3. Accounting Templates

advertisement

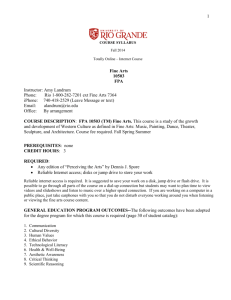

Table of Contents Section Page 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 2. Water Budget Integration: Issues with Approach and Terminology ........................................ 4 2.1 Objectives in Developing Water Budgets ....................................................................... 4 2.1.1 Area .................................................................................................................... 5 2.1.2 Time Period ........................................................................................................ 6 2.1.3 Technical Approach ............................................................................................ 7 2.1.4 Inconsistencies Within Plans ............................................................................... 9 2.2 Recommended Terminology ........................................................................................ 10 3. Accounting Templates ......................................................................................................... 13 3.1 Water Budget Template ............................................................................................... 14 3.2 Implementation Template............................................................................................. 15 3.2.1 Water Conservation Template ........................................................................... 15 3.2.2 Water Supply Template..................................................................................... 16 3.2.3 Compact Compliance Template ........................................................................ 17 4. Summary and Recommendations ....................................................................................... 18 References ............................................................................................................................... 21 D:\533563466.doc i List of Figures Figure 1 The Three Middle Rio Grande Planning Regions and Surface Water Basins List of Tables Table 1 Sources of Information for Water Budgets in the Three Planning Regions 2 Terms for Surface Water Budgets in the Three Planning Regions 3 Water Budget Terms for Estimating Flow in the Rio Grande at Elephant Butte Reservoir 4 Recommended Terminology for Surface Water Budget Terms 5 Recommended Groundwater Budget Terminology 6 Template for Tracking Surface Water Budgets 7 Template for Tracking Groundwater Budgets List of Appendices Appendix A Surface Water Budgets from the Three Planning Regions B Groundwater Budgets from the Three Planning Regions D:\533563466.doc ii 1. Introduction Regional water planning was initiated in New Mexico in 1987, with the purpose of protecting New Mexico water resources while ensuring that each region is prepared to meet future water demands. The state was segregated into 16 planning regions, and each region developed its own regional water plan with some type of oversight committee. Regional water planning activities throughout the State were primarily funded and overseen by the New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission (ISC). In central New Mexico, three of the planning regions—Jemez y Sangre (JyS), the Middle Rio Grande (MRG), and Socorro-Sierra (SS)—all rely for a portion of their supply on the Rio Grande. Use of the water supply along the Rio Grande, including connected groundwater, is limited by the Rio Grande Compact, an agreement among the states of Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas. The Rio Grande Compact defines a schedule of deliveries at Elephant Butte Reservoir based on index flows at the Otowi Gage, which is located in the JyS planning region (Figure 1); the required deliveries at Elephant Butte effectively limit consumptive uses in the area between the Otowi gage and Elephant Butte, known as the Middle Rio Grande Surface Water Basin (MRGWSB). Since the three regions rely at least partially on this one limited water supply, the New Mexico Water Dialogue, a non-profit group devoted to water planning, initiated efforts in 2006 to begin a discussion of the common water supply among the three regions, resulting in the forming of a coalition of representatives from the three regions and from the ISC, informally referred to as the “upstream/downstream group.” This group, with ISC funding and oversight, retained Daniel B. Stephens & Associates, Inc. and Amy C. Lewis to integrate the water budgets laid out in the three regional water plans. Key objectives in evaluating a shared supply for the water planning regions between Otowi and Elephant Butte, as defined in the scope of work, are to: Define common terms and methodology so that the regional water plans can be compared in a manner that accurately reflects the technical situation. D:\533563466.doc 1 Provide a brief summary of methodology and assumptions that each region used to assess its water supply and demand. Describe a process and methodology toward standardization of the data, assumptions, and methodology in the three plans, including establishing items to be included in a water budget, such as categories of supply and use. Without revising estimates of projected supply or demand based on new information, integrate the data from the three plans, using assumptions as are reasonable and necessary, and assess the common supply in relation to current and proposed demands to understand whether the supply is adequate to address demand. Identify and understand conflicts between the plans (i.e., if each planning region is intending to meet its future demands with the same source of supply, a conflict exists that needs to be resolved). Develop an accounting template to be used as a tool to measure the effectiveness of actions taken to balance the water budget at the regional and basin levels. This interim report summarizes the first two tasks and the last task of this scope of work. While the three water budgets were integrated, the approach needs to be vetted with the original authors and conflicts in interpretations resolved before finalizing the integrated budget. This initial effort also indicated the need for better development of the goals and objectives before proceeding with the integration of the water budgets and development of the templates. The limited time and budget available for the first phase of this project did not allow for the review and revisions necessary to do so. Each of the planning regions faces a wide variety of issues, some of which are pertinent to issues regarding groundwater that is not connected to the Rio Grande or tributaries distant from the Rio Grande. For this analysis, however, the focus of the review of the water budget terms is for the MRGSWB, which includes the Rio Grande and its tributaries between the Otowi gage and Elephant Butte Reservoir and stream-connected groundwater (Figure 1). D:\533563466.doc 2 A detailed study of the MRGSWB was funded by the ISC and the COE (S.S. Papadopulos & Associates, Inc. [SSPA], 2004). The 4-year study involved probabilistic modeling of the inflow and outflow terms for the MRGSWB water supply to evaluate the likelihood of being in compliance with the Rio Grande Compact. The work included in the scope of this evaluation was not intended to replace or critique the much more detailed earlier work of the MRGSWB study, as detailed in the Middle Rio Grande Water Supply Study report (SSPA, 2004). However, the integration of the water budgets involved using the SSPA study as a suggested approach and recommending modifications. D:\533563466.doc 3 2. Water Budget Integration: Issues with Approach and Terminology Review of the water budgets revealed several issues that need to be resolved before integrating the water budgets. To move forward with integration of the water budgets, the objectives and goals for developing the budgets need to be consistent and the terminology and definitions of water budget components need to be compatible. The tables in Appendix A show the water budget components for the tributaries and the mainstem as detailed in each of the three region’s water plans. Appendix B is a compilation of the groundwater budget information available in each regional plan. Water budgets for the three plans were obtained from the reports listed in Table 1. Table 2 details the differences in each of the water budget components, as compiled in Appendices A and B; the specific inconsistencies and incompatibilities are discussed in Sections 2.1 and 2.2. 2.1 Objectives in Developing Water Budgets Each of the three regions had different approaches to developing the water plans, which resulted in conflicts when integrating the various components. The conflicts develop where (1) the areal extent is not coincident with the MRGSWB, (2) the time period evaluated is different among the regions, and (3) the technical approach to and/or assumptions made in developing the budget varies. Some of the differences in the water budgets evolved because the issues within each region are different or the available data are different: In the JyS region, the critical water budget components are the flows in the tributaries and groundwater; the source of supply for the portion of the JyS region that is within the MRGSWB is not the Rio Grande (although some new supply directly from the Rio Grande is expected to begin to be used in the next few years). Therefore, the supply and demand numbers involved diversions from Rio Grande tributaries and from groundwater. Water budgets were prepared for both surface water (from the tributaries) and groundwater for each subregion within the JyS region, but no water budget was developed for the Rio Grande, because the flow into the Rio Grande, while estimated, was not critical to answering water supply questions in the JyS region. D:\533563466.doc 4 The MRG water budgets have focused only on the Rio Grande. While demands on the Rios Jemez and Puerco (tributaries to the Rio Grande) were estimated in a subregional plan (Hebard and Johnson, 2004) appended to the MRG water plan, the water budget components (such as inflow and seepage losses) were not estimated. Although recharge to groundwater basins in the SS region was estimated, the SS regional water budgets also focused primarily on the Rio Grande, which supplies the majority of the water demands in the region through the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District (MRGCD). The fact that some of the plans only addressed impacts to the Rio Grande and others addressed demands on tributaries is one of the most difficult aspects of integrating the water plans between regions, because not all of the demands have an impact on the flows of the Rio Grande originating at Otowi. In moving forward with the integration, the upstream/downstream group will need to agree on a methodology for considering demands (such as diversions from the Santa Fe River by the City of Santa Fe) that don’t impact the main stem. For instance, should the supply component of the water budgets include flows originating at the mountain front, or should demands that do not have a direct impact on the Rio Grande be excluded? While it may be simpler to address only the flows on the Rio Grande, it becomes complicated to compare supply against demand and assess a possible deficit when some of the demands are met through supply that doesn’t directly impact the Rio Grande. 2.1.1 Area Several inconsistencies exist regarding the area considered for the water budgets in the three plans: As shown in Figure 1, the JyS region extends above the Otowi gage into the Upper Rio Grande Basin. The SS region includes portions below Elephant Butte Reservoir in the Lower Rio Grande Basin. D:\533563466.doc 5 The water budgets developed by SSPA (2004) for the MRG planning region used data from a groundwater model of the MRG groundwater basin that did not include the reach from Otowi to Cochiti; thus their surface water model lacked detail from Otowi to Cochiti. For the Santa Fe-Los Alamos area, SSPA (2004) relied on the New Mexico Office of the State Engineer (OSE) administrative groundwater model (McAda and Wasiolek, 1988) for the impact on the Rio Grande caused by pumping the Buckman well field; however, part of those impacts occur above the Otowi gage, so not all of this should be included in the MRG reach. The SSPA (2004) water budget did not include open water and riparian evapotranspiration between Otowi and Cochiti. Tributary flow from Rio Puerco enters the SS region, but was also included in the MRG plan. Accordingly, the upstream/downstream group needs to decide what areal extent should be covered in the integration of the plans. 2.1.2 Time Period The period of record used to establish a mean or median value of streamflow or diversion will impact the value of a water budget component. For example, both the MRG and JyS regions included the Santa Fe River in the water budgets, as an inflow in the former and as an outflow in the latter. However, the MRG assumes a much higher number for inflow from the Santa Fe River into the Rio Grande than the JyS estimated outflow. For the MRG, SSPA (2004) based the Santa Fe River flow of 9,580 ac-ft/yr on the relatively short period of record from 1993 to 1998 at the La Bajada gage; conversely, the JyS region estimated only 1,110 ac-ft/yr based on the long-term water budget of the Santa Fe River (1913 through 1997). A decision should always be made regarding the appropriate time period for the water budget analysis. Unfortunately, consistent periods of record are not always available. D:\533563466.doc 6 2.1.3 Technical Approach Several different approaches among the plans resulted in inconsistencies, as outlined in the following subsections. 2.1.3.1 Santa Fe River Assumptions In addition to the different time periods used by the MRG and JyS regions for the Santa Fe River water budget estimates (Section 2.1.2), other assumptions were also different. While the MRG region assumed that the Santa Fe River contributes significant inflow into the Rio Grande, the JyS region estimated that the Santa Fe River loses flow to groundwater between the La Bajada gage and the Rio Grande because the flow in the Santa Fe River rarely makes it into Cochiti Reservoir. Because the JyS region was focused on the components of the groundwater budget, this loss became a recharge component in the groundwater budgets. Even though such losses likely reappear as spring flow issuing to the Rio Grande, they would need to be tracked as spring/stream gain rather than tributary flow. 2.1.3.2 Agricultural Demand SSPA’s (2003, 2004) method of estimating agricultural demand in the MRG and SS regions differed from the technique used by the JyS region. SSPA’s methodology introduced a water budget term called “effective precipitation” that is not included in the JyS water budgets, and SSPA only estimated irrigation depletions, whereas JyS showed both diversions and return flows. For the MRG and SS regions, SSPA estimated the total consumption by crops using a 1992 GIS coverage of irrigated acreage and potential evapotranspiration rates from 1975 to 2002. The estimate also included the amount of water that crops consume from precipitation, (i.e., effective precipitation), which was added to the inflow components. Effective precipitation was estimated to be 50 percent of the average annual rainfall (8.52 inches) at the Albuquerque WSFA Airport meteorological station from 1950 to 2002. SSPA’s methodology also did not include the amount of incidental depletions that occur with irrigation (such as open-water evaporation and evapotranspiration along canals). These were included as separate water D:\533563466.doc 7 budget terms (open-water and riparian evapotranspiration for both agricultural- and nonagricultural-related depletions). In contrast, the JyS region based its irrigation demand on estimates of diversions and return flow. The irrigation depletion estimates (necessary to estimate return flow) included the consumptive irrigation requirement and incidental depletions of the diverted water only; the amount of precipitation consumed by the crops was not part of the water budgets. While no water is diverted from the Rio Grande below Otowi, the JyS region did estimate the amount of water diverted from tributaries (namely, the Santa Fe River and the Galisteo River) for irrigation using OSE’s estimates for 1995 (Wilson and Lucero, 1997), which are based on crop areas and ditch efficiencies. To fully integrate the budgets, the upstream/downstream group will need to agree on the approach to developing the water demand components, that is, should all components of irrigation (diversions, depletions, return flows) be included in the water budgets? 2.1.3.3 Stream Gain/Loss The Rio Grande is generally considered a gaining stream and certainly was so prior to development of connected groundwater resources. A model developed by McAda and Barroll (2002) estimated the predevelopment total gain to the Rio Grande within the MRG to be 49,940 ac-ft/yr. SSPA estimated that 16,500 ac-ft/yr of groundwater fed the Rio Grande within the SS region above Elephant Butte based on Roybal (1981). The JyS region estimated inflow of 10,670 ac-ft/yr based on groundwater level contours (Duke, 2001) and flow net analysis. SSPA added a term to the water budgets to account for the impact of groundwater pumping in the JyS, MRG, and SS regions on the flow in the Rio Grande as estimated by the McAda and Barroll model (2002). The details of these estimates should be examined and made consistent with the predevelopment gains for all reaches of the Rio Grande. For instance, SSPA includes impacts from pumping at the Buckman wells, but does not include the predevelopment gain within this reach, nor does it include the impacts of pumping from Los Alamos wells. Because impacts of pumping do not necessarily draw water directly from the river, but may instead intercept water D:\533563466.doc 8 that would have flowed to the river, it is important to include the predevelopment stream gains if the groundwater impacts are to be included in the budget. In the SS region, only the pumping from the City of Socorro and New Mexico Tech was included (3,300 ac-ft/yr) and the impact of that pumping was considered to be 100 percent. However, according to Wilson et al. (2003), the total pumping in the SS region from all demands is closer to 44,000 ac-ft/yr, including more than 36,000 ac-ft/yr from irrigation wells. While the impact from the irrigation wells is included in the irrigation depletion component, the 8,000 ac-ft/yr of pumping from other uses (including the 3,300 ac-ft/yr from the City of Socorro and New Mexico Tech) is not fully considered, and the impact from pumping may therefore be underestimated. 2.1.4 Inconsistencies Within Plans Some additional inconsistencies between estimates within individual water plans (e.g., between estimates of demand and water budget components) were noted: Demand projections for the SS plan relied on OSE-estimated year 2000 demands (Wilson et al., 2003) and then projected changes to 2040. However, the year 2000 demands are not consistent with the demand estimates used in the water budget. For instance, the irrigation depletions in the SS plan water budget (as extracted from SSPA, 2003) were estimated at 48,500 ac-ft/yr when accounting for effective precipitation (Section 2.1.3.2) (55,360 ac-ft/yr minus 6,820 ac-ft/yr). However, the demand projections in the SS plan show irrigation depletions of 77,600 ac-ft/yr. This discrepancy occurred because the demand projections, including agricultural use, were developed prior to and independently of the SSPA model and were based on OSE's water use report (Wilson et al., 2003). Based on the OSE 2000 water use report (Wilson et al., 2003), the portion of irrigation depletions in Socorro and Sierra Counties that lie within the MRG are about 82 percent of the total county depletions, or about 64,000 ac-ft/yr, about 30 percent more than the amount shown by SSPA for the water budgets. D:\533563466.doc 9 In the MRG, SSPA (2004) simulated the impacts on the Rio Grande from historical pumping of 150,474 acre-feet in 2000. However, the demand projections in the water plan show pumping of 163,450 acre-feet in 2000. To fully integrate the budgets, the upstream/downstream group will need to agree on an approach to make the projections consistent with the demand numbers in the water budgets. 2.2 Recommended Terminology Review of the water budgets revealed the need for consistent terminology when developing and discussing water budgets. Two terms that often cause confusion are “deficit” and “supplydemand gap.” The term deficit could refer to many different aspects of a water budget. For instance, it could refer to a shortfall in meeting a Compact obligation, or the amount of water currently depleted that exceeds recharge, or the difference between demand in a wet year and supply in a dry year. Clear adjectives, such as “Compact deficit” or “groundwater budget deficit,” are necessary when using this term. The supply-demand gap term used in the JyS region refers to the gap between the supply available to meet current demands (as of 2000) and the projected demand in 2060, which could also be considered a “deficit” between supply and demand in the year 2060. The potentially diminishing supplies are not factored into the supply-demand gap as defined here. Supplies that may diminish even if demand does not increase (such as surface supplies impacted by climate change or groundwater supplies that diminish from over-pumping, thus creating another type of supply-demand gap) should be assessed separately. Each region will have different issues with regard to deficits and gaps, and the scope and definition of each term should be clearly stated. Such terms may not be transferable between all regions. For the water budget integration, the following definitions are proposed (and should be discussed by the upstream/downstream group): D:\533563466.doc 10 Modeled compact deficit: Simulated deficit in meeting the median compact delivery obligation Annual (or actual) compact deficit: Difference between actual deliveries and the delivery obligation in a particular year. Groundwater budget deficit: Difference between the amount of recharge and the amount of pumping minus return flow to the aquifer. Supply-demand gap: Difference between the amount of water supply available to meet demand at the time of the study (which is for the plans in question, the year 2000) and the future water demand for a given year (e.g., 2040). The demand is expressed in terms of diversions, but can also be expressed in terms of depletions and called a supply-demand depletion gap. In some cases the supply-demand gap can simply be calculated by subtracting the current demand from the future demand. However, if a region has more supply available than is required to meet current demands, then the supply available should be subtracted from the future demand to estimate the supplydemand gap. To improve consistency among the water budgets tracked by the three regions, definitions of other water budget terms should also be standardized. For example, a definition of riparian evapotranspiration should be agreed upon and clearly stated. One issue regarding this term is whether it should include acreage of riparian vegetation that occurs along irrigation canals, or whether that should (or can) be tracked separately. The answer could be yes or no depending on the situation. If the canals are located in the floodplain, the riparian losses may have occurred even if the canals were not present. On the other hand, if a canal traverses along a hill slope, the “riparian losses,” if defined only to be riparian vegetation such as cottonwoods, may need to be applied to incidental depletions associated with irrigation. An alternative method to define riparian acreage could be the depth to groundwater. The various entities that are involved in water budget tracking should agree upon the appropriate terminology and definitions. Tables 3 and 4 summarize generic surface water and D:\533563466.doc 11 groundwater budget components that are applicable to any water plan and provide suggested definitions of the terms. Table 5 explains each of the water budget terms that are recommended to be included in a water budget that is focused on the flow in the Rio Grande only. D:\533563466.doc 12 3. Accounting Templates The scope of work developed for this project specified the development of a standard method of tracking changes in water supply and demand in the region that could help decision makers understand progress made or additional problems arising regarding the water balance in the MRGSWB. Ongoing tracking of the water supply and demand terms would be helpful to: The planning entities, in incorporating new data to help refine the understanding and reduce uncertainty regarding Rio Grande water budgets Communities within the region, in assessing changes they have made to increase their supplies or to reduce their demands through conservation The agricultural sector, in understanding how they can make better use of the available water Municipalities that face increasing demands The State of New Mexico, to better understand depletions and assess future Compact compliance status There are several different mechanisms that may be appropriate for tracking changes in water supply, demand, and associated gaps: A water budget template could be used to track inflows to and diversions from the Rio Grande based on measured data for the time period of interest and to reflect updates to estimated parameters (such as groundwater inflow or riparian evapotranspiration based on new scientific studies) A general tracking template could be used to assess progress on implementing the various alternatives or strategies that were outlined in each of the regional plans and to determine the impact that implementation of these strategies has on the water supply D:\533563466.doc 13 and demand balance in the region. In order to quantify the relative impact of various strategies, supporting templates could be used to track Water conservation initiatives Water supply development projects A summary and examples of these types of templates are provided in Sections 3.1 and 3.2. 3.1 Water Budget Template A water budget template should track all components of both groundwater and surface water. The diversions and return flows should be specified, and the proximity to the mainstem of a tributary should be clearly stated. Table 6 is an example template for tracking the surface water budgets in each region. The terms shown on Table 6 can be used to track changes in the water budgets over time, using updated information from scientific studies or actual measured data to refine the understanding of the water budgets. Appendix A provides a compilation of the water budget terms from the three regions using this template. Groundwater budgets should clearly define the inflow and outflow components in specified subbasins within the regions, ideally as they relate to tributaries of a mainstem. Table 7 provides a proposed groundwater budget template; this proposed template was used in compiling the groundwater budget components shown in Appendix B (Table B-1). The water budget template should clearly summarize all of the depletions to the Rio Grande (including evapotranspiration) and allow for comparison of the depletion “pie” from one year another. The total supply can then be compared to depletions and projected depletions. This template could be used both to track the depletions in comparison to the supply and to track potential compact compliance problems. D:\533563466.doc 14 3.2 Implementation Template The purpose of the implementation template is to assess the progress of the alternatives or strategies identified in the water plan and to determine how effective those strategies have been in reducing demand or increasing supply. The JyS region recently completed a draft update of their regional water plan that included a survey of local governments regarding progress or changes in water issues. In many cases the individual water providers are pursuing actions on their own and are not necessarily in communication with the regional water planning groups. Nonetheless, the actions implemented do have an impact on the regional supply, and it is therefore valuable to periodically track the cumulative actions within the water planning or larger region (in the case of this group, the region would be the MRGSWB between Otowi Gage and Elephant Butte). A decision analysis tool, such as the one developed for the MRG region by Sandia National Laboratories (http://uttoncenter.unm.edu/pdfs/Tidwell-2002.pdf) using Powersim, may be the most appropriate method to track the impact or proposed impact of actions taken to address water supply and demand issues. The model has the ability to quantitatively evaluate the consequences of water management actions, such as indoor water conservation (low flow toilets, efficient washing machines, etc), on such outcomes as the flow in the Rio Grande or groundwater depletion. In addition, Sandia and the Upper Rio Grande Water Operations Model (URGWOM) Team are currently collaborating on a monthly time step decision support model in the MRG that supports and is calibrated to URGWOM results. The upstream/downstream group should communicate with the URGWOM Team to understand the refinements underway and how the URGWOM tools might be helpful to the MRG water budget integration process. 3.2.1 Water Conservation Template One of the most viable and effective methods of balancing demand and supply is to reduce demand through water conservation. The effectiveness of conservation in changing demand should be tracked to allow updating of the water budgets based on revised demand. D:\533563466.doc 15 Agricultural conservation can be an effective mechanism for improving crop yield through better water management or for improving deliveries where system losses are significant. However, in many cases conservation measures may result in additional water being applied more efficiently, resulting in improvements in crop yields but not necessarily in water savings. Consequently, the potential for agricultural water conservation should be evaluated on a caseby-case basis and is not included as part of this evaluation. It is recommended that tracking of water conservation be focused instead on the public water supply sector. In order to track water savings or potential increases in water demands, it is important to track both the per capita uses as well as the total population served by the system, to see if the conservation gains have been offset by the addition of new customers, or other potential demands could be filled with the savings. The population estimate at a given time should be compared to the corresponding projection in the water plan to determine if the population projections are still on target. Once the population estimates are evaluated and, if necessary, revised, they can be linked with a conservation tracking template to develop revised water demand projections. The OSE Water Use and Conservation Bureau has been actively involved in developing standardized accounting procedures for tracking water demand. Use of the OSE templates would not only standardize accounting between the three regions, but also would make the plans consistent with water use around the state. 3.2.2 Water Supply Template To understand changes in the water supply-demand balance also requires tracking changes to water supply. Specific methods of calculating how much water would be derived from a given water supply project vary depending on the nature of the project, and it is therefore difficult develop a simple estimate for calculations. Regardless, entities that are undertaking water supply projects generally conduct their own engineering and feasibility studies, and therefore the planning regions do not need to do complex calculations. A simple method of tracking supply is to track the following information on each project: D:\533563466.doc 16 Responsible party Nature of new supply (brackish water, imported water, transfer) Are water rights secured? (Projects that don’t result in water rights, such as phreatophyte removal, cannot be used to address the M&I gap.) Expected completion date Expected amount of new supply Will the supply be reliable during drought conditions? Water quality concerns Where will the new water supply be used? 3.2.3 Compact Compliance Template A Rio Grande Compact compliance template could begin by tracking required deliveries against actual deliveries (information that is already tracked and reported by ISC). This information could be used to chart years when deficits in Compact deliveries occur and those when New Mexico accrues credits, thus allowing for an ongoing quick visual presentation of Compact delivery compliance. Using information from the other templates, as well as updated information on all water use sectors, including riparian evapotranspiration, open water evapotranspiration, and agricultural water use, estimates of the total depletions in the MRGSWB could be tracked and compared to the Compact-allowable depletions based on the delivery schedule. This type of accounting would involve tracking the total consumptive uses in the MRGSWB from the Rio Grande and connected groundwater between Otowi and Elephant Butte. Depletions resulting from other water sources, such as importation of San Juan-Chama water or desalinated water, would be excluded. D:\533563466.doc 17 4. Summary and Recommendations To integrate the water budgets in the regional water plans, each plan needs to follow consistent terminology and methodology, have boundaries that are coincident with hydrologic boundaries, and have the same time frame. Having said that, in many cases, the water budgets will need to be developed from the data available, which may not allow for consistent methodology or time frames. The data limitations and other constraints, such as differing goals, make integration of water budgets and water planning difficult. Recommendations for either retrofitting existing water plans into a standard template or developing new water budgets are provided. However, prior to conducting further analysis to integrate the plans, it is important to revisit the overall goal of doing so. Is the goal to monitor potential changes in flow in the Rio Grande for meeting Compact obligations? Is it to examine the potential impact on agriculture in the region? To answer the former question, the water budget components must be well understood; to answer the later, water budgets are not needed. Some of the data in the plans have changed and hence it may be more beneficial to use current data for any further reconciliation or updates, rather than devoting more effort to working with the plans in the current versions. Key conclusions and recommendations regarding the water budgets are: Decide on the scope of the water budgets, that is, whether they should address impacts to the Rio Grande only or include the demands and supply on the tributaries? If only the Rio Grande is considered, then the demands that are met from supplies on the tributaries should be removed (a problematic approach for the JyS region, where demands are met by a mix of tributary and direct diversions). The surface water budget template should separate tributary water budgets and mainstem water budgets. Groundwater budgets should be developed separately, ideally based on the geographic area of the tributaries to a mainstem or the boundaries of a closed basin. If the budgets are developed in this manner, they can be aggregated as D:\533563466.doc 18 needed to answer specific questions. Appendix A shows the water budgets disaggregated in this manner using the information available. The terminology, methodology, and time frame should be clearly defined in each plan. The terminology should be based on that proposed in Tables 4 and 5; however, the time frame and methodology may vary based on the information available to characterize the water budgets. In addition, decisions regarding issues such as those discussed in Section 2 need to be made to make the water budgets consistent, for instance, whether all components of irrigation (diversions, depletions, return flows) will be included in the water budgets or just the depletion amount. The projections of water demand need to be made consistent with the demand numbers in the water budgets. As stated in Section 1, a detailed hydrologic model is a better method of understanding hydrologic water balances than simple spreadsheet calculations. Whereas a spreadsheet analysis can only track the components for one time period and for the system as a whole, a groundwater model can track changes with time and assess local conditions. For instance, the water budget of the Santa Fe River appears to have more inflow than outflow, yet the aquifer levels are declining around the well fields. The fact that the return flow is occurring far down gradient of the well pumping will not be revealed by a spreadsheet analysis. The upstream/downstream group should communicate with the URGWOM Team to understand the refinements underway and how their tools might be helpful to the MRG water budget integration process, particularly in filling the gaps in groundwater inflow in the reach from Otowi to Cochiti. The systems dynamics model for the MRG Basin, a decision analysis tool developed by Sandia National Laboratories for the MRG could be reviewed and expanded to include information for the three regions and assess the impacts of the alternatives currently D:\533563466.doc 19 being pursued. This tool would be a working model, constantly updated as new information (including groundwater modeling results) becomes available. As the planning regions within the MRGSWB continue to refine their planning goals, appropriate decisions regarding updating and standardizing the integrated water budget can be made. D:\533563466.doc 20 References Daniel B. Stephens & Associates, Inc. (DBS&A) 2003. Socorro-Sierra regional water plan. Prepared for Socorro Soil and Water Conservation District, Socorro, New Mexico. December 2003. DBS&A and Lewis, A. 2003. Jemez y Sangre regional water plan. Prepared for Jemez y Sangre Water Planning Council. March 2003. DBS&A and Lewis, A. 2007. Draft Jemez y Sangre regional water plan 2007 update. Prepared for Jemez y Sangre Water Planning Council. June 30, 2007. Duke Engineering & Services (Duke). 2001. Water supply study, Jemez y Sangre Water Planning Region, New Mexico. Prepared for the Jemez y Sangre Water Planning Council. January 2001. Hebard, E.M. and J.A. Johnson. 2004. Río Puerco & Río Jemez subregional water plan: 20002050. Chapter 12 of the Middle Rio Grande regional water plan. Prepared for Río Puerco y Río Jemez Water Users. April 2004. Hydrosphere Resource Consultants (HRC). 2000. Historic and current water demand in the Socorro-Sierra water planning region. HRC. 2001. Water budget for the Socorro-Sierra water planning region. McAda, D. and P. Barroll. 2002. Simulation of ground-water flow in the Middle Rio Grande Basin between Cochiti and San Acacia, New Mexico. USGS Water Resources Investigations Report 02-4200. McAda, D.P. and M. Wasiolek. 1988. Simulation of the regional geohydrology of the Tesuque aquifer system near Santa Fe, New Mexico. Water-Resources Investigations Report D:\533563466.doc 21 87-4056, U.S. Geological Survey, Albuquerque, New Mexico, prepared in cooperation with the New Mexico State Engineer Office and the Santa Fe Metropolitan Water Board. Roybal, F.E. 1991. Ground-water resources of Socorro, New Mexico. U.S. Geological Survey Water-Resources Investigation Report 89-4083. S.S. Papadopulos & Associates, Inc. (SSPA). 2000. Middle Rio Grande water supply study. Prepared for U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Albuquerque District, and New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission. August 4, 2000. SSPA. 2002. Socorro-Sierra planning region water planning study: Groundwater resources in the Rio Grande and La Jencia basins. Prepared for New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission. July 2002. SSPA. 2003. Middle Rio Grande water supply study, Phase 3: Interim partial draft. August 6, 2003. SSPA. 2004. Middle Rio Grande water supply study, Phase 3. Prepared for U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Albuquerque District, and New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission. November 24, 2004. SSPA. 2006. Middle Rio Grande water budget: Present and projected. October 2006. Water Assembly (WA). 1999. Middle Rio Grande water budget (Where water comes from, & goes, & how much): Averages for 1972-1997. Action Committee. October 1999. Water Assembly (WA) and Mid-Region Council of Governments (MRCOG). 2004. Middle Rio Grande regional water plan, 2000-2050. August 2004. Wilson, B. and A.A. Lucero. 1997. Water use by categories in New Mexico counties and river basins, and irrigated acreage in 1995. New Mexico Office of the State Engineer Technical Report 49. D:\533563466.doc 22 Wilson, B., A.A. Lucero, J.T. Romero, and P.J. Romero. 2003. Water use by categories in New Mexico counties and river basins, and irrigated acreage in 2000. New Mexico Office of the State Engineer Technical Report 51. D:\533563466.doc 23