To Beam or not to Beam?

advertisement

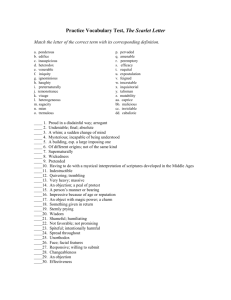

To Beam or not to Beam? A study in personal identity Beaming: Beaming: Beaming: Ways of Conceptualizing Beaming: Same Matter, “Matter Transport” “Recruited” Matter, “Information Transport” Question: • Which form(s) of transport is it rational to assume that you will survive? The Closest Continuer Schema • Proposed by Robert Nozick (1938-2002) • Identity is a relation that moves from one time-slice of an object to another time-slice of an object based on overall similarity. (easy) Closest Continuer Example: Closest to T1 Not Even Close T1 T2 Closest Continuer Rules: 1) Objects at T2 are compared only to other objects at T2 to determine which is the closest continuer to the object at T1 Closest Continuer Rules: 2) “Closest” must be clear. The Closest Continuer must be closer than any other claimant Closest: No CLOSEST Continuer T1 T2 Closest Continuer Rules 3) The Closest Continuer must be close enough (share enough qualitative similarity). Continuer: No Continuer T1 T2 Do you survive transport? What makes the person-slice at T2 the closest continuer of the person-slice at T1? T1 T2 Theories: 1. Matter Matters a) Body Matters (body includes brain) b) Brain Matters Theories: 1. Matter Matters a) Body Matters (body includes brain) b) Brain Matters - If this is your view of personal identity, which versions of transport would you survive? Kinds of Transport Matter Transport? Information Transport? Kinds of Transport Matter Transport? YES, Matter Transport preserves your original body (including brain) Information Transport? NO, Information transport uses different matter to assemble an exactly similar body (including brain) from recruited matter. Consequences of Matter Matters Views: • Body Matters: Consequences of Matter Matters Views: • Body Matters: – You don’t know who you are until you examine your body (thoroughly) Consequences of Matter Matters Views: • Body Matters: – You don’t know who you are until you examine your body (thoroughly) – You would not survive a brain transplant into another body (human or artificial) Consequences of Matter Matters Views: • Body Matters: – You don’t know who you are until you examine your body (thoroughly) – You would not survive a brain transplant into another body (human or artificial) – You would survive gradual prosthetic replacement of your body parts, but not a single wholesale replacement. Consequences of Matter Matters Views: • Brain Matters: Consequences of Matter Matters Views: • Brain Matters: – You don’t know who you are until you examine your brain (thoroughly) Consequences of Matter Matters Views: • Brain Matters: – You don’t know who you are until you examine your brain (thoroughly) – You would survive the placing of your brain in a blender, supposing that no parts were lost. Consequences of Matter Matters Views: • Brain Matters: – You don’t know who you are until you examine your brain (thoroughly) – You would survive the placing of your brain in a blender, supposing that no parts were lost. – There is something important about your brain aside from what it does. In order to endorse this view you must have an account of what this is, or else you don’t really have a Matter Matters view, but instead… Theories: 2. Mind Matters: • By ‘mind’ we mean psychology. A person’s psychology survives if their personality, memories, habits, beliefs, desires, etc. survive. - If this is your view of personal identity, which versions of transport would you survive? Kinds of Transport Matter Transport? Information Transport? Kinds of Transport Matter Transport? YES, Matter Transport preserves your original body (including brain), and so all the stuff your body and brain do (including sensing, remembering, desiring, etc.) is preserved Information Transport? YES, presumably it doesn’t matter which carbon atoms (e.g.) your body and brain have; they work the same way in any case. Consequences of Mind Matters View: • Matter Matters views are incorrect. Consequences of Mind Matters View: • Matter Matters views are incorrect. – You can survive prosthetic brain operations Consequences of Mind Matters View: • Matter Matters views are incorrect. – You can survive prosthetic brain operations – You can survive implantation into an android body, or into no body at all (e.g. a computer). Consequences of Mind Matters View: • Matter Matters views are incorrect. – You can survive prosthetic brain operations – You can survive implantation into an android body, or no body at all. – You can survive information transport. Psychological Continuers • When we apply the closest continuer schema to changes in a person over time, we seem to put more weight on psychological properties than physical properties. Psychological Continuers • When we apply the closest continuer schema to changes in a person over time, we seem to put more weight on psychological properties than physical properties. • If this view is correct, then we ought to have no objection to information transport. Objections to Information Transport • There are at least five major objections to the mind-over-matter closest continuer view: Objections to Information Transport There are at least five major objections to the mindover-matter closest continuer view. Three of them are addressed by Hanley: 1. The Argument from The Principle of Independence 2. The Argument from Phenomenology 3. The Argument from The Exclusion Principle Two of them are not (at lest not in this chapter): 4. The Duplication Argument 5. The Delay Argument Objection 1, The Argument from the Principle of Independence • The reasoning here is the same as in many other metaphysical disputes: – The Principle of Independence is obvious and clear – Some element of Hanley’s mind-over-matterclosest-continuer view is at odds with the Principle of Independence – Therefore, there is something wrong with Hanley’s view. Objection 1, The Argument from the Principle of Independence • To evaluate this reasoning, we will need to look at the Principle of Independence and see: – if it is as clear and obvious as the proponent of this objection says it is, and – if Hanley’s view is really at odds with it. The Principle of Independence • The Principle of Independence states that the question of whether identity has been preserved over time or through change should be independent of the presence or absence of some third entity. • For illustration, consider an example pulled from the TOS episode “What Are Little Girls Made Of?” The Principle of Independence On Hanley’s view, A is Kirk’s closest continuer because it combines Kirk’s psychological AND physical properties, but if A did not survive, then B would be the closest continuer. Kirk body Kirk mind T1 T2 Kirk body Android body Kirk mind Kirk mind A B The Principle of Independence In this case, A is Kirk’s closest continuer because it combines Kirk’s psychological AND physical properties, but if A did not survive, then B would be the closest continuer. Kirk body Kirk mind T1 T2 Kirk body Android body Kirk mind Kirk mind A B However, the principle of independence states that either A or B should either be Kirk or not be Kirk regardless of the existence of the other entity. The Principle of Independence The force of the objection is that B should either be or not be Kirk regardless of the existence or nonexistence of A, but that’s not how it comes out on Hanley’s view. Kirk body Kirk mind T1 T2 Kirk body Android body Kirk mind Kirk mind A B The Principle of Independence The force of the objection is that B should either be or not be Kirk regardless of the existence or nonexistence of A, but that’s not how it comes out on Hanley’s view. Kirk body Kirk mind T1 T2 Kirk body Android body Kirk mind Kirk mind A B IS KIRK The Principle of Independence The force of the objection is that B should either be or not be Kirk regardless of the existence or nonexistence of A, but that’s not how it comes out on Hanley’s view. Kirk body Kirk mind T1 T2 Kirk body Android body Kirk mind Kirk mind A B IS NOT KIRK The Principle of Independence • It is clear that this argument doesn’t have trouble with the mind-over-matter part of Hanley’s view, but rather with the closest continuer part of the view. The Principle of Independence • It is clear that this argument doesn’t have trouble with the mind-over-matter part of Hanley’s view, but rather with the closest continuer part of the view. • It is clear that this part of Hanley’s view is indeed at odds with the Principle of Independence. The Principle of Independence • It is clear that this argument doesn’t have trouble with the mind-over-matter part of Hanley’s view, but rather with the closest continuer part of the view. • It is clear that this part of Hanley’s view is indeed at odds with the Principle of Independence. • But is the PoI that clear and obvious? The Principle of Independence • Hanley’s replies to this point are honestly not very good. Briefly: 1. Hanley asserts that the PoI isn’t very plausible (without argument) 2. Hanley asserts that accepting the PoI means adopting a version of a matter-matters view (it doesn’t). 3. Hanley implies that giving up the closest continuer view means having to accept a soul view (also incorrect). The Principle of Independence A better response would be to point out that sometimes we must look around at other objects at some given T2 to fully make sense of continuation (or not) of identity, contrary to the PoI. The Principle of Independence Consider a case of cell division. If we only look at one cell at a time, we might say that each daughter cell preserves the identity of its parent cell. Instead, we see that there are two of them at T2, and conclude that identity has not been preserved at all and that there are two new cells. Objection 2, The Argument from Phenomenology • Recall that one consequence of the mindmatters view is that there is no difference between information transport and androidization or computerization (at least as far as personal identity is concerned). Objection 2, The Argument from Phenomenology • The argument from phenomenology proceeds as follows: – It is clear and obvious that androidization and computerization could not preserve phenomenology. – Phenomenology is essential to identity. – Therefore, Hanley’s view (or any other that allows identity to be preserved by androidization or computerization) is not a correct view of identity. Objection 2, The Argument from Phenomenology • Phenomenology refers to what it is like to have your mental states. Objection 2, The Argument from Phenomenology • Phenomenology refers to what it is like to have your mental states. • People commonly think that if they were turned into a functionally identical android, their mental states would feel different to them. (This is what motivates the first premise of this argument Objection 2, The Argument from Phenomenology • This objection sounds plausible to many, but it never actually gets off the ground (it is internally inconsistent). Objection 2, The Argument from Phenomenology • This objection sounds plausible to many, but it never actually gets off the ground (it is internally inconsistent). • Consider describing what it would be like to have your mental states, but have them feel different than your mental states. Objection 2, The Argument from Phenomenology • This objection sounds plausible to many, but it never actually gets off the ground (it is internally inconsistent). • The problem is that if all of your mental states felt different, they wouldn’t BE your old mental states. Objection 2, The Argument from Phenomenology • Further, this argument must outright deny functionalism and explain how the brain creates mental states that feel a certain way and cannot be replicated. • It must do this without appealing to any “special physics” (i.e. magic) that happens in brains. Objection 3, The Argument from the Exclusion Principle • Hanley includes this objection, not because it is very good, but because he runs into it often. Objection 3, The Argument from the Exclusion Principle • Here’s how it goes: – It just seems obvious that androidization and beaming are different processes – Hanley’s view treats them as the same – Therefore, Hanley’s view is mistaken Objection 3, The Argument from the Exclusion Principle • To respond to this position, Hanley needs to explore the first premise to figure out what it is that makes people thing that it is so clear that androidization and information transport are different. Objection 3, The Argument from the Exclusion Principle • Hanley thinks this premise is motivated by the Exclusion Principle Objection 3, The Argument from the Exclusion Principle • Hanley thinks this premise is motivated by the Exclusion Principle • The Exclusion Principle is a psychological tendency that people have to be fooled by the way that processes are described. Objection 3, The Argument from the Exclusion Principle • Hanley thinks this premise is motivated by the Exclusion Principle • The Exclusion Principle is a psychological tendency that people have to be fooled by the way that processes are described. • Specifically, processes that are described as detailed and scientific are less intuitive than processes that are undescribed, or described as magic. Objection 3, The Argument from the Exclusion Principle • Since beaming looks like magic, we can accept that the same person that disappears, reappears. • Since androidization looks like science, we cannot accept that the same person that has their parts replaced, persists. Objection 3, The Argument from the Exclusion Principle • Since beaming looks like magic, we can accept that the same person that disappears, reappears. • Since androidization looks like science, we cannot accept that the same person that has their parts replaced, persists. • The Exclusion Principle states that we can believe in the results of magical, but not of man-made processes. Objection 3, The Argument from the Exclusion Principle • Obviously, Hanley doesn’t think much of the Exclusion Principle. • There seems to be no rational basis for accepting the Exclusion Principle. Hanley’s conclusion • Since psychological properties are evidently preserved in matter transport, information transport, and androidization, it is rational to accept each procedure, and superstitious to refuse. Objection 4: The Duplication Argument • Recall that no two objects can share an identity on pain of contradiction. If there are two people, they have different identities, and if they share an identity, there can be only one of them. Objection 4: The Duplication Argument • Recall the standard description of the information transporter: – Your “pattern” is digitized, and then you are assembled at a new location, with the same physical pattern (and so the same psychological pattern) from matter that was already at the new location. Objection 4: The Duplication Argument • The process has one person disappearing in one place while one person appears in another place. Objection 4: The Duplication Argument • The process has one person disappearing in one place while one person appears in another place. • The argument from duplication starts by pointing out that these parts of the technology are incidental to how it operates, not essential to how it operates. Objection 4: The Duplication Argument • Specifically: – The original NEED NOT DISAPPEAR for the process to work. Objection 4: The Duplication Argument • Specifically: – The original NEED NOT DISAPPEAR for the process to work. – The number of appearing at the new location NEED NOT BE RESTRICTED TO ONE Objection 4: The Duplication Argument • Wait a moment, this talk of ‘disappearing’ sounds an awful lot like magic… Objection 4: The Duplication Argument • Wait a moment, this talk of ‘disappearing’ sounds an awful lot like magic…lets use the term ‘disintegrating’ instead and see if our willingness to go through the process changes. Info Transport + Phaser Case: • Step One: Scan the pattern at location 1 • Step Two: Integrate from recruited matter at location 2 • Step Three: Shoot the person at location 1 with phaser, to disintegrate them Info Transport + Phaser Case: • Any Takers? Info Transport + Phaser Case: • Any Takers? No? • If you’re not convinced that you would survive this process, then you should not be convinced that the person emerging at the end of more conventionally described info transport IS YOU. Objection 4: The Duplication Argument • Hanley could simply bite the bullet at this point and maintain that in spite of how we feel about the info transporter plus phaser case, we are just being superstitious. • Since our psychological properties really do survive this process, and since our identity really is identity of psychological properties, we really survive, so opposition is misguided. Objection 4: The Duplication Argument • If we follow Hanley, and allow that you really survive info transport + phaser, then the mind matters view has more serious trouble: Objection 4: The Duplication Argument • Consider what happens when the info transporter makes more than one person on the same pattern, both with recruited matter, then (as before) the original is phasered. Objection 4: The Duplication Argument • Consider what happens when the info transporter makes more than one person on the same pattern, both with recruited matter, then (as before) the original is phasered. • It is logically impossible for both to have the identity of the original, and the closest continuer schema is unable to tell the difference. Objection 4: The Duplication Argument • Consider what happens when the info transporter makes more than one person on the same pattern, both with recruited matter, then (as before) the original is phasered. • If identity is carried by psychological properties, then identity could be duplicated (because psychological states can be duplicated). Since identity cannot be duplicated, identity cannot be carried by psychological properties. Objection 5, The Delay Argument • The Duplication argument is an argument against surviving information transport. The Delay argument argues against the closest continuer view as it applies to either matter or information transport. • The Delay argument introduces a new aspect of transport to think about: More Ways of Conceptualizing Beaming: Delay Instantaneous Objection 5, The Delay Argument • While these cases may both seem reasonable, there is a limit to how instantaneous the instantaneous version can be. There must be either: – Some time between T1 when you are in one place and T2 when you are in another place (even if that time is very small). – Some time during which you are neither completely in one place nor completely in another. Objection 5, The Delay Argument • Recall that the closest continuer schema requires a continuer. • Since any concept of transport contains a period of discontinuity, even the closest continuer schema indicates that you would not survive transport (of any kind). • Consider the following example Objection 5, The Delay Argument Objection 5, The Delay Argument • Any takers? Objection 5, The Delay Argument • Any takers? • No? Why not? Objection 5, The Delay Argument • So if a break in continuity means a loss of identity (otherwise known as dying), then any form of transport kills you (at least according to the closest continuer schema) and at best creates a copy that thinks it’s the original. Life after Beaming • So if we do indeed survive matter or information transport, delayed or instantaneous, then it is for reasons other than psychological closest-continuation. Life after Beaming • So if we do indeed survive matter or information transport, delayed or instantaneous, then it is for reasons other than psychological closest-continuation. • What could those reasons be? Wrap-up on metaphysics • Not all metaphysical assumptions are equally good. Wrap-up on metaphysics • Not all metaphysical assumptions are equally good. • There are many things we can’t be sure of, so we must do the best we can to be creative and critical so as to at least do the best we can. Wrap-up on metaphysics • The things we say, think, and base decisions on in everyday life require metaphysical assumptions. Wrap-up on metaphysics • The things we say, think, and base decisions on in everyday life require metaphysical assumptions. • Metaphysical problems are not isolated to philosophy class.