limiting condition or life-threatening condition, through to living with their conditions until the end of their life. It contains a number of recommendations, with five overarching objectives: 1. Each Health Board should clearly identify lead professionals with overall responsibility for delivering children and young people’s palliative care services. 2. Children and young people’s palliative care services should be planned and developed on the basis of incidence and prevalence in each Health Board area. 3. All children and young people should have equitable access to palliative care which is flexible, planned and person centred and takes account of their physical, emotional and spiritual needs. 4. All children and young people should be cared for and die in their preferred place. 5. All children and young people with palliative care needs will receive safe, effective and person centred care delivered efficiently and on time by a trained and competent workforce adopting a GIRFEC (Getting it Right for Every Child) approach. In his response to the debate the Minister for Public Health stated that these five objectives had been: “…highlighted to all chief executives of NHS boards in Scotland. In advancing those outcomes, they will deliver the palliative care services that children and young people need. I expect all boards to implement the outcomes as a matter of priority.” (col 14758) MCN for children with exceptional health needs In addition, the Minister for Public Health made reference to the National Managed Clinical Network for Children with Exceptional Healthcare Needs. This was set up in 2009 with the aim of strengthening services for this group. Parents/carers, voluntary sector organisations and professionals are invited to join the network and attend working group meetings and events. There are currently over 1500 people involved in the network. The Minister for Public Health stated that this Network allows the sharing of good practice across Scotland and to agree pathways of care. He felt this should help practitioners to support children with such needs. Bereavement care How bereavement care is delivered is a matter for NHS Boards, but during the debate, there was some mention of the Scottish Government’s guidance ‘Shaping Bereavement Care – A Framework for Action’ (February 2011). This was based on a report from a multi-disciplinary group. It sets out a range of recommendations. During the debate the Minister for Public Health said that the framework: “…sets out a framework of action for boards and recognises the need for better co-ordination and understanding of the needs of people who are bereaved. A national bereavement pack and information leaflet were developed to support health boards in implementing the guidance, and the series of modules that have been rolled out to help to raise awareness and provide further support for staff include a specific module on the death of a child.” (col 14758). Voluntary sector support During debate, two organisations in particular were discussed in relation to support for babies with Edward’s syndrome and their families. The first was Soft UK. This is a UK wide charity which aims to help those with Edward’s syndrome and other related disorders. It contains a range of information that you may find useful. The second was the Children’s Hospice Association Scotland, which is the only charity in the country that provides hospice services for children and young g people. In addition to these, the Together for Short Lives charity contains a range of resources for families and professionals in relation to palliative care for children and young people. I hope this information is useful. Should you require any further information, please do not hesitate to contact me. Regards. Jude Payne Senior Research Specialist – Health and Social Care SPICe Direct Dial Tel: 0131 348 5364 RNID Typetalk 18001 0131 348 5364 Fax: 0131 348 5050 Email: spice@scottish.parliament.uk SPICe enquiry number: 85300