Experts: Some wildfire policies put residents at risk

advertisement

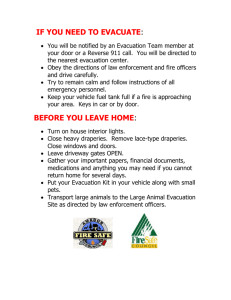

Experts: Some wildfire policies put residents at risk Wildfire managers agree that the approach to residents' safety is chaotic. Australia has a successful plan that may serve as a new model. Evacuation has been synonymous with confusion in many Idaho communities this wildfire season, and that could prove deadly, fire experts say. In recent years, last minute evacuations have been fatal for residents in Southern California and defending evacuated homes has proven deadly for firefighters. In Idaho in 2000, two people using a bulldozer to cut a line ahead of a wildfire south of Salmon were overrun by flames and nearly killed when winds suddenly shifted. This year, several Idaho communities were put under evacuation orders. Here, as in the rest of the U.S., as fires close in on communities, residents are often left to flee down smoky, traffic-clogged roads or stay to defend their homes without proper training, two fire experts said. "This isn't just dumb, it's murderous," said Roger Kennedy, the former National Park Service director and author of the book "Wildfire and Americans." This summer in Idaho, the governor has issued mandatory evacuation orders at least twice as flames and smoke approached communities, but no one has been forced to leave. Local authorities requested the governor's order, but kept it in their back pockets without forcibly removing anyone. Fire has swept through some emptied towns but never reached others where residents were told they were in imminent danger. MIXED SIGNALS Evacuations have been a theme this summer in Idaho as wildfires have swept across the state, charring nearly 2 million acres and destroying about two dozen homes. In what is typical across the country, when a fire nears an Idaho community, the local sheriff, in consultation with fire officials, tells residents when they should leave. The orders have been driven by communications problems, with confused residents complaining that they get different information from the Forest Service, the local sheriff's office and fire officials. For more than a week in August, the mountain town of Yellow Pine was under a "mandatory evacuation" issued by Gov. Butch Otter. Residents were initially told they would be forced to leave, but a sheriff's deputy told them it was up to them. Many stayed and those who left faced a smoky drive with near zero visibility on the road and a threat of falling rocks and trees from the surrounding fire. Yellow Pine General Store Manager Susan Matlock resisted at first but eventually left, which disrupted her life and kept her from her job. The fire still hasn't reached Yellow Pine, and the evacuation order was downgraded, but Monday was reinstated at the "mandatory" level. Last week Matlock said she wouldn't trust such orders. "I will use my own judgment," she said. In the remote river community of Mackay Bar, in the midst of Idaho's rugged Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness, residents stayed and took up hoses to battle the flames when a firestorm came roaring toward them in late July. Three cabins burned, but the residents saved most of the town, including the Mackay Bar Lodge, the linchpin of business for the Salmon River outpost. U.S. wildfire managers and experts agree the way this country approaches the safety of residents in fire-threatened communities is chaotic and sometimes deadly, and they point to a country halfway around the world that has a better approach. ‘Houses save people, people save houses.' The scene is reminiscent of a long-standing program in Australia, a country with parched, scrubby landscapes where fire behavior mimics that of much of the American West. The Bushfire Cooperative Research Center, based in the state of Victoria, has been a leader in Australia's "stay and defend or leave early" approach. Australian fire managers go to wildfire-prone communities and teach homeowners how to develop a family plan to safely leave on a high-fire danger day and how to protect themselves if they choose to stay, Bushfire Cooperative CEO Gary Morgan said. There are no evacuations because each homeowner decides for himself. "Houses save people, people save houses," Morgan said, quoting a motto that encourages able-bodied residents to stay and protect their homes in the face of fires. Unlike in the U.S., Australians who decide to leave are encouraged to go before the fire starts — when weather forecasters issue fire weather warnings — avoiding the sort of last-minute rush that proved deadly when five people were killed while fleeing the 2003 Cedar Fire in Southern California. The training on how to safely defend your house helps avoid injuries like those suffered by the Salmon couple burned in 2000 while trying to defend their property. Morgan credits the program with the fact that there hasn't been a civilian wildfire death in Australia in 10 years. "This also makes people think, ‘Should I really be living in this environment?'" Morgan said. "If you're going to live in that kind of environment, you have to be aware that there's going to be some inconvenience." ‘THE FOLKS IN THE WHITE HATS' Bodie Shaw, a fire preparedness expert with the Boise-based National Interagency Fire Center, spent a month with fire managers in Australia this year and said it's time for the U.S. to discuss a change in fire policy. Shaw said with more people moving into what's known as the wildland-urban interface in fire-prone forest and rangelands in Idaho and across the West, homeowners should take more responsibility for their own protection. "For so many years, firefighters have been the folks in the white hats to come and save the day," he said. Shaw lauds the Australian effort and residents' willingness to shoulder fire-protection responsibility, though he said liability could be a stumbling block to shifting home protection duties from fire crews to homeowners. "They've really taken it upon themselves as their civic responsibility," he said. Shaw points to the national Firewise Communities program, a national, multi-agency effort to protect people, property and natural resources from the risk of wildland fire before a fire starts. Firewise has made strides in getting homeowners to take steps to make their homes less fire-prone, though that program focuses on work homeowners can do prior to fire season rather than defense and safe evacuation procedures. Shaw said the assumption by many homeowners that the federal government is responsible for fire protection may be one reason the U.S. hasn't adopted the Australian model. But that assumption is based in part on reality. In Idaho and elsewhere in the country, firefighters work hard to save structures, including installing sprinklers and wrapping building in fire retardant material. South Lake Tahoe is one fire-prone community that has made fire education a priority for its citizens. When the Angora Fire roared toward the California resort town in late June, many residents had already learned how to devise a family plan to escape fire, said El Dorado County Sheriff's Lt. Marty Hackett, who oversaw the town's evacuation. The fast-moving wildfire torched about 250 homes, but no one was seriously injured. Hackett said the safe evacuation of the town is in part due to classes that teach people to take care of themselves and figure out escape routes ahead of time. "If you feel you're in danger, don't wait for us to tell you you're in danger," he said. One leading critic of U.S. fire policy took it a step further, saying the deadliest time in a fire is during an evacuation, where smoke obscures visibility, nerves are frayed, and people panic. Stephen Pyne, a fire historian and former wildland firefighter, said the battlefield mentality of firefighting in the U.S. wrongly precludes people staying to protect their property. He doesn't blame fire incident commanders, but the accepted idea is that firefighters, not homeowners, should defend houses. "Why are we all considered helpless?" he said. Kennedy, the former National Park Service director, said with so much building in the wildland-urban interface, it's imperative that people moving into fire-prone areas know the risks. "The fire crews are racing the construction crews," he said. Matlock, the Yellow Pine resident, said after all of the miscommunications this summer, she would welcome a program like the one in Australia that puts the decision-making in her hands. "Because of all the mistrust, I'll rely on myself," she said. Heath Druzin: 373-6617