Pay as You Go: Instead of buying computers, you pay for the work

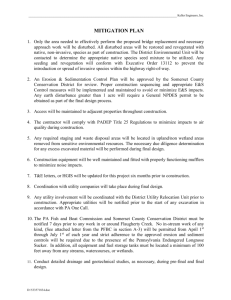

advertisement

Pay as You Go: Instead of buying computers, you pay for the work you do on them; It's a whole new business model -- and it has some big backers Gary McWilliams Mar 31, 2003 THERE'S AN IDEA sweeping through the computer world -- one that has companies rethinking how they buy digital gear and manufacturers rethinking how they sell it. The idea -- called "utility computing" -- involves paying a company to provide you with computing power when you need it. So, instead of buying hardware and software, companies would pay for the work delivered on those systems, much like paying for electricity rather than constructing a power plant. Early adopters of utility computing have been cash-strapped companies that can't afford to buy the latest gear. But the idea is catching on fast among thriving companies that simply want to save money on overhead costs. And many in the computer industry predict such arrangements will boom in years to come as companies face ever-increasing pressure to rein in spending and streamline their operations. "At the end of the day, it's about savings," says Michael Sztejnberg, a managing director in J.P. Morgan Chase's Enterprise Technology Services group, which recently agreed to pay International Business Machines Corp. $5 billion over seven years for utility-computing services. IBM will take over the operation of J.P Morgan's data centers, help desks and network servers, providing extra capacity if needed. The biggest savings with utility computing, Mr. Sztejnberg says, come from better use of computing resources. Today, he says, big corporations overbuy equipment, stocking up on thousands of computers, storage systems and networks that are chronically underused. "There can be multiple servers for each application [that a corporation uses] -- one for production, one for backup and one for testing," he says. "There is limited sharing and very low utilization on average." Meanwhile, for a computer industry struggling with an uncertain future, utility computing could represent a sea change in how technology consumers and their hard-pressed suppliers operate. Instead of selling a computer, a onetime transaction, companies would earn monthly fees for the metered use of a computer. The same goes for software companies: They're accustomed to selling a program and perhaps getting small maintenance fees or an upgrade fee when a customer accepts a new version. Under a utility model, they'd earn revenue based on how much a customer uses their package. Utility-computing advocates are betting that the idea will become so popular that customers will end up buying more services over time, thus making up for the lost equipment sales. Providing everything a customer needs to deliver a paycheck or some other business staple "is a good business for us, and a decent margin business," says Nick van der Zweep, Hewlett-Packard Co.'s director of utility computing. H-P, for instance, offers traditional computer leases as well as utility arrangements. So, a customer could choose between paying $5,000 a month to lease a supercomputer, or take a capacity-on-demand contract and get the same computer as a service for $3,000 to $5,500 a month based on usage. "We guarantee they're not going to pay more than a lease and most likely they'll pay less," says Mr. van der Zweep. "We've shipped over 10,000 of these capacity-on-demand systems." The system works like this. First, you contract with a technology company to provide some or all of the computer infrastructure you need for your business. For example, if you need a top-to-bottom computer setup, the contractor would provide an array of desktop PCs and the network hardware needed to run them. If you just need extra computing capacity during peak times, you might simply get access to the contractor's servers when necessary. After the equipment is set up, you pay the contractor based on how much you use the equipment -- either by the hour or in terms of the number of specific tasks done. So, instead of laying out for a companywide computer network or a massive supercomputer, you might simply pay a monthly bill for each payroll check or health-care claim processed on the system, or each e-mail sent and received. Currently, very little of computer and software companies' revenue comes from utility operations. But the companies are beginning to make big investments in the hardware and software that make utility operations work. IBM Chief Executive Samuel J. Palmisano last October pledged to invest $10 billion over the next five years in research and development, acquisitions and marketing for its e-business on demand utility. H-P and Sun Microsystems Inc. each are rolling out software and services to deliver this new paradigm. Last month, Microsoft Corp. acquired technology from Connectix Corp., San Mateo, Calif., to help network servers handle utility arrangements. Software maker Cisco Systems Inc., of San Jose, Calif., has agreed to make its products fit into H-P and Sun's utility-computing plans. Companies such as Opsware Inc., of Sunnyvale, Calif., already provide software for monitoring, metering and allocating computing costs among departments in a company. So far, many of the firms that have gone the utility route couldn't afford to buy machines of their own. For instance, IBM's earliest customers for its utility services include Amtrak, the troubled railroad, and Petroleum Geo-Services AS, a debt-laden oil-field-services concern based in Oslo. PGS pays for time on an IBM supercomputer to run a three-month-long seismic-processing project. Previously, PGS would have had to expand its data center to handle the peak load. With IBM's supercomputing-on-demand service, PGS simply turned on the faucet for the additional processing power, saving an estimated $1.5 million. "PGS has been looking for a more flexible business model which addresses peak computing requirements . . . but minimizes long-term, incremental cost commitments," said Chris Usher, president of PGS Data Processing. Now utility computing is starting to spread to big, stable companies that simply want to save money -- a category that's growing fast in this unsteady economy. To be sure, the companies are starting slow, combining utility computing with traditional outsourcing deals (which generally offer a fixed price and a fixed set of features, with little wiggle room if your needs change). But utility advocates argue that even those first steps show there's a market for the cutting-edge idea -- and that it will spread as the economics of it become wider known. GATX Capital, a unit of Chicago-based finance company GATX Corp., pays H-P a monthly bill to manage its data center, but can buy more computing power to accommodate its changing needs. IBM, meanwhile, counts among its clients auto-parts maker Visteon Corp. The company was spun off from Ford Motor Co. in 2000, and didn't have its own computer gear. So it signed a 10-year, $2 billion contract to have IBM provide all its systems and ongoing operation service. Visteon will also pay a variable monthly fee depending on how many services it uses. Some industry experts, however, question just how widespread utility computing will be. META Group analyst Dean Davison says that companies won't switch to the utility model unless it's obviously cost-effective -- and companies won't be able to judge that unless they know their own computing habits in great detail. For example, a company would have to know how many e-mails it sent or how many claims it processed in a given month. Many companies don't have the time or resources to track that kind of minutiae. "Companies will have to get away from the idea of how business is done today," he says. "This isn't going to be for everybody." Moreover, Mr. Davison says, companies will need much more detailed information about the quality of service that utility firms provide. Anybody can find out the specs for a specific piece of hardware, he argues, but nobody knows how good a hardware maker will be at providing reliable service. Meanwhile, Randall D. Mott, Dell Computer Corp.'s chief information officer, says utility computing is nothing but an attempt by makers of mainframes and other expensive computers to hold onto their hardware business in the face of lower-cost products -- like the kind Dell makes. Utility advocate Tom Kucharvy, president of Summit Strategies, a Bostonbased technology-consulting firm, believes that argument is a canard. The companies providing utility computing will be always looking to new technologies to lower operating costs, he argues, if only to improve profits. Further, Mr. Kucharvy believes utility computing will spread. The appeal of paying only for what you use, he says, could an irresistible lure as resourcesharing technology becomes more widely available. Indeed, says Mr. Sztejnberg, as companies begin to better grasp the cost of conducting an inventory check or a online sale, the benefits of paying for computing according to the ebb and flow business will become indisputable. "It's not that someone blows a whistle and it all changes," he says. "It'll be a gradual change." --Mr. McWilliams is a staff reporter in The Wall Street Journal's Houston bureau. He can be reached at gary.mcwilliams@wsj.com.