A (Very) Short History of Volunteering

advertisement

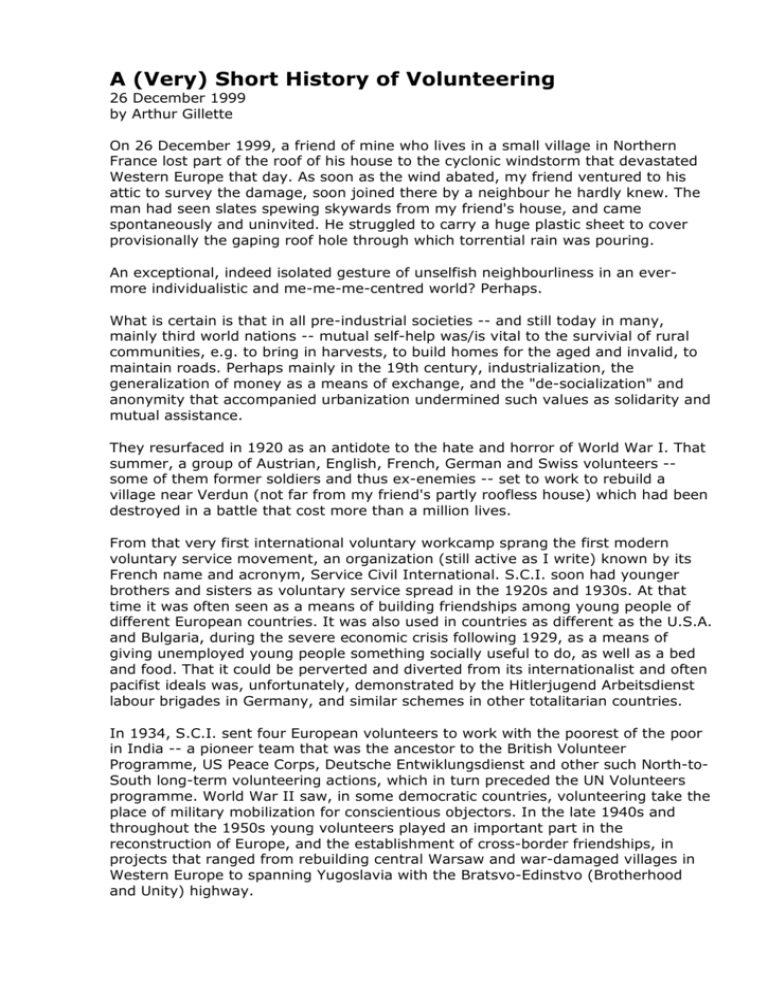

A (Very) Short History of Volunteering 26 December 1999 by Arthur Gillette On 26 December 1999, a friend of mine who lives in a small village in Northern France lost part of the roof of his house to the cyclonic windstorm that devastated Western Europe that day. As soon as the wind abated, my friend ventured to his attic to survey the damage, soon joined there by a neighbour he hardly knew. The man had seen slates spewing skywards from my friend's house, and came spontaneously and uninvited. He struggled to carry a huge plastic sheet to cover provisionally the gaping roof hole through which torrential rain was pouring. An exceptional, indeed isolated gesture of unselfish neighbourliness in an evermore individualistic and me-me-me-centred world? Perhaps. What is certain is that in all pre-industrial societies -- and still today in many, mainly third world nations -- mutual self-help was/is vital to the survivial of rural communities, e.g. to bring in harvests, to build homes for the aged and invalid, to maintain roads. Perhaps mainly in the 19th century, industrialization, the generalization of money as a means of exchange, and the "de-socialization" and anonymity that accompanied urbanization undermined such values as solidarity and mutual assistance. They resurfaced in 1920 as an antidote to the hate and horror of World War I. That summer, a group of Austrian, English, French, German and Swiss volunteers -some of them former soldiers and thus ex-enemies -- set to work to rebuild a village near Verdun (not far from my friend's partly roofless house) which had been destroyed in a battle that cost more than a million lives. From that very first international voluntary workcamp sprang the first modern voluntary service movement, an organization (still active as I write) known by its French name and acronym, Service Civil International. S.C.I. soon had younger brothers and sisters as voluntary service spread in the 1920s and 1930s. At that time it was often seen as a means of building friendships among young people of different European countries. It was also used in countries as different as the U.S.A. and Bulgaria, during the severe economic crisis following 1929, as a means of giving unemployed young people something socially useful to do, as well as a bed and food. That it could be perverted and diverted from its internationalist and often pacifist ideals was, unfortunately, demonstrated by the Hitlerjugend Arbeitsdienst labour brigades in Germany, and similar schemes in other totalitarian countries. In 1934, S.C.I. sent four European volunteers to work with the poorest of the poor in India -- a pioneer team that was the ancestor to the British Volunteer Programme, US Peace Corps, Deutsche Entwiklungsdienst and other such North-toSouth long-term volunteering actions, which in turn preceded the UN Volunteers programme. World War II saw, in some democratic countries, volunteering take the place of military mobilization for conscientious objectors. In the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s young volunteers played an important part in the reconstruction of Europe, and the establishment of cross-border friendships, in projects that ranged from rebuilding central Warsaw and war-damaged villages in Western Europe to spanning Yugoslavia with the Bratsvo-Edinstvo (Brotherhood and Unity) highway. But the Cold War threatened to freeze the heart and mind out of volunteering, and use it as a tool in superpower competition. Thanks in good part to UNESCO and its Coordinating Committee for International Voluntary Service (created in 1948) volunteers from East and West were soon, albeit symbolically, jointly "rusting" the "Iron Curtain". In the early 1960s, I myself, an American, took part in international voluntary workcamps in the U.S.S.R., G.D.R and Hungary -- and I can testify that they were not sleazy propaganda exercises, and the genuine exchanges sometimes arguments -- took place, while real friendships were formed. And, yes, voluteers from the East also travelled West. Emancipation from colonial rule gave birth to national volunteer movements throughout Asia, Africa and Latin America. Some were tiny and fragile: in Nigeria, the Lagos Voluntary Workcamps Organization was so poor it couldn't afford postage stamps and its members delivered invitations to potential student volunteers on foot. Other operations were huge : in 1960, 15- to 18-year-old secondary school students formed the backbone of the volunteer force that virtually eliminated illiteracy in Cuba. Long-term volunteering to assist developing countries took off in the 1960s and with it soon came calls to depoliticize it. To ensure that volunteers not be used as « soldiers » in the Cold War, the creation of a U.N. corps of volunteers was advocated. Already in the 1950s, UNESCO had successfully used small teams of volunteers from the U.S.A. and Jordan at its regional adult education centres in the Arab States (Sirs el Layyan, Egypt) and Latin America (Patzcuaro, Mexico). The 1970s dawned with the creation of the UN Volunteers programme. The last chapter of this (very) short history of volunteering concerns two end-ofthe-century aspects. First is the resurgence of volunteering in the ex-Socialist countries. As mentioned above, there had been volunteering in the Soviet era, and it was not all obligatory and nasty: some people now middle-aged indeed recall their stints as young volunteers with fond nostalgia. But a new kind of volunteering has emerged from the ruins, and has taken root in several countries, particularly in North-Eastern Europe, where the UNESCO- and EU-supported EASTLINKS Network forms a common denominator. The UN Volunteers programme's Azerbaijan Project offers a hopeful avenue of innovation in the Caucasus. The second aspect concerns age: with extending healthy longevity in industrialized countries, increasing numbers of qualified retired professionals are now finding satisfaction and enrichment by offering their services, abroad as well as at home. I think I have never seen a happier group of senior citizens than the team of 15 retired American school teachers I met a few years ago who were upgrading the quality of English teaching at Beijing University. What do I think of volunteering? First of all, I'm convinced that not all volunteering is good. When, for example, the neo-liberal State withdraws from its duties to the most disadvantaged members of a society, then the volunteers meant to take up the slack can be a shabby alibi for deregulated governmental irresponsibility. On the other hand, volunteering has played a crucial and positive role in my own life. From the time I participated, aged 20, in my first voluntary workcamp in a Black ghetto near Boston to today when, at 62 and now retired, I undertake volunteer assignments for various NGOs, volunteering has been a constant source of satisfaction, learning, revelation and -often -- joy. There is a saying in English: "Get something for nothing", which generally implies "gaining selfish material advantage without any personal investment". Thanks to volunteering, I have often been able to "give something for nothing" i.e. to "invest personally for no material advantage". The benefits to me have been anything but $$$ ! Arthur Gillette is the former Director of UNESCO's Division of Youth and Sports Activities and the ex-Secretary General of the Coordinating Committee for International Voluntary Service. He is also the author of "One Million Volunteers -The Story of Youth Service" and "New Trends in Service by Youth".