American Psychological Association 5th Edition

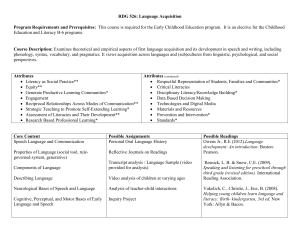

advertisement