Purpose of Study:

advertisement

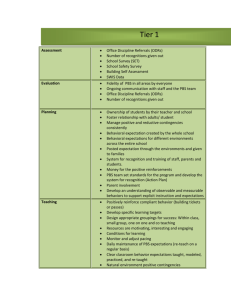

1 Center of Applied Research for Non-Profit Organizations Tulsa Public Schools Office of Special Education and Student Services Positive Behavior Supports Impact of PBS May 2008 Prepared by Heather E. Blagg, B.A. Chan M. Hellman, Ph.D. Mary Guilfoyle-Holmes, MLIS Technical Report No: ARC-053 2 Tulsa Public Schools Positive Behavior Supports (PBS) Executive Summary Positive Behavior Supports (PBS) originated as a set of interventions and systems used to promote positive behavior in students with significant disabilities when exhibiting harmful or disruptive behavior (Sugai, et al., 2000). Under the 1997 amendments made to the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA), it became federal law that when a student’s behavior disrupts learning, PBS strategies should be considered as part of the student’s intervention plan (Sugai, et al., 2000; Wilcox, Turnbull III & Turnbull, 2000). Success with PBS at the individual level have led schools to employ PBS and positive behavior intervention and supports (PBIS) at the school-wide level to foster environments in which children with and without high-risk behavioral tendencies are included (Eber, Sugai, Smith & Scott, 2002). With the popularity of school-wide PBS, the School-Wide Evaluation Tool (SET) was developed to assess fidelity of implementation in primary prevention features in participating schools (Sugai et al., 2001; Horner et al., 2004; Freeman, et al., 2006). The Tulsa Public Schools Office of Special Education and Student Services initiated PBS to combat serious behavior problems in certain school sites in the district. Purpose of Study The Tulsa Public Schools (TPS) Office of Special Education and Student Services sought an external evaluation of the Positive Behavior Supports (PBS) program at several campuses in the district. PBS is designed to create a school-wide climate conducive to students’ academic and behavioral success. This study examines the impact of PBS implementation on suspensions for all students as well as for the special education population and for the population receiving school-based mental health intervention services. This study primarily examines the three-year period from 2004-2005, before any site began implementation of PBS, to 2006-2007. The Office of Special Education and Student Services presented several study questions to the University of Oklahoma-Tulsa Center of Applied Research for Non-Profit Organizations. Does discipline data (namely suspension data) differ among PBS and non-PBS sites? Does greater implementation time, or greater implementation fidelity, appear to change discipline data at PBS sites? Are there differences between the general population and students in special education at PBS schools and at non-PBS schools? For schools and students with mental health/therapeutic intervention services, does discipline data differ? Are changes consistent across elementary, middle and high school levels? Is there an apparent financial impact from the implementation of PBS? 3 The underlying question is apparent. Does PBS help schools? The analysis of data provided by TPS indicates that implementation of PBS at any school level is visibly impactful. This study primarily examines the first two groups of implementers (Cohorts 1 and 2) compared to non-PBS sites. PBS was initiated at sites that had dramatically higher-than-average suspension rates. Sites enter the program voluntarily, and have the option to exit the program voluntarily. The TPS Office of Special Education and Student Services believes that this independence helps a school’s level of “buy-in.” Buy-in is critical to effective implementation of school-wide PBS (Handler, Rey, Connell, Their, Feinberg & Putnam, 2007; Muscott, Mann, Benjamin, Gately, Bell & Muscott, 2004). The implementation of school-wide PBS in Cohorts 1 & 2 appears to have made significant gains bringing these TPS schools closer to (and in some cases better than) the district average with respect to discipline. Cohort 1 reduced average cases of suspension per special education student to only 0.42 cases per student after just 2 years of implementation. Non-PBS high schools and middle schools averaged 0.51 cases per special education student. Cohort 2 decreased total cases of suspension by 22.74% after just one year of implementation. This Cohort 2 decrease saved TPS an estimated $58,163.76 After 2 years of implementation Cohort 1 decreased cases of suspension by 47.92%. Cohort 1 reduced low-level (level 1&2) suspensions 75.75% The average length of suspensions for PBS elementary schools in 2006-2007 was 2.02 days, compared to non-PBS elementary schools average 3.13 days. PBS elementary schools saved an average of $16.32 per case of suspension compared to non-PBS elementary schools. At some TPS sites students with severe behavior problems are enrolled in therapeutic mental health interventions provided by one of four contracting agencies. For students enrolled in mental health intervention services, enrollment in a PBS school appeared to increase average improvement in Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale score by about four times the improvement for students enrolled in mental health services at non-PBS sites. For students enrolled in mental health interventions, students enrolled in a PBS school were suspended an average of 9.87 fewer days than students enrolled in mental health interventions at non-PBS schools in 2006-2007. This group of students at PBS schools received almost two weeks of additional instructional days each than the group at non-PBS schools. This is significant, considering that the Office of Accountability reports that TPS has a 4-year dropout rate more than twice the state average. In the annual evaluation (School-wide Evaluation Tool, or SET), both Cohort 1 sites achieved “high implementation” status after just two years of implementation. Three sites in Cohort 2 achieved high implementation status after just one year (a remarkable achievement). Primary school-wide PBS implementation in Cohort 1 was designed to manage common area procedures and low-level behavioral problems. While success in these areas is noteworthy, Cohort 1 still recorded an increase in high-level suspension cases. PBS teams should build on the successful foundations developed to address severe behaviors. 4 Full Report Method TPS provided suspension, referral, absence and demographic data from the district databases. Individual-level, de-identified data from the district’s mental health interventions program was also supplied. Supplemental information was gathered from the state Office of Accountability. Unless otherwise noted, all TPS and PBS data was provided by TPS as unpublished raw data, (Moore & Snow, 2008). Site evaluations were performed using an instrument adapted from the Sugai, LewisPalmer, Todd and Horner Schoolwide Evaluation Tool version 2.0 (SET) (Sugai, LewisPalmer, Todd & Horner, 2001). The SET was developed at middle and elementary schools to measure implementation of school-wide PBS practices in order to better determine the link between school-wide PBS implementation and desirable outcomes in behavior and academic success. The SET measures primary PBS implementation- not secondary or tertiary systems. Twenty-seven of twenty-eight SET items were highly correlated in developmental research. The remaining item assesses the presence of a crisis plan (a legal requirement), (Horner, Todd, Lewis-Palmer, Irvin, Sugai & Boland, 2004). Tulsa Public Schools adapted the SET to reflect district-specific implementation goals (called the TPS-SET). The item assessing a school’s crisis plan was adapted to measure how well teachers knew the district-wide plan. Other items were tailored to more specifically address goals set by the district PBS teams. Although adaptations are consistent with the original SET instrument, adaptation prevents the TPS-SET from relying completely on validity and reliability testing performed for the original SET instrument (Horner, Todd, Lewis-Palmer, Irvin, Sugai & Boland, 2004). Analysis of the TPS-SET instrument was performed to assess the adaptations. Sub-score and final score item correlations were satisfactorily similar to the original SET instrument (Appendix 1). To conduct the TPS-SET one researcher visited each site to interview fifteen staff members and fifteen students per site. Staff and students were selected randomly from available classes. Walk-through observations were also recorded. Site visits were unannounced. TPS-SET information regarding each site’s PBS team was gathered from site team leaders and district leadership. Principals and PBS team members were surveyed by email and by electronic survey. Referral data at PBS school sites was entered into EducatorsHandbook.com (an online data system). Site summaries of de-identified data were provided by TPS. Before the 2007-2008 academic year there was inconsistent referral tracking, preventing year-toyear comparisons. The research procedure was evaluated and approved by the University of Oklahoma Human Subjects Review Board to ensure ethical treatment of participants. The OU-Tulsa 5 Center of Applied Research for Non-Profit Organizations examined only de-identified and anonymous data. Sample School sites implementing PBS are broken into three cohort groups according to year of implementation. Some sites attempted implementation unsuccessfully in one year and entered the next year’s cohort for re-implementation. For all cases, schools are included in the cohort in which they participated during the 2007-2008 school year regardless of any previous (or future) cohort identification. See table 1 for cohort assignments at the time of study. All district schools were invited to attend a PBS orientation. Schools voluntarily enter (or exit) the PBS program on a site-by-site basis. Table 1. Cohort Assignments at the Time of Study Cohort 1 Cohort 2 (implemented 2005-2006) (implemented 2006-2007) Rogers High School Cleveland Middle School Nimitz Middle School Clinton Middle School Gilcrease Middle School Hamilton Middle School Madison Middle School Bryant Elementary Cooper Elementary Eugene Field Elementary Houston Elementary Marshall Elementary McClure Elementary McKinley Elementary Cohort 3 (implemented 2007-2008) Addams Elementary Burroughs Elementary Celia Clinton Elementary Columbus Elementary Emerson Elementary Grissom Elementary Park Elementary Remington Elementary Robertson Elementary Central High School Before PBS implementation Cohort 1 represented 13.25% of cases of suspension in the district, but only 3.95% of the district population for 2004-2005. Before Cohort 2 implementation these twelve sites represented 22.11% of suspension cases and 12.08% of the population in 2005-2006. (Before Cohort 3 implementation these sites represented 5.41% of district suspension cases and 10.34% of district population for the 2006-2007 academic year. Cohort 3 began implementation in 2007-2008, outside the period of this study. For the purposes of this study Cohort 3 sites are considered in district figures, or “non-PBS” site figures, unless otherwise noted.) The Oklahoma Office of Accountability reports that for 2006 TPS experienced a fouryear dropout rate more than twice the state average (28.9% in the district compared to 14.1% in the state). Among enrolled students 79.6% qualified for free or reduced lunch (Office of Accountability, n.d.). TPS calculated an average daily attendance (ADA) of 38,903.31 for the 2006-2007 academic year. Districts receive funding according to the ADA. Many variables affect the dollar amount for different classes and categories of 6 students, but an average amount per ADA day was calculated by TPS. (20042005≈$12.12; 2005-2006≈$14.58; 2006-2007≈$14.70; 2007-2008≈$16.86). For the purposes of this study alternative schools and charter schools are excluded from district summaries unless otherwise indicated. The 2006-2007 district enrollment population, excluding alternative and charter sites, is 39,636. This population remains fairly stable across the period studied. Results TPS-SET Of the 14 sites evaluated, five met the pre-determined score goal of 80% for fidelity. These are considered “high implementation” sites. Six sites fell between 60% and 80%, and 3 sites scored below 60%. These evaluations provide qualitative as well as quantitative data describing site-specific implementation features. TPS-SET scores were compiled by interviews with district PBS leadership, surveys of PBS team members, surveys of administrators, a walk-through observation of the school site, and interviews with random staff and students. Three Cohort 2 administrators failed to submit the administrator survey. Two schools also submitted zero responses to the team member survey. Another school submitted only one response. All other schools had an adequate response rate. Schools with low responses limit the evaluation process. Table 2 shows sites with their respective TPS-SET scores. Table 2. TPS School-wide Evaluation, 2008 High Implementation Low Implementation Nimitz M.S. (83.10%) Rogers H.S. (84.58%) Clinton M.S. (84.88%) Marshall Elem. (85.71%) Cooper Elem. (91.07%) Very Low Implementation Bryant E.S. (63.33%) Gilcrease M.S. (28.04%) Cleveland M.S. (65.12%) Hamilton M.S. (35.65%) McClure Elem. (66.90%) Madison M.S. (42.14%) Houston Elem. (69.76%) Eugene Field Elem. (73.21%) McKinley Elem. (78.93%) Three schools (Rogers, Nimitz, and Hamilton) had site evaluations in 2007. The instruments employed were not identical. However the same basic areas of implementation were measured according to the same standards adapted from the Sugai, Lewis-Palmer, Todd & Horner SET instrument (2001). Rogers scored 72%, Nimitz scored 69%, and Hamilton scored 67% (all considered low implementation). Several adaptations were designed to better measure TPS-specific implementation goals. One item scored on the TPS-SET (item D2) records and measures the kinds of offenses that staff would refer to the office. This item was adapted from the original SET question “do 90% of staff asked agree with administration on what problems are office-managed and what problems are classroom-managed?” (Sugai, Lewis-Palmer, Todd & Horner, 2001). TPS adapted this item to better quantify this implementation area. A goal of PBS 7 in this district is to manage in the classroom most offenses of the district suspension matrix level 1&2. At each school the 15 randomly surveyed staff were asked “what are three student problems that you consider severe enough to refer to the office?”. Responses were coded according to the suspension matrix (0 points for a non-suspension offense, 1.5 points for level 1&2, 3 points for level 3, and so on…). The average level of staff responses was generated. For example, three very common responses were fighting, disrespect and profanity. Fighting is level 3, but disrespect and profanity are level 1&2. The average level of those three responses is 2.0. Responses within one standard deviation of the mean were assigned one point on item D2. Responses above were given 2 points and responses below were given 0 points for item D2. Simplified, scores greater than or equal to 2.0 were assigned 1 point and scores greater than or equal to 2.75 were given 2 points. District PBS leadership determined that these score values were useful standardizations for future year evaluations. Using the standard deviation to determine the scoring delineations presents one noteworthy limitation. This would become the only item scored that reflected the school site’s position in reference to other school sites. However because the levels determined corresponded with PBS implementation goals, these values were selected as standards for scoring. Appendix 1 shows correlations among subscores and the weighted (final) score. This analysis suggests that TPS adaptations remain essentially consistent with the original SET instrument. A key feature of PBS implementation measured in site evaluations is the school’s “Guidelines for Success,” or mantra. PBS sites are tasked with developing five or fewer positively worded guidelines. Two examples from TPS are “Safe, Civil & Productive” and “Succeed, Organize, Achieve, Respect.” Schools are scored for how well the guidelines conform to the design specifications (five or fewer, positively worded), how frequently they are posted in classrooms and common areas, and how well students and staff know the guidelines by memory (items B4 for students and B5 for staff). Each of these items is strongly correlated to a school’s overall implementation score (item B4 r=0.700, p<0.01; item B5 r=0.723, p<0.01). This suggests that the degree to which staff and students are familiar with the Guidelines for Success is indicative of overall PBS implementation. Suspension Overall the TPS district recorded a decrease in cases of suspension over the three-year period studied. Cohort 1 and Cohort 2 schools represented a disproportionately high rate of suspensions before PBS implementation. Cases of suspension, cases per student, length of suspensions (or days lost to suspension), level of offense, and changes over time were examined at PBS sites and on the district level for all students as well as for the students in special education. Population and demographic data were also compared to suspension data. Schools receive funding according to Average Daily Attendance (ADA) figure, which is reduced when students are out of school for suspension. The financial impact of suspensions at PBS sites and in the rest of the district is examined. TPS employs a seven-level suspension matrix. Offenses are categorized as level 1&2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 or 8. (The combination of 1&2 reduces the formerly eight-level matrix to seven 8 levels.) Low-level offenses (refusing to work, wireless device use, profanity) were targeted by PBS planning personnel to be managed in the classroom, rather than with referrals or suspensions. (For Cohort 1 PBS site plans, high-level offenses are targeted in future years of implementation.) Average suspension levels were calculated by weighting each suspension case according to its level. (Due to the combination of level 1&2, offenses on that level were weighted as 1.5.) PBS leadership believes that suspensions may be underreported in some TPS school sites. This would lead to skewed averagesnamely deflated figures in suspension cases. PBS has been implemented at campuses of all levels (elementary, middle, and high school). In TPS, elementary schools consistently have fewer suspensions (especially high-level suspensions) than middle and high schools. Middle schools generally have somewhat fewer suspensions than high schools, although the differences are not as significant. These considerations are important when examining PBS data. At the time of study Cohort 1 includes one middle school and one high school. Cohort 2 includes seven elementary schools and five middle schools, while Cohort 3 includes ten elementary schools and one high school. Consequently per-student averages for Cohort 1 are expected to be somewhat higher than Cohort 2 or 3 averages due to the presence of elementary schools in Cohorts 2 and 3. Cases of suspension. Cohort 1 demonstrated significant improvement in cases of suspension and in special education suspensions across the three-year period studied. In the pre-implementation year 2004-2005, Cohort 1 represented 3.74% of the district population but accounted for 13.25% of district suspensions. However if elementary schools are removed from the figures, Cohort 1 represented 15.51% of suspensions in TPS middle and high schools, but only 8.77% of that population. In both views Cohort 1 suspensions were disproportionately high. For students in special education Cohort 1 represented only 6.23% of the population before implementation, but represented 13.50% of special education cases of suspension. Cohort 2 implemented PBS in 2006-2007. In the pre-implementation year 2005-2006, Cohort 2 represented 12.08% of the population and 20.45% of suspension cases. For students in special education Cohort 2 represented 15.20% of the population and 23.37% of suspension cases. Both Cohort 1 and 2 improved cases of suspension after implementing PBS. Decreases in cases of suspension for both Cohort 1 and 2 are reflected in the population in special education and in the whole-school population. District-wide the population in special education has diminished slightly, which may have resulted in a natural decrease in cases of suspension. This is evident in non-PBS sites (figure 1). Some decrease district-wide may also be due to efforts by the Office of Special Education and Student Services to provide improved Individual Education Plan (IEP) implementation at all campuses. For cases of suspension per special education student, Cohort 1 still remains slightly above the non-PBS district average. This may be 9 attributed to the fact that there are no elementary schools in Cohort 1, but elementary students account for 48.75% of the special education students in non-PBS sites. When elementary school students are removed from figures, non-PBS middle and high schools have a higher rate of suspension per student in special education than Cohort 1. Because the population changes slowly across the three-year period studied, the significant value is the ratio of cases per student. Figure 1 shows the progress of non-PBS sites. The decrease in cases is similar to the decrease in population. Figure 2 shows these figures for non-PBS middle and high schools. Figure 3 demonstrates the improvement made by Cohort 1. Figure 1. Cases of Suspension in Non-PBS Special Education Students Non-PBS Decrease in Cases, Decrease in Population 6 Thousands 5 4 3 Non-PBS Population Non-PBS Cases 2 1 0 2004-2005 2005-2006 2006-2007 0.53 cases/student 0.51 cases/student 0.30 cases/student 10 Figure 2. Cases of Suspension per Student in Non-PBS Middle and High Schools Non-PBS Decreases in Middle and High Schools 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 Middle and High School Population Middle and High School Cases 500 0 2004-2005 0.80 cases/student 2005-2006 2006-2007 0.82 cases/student 0.51 cases/student Figure 3. Cases of Suspension in Cohort 1 Special Education Students Cohort 1 Decrease in Cases, Decrease in Population 600 500 400 300 200 Cohort 1 Population Cohort 1 cases 100 0 2004-2005 2005-2006 2006-2007 1.35 cases/student 1.03 cases/student 0.42 cases/student 11 The success represented in figure 3 is the rate of reduction. Not only did the Cohort 1 middle and high school have fewer special education suspension cases per student than non-PBS middle and high schools, but they made a 68.89% reduction with just 2 years of implementation. By achieving this reduction, Cohort 1 has achieved greater IEP implementation. With only one year of implementation, Cohort 2 also reduced this figure from 0.89 cases per student before implementation to 0.47 in the first year of PBS implementation (20062007). Table 3 depicts cases per student at the school-wide level and for students in special education. The rate of change in both groups is greatest in Cohort 1. Cohort 2 also changed demonstrated change much greater than non-PBS sites. Table 3. Cases per Student Cohort 1 School-Wide Student Body 2004-2005 1.03 2005-2006 0.82 2006-2007 0.56 change -0.47 Students in Special Education 2004-2005 1.35 2005-2006 1.03 2006-2007 0.42 change -0.93 Cohort 2 Non-PBS sites 0.51 0.52 0.38 -0.13 0.24 0.23 0.20 -0.04 0.88 0.89 0.47 -0.41 0.53 0.51 0.30 -0.23 Both Cohorts 1 and 2 achieved a greater reduction than non-PBS sites. It is important to note that there was no Cohort 2 PBS activity until 2006-2007, which is illustrated in the changes in Table 3. Cohort 2 cases per student were almost unchanged between 20042005 and 2005-2006 for school-wide and special education students. Only after implementation did the values decrease. For Cohort 1 values decrease steadily in both years of implementation. Suspension cases by race. The Tulsa Public Schools district is more ethnically diverse than the state as a whole, and has a higher rate of low income students (according to eligibility for free/reduced lunch), (Office of Accountability, n.d.). Table 4 shows the 2006 district and state populations broken down into five race categories, and estimated free/reduced lunch percentage according to the Office of Accountability. Table 4. Population by Race Caucasian Black Asian Hispanic Native American Percent eligible for free/reduced lunch TPS 36% 35% 2% 17% 10% 79.6% Oklahoma 60% 11% 2% 9% 19% 55.5% 12 Suspension cases in TPS are not equally distributed among these race categories. Table 5 shows suspension data for all schools in the study (all sites excluding alternative and charter schools). Population percentage differs slightly from information reported by the Office of Accountability. These slight changes may be attributed to the removal of alternative and charter schools, or due to the time period examined. (The Office of Accountability figures represent 2006; TPS data is for the academic year 2006-2007.) Suspension rates for Caucasian students are disproportionately low. This group represents 34.99% of the population, but only 24.56% of cases of suspension. Figures are also disproportionately low for Asian and Hispanic students. Native American students are suspended slightly more than the average, and Black students are suspended far more frequently than the average. These proportions are fairly consistent for PBS and non-PBS sites. Table 6 compares the percent of population to the percent of suspension cases for Cohorts 1 and 2. PBS sites have a lower percentage of Caucasian and Asian students and a higher percentage of Black and Hispanic students than the district as a whole. The Native American population is comparable. (Note: the Office of Accountability records the categories “Caucasian” and “Native American,” while TPS records the categories “White” and “Indian.” The variation in labels most likely does not impact membership in categories for the district as a whole.) Table 5. Suspensions by Race for TPS Cases per Student Caucasian 0.17 Black 0.37 Asian 0.06 Hispanic 0.12 Native American 0.25 Average 0.24 Percent of Pop. 34.39% 34.99% 1.45% 22.75% 10.06% Table 6. Suspensions by Race for PBS sites Cohort 1 Cohort 1 Percent of Percent of Population Cases Caucasian 26.24% 19.83% Black 38.07% 59.49% Asian 0.54% 0.12% Hispanic 26.04% 13.10% Native American 9.11% 7.47% Cohort 2 Percent of Population 23.75% 36.60% 0.72% 22.75% 10.15% Percent of Cases 24.56% 55.04% 0.36% 18.35% 10.64% Cohort 2 Percent of Cases 20.61% 5635% 0.21% 10.57% 12.27% High and low-level suspensions. In addition to examining cases of suspension it is useful to consider the severity of behaviors for which students are being suspended. For Cohort 1 in 2004-2005 low-level (level 1&2) suspension represented 71.37% of all suspension cases, compared to only 57.68% of all cases in non-PBS schools. High-level offenses 13 (levels 6, 7 and 8) represented only 2.04% of all cases in Cohort 1, but 4.91% in non-PBS sites. PBS was implemented in the following school year, 2005-2006. Figure 4 shows the reduction in percentage of level 1&2 suspensions for non-PBS sites, Cohort 1 and Cohort 2. A chi-squared analysis demonstrated that changes in Cohort 1 are significant within the cohort as well as compared to non-PBS sites. Figure 4. Percentages of Low-Level Suspensions across Time 57.68 55.93 Non-PBS Sites* 53.8 71.37 61.83 Cohort 1* 34.39 50.34 2004-2005 2005-2006 2006-2007 50.04 Cohort 2** 48.8 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 Level 1&2 Percent of Total Cases * Cohort 1 reduction compared to non-PBS district sites: 2(2)=10.73; p < 0.01 ** Cohort 2 implemented PBS in 2006. The significant reduction in Cohort 1’s level 1&2 suspensions may be attributed to PBS goals of managing low-level offenses in the classroom. This reduction in proportion reflects a reduction in cases. Pre-implementation Cohort 1 recorded 1159 low-level cases. In 2006-2007 only 281 low-level cases were recorded (2 (2) =20.49; p < 0.01). Overall cases were reduced from 1624 to 817. This difference is accounted for in the reduction of low-level cases. Both Cohort 1 sites achieved “high implementation” status according to the 2007-2008 site evaluations. Cohort 2 achieved reductions that are not well reflected in figure 1. Total cases were reduced 22.74% from 2480 in the pre-implementation year to 1916 in the first year of implementation. Low-level cases were reduced 19.98% from 1241 to 933. The proportion of low-level to total, however, remained similar. This may be due to the fact that Cohort 2 sites were more similar to non-PBS sites in the pre-implementation year. Three Cohort 2 schools achieved “high implementation” status in their 2007-2008 evaluations. One other elementary site was within 2 percentage points of reaching high implementation. (It would be considered unusual for many schools to achieve high status in the first year after implementation.) 14 Cohort 1 high-level offenses (6, 7 or 8) increased from 34 recorded in 2004-2005 to 116 recorded in 2006-2007. PBS leadership attributes this increase partly to implementation backlash from students with severe behavior problems, and partly to better awareness and monitoring by staff. (By spending less time on low-level offenses, staff may be able to better address severe offenses.) Revisions in the code of conduct, or changes in administrators’ policies and tolerances may also influence this figure. Cohort 2 recorded a small reduction in high-level offenses (111 to 93) after implementation. This actually represents a slight increase in proportion of high-level offenses (4.48% up to 4.85%) to the whole. Days of Suspension Another important variable is the number of days lost to suspension. A school’s enrollment, absences and suspensions are calculated to produce the Average Daily Attendance (ADA) figure. Districts are awarded funding according to this figure; therefore the number of days lost to suspension reduces TPS funding. Naturally this impacts all students- not just students with undesirable behaviors. Suspension time also reduces students’ instructional time, which is of concern in schools with low standardized test performance. Days of suspension for all students. The decrease in cases for Cohort 2 also represents a decrease in days lost to suspension. Before implementation, Cohort 2 students were suspended for an estimated 20,859.5 days yielding an estimated loss of $304,131.51 (or $63.75 per student). In 2006-2007 that figure was reduced to 16,732.5 days for an estimated loss of $245,967.75, or about $52.60 per enrolled student. This 19.78% improvement is noteworthy compared to the non-PBS school improvement of only 9.32%.The estimated cost benefit of about $58,163.76 breaks down to about $12.44 saved for each enrolled student (including students who were not suspended in this school year). Before implementation Cohort 2 suspensions cases averaged 8.4 days in length. In the following year Cohort 2 suspension length averaged 8.4 days as well. As PBS implementation continues, and as more PBS sites reach high-implementation status it is expected that discipline and behavior will continue to improve, and the district will continue to enjoy improved ADA and resulting financial savings. While Cohort 1 reduced cases of suspension, overall days lost to suspension increased. This may be attributed to the significant increase in high-level offenses (which generally yield a longer suspension). In 2004-2005 Cohort 1 lost an estimated $161,134.40 to suspensions. Cohort 1 students were suspended for an estimated 14,693 days in 20062007, up 10.52% from 13,295 in the pre-implementation year 2004-2005. Cohort 1’s two schools lost an estimated $215,987.10 in suspension days for 2006-2007 (or $146.83 per student enrolled). If Cohort 1 had maintained the low-level suspension rates from 20042005, an estimated 878 additional cases of suspension would have further increased the amount of funding lost to suspension. 15 Days of suspension for students in special education. In spite of the above figures, Cohort 1 did make significant gains in days suspended for students in special education. Cohort 2 also decreased days of suspension for special education students. Both groups recorded a greater decrease in this figure than non-PBS sites (see table 6). However, as mentioned above, the special education population decreased slightly over the period studied. Table 6. Special Education Suspension Days Cohort 1 2004-2005 2005-2006 2006-2007 Change % improvement 5134 4708 2878 -2256 49.94% decrease Cohort 2 Non-PBS sites 6395 6694 3611 -2784 43.54% decrease 24546 25395 14853 -9692.5 39.49% decrease When days per student are examined, the gains made in Cohorts 1 & 2 both remain impressive. PBS sites represented 21.61% of the special education population, but accounts for 34.21% of the district’s improvement in suspension days for students in special education. In their respective pre-implementation years Cohorts 1 & 2 suspended special education students an average of 12.14 and 6.73 days respectively. This disparity reflects the trend that higher level, longer suspensions are less common in elementary schools. In 2006-2007 Cohort 1 suspended students in special education an average of 8.22 days each, for a gain of 3.92 instructional days each. Cohort 2 suspended these students an average of 3.87 days each, for an average gain of 2.86 instructional days each. In 20062007, non-PBS sites suspended special education students an average of 3.19 days per student. This difference is consistent with the trend that Cohort 1 and 2 schools began the PBS process with significantly higher suspension rates than non-PBS sites. Suspensions in High-Implementing and Low-Implementing Sites Contrasting PBS schools to non-PBS schools suggests that the PBS process is indeed impactful, but examining the success of implementation with the TPS-SET instrument offers one more variable with which to study the impact of PBS. Of the six middle schools involved in the PBS process at the time of study, two achieved high implementation status according to the TPS-SET evaluation. Table 7 shows suspension data for high and low-implementation PBS sites. Cases per student, instructional days lost per student, average days of suspension per case, and the average cost of each suspension are all lower for high-implementation middle schools. High-implementation middle schools saved about $26.45 per case of suspension. The proportions of low, mid, and high-level offenses to total cases were comparable between the groups. 16 Table 7. High and Low-Implementation Middle Schools High Implementers Cases per student Days per student Days per case Average cost per case 0.70 5.50 7.89 $115.99 Low Implementers 0.94 9.07 9.69 $142.44 Non-PBS middle school suspensions averaged 9.57 days in length. High-implementation PBS middle schools saved an average of 1.68 instructional days per suspension for about $24.70 per case savings. The lower rate of suspension cases and days per student furthers the financial benefit associated with a higher ADA at high-implementation middle schools. Among the elementary schools implementing PBS there were not significant differences between high and low implementing schools. (However reference to table 2 shows that three of the four low-implementing middle schools scored lower than the lowest elementary school. The range among middle schools is 55.06; the range among elementary schools is just 27.74.) Before implementation PBS elementary schools, all in Cohort 2, averaged 2.95 days per case (or about $45.89 per case). After just one year of implementation this was reduced to 2.02 days per case (or about $29.68 per case, for a savings of about $16.32 per case). In this year non-PBS elementary schools averaged 3.13 days per case (costing TPS about $46.05 per case of suspension). As stated above, this savings combined with the reduced number of suspensions (from 359 to 187) yielded a substantial savings of about $9,869.10 for the seven elementary schools in Cohort 2. Cohort 3 Many Cohort 3 schools were selected by district feeder patterns. While each Cohort 3 site entered PBS voluntarily, an emphasis was placed on the elementary schools that feed PBS middle schools. Every elementary school feeding Clinton and 57% of elementary schools feeding Cleveland and Hamilton are present in Cohorts 2 or 3. After Cohort 3 implementation Madison, Gilcrease and Nimitz will all be fed by at least two PBS elementary schools each. PBS leadership hypothesizes that as these middle schools are filled with students who have experienced more years of School-wide Positive Behavior Support, school climate and discipline will improve even more dramatically than in the first years of implementation. Eventually students from PBS Cohort 2 and 3 elementary schools will feed into Cohort 1’s Rogers High School and Cohort 3’s Central High School. (At the time of study, McLain, Webster, and Memorial High Schools are fed by PBS middle schools but are not participating in the PBS process.) 17 Cohort 3 had no implementation of PBS during the period studied. However it should be noted that in the pre-implementation year 2006-2007, Cohort 3 demonstrated suspension data that was generally lower than the district as a whole. This may be attributed to the high number of elementary schools in Cohort 3 (10 of 11 are elementary). TPS elementary schools generally have lower suspension rates than middle school and high school sites. However an independent samples T-test indicates that Cohort 3 elementary schools did not differ significantly from non-PBS elementary schools for cases per student (M=0.04; SD=0.04; t(49)=0.56; p>0.05). Days per case, or average length of each suspension case, did not differ significantly either (M=2.79; SD=1.05; t(45)=0.83; p>0.05). The remaining Cohort 3 school, Central High School, had comparable suspension data to non-PBS high schools. Therapeutic Services Part of the school-wide PBS implementation process in Tulsa Public Schools is the provision of therapeutic services to students with intensive needs. School-wide PBS implementation is designed to improve the entire school- students at all levels of behavior. However, early/primary implementation does not target students with intensive needs. These students are targeted with another program. Originally termed Positive Behavior Intervention Services (PBIS) by TPS, for the purposes of this report these services will be called “therapeutic services” or “mental health services” in order to avoid confusion with the national PBIS program. Students enrolled in mental health services are served on-site by one of four local agencies (These agencies are Family & Children’s Services, DaySpring Community Services of Oklahoma, Associated Centers for Therapy, and Youth Services of Tulsa.) Some mental health service programs are in place in nonPBS sites. The primary measure used to track these students is the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale. Overall, the three years of data suggests that students enrolled in mental health services perform better at PBS sites than non-PBS sites. GAF score improvement and days lost to suspension illustrate these differences. Among students completing services at PBS schools in 2006-2007, scores were an average of 3.41 points higher than scores of students at non-PBS sites (figure 5). Among all students (including students who had not completed services by the end of 2006-2007) improvement for PBS students was also greater by an average of 2.85 points. 18 Figure 5. Average Change in GAF Score Average Change in GAF Score Among Students Completing Mental Health Services since 2004 4.63 Students from PBS Schools 1.22 All other (non-PBS) students 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 This is consistent with the philosophy that a school-wide approach to positive behavior is impactful for students all levels of behavior. For students who were enrolled in mental health services on site since 2004 (whether or not they had completed services at the time of survey) enrollment in a PBS school in 2006-2007 improved average suspension days. Among these students who were suspended at least once in 2006-2007, students in PBS schools were suspended an average of 9.87 fewer days. Cohort 2, which includes elementary school students, had a slightly lower average than Cohort 1. The average difference of 9.87 days produces an estimated cost savings of about $145.09 for each PBS-site student represented below. Furthermore, PBS schools in 2006-2007 averaged about two weeks of additional instruction for students receiving therapeutic services. This is an important factor, considering the high four-year dropout rate in TPS. 19 Figure 6. Average Days Lost to Suspension Average Days Suspended in 06-07 Among Students Enrolled in Mental Health Services since 2004 22.26 PBS Cohort 1 20.67 PBS Cohort 2 30.87 Not in a PBS school 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 Discussion It appears that implementing school-wide Positive Behavior Supports can positively impact schools at all grade levels. Judged primarily by changes in suspension, PBS implementation has significantly improved Cohort 1 and 2 sites. Continued implementation may continue to improve discipline at these schools. Recommendations for Future Study The Office of Special Education and Student Services should continue to monitor the progress of PBS sites. Data-based decision making (a core of PBS implementation) should include suspension data and referral data. EducatorsHandbook.com, the referral tracking tool now used at PBS sites, may be used by PBS teams to develop more specific site-based plans. Over time if PBS implementation affects referrals as it has affected suspensions, PBS may reduce the amount of time teachers spend dealing with referrals. Time lost to referrals and suspensions for students and teachers may be estimated. As fewer students are suspended for lower level infractions, the increased time they spend in class may result in improved academic performance. TPS should continue to track the improvements at PBS sites, and the impact that PBS sites have on the district as a whole. 20 Limitations This study may be affected by several limitations. All analyses are based upon the accuracy of data provided by TPS. Dropouts and transfers to other schools and other districts may have an impact on demographic and suspension data. Alternative and charter schools in TPS were not considered in this study. PBS leadership believes that suspension data may be underreported at some district sites, which would result in deflated figures. The seven-level suspension matrix is revised periodically, which might generate changes in the apparent severity of suspensions. Administrative changes occurred at some PBS sites (and some non-PBS sites) which might impact the way those sites manage discipline. The TPS-SET, as discussed above, was modified somewhat from the original Sugai, Lewis-Palmer, Todd & Horner SET 2.0 instrument, although correlational analysis suggests that TPS adaptations are consistent with the original instrument. Furthermore, any SET analysis (modified or not) is inherently limited by the availability of students and staff for interview. Random sampling may be influenced if certain groups of staff or students are off-site or otherwise unavailable during unannounced SET evaluation visits. Inadequate response in the administrator and PBS team surveys also present a limitation. The SET was developed in middle and elementary schools- not high schools. Using the SET in high school settings presumes that the same implementation guidelines and standards apply at all levels. 21 References Eber, L., Sugai, G., Smith, C. R. & Scott, T. M. (2002). Wraparound and positive behavior interventions and support in schools. Journal of Emotional & Behavioral Disorders, 10(3), 171-181. Retrieved August 20, 2007 from EBSCO database. Freeman, R., Eber, L., Anderson, C., Irvin, L., Horner, R., Bounds, M., et al. (2006). Building inclusive school cultures using school-wide positive behavior support: Designing effective individual support systems for students with significant disabilities. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 31(1), 417. Retrieved March 31, 2008 from EBSCO database. Handler, M. W., Rey, J., Connell, J., Their, K., Feinberg, A., & Putnam, R. (2007). Practical considerations in creating school-wide positive behavior supports in public schools. Psychology in the Schools, 44(1), 29-39. Retrieved April 29, 2008 from Wiley InterScience. Horner, R.H., Todd, A. W., Lewis-Palmer, T., Irvin, L. K., Sugai, G. & Boland, J. B. (2004). The School-Wide Evaluation Tool (SET): A research instrument for assessing school-wide positive behavior support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 6(1), 3-12. Retrieved March 31, 2008 from EBSCO database. Moore, M., & Snow, D. (2007). [School survey and suspension data]. Unpublished raw data. Muscott, H.S., Mann, E., Benjain, T.B., Gately, S., Bell, K.E., & Muscott, A.J. (2004). Positive behavioral interventions and supports in New Hampshire: Preliminary results of a statewide system for implementing schoolwide discipline practices. Education and Treatment of Children, 27(4), 453-475. Retrieved August 27, 2007 from EBSCO database. Office of Accountability. (n.d.) Profiles 2006 District Report. District: Tulsa. Retrieved March 24, 2008, from http://www.schoolreportcard.org/2006/reports/drc /200672I001.pdf Sugai, G., Lewis-Palmer, T., Todd, A., & Horner, R.H. (2001). School-wide evaluation tool. Eugene: University of Oregon. Wilcox, B. L., Turnbull III, R. & Turnbull, A. P. (2000). Behavioral issues and IDEA: Positive behavioral interventions and supports and the functional behavioral assessment in the disciplinary context. Exceptionality, 8(3), 173-187. Retrieved March 30, 2008 from EBSCO database. 0 Appendix 1. TPS-SET Subscore Correlations Correlations A A- Expectations Defined Pearson Correlation N B- Behavioral Expectations Taught Pearson Correlation C- On-going System for Rewarding D- System for Responding to Behavioral Violations E- Monitoring and Decision Making F- Management Sig. (2-tailed) .207 .169 .258 .303 .056 D E F G .003 .619 .478 .563 .373 .293 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 .730(**) 1 .622(*) .567(*) .609(*) .706(**) .477 .842(**) .017 .034 .021 .005 .085 .000 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 Pearson Correlation .146 .622(*) 1 .782(**) .838(**) .729(**) .330 .770(**) Sig. (2-tailed) .619 .017 .001 .000 .003 .249 .001 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 Pearson Correlation .207 .567(*) .782(**) 1 .803(**) .772(**) .571(*) .838(**) Sig. (2-tailed) .478 .034 .001 .001 .001 .033 .000 N N .003 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 Pearson Correlation .169 .609(*) .838(**) .803(**) 1 .904(**) .514 .864(**) Sig. (2-tailed) .563 .021 .000 .001 .000 .060 .000 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 Pearson Correlation .258 .706(**) .729(**) .772(**) .904(**) 1 .662(**) .911(**) Sig. (2-tailed) .373 .005 .003 .001 .000 .010 .000 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 Pearson Correlation .303 .477 .330 .571(*) .514 .662(**) 1 .751(**) Sig. (2-tailed) .293 .085 .249 .033 .060 .010 N N Weighted score .146 Weighted score .521 C 14 N N G- District-Level Support 1 Sig. (2-tailed) B .730(**) .002 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 Pearson Correlation .521 .842(**) .770(**) .838(**) .864(**) .911(**) .751(**) 1 Sig. (2-tailed) .056 .000 .001 .000 .000 .000 .002 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 N ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed) 14 0