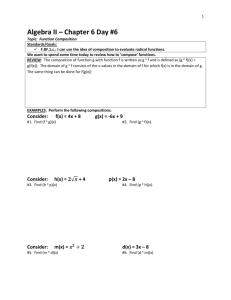

handout of class notes

advertisement

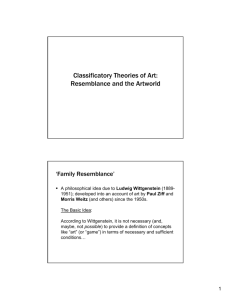

Chapter 5 Art, Definition and Identification I Against definition Neo-Wittgensteinianism: at as an open concept big claim on page 117 that teh Neo-Wittgensteinian philosophy of art has three parts 1- The open concept argument 1a- The positive side is the characterization of art as an open concept. 1b- The negative side is the rejection of the claim that art can be defined with necessary and sufficient conditions. [The argument for the negative side is given on page 212 and then later repeated on page 218. 1. Art can be expansive. 2. Therefore, art must be open to the permanent possibility of radical, change, expansion, and novelty. 3. If something is art, then it must be open to the permanent possibility of radical change, expansion and novelty. 4. If something is open to the permanent possibility of radical change, expansion and novelty, then it cannot be defined. 5. Suppose that art can be defined. 6. Therefore, art is not open to the permanent possibility of radical change, expansion and novelty. 7. Therefore, art is not art.] 2- The family resemblance method- the “reconstructive” part, because it reconstructs the way in which we identify and classify objects as art in terms of resemblances to paradigmatic artworks. [Family resemblance is discussed on pages 212-215. 214 has a nice example of how this can work in the second full paragraph; 215 has the key claim that not very many concepts can be defined in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions. Carroll doesn’t raise this point, but maybe the Wittgensteinian wants to say that the concept of art is even more open than concepts such as chair. We will discuss what being more or less open amounts to.] 3- The rehabilitative part- viewing existing theories of art not as theories of art but as contributions to art criticism [pages 216-217]. Objections to Neo-Wittgensteinianism The first objection is a criticism of the above argument as equivocating on the meaning of art [pages 218-221]. Carroll argues that premise 3 is plausible if you are talking about the practice of art, but not if you are talking about art itself (the actual, and possible, art works). Premise 5 on the other hand has to concern defining art itself. But 6 was supposed to follow from 5 because of 4, which followed from 3. But if 3 has a different meaning of the word “art” than 5 does, six does not follow. In this discussion he argues forcefully that one can think that premise 3 is true for the practice of art and still think that art can be defined. He asks us to consider the practice of doing science of which involves the kind of creativity adverted to in 3, so much so that there might be a sense in which 4 is true for the practice of doing science. But this doesn’t mean that science itself might not be defined. This is clearer if we distinguish between the context of discovering a scientific truth, which may involve radical creativity, and the context of justifying that truth (checking empirically to see if it is true) which may not. Maybe science itself is the set of truths that can be checked empirically. But then the process of doing science can be radically open, while science itself is still definable. The second objection is that the family resemblance method is too slack or too broad. It seems to entail that everything not only can be art (which fans of modern art might defend) but that everything is art. [pages 222-223] The third objection [pages 223-224] is that trying to fix the family resemblance from the previous objection is likely to render a definition that is sufficient for art, which contradicts the open question argument.