THE TRIAL COURT`S [IMPLIED] FINDING THAT PENAL CODE

advertisement

![THE TRIAL COURT`S [IMPLIED] FINDING THAT PENAL CODE](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007718470_2-579e220018ed51dbd4d29d0fed2ee48f-768x994.png)

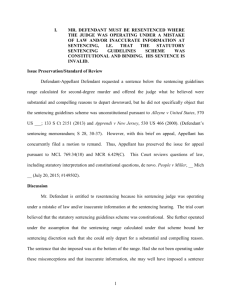

THE TRIAL COURT’S [IMPLIED] FINDING THAT PENAL CODE SECTION 654 DOES NOT PRECLUDE THE IMPOSITION OF A CONSECUTIVE SENTENCE ON COUNT [TWO] VIOLATED APPELLANT’S RIGHT, UNDER THE SIXTH AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS, TO A JURY TRIAL UNDER THE “REASONABLE DOUBT” STANDARD AS TO EVERY FACT LEGALLY ESSENTIAL TO PUNISHMENT A. Introduction. Under Penal Code section 654, a sentencing court has no authority to impose multiple punishment (i.e., consecutive sentences) for two or more offenses committed as part of the same course of criminal conduct, in the absence of substantial evidence and a court finding (explicit or implicit) that the defendant possessed a separate criminal objective for each offense of conviction. (See Neal v. California (1960) 55 Cal.2d 11, 19 [Penal Code section 654 precludes multiple punishment not just for multiple offenses committed as a result of a single act, but also for multiple offenses committed as a result of a single course of conduct with a single criminal objective]; People v. Hester (2000) 22 Cal.4th 290, 295 [“a court acts in excess of its jurisdiction and imposes an unauthorized sentence when it fails to stay execution of a sentence under section 654.”].) In light of this rule, and the United States Supreme Court’s opinions in Apprendi v. New Jersey (2000) 530 U.S. 466, 490, and Blakely v. Washington (2004) 542 U.S. 296, 303-304, 313, which hold that criminal defendants are entitled to a jury trial under the beyond-a-reasonable-doubt standard as to every fact “legally essential to punishment,” appellant submits in this argument that criminal defendants in California are entitled to a jury trial (under the Sixth Amendment) and to application of the beyond-a-reasonabledoubt standard (under the Fourteenth Amendment) as to determinations concerning the applicability of Penal Code section 654's multiple-punishment ban.1 1 A closely related issue is presently pending in the United States Supreme Court in Oregon v. Ice, 07-901, which was argued on October 15, 2008. In Ice, the High Court is considering whether the Apprendi/Blakely rule applies to the imposition of consecutive sentences under Oregon Revised Statutes 137.123, which provides: (1) A sentence imposed by the court may be made concurrent or consecutive to any other sentence which has been previously imposed or is simultaneously imposed upon the same defendant. The court may provide for consecutive sentences only in accordance with the provisions of this section. A sentence shall be deemed to be a concurrent term unless the judgment expressly provides for consecutive sentences. (2) If a defendant is simultaneously sentenced for criminal offenses that do not arise from the same continuous and uninterrupted course of conduct, or if the defendant previously was sentenced by any other court within the United States to a sentence which the defendant has not yet completed, the court may impose a sentence concurrent with or consecutive to the other sentence or sentences. (3) When a defendant is sentenced for a crime committed while the defendant was incarcerated after sentencing for the commission of a previous crime, the court shall provide that the sentence for the new crime be consecutive to the sentence for the previous crime. (4) When a defendant has been found guilty of more than one criminal offense arising out of a continuous and uninterrupted course of conduct, the sentences imposed for each resulting conviction shall be concurrent unless the court complies with the procedures set forth in subsection (5) of this section. B. Under the United States Supreme Court’s Opinions in Apprendi and Blakely, All Facts (Other Than Prior Convictions) That Are Legally Essential to a Defendant’s Sentence Must Be Submitted to a Jury and Found True Beyond a Reasonable Doubt. In Apprendi v. New Jersey, supra, the United States Supreme Court held that, “[o]ther than the fact of a prior conviction, any fact that increases the penalty for a crime beyond the prescribed statutory maximum must be submitted to a jury, and proved beyond a reasonable doubt.” (Id., 530 U.S. at p. 490.) In Blakely v. Washington, supra, the Court held that “the relevant ‘statutory maximum’ [referred to in Apprendi] is not the maximum sentence a judge may impose after finding additional facts, but the maximum (5) The court has discretion to impose consecutive terms of imprisonment for separate convictions arising out of a continuous and uninterrupted course of conduct only if the court finds: (a) That the criminal offense for which a consecutive sentence is contemplated was not merely an incidental violation of a separate statutory provision in the course of the commission of a more serious crime but rather was an indication of defendant’s willingness to commit more than one criminal offense; or (b) The criminal offense for which a consecutive sentence is contemplated caused or created a risk of causing greater or qualitatively different loss, injury or harm to the victim or caused or created a risk of causing loss, injury or harm to a different victim than was caused or threatened by the other offense or offenses committed during a continuous and uninterrupted course of conduct. (ORS 137.123, 1987 c.2 §12; 1991 c.67 §29; 1991 c.111 §14; 1995 c.657 §2; 2003 c.14 §58.) he may impose without any additional findings.” (Blakely, supra, 542 U.S. at pp. 303304, emphasis in original.) “[T]he ‘statutory maximum’ for Apprendi purposes is the maximum sentence a judge may impose solely on the basis of the facts reflected in the jury verdict or admitted by the defendant.” (Blakely, supra, 542 U.S. at p. 303, emphasis in original; and see id. at p. 313 [“As Apprendi held, every defendant has the right to insist that the prosecutor prove to a jury all facts legally essential to the punishment.”] Emphasis in original.) The High Court recently reiterated this “bright line rule” in Cunningham v. California (2007) 549 U.S. 270 [127 S.Ct. 856, 873, 166 L.Ed.2d 856]. C. Since a Finding That the Defendant Harbored Discrete Criminal Objectives in Committing Two Contemporaneous Offenses Is, Under Section 654, Legally Essential to the Imposition of Consecutive Sentences for the Offenses, the Defendant’s Sixth Amendment Right to Trial by Jury and Fourteenth Amendment Right to Due Process Attach to Such Findings. 1. State rules applicable to section 654 determinations. Penal Code section 654, subdivision (a), precludes multiple punishment for a criminal act that violates more than one penal statute. (Id.) Under Neal v. California, supra, 55 Cal.2d 11, 19, the multiple-punishment bar of section 654 applies not only to a single act or omission, but to multiple acts and omissions that are part of one indivisible course of conduct. The “Neal test” for the indivisibility of a course of conduct focuses on the criminal objective(s) of the defendant: “Whether a course of criminal conduct is divisible and therefore gives rise to more than one act within the meaning of section 654 depends on the intent and objective of the actor. If all of the offenses were incident to one objective, the defendant may be punished for any one of such offenses but not for more than one.” (Ibid.) A judge has no more discretion in determining the applicability of section 654's multiple-punishment bar than a jury has in resolving a defendant’s guilt: they are both reviewed under the substantial-evidence test. (See People v. Osband (1996) 13 Cal.4th 622, 730; People v. Saffle (1992) 4 Cal.App.4th 434, 438.) And a judge’s error in failing to apply the multiple-punishment bar of section 654 is not simply an abuse of sentencing discretion, but an unauthorized sentence. (People v. Hester, supra, 22 Cal.4th 290, 295; People v. Scott (1994) 9 Cal.4th 331, 354, fn. 17; People v. Perez (1979) 23 Cal.3d 545, 549-550, fn. 3 [“Errors in the applicability of section 654 are corrected on appeal regardless of whether the point was raised by objection in the trial court or assigned as error on appeal.”]; and see People v. Shelton (2007) 37 Cal.4th 759, 766-770 [recognizing significant distinction between a trial court’s exercise of sentencing discretion and its statutorily circumscribed authority to impose multiple punishment under section 654].) 2. The Apprendi-Blakely rule applies to section 654 determinations. In light of the above-listed rules regarding section 654 determinations, and the impact that such determinations have on a defendant’s sentence, it is clear that, under Apprendi, supra, and Blakely, supra, a defendant’s rights to trial by jury and to acquittal in the absence of a jury’s finding of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt attach to section 654 determinations. The cases that have addressed this contention have rejected it. (See People v. Cleveland (2001) 87 Cal.App.4th 263; People v. Solis (2001) 90 Cal.App.4th 1002, 1021-122; People v. Retanan (2007) 154 Cal.App.4th 1219, 1228; People v. Steele (2008) 164 Cal.App.4th 1195, 1211 [holding that the question of whether the Apprendi/Blakely rule applies to Penal Code section 654 determinations is controlled by the California Supreme Court’s opinion in People v. Black (2005) 35 Cal.4th 1238, 12631264].) However, the analysis used in these cases is constitutionally flawed. The lead case is People v. Cleveland, supra, a post-Apprendi, pre-Blakely case. In Cleveland, the defendant argued that the issue of whether he had more than one criminal objective for multiple offenses committed during a single course of criminal conduct was a factual question that Apprendi required the jury to decide, using the beyond-areasonable-doubt standard. In a 2-1 decision, the appellate court disagreed, holding that section 654's application in that case did not violate Apprendi because the question of whether section 654 operates so as to preclude consecutive sentences does not involve the determination of any fact that could increase the penalty for a crime beyond the statutory maximum. (Cleveland, supra, 87 Cal.App.4th at p. 270.) The court reasoned that there is no federal right to a jury trial on section 654 determinations, because section 654 is a “sentencing ‘reduction’ statute” – not a sentencing “enhancement.” (Ibid.) Justice Johnson dissented, opining that “the United States Supreme Court opinion in Apprendi v. New Jersey—and the rationale it embodies—requires the jury rather than the trial judge to determine whether a defendant committed these offenses with multiple objectives and thus was susceptible to consecutive sentences rather than concurrent sentences for this course of criminal conduct.” (Cleveland, supra, 87 Cal.App.4th at pp. 272-273, Johnson, J., dissenting.) Justice Johnson disagreed with the majority’s characterization of a section-654 determination as one effecting a sentence “reduction” rather than a sentence “enhancement.” (Id. at pp. 280-281, Johnson, J., dissenting.) Appellant submits that Justice Johnson’s opinion is the better reasoned one. “[T]he relevant inquiry is not one of form, but of effect – does the required finding expose the defendant to a greater punishment than is authorized by the jury's guilty verdict?” (Apprendi, supra, 530 U.S. at p. 494.) Thus, the Cleveland majority’s reliance on labels (viz., “sentencing reduction statute” and “sentencing enhancement”) is misplaced. And, as Justice Johnson noted in his dissent, the majority’s characterization of section 654 as a “sentencing reduction statute” rather than a “sentencing enhancement” is also inaccurate. (Cleveland, supra, 87 Cal.App.4th at p. 280, Johnson, J., dissenting.) Section 654 is not a statute, like Penal Code section 1385, that gives a judge discretion to reduce a defendant’s sentence by striking a sentence-enhancing fact found true by a jury beyond a reasonable doubt. To the contrary, section 654 precludes additional punishment for additional crimes committed by a defendant that are part of the same “act” (viz., done with the same criminal intent and during the same course of conduct) as the principle offense. (§ 654, subd. (a) [“An act or omission that is punishable in different ways by different provisions of law shall be punished under the provision that provides for the longest potential term of imprisonment, but in no case shall the act or omission be punished under more than one provision.” Emphasis added]; and see Neal, supra, at p. 19.) So, “sentencing reduction statute,” if anything, is a misnomer for section 654. And, again, the label is irrelevant. A proper application of the Apprendi/Blakely rule requires that the question of whether or not a defendant had only one criminal objective should go to the jury, because only its adverse resolution allows the judge to exceed the punishment that otherwise would have been authorized by section 654 had the issue been resolved the other way. (See Blakely, supra, 542 U.S. at pp. 303-304 [“When a judge inflicts punishment that the jury's verdict alone does not allow, the jury has not found all the facts ‘which the law makes essential to the punishment,’ and the judge exceeds his proper authority.”] Citations omitted; emphasis added.) Blakely makes this quite clear. “Whether the judge’s authority to impose an enhanced sentence depends on finding a specified fact (as in Apprendi), one of several specified facts (as in Ring [v. Arizona (2002) 536 U.S. 584]), or any aggravating fact (as here), it remains the case that the jury’s verdict alone does not authorize the sentence. The judge acquires that authority only upon finding some additional fact.” (Blakely, 542 U.S. at p. 305, emphasis added; see also id. at p. 306 [“Apprendi ... ensur[es] that the judge’s authority to sentence derives wholly from the jury’s verdict.”].) Cleveland illustrates the problem with attempting to place labels (i.e., “sentencingreducing” vs. “sentence-enhancing”) on certain facts to determine whether they can be taken away from the jury. Some facts must be litigated and found true (or untrue), before they can be so labeled. It is the factfinder’s resolution of the “Neal” test that determines how section 654 affects the defendant’s sentence. Under Neal, the question of whether or not a defendant harbored a single criminal objective during his course of criminal conduct is one whose resolution, favorably or unfavorably to the defendant, will determine its legal effect on the defendant’s punishment. Thus, it is illogical to try to brand this unresolved factual question with a sentencing label that prejudges its resolution. And doing so in order to remove the factual question from the Constitution’s reach violates “Apprendi’s bright line rule.” 3. This issue should no longer be viewed as being controlled by the California Supreme Court’s opinion in Black I. In People v. Black (2005) 35 Cal.4th 1238 (“Black I”), the California Supreme Court held that the Apprendi-Blakely rule does not apply to a trial court’s decision to impose consecutive rather than concurrent sentences under Penal Code section 669. (Id. at pp. 1261-1262.) In dicta, the court expressed the view that the right to a jury trial also does not attach to sentencing determinations required by Penal Code section 654, because such determination are “analogous to the decision whether to sentence concurrently.” (Black I, supra, at p. 1264.) However, in its recent, post-Cunningham opinion in People v. Black (2007) 41 Cal.4th 799 (“Black II”), the California Supreme Court, while reiterating its holding of Black I that Apprendi does not apply to a trial court’s decision to impose consecutive rather than concurrent sentences under Penal Code section 669, did not reiterate its dicta from Black I that the same conclusion applies to sentencing determinations required by section 654. (See Black II, supra, 41 Cal.4th at pp. 820-823.) In any event, the California Supreme Court’s suggestion in Black I that sentencing determinations under Penal Code section 654 are analogous to those under Penal Code opinion 669 for purposes of Apprendi is incorrect and inconsistent with that court’s own jurisprudence highlighting the important distinction between discretionary sentencing determinations under section 669 and those as to which the trial court’s authority to impose consecutive sentences is circumscribed by section 654. (See People v. Shelton, supra, 37 Cal.4th 759, 766-770 [post-Black I opinion holding that a challenge of a sentencing court’s imposition of consecutive sentences on Penal Code section 654 grounds constitutes a challenge, not of the trial court’s exercise of sentencing discretion, but of its legal authority to impose consecutive sentences]; People v. Hester, supra, 22 Cal.4th 290, 295; People v. Scott, supra, 9 Cal.4th 331, 354, fn. 17.) Because Penal Code section 654 prohibits consecutive sentences based on a single course of conduct, a consecutive term imposed on a transactionally related count is not authorized in the absence of a finding (express or implied) that the offense was committed for a different criminal objective than the count(s) to whose sentence it is being imposed consecutively. (Neal, supra; Shelton, supra; People v. Latimer (1993) 5 Cal.4th 1203, 1216; and see People v. Hester, supra; People v. Scott, supra.) Thus, whether or not the same is true as to a factual determination underpinning a discretionary sentencing decision under Penal Code section 669, a determination required by Penal Code section 654 is “legally essential” to the imposition of a consecutive sentence within the meaning of Apprendi and Blakely. (See Blakely, supra, 542 U.S. at p. 313 [“As Apprendi held, every defendant has the right to insist that the prosecutor prove to a jury all facts legally essential to the punishment.”] Emphasis in original.) D. Apprendi/Blakely Error Occurred as to the Trial Court’s Section 654 Determination in this Case, Requiring Reversal of that Determination. [Discuss facts of current case and interrelationship of consecutively-punished offenses for purposes of Penal Code section 654. Incorporate by reference argument contained in separate, state-law claim that the imposition of consecutive terms violates Penal Code section 654. Explain how the evidence in the case presented a triable question as to whether appellant harbored only a single criminal objective for purposes of section 654 and thus renders the trial court’s denial of a jury trial on that question reversible under Chapman v. California (1967) 386 U.S. 18, 24 (reversal is required unless it appears “beyond a reasonable doubt that the error complained of did not contribute to the verdict obtained”) and Washington v. Recuenco (2006) 548 U.S. 212. E. The Issue Is Cognizable in this Appeal Despite Defense Counsel’s Failure to Raise it Below. Any claim by respondent that appellant has waived or forfeited this issue by failing to raise it below would be unavailing. As acknowledged above, every California court yet to consider the question has held that the Apprendi/Blakely rule does not apply to Penal Code section 654 determinations. (See discussion at pp. __, ante.) And, at the time of appellant’s sentencing, the United States Supreme Court had not (and, as of the date of this brief’s filing, still has not) recognized that the Apprendi/Blakely rule applies to the imposition of consecutive sentences.2 Thus, any objection in the trial court to the imposition of consecutive sentences on the ground that the Apprendi/Blakely rule applies to Penal Code section 654 determinations would have been futile. Therefore, as the California Supreme Court recognized in Black II, supra, and People v. Sandoval (2007) 41 Cal.4th 825, appellant was not required to raise an Apprendi/Blakely objection to the imposition of consecutive terms in order to preserve that objection for appeal. (See Sandoval, supra, at p. 837, fn. 4; Black II, supra, 41 Cal.4th at pp. 810-812.) 2 However, as previously noted (see footnote 1, ante), the issue is presently pending in the United States Supreme Court in Oregon v. Ice, 07-901.

![[implied] finding that penal - Central California Appellate Program](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008358364_1-576f4816c89f8aa251f7a3b4d617423c-300x300.png)