Africa Drought - Desertification

advertisement

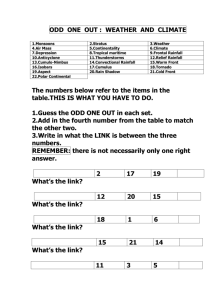

Africa Drought Conor McMenemie. 55D Trent Road. London. SW2 5BJ 078761 87261 mcmenemieconor@hotmail.com. Xan Rice in Nairobi guardian.co.uk, Thursday 3 June 2010 Severe drought causes hunger for 10 million in West Africa Eastern Sahel crisis is worst in Niger where 7.1 million are hungry as livestock and crops are lost and food prices surge A severe drought is causing increasing hunger across the Eastern Sahel in West Africa, affecting 10 million people in four countries, aid agencies warned today. In Niger, the worst-affected country, 7.1 million are hungry, with nearly half considered highly food insecure because of the loss of livestock and crops coupled with a surge in prices. In Chad, 2 million require food aid. The eastern parts of Mali and northern Cameroon have also been badly affected by the failed rains, says the UN World Food Programme, which described the situation as critical. The main cause of the droughts that have affected Sub Saharan Africa over the passed century is changes to the mid summer surface salinity and temperature of the South Eastern Mediterranean Sea, which inturn is directly caused by the construction and operation of the Aswan dams on the River Nile. By understanding the root of this problem it is possible to take measures that can allow for Sub Saharan rainfall to be regulated, thus allowing for a higher decree of stability in the region and for confident investment in the areas agriculture. 1 A drought is when rainfall is significantly less than average for the area, for the time of year; not enough to water all of your plants and livestock. By realising what average rainfall is, one is then able to compare this to actual rainfall (in this study the average figures relate to the years 1945 to 64). Figure 1, which uses such information from 18 measuring sites across a band of Northern Africa, known as the Sahel, over a period of 61 years, shows how this rainfall has varied. Fig 1 Source 1 By using the same method to produce a graph (figure 2) of the variance in water flowing through the Aswan dams on the Nile in Egypt we are able to provide this graph. Fig 2 Source 2 Placing both sets of information on the same graph (figure 3) demonstrates the same trends occur in both the Sahelian Rainfall and the Aswan Runoff. Fig 3 Source 1 & 2 2 An underlying fact that must be fully appreciated when viewing this strong correlation, is that the objective of producing the Aswan dam in the first instance was to deliberately restrict the mid summer flood of the River Nile, thus alterations to the Nile flow from Aswan are to a large extent anthropogenic. For Sahelian rainfall to follow much the same pattern, one would have to examine what mechanisms are involved that can allow for the Aswan operation to cause changes to the Sahelian rainfall. The main changes too the Aswan runoff in this instance being the 1933 enlargement of the original 1902 Dam, followed by the 1964 construction of the Aswan High Dam (AHD). These events changed the nature of the South Eastern Mediterranean (SE Med) Sea Surface by reducing the area of ‘relatively’ warm fresh water that would appear there each summer. By understanding that fresh water floats upon salt water, and that it evaporates quicker (see Evaporation chapter at the end of this paper), altering the Mid Summer Nile flood would ultimately affect the mass of moisture produced in the region at that time. Figure 4 provides us with information that demonstrates the effectiveness of the enlargement of the original dam and the newer Aswan High Dam. Fig 4 Aswan Runoff tons/per second Source 2 3 To provide some useful numbers for the amounts in question one can look to studies compiled by Professor Sharaf at Alexandria University, Egypt. He was able to demonstrate the actual changes to the Mediterranean Sea surface salinity and temperature over the years before (figure 5) and after (figure 6) the commencement of the Aswan High dam. Fig 5 South eastern Mediterranean August to October, surface salinity, pre 1964. Source 3 Fig 6 South eastern Mediterranean August September, surface salinity, anti 1964. Source 3 Prior to 1964, an area in the region of 35,000 square kilometres would appear on the surface of the Mediterranean due to the mid summer Nile flood. This area will be known as ‘Lake Sharaf’. This area had a surface temperature ranging from 26C close to the Nile estuaries, declining to 17C further off shore, with a similar surface salinity gradient ranging from 28% to 39%. Both the surface salinity and surface temperature are factors that affect the level of evaporation of moisture in the area. 4 The Hadley Cell (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hadley_cell) Concurrent with the seasonal appearance of this warm, lower salinity lake is the arrival of a weather system known as the Hadley cell, as shown in Figure 7. Fig 7 As the sun migrates south to north and back again over the year, it provides a body of rising warm air. This rising effect draws air from up to 3,000 km north and south. Moisture in this system rises to about 4,000 meters, condenses into cloud in this colder altitude, then falls as rain, this band of seasonal rainfall is commonly known as the ‘rainy season’, Figure 8. This seasonal migration of the ‘rainy season’ is best understood by looking at the ‘Africa Rain (GIF)’ animation. Fig 8 Source 1 Fig 8 is data taken from NAPD, and demonstrates that the African continent is provided with a distinct and relatively simple seasonal rainfall pattern. That there is a high degree of predictability in both timing and location of peak rainfall. Using this same data field but comparing average rainfall pre/anti AHD, one is able to establish where and when the gross rainfall reduces, thus establish why. 5 From mid June when this system is in the north, it begins to drag moisture from the Mediterranean southward into Sub Saharan Africa, supplementing the late summer rains. But due to this reduction in the mass of moisture that had been produced in the SE Med each year, there is a year on year reduction in the overall ‘rainfall budget’ for the Sahel. Figure 8 shows how the peak rainfall over the African continent migrates with the sun south to north to south over the year. Fig 8A Source 1 Again using information from figure 8, to allow for a better understanding of the how the rain within this migrating Hadley varies with the season and location. This demonstrates that there is a significent increase in the overall rainfall within the African Hadley Cell between June and August (1945-64 mean): 39%, but the increase reduced to an average of 23% for the same months after 1965. Understanding this relationship can allow us to look at specific timesscale and location Figure 8A again forces us to ask why there is this significant increase in rainfall at this location and time? Looking to the vastness of documents and studies relating to how rainfall in this region corelates to features in the Indian/Pacific and Atlantic oceans, one may be inclined to initially go with the prevailing oppinions on the matter; that they are the most significant factors. Conversley the Sahel: southern border of the Sahara, is not world famous for heavy rain, but figure 8 demonstrates that much of the heaviest rains in the continent occur in this region, allbeit confined to a relativley short period. The big question is why there, why mid summer? To find the right answers we must begin to start asking the right questions, and in most respects this paper is to allow us to begin to start asking those right questions. It is just as important to establish why there is the constant reduction in rainfall from March to June, as it is to establish the increase from June to August. So too is it necessary to establish why the largest reduction in 6 In any single year this change in rainfall may account for a degree of inconvenience, but not necessarily sufficient to be called a drought. It is only the compounded effect of this year upon year shortfall does one really begun to appreciate that there is another factor to be considered. Fig 9 Source 1 The blue bars represent rainfall by degrees of latitude prior to 1964; gray denotes the rainfall deficit after 1964. The Sahara contributes no meaningful amounts of moisture to this system. Figure 9 represents of a snapshot (mid August, pre 1964) of the location and relative mass of rainfall over the African continent at any given time (Fig 9. is a reconfiguration of the same data as in figure 8). It demonstrates that the vast majority of rainfall occurs in a relatively narrow band when the Hadley Cell is in the North. The region in the red box denotes in this particular timeframe, an area that receives very little rainfall and virtually no cloud cover, plus is swept by a warm south wind. This means that a vast area of earth and vegetation is wilting and drying up. This drying-up process releases billions of tons of moisture back into the Hadley cell. Thus a significant fraction of rainfall as seen in this chart is actually provided by moisture that had been previously stored in a mobile ‘reservoir’ of ground water and vegetation. Prior to 1964 the Mediterranean moisture contribution had topped up this ground/vegetation reservoir. The 7 droughts as we know them are the effects of this year upon year reduction in the mass of the vegetation reservoir, due to the reduction in the Mediterranean moisture/rainfall contribution. Figure 10 is a very basic summary of the effects, before and after the introduction of dams at Aswan. Fig 10 8 Aswan Dams: design remit The purpose of the original Aswan Dam was specifically to extend and lengthen the growing season of crops in the lower Nile, to allow for cereal crop export to Europe via the Mediterranean, and the East via the Suez Canal, (hydroelectricity was a useful by-product, but not the main goal). By artificially increasing the flow of the river ‘off season’, this theoretically allowed for greater areas of land to be more easily irrigated ~ using the stored water from the previous late summer flood. Unfortunatly as seen in figure 4, although this enterprise had the effect of increasing land utility by reducing the overall scale of the late summer flood, this same anomaly reduced the scope for enlargement of the irrigation scheme; every time part of the late summer flood was retained behind the dam (concurrent with the desired operating remit for the dam), there resulted in a corresponding reduction in the gross Nile flow above the dam. In the long term negating the desired magnitude of the advantages to the irrigation scheme. Enlargement of the dam was seen to be the solution, but then again Nile flow reduced. Conversely, unexpected and sporadic increases in the Nile flood from time to time, put sufficient pressure on the dam structure to destroy it (this dose not just mean the dam falls down; people drown, crops are washed away, starvation, cholera). Ultimately the operators of the dam had to manage a balancing act of trying to ensure the maximum level of water behind the dam, but to ensure that they were in a position to be able to let enough water out to prevent the whole structure being demolished by an unexpected high flood. But by providing such an emergency reduction in the reservoir level to accommodate a coming flood, there was the real danger of destroying both lives and crops down stream. The obvious conclusion was that the original Aswan Dam was not fit for purpose. It was not big enough, nor strong enough to cope with the challenges provided by the Nile; it presented a real and present danger to the majority of the Egyptian population. The Aswan High Dam began construction in the late 1950s and began to affect the Nile flow as of 1964 when the reservoir (Lake Nasser) began to fill too its capacity of 124 cubic kilometres of water. 9 Other possible causes of Sahelian Drought SST forcing and Sahel rainfall variability in simulations of the 20th and 21st Centuries: ‘The outlook for rainfall in the Sahel is very uncertain: we do not know whether we should expect positive or negative rainfall anomalies in the Sahel under global warming’. Source 7 There is a vast army of dedicated, highly inteligent and motivated individuals around the world that are trying to unravel the question of the Sahelian drought. Wikipedia has provided us with some insight into this rainfall anomaly and again highlighted the fact that no solid conclusion has been found. Wikipedia: (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sahel_drought) Potential factors contributing to Sahel drought Originally it was believed that the drought in the Sahel primarily was caused by humans over-using natural resources in the region through overgrazing, deforestation[25] and poor land management.[26] [27] In the late 1990s,[citation needed] climate model studies suggested that large scale climate changes were also triggers for the drought. In the early 2000s, after the phenomenon of global dimming was discovered, some speculatively suggested[citation needed] that the drought was likely caused by air pollution generated in Eurasia and North America. The pollution changed the properties of clouds over the Atlantic Ocean, disturbing the monsoons and shifting the tropical rains southwards. In 2005, a series of climate modeling studies performed at NOAA / Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory indicated that the late 20th century Sahel drought was likely a climatic response to changing sea surface temperature patterns, and that it could be viewed as a combination of natural variability superimposed upon an anthropogenic ally forced regional drying trend.[28] Using GFDL CM2.X, these climate model simulations indicated that the general late 20th century Sahel drying trend was attributable to humaninduced factors; largely due to an increase in greenhouse gases and partly due to an increase in atmospheric aerosols. In IPCC future scenario A2 (CO2 value of ≈860 ppm) Sahel rainfall could be reduced by up to 25% by year 2100, according to climate models. A 2006 study by NOAA scientists Rong Zhang and Thomas L. Delworth suggests that the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation plays a leading role. An AMO warm phase strengthens the summer rainfall over Sahel, while a cold phase reduces it.[29] The AMO entered a warm phase in 1995 and, assuming a 70-year cycle (following peaks in ≈1880 and ≈1950), will peak around 2020.[30] A 2009 study by Shanahan et al. found further evidence for a link between the AMO and West African drought.[31] 10 Chicken and egg? In the arena of climate change it is too often difficult to determine which piece of information is a cause and which is an effect, since changes to one system will have a rippling effect that can alter other systems in remote locations, over an extended time period. Although there is a strong correlation between Sub Saharan rainfall and that of the AMO as mentioned in the text, this chicken and egg question arises. From figure 2 we can be confident that the reduced flow of water in the Nile at Aswan in the five years after 1964 is determined entirely by the filling of Lake Nasser: this is a well documented historical fact. This had an effect upon the evaporation rate of the E Med at the time. A similar event of lesser significance took place after the enlargement of the original dam in 1933. Coinciding with these two events was a steady decline in Sahelian Rainfall. Prior to that there is a dearth of useful rainfall data, thus being able to provide any reliable comparisons before then becomes questionable. What can be introduced into this area is that of Aswan Runoff data from 1870 (GRDC: Aswan), showing gross annual runoff. Figures 11 and 11a are respectively Mean Aswan Runoff, June, July August, September (JJAS) and gross annual runoff. The fact that the gradients remain the same in both instances again presents the same question. If JJAS runoffs are anthropogenic, why has this affected the total for the year? Theoretically off-season runoff from the reservoirs should have compensated for the rainy season reduction, to produce a near constant annual runoff figure throughout the 1870 to 1984 time period. This has not happened. Additionally one can be drawn to the fact that at each up scaling of the dam system, there is a corresponding reduction in runoff. Fig 11 Mean AHD runoff data June, July, August, September, (GRDC), 1870 to 1984. Original Construction Upgrades AHD 11 Fig 11b Annual Aswan runoff data (GRDC), 1870 to 1984. Original Construction Upgrades AHD If we are to understand that Sahelian rainfall is determined by Nile Runoff (as strongly suggested in this study), and that the runoff figure is 52% of what it had been prior to the original 1902 dam construction, we must also extrapolate that rainfall in the Sahel has followed much the same decline. Thus allowing us to better understand Sahelian Rainfall variances, by back dating our mean figures to pre 1902 levels. Evaporation In this kitchen sink experiment involving two glasses that contain water of the same salinity as sea water. Coloured water of the same salinity was added to the glass on the left, fresh water to the glass on the right. To a large extent the fresh water of slightly lower density will float upon the sea water, in effect creating a fresh water lake on the sea. The rate of evaporation of this area of water will vary dependent upon this salinity factor. This experiment helps to demonstrate that the character of the sea surface will alter when fresh water is introduced. 12 An open air salt water/fresh water evaporation study had demonstrated a 3.48% difference in the rates of evaporation per day, (figure 12) but in this case the temperature of both bodies of water were the same. According to Sharaf, the Mediterranean Sea water is 17C and the fresh water from the Nile varies from 26C to 17C. Consequently the evaporation percentage difference should be higher. Fig 12 Source 4 In reality the year on year reduction in Aswan Runoff between 1964 and when the runoff figures regularised in 1969, we can produce an approximate reduction in the surface area of Lake Sharaf: figure 13. Consistent with this we can introduce the factor of evotransportation in the area using the above figure from fig 12, but this only relates to salinity changes, temp/evaporation changes have not been used due to a lack of specific information. Fig 13 Year Area of Lake Sharaf (m2) Year on Year Reduction 1964 35,000,000,000,000 -6% 1965 2,255,210,413,714 -10% 1966 223,063,804,687 -16% 1967 34,609,629,658 -11% 1968 3,808,053,685 -6% 1969 230,631,752 -5% To summarise this study, a single molecule of moisture produced in the Mediterranean mid summer is drawn south into the African Continent, then falls as rain, contributing to ground water and vegetation growth. A few months later the vegetations subsides and the moisture is released to return to the Hadley cell, where it falls as rain, repeating this vegetation cycle. This continues until the moisture flows out of the system in a river, or is blown westward into the Atlantic. Less moisture is produced in the Mediterranean due to a change in its Mid Summer Sea surface salinity. 13 Why is this study so important? Not only does this study allow us to be able to begin to tackle the issues relating to a very large human population over a very significant area of land, it also compels us to look more closely at how dams can affect climate in the context of ‘global climate change’. To highlight this feature it must be appreciated that dam construction falls within the timescales as defined with anthropogenic climate change, and will affect the total solar energy applied to the planet by varying the area of cloud that is available to reflect incoming solar energy back out to space. Given that the sun provides us with 40,000 times more energy than humans produce, even minor variances in cloud cover, particularly at the equator, will affect the mean sea surface temperatures, thus Global Mean Temperatures. Existing sea surface currents transport this temperature change from the equator both north and south. In all respects failing to tackle this issue will ensure that the GMT data remains highly questionable. This can be exemplified by looking at Figure 13, global sea surface temperatures (Met Off) from a solar perspective, using 180’ E as a centre point to the graph rather than 1’E. This allows us to take a better look at the magnitude of an El Nino event. Under ‘normal’ circumstances the prevailing surface currents run north along the western coast of South America (Humboldt Current), then westward through the Pacific. During the El Nino event, this sea surface changes to an eastward flow. BUT El Nino is a statistical anomaly: changes to SSTs are comparative to that of ‘non El Nino’ years: compared to ‘Normal years’. Given that it is established that dams can have a major effect upon seasonal SSTs and SSS, and that there are in the region of 10 such projects in the western Andes, we should be able to appreciate that where the Aswan held back warm fresh water, the Andean dams to the largest extent hold back cold snow melt. That this factor should affect our understanding of what is ‘normal’, for the area covered by El Nino. This being that although the event as shown in this instance is dramatic and sporadic, and we have a natural tendency to be drawn to the unusual; our real area of concern should be that we should also be querying the validity of our ‘normal’ SSTs for the area, since it is them that have most probably been changed anthropogenically. Fig 13 14 By understanding where, why and when these conditions take place, it is possible to examine what remedial actions may be introduced to increase and stabilise the Sub Saharan Rainfall budget. The area and timing in question is specific to that covered by the migration of the Hadley cell; mid June, and anywhere north of the Sahara. Virtually all moisture produced in this region over this time period will produce cloud and rain in the Sahel within two days. Sea water can be brought into the northern Sahara to the Qattara Depression (131 meters below sea level) and the Dead Sea (420 meters below sea level). Both of these endeavours will produce additional moisture in large volume, but a potentially more useful option involves bringing warm fresh water from the mouths of the Nile to both locations. Egypt has demonstrated over a few thousand years that it is not shy of large construction projects. Both of these endeavours should also have the effect of increasing the mass of water flowing into the Nile itself. By introducing such projects it becomes viable to allow for confident large scale capital investment in Sub Saharan agriculture: particularly beef and bio-diesel. This can prove a massive boon to the relevant economies, provided they are nurtured in the early stages, rather than exposed to the ravages of ‘free market economics’. Failure in this respect can relegate the indigenous populations to that which has afflicted much of the native populations of North and South America. Oversight of the whole project would have to include ridged staggered introduction in any enlargement of the agriculture base, both in the factors of location and time. So too would social and political structures have to be put in place to ensure a useful and smooth transition from highly labour intensive agricultural practices, to that of industrialised farming and to protect the rights of those that have lived on the land for many generations. A levy may be placed upon exports to help contribute to the cost of meeting the debt incurred by the original Qattara/Dead Sea projects. If the opinions of the author mean anything in this context, it is strongly suggested that land tenure be based on that of the French Commune system. This allows for commercial farming on a 25 year renewable lease, with rents paid directly to the local council, from which such monies is dispersed to meeting the needs of the local community. Such a provision ensures that much of the wealth remains within the local economy to provide for amenities like education, clean water, sanitation, police, civil administration, pensions, medical facilities and transport, a further portion of said income being passed to regional then central government. C. 15 Sources 1 Nicholson's Africa Precipitation, monthly 1901 - 1984 (ds571.0) "The data for this study are from the Research Data Archive (RDA) which is maintained by the Computational and Information Systems Laboratory (CISL) at the National Centre for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). NCAR is sponsored by the National Science Foundation (NSF). The original data are available from the RDA (http://dss.ucar.edu) in dataset number ds571.0." 2 The Global Runoff Data Centre, 56068 Koblenz, Germany" (GRDC): Aswan 1984 "The data for this study are from the Research Data Archive (RDA) which is maintained by the Computational and Information Systems Laboratory (CISL) at the National Centre for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). NCAR is sponsored by the National Science Foundation (NSF). The original data are available from the RDA (http://dss.ucar.edu) in dataset number ds552.0." 3 Effects of the Aswan High Dam on the estuarine and coastal circulation pattern along the Egyptian Mediterranean coast. S.H. SHARAF AL DIN Oceanography Department, Faculty of Science, Alexandria University, Egypt. Seawater Evaporation Experiments: Determining Relative Evaporation Rates Warren Finley, Wader, LLC, 1076 Skyline Drive, Laguna Beach, CA. 92651 Anthony T. Jones, OceanUS consulting, 22 Battery Street, Ste. 401, San Francisco, CA. 94111 Somalia Climate Graph (metric) Mogadishu http://www.climatetemp.info/somalia/ 10.2.6.3. Climatic Factors in Desertification IPCC Working Group II: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability SST forcing and Sahel rainfall variability in simulations of the 20th and 21st centuries. M. Biasutti 1 I. M. Held 2 A. Giannini 3 A. H. Sobel 4 Columbia University - Oceanography 4 5 6 7 Conor McMenemie © 08 March 2010 55D Trent Road London United Kingdom SW2 5BJ 00 (44) 78761 87261 mcmenemieconor@hotmail.com 16