Bóthar LCVP PowerPoint - Teachers` notes

advertisement

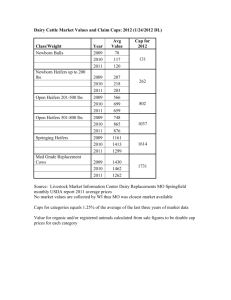

Bóthar na mBó PowerPoint Presentation LCVP Link Modules Slide Number and Notes: 1. Bóthar: meaning a road or path, but deriving from a more ancient term meaning a cow path. The word bó, of course, means a cow. In ancient Ireland a path or track was called a bóthar if one cow could stand across it and graze the margins while another passed behind at the same time. Cows are symbols of wealth in many societies. 2. Bóthar can be studied under the following parts of the LCVP Syllabus: Link Modules Unit 3: Local Voluntary Organisations/Community Enterprises or Unit 4: An Enterprise Activity 3. NGO. Non-Governmental Organisation. Bóthar is somewhat like other NGOs students will have heard of: Trócaire, Concern, Goal, Oxfam, etc. They all do important and specialised work in many areas, such as providing schools and teachers, hospitals and doctors, emergency food relief in places with famine, and so on. Bóthar leaves this specialised work to those who have the necessary expertise in it; instead, Bóthar concentrates on its own area of expertise: using farm animals in international development. Essentially, Bóthar supplies farm animals and training to poor people in many countries and through this they are assisted to lift themselves out of poverty. 4. Bóthar’s area of specialisation in development assistance. 5-10. Bóthar projects are located in Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America and the Middle East. The detailed maps and countries are in the following slides. This is not a complete list, but a representative sample. Countries may vary slightly over time as individual projects are completed and others begin. A quick comparison might be made to the size of Ireland compared to other parts of the world. For example, Tanzania, one of Bóthar’s main African project countries, has a land mass of over 886,000Km2, about 13 times the size of Ireland (68,890 Km2). Uganda: this is where Bóthar started, in 1991 and there are hundreds of Irish dairy cows in southern Uganda, as well as many pass-on offspring and others resulting from the AI and crossbreeding programme. Tanzania: this was the destination country of all Bóthar’s dairy goat airlifts up to 2005, when a programme was begun in Zambia. Malawi: this is another African country to which Bóthar heifers have been airlifted. With Eastern Europe, which looks very confusing, most students will be able to identify Italy on the map, so this will help to locate the region. 11. Dairy heifers and dairy goats. Bóthar airlifts heifers, not cows. Do the students know what a heifer is? (A young cow that has not had a calf. When she has her first calf she will begin giving milk to feed the calf; then she is a cow. Bóthar always sends in-calf heifers, so that shortly after they arrive they will have the calf and then the family will have not one animal but two.) 12. Why cows and goats? animals. The main reasons for working with these The following few slides tell something about animals that Bóthar works with which we do not usually find in Ireland, so they do not need to be airlifted. 13 Camels. (Kenya) A camel will give c. 5 litres of milk per day. Camels also pull the ploughs so the farmers can plant their seeds. The Bóthar camel programme among the East Pokot tribe is run by an Irish Holy Ghost Missionary. The East Pokot people are pastoralists who traditionally herded native zebu cattle. However, climate change meant the animals could no longer withstand the harsh conditions and these dairy camels provided a viable alternative. 14 Bees. Bóthar supports bee projects in five African countries: Ghana, Cameroon, Uganda, Tanzania and Zambia. This is Ghana. Families live in forest areas in central Ghana. Three hives are distributed per family. Each hive makes 15 litres of honey per annum. The honey is high quality and organic. There are c.40,000 bees per hive. The bees also cross-pollinate the fruit and nut trees in the forest, leading to up to 50% extra crop yield. Beekeeping may seem exotic and unusual but it is a valuable source of income here. Much training is involved. 15 Chicks. Sale of eggs enables the families to buy essentials such as food, clothing and medicine; also to pay for education and sometimes build improved housing. Fish. A river trout project in Moldova - fish farming in mountain streams. The young trout are called fingerlings. These projects are in state-run orphanages. Many young people end up in these institutions because their parents cannot afford to feed or educate their children, and feel they will have a better chance in these facilities. These young people are known as Economic Orphans. The fish farms are constructed in ponds fed by mountain streams and provide a source of nutrition and income. Pigs (Burkina Faso, Malawi, Uganda) Pigs have large litters (10-12+) twice yearly. They are used for meat. In Africa, European breed such as these must be kept in the shade as strong sunlight would cause diseases. They are far more productive than the native pigs which wander around the villages. Some 95% of water buffalo are to be found in parts of India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Thailand and Pakistan, and are the main bovine species in that region. The domesticated animals are multi purpose and can be used for dairy, meat or draught purposes. They can weigh anything from 400-900kg. In common with regular cattle their manure can be used as fertiliser or dried and made into fuel. Unlike cattle or oxen, which have to be driven from behind when carrying a load or ploughing, farmers can walk alongside or ahead of water buffalo, they instinctively follow. That is the end of the exotic or indigenous animals. The next few slides return to the heifers and goats for some details on Bóthar’s airlifts. 16. This is Shannon airport from where most of the airlifts depart 17. Irish Dairy goats, having arrived at Kilimanjaro International Airport, in N. Tanzania. 18. Stages in the journey. Bóthar uses a special, government-approved facility called a lairage centre to gather all the animals together prior to travelling. Vets examine the animals and certify them as fit to travel. They check their testing papers to see that they are in test for TB and brucellosis. The animals are inoculated against blackleg. They are fed and watered and have a rest. We are lucky that these valuable animals are all donated free of charge to Bóthar by generous farmers around the country, and great care is taken to ensure that they are safe, healthy and comfortable. Also, donor farmers go to the trouble of driving them to the lairage centre from all parts of the country on the day of the collection. From the lairage centre the heifers travel by road to Shannon airport. The Bóthar transport vehicles have to be very modern and well equipped, again for the safety and comfort of the animals. On this one, the floors are hydraulic and go up and down, so you can put two floors of heifers or three floors of goats aboard. Wherever the animal is standing she can have easy access to feed and water; also the entire truck is air conditioned so they will not be too warm. It is important to treat your animals well. Students might be made aware of the concept of the unwritten social contract that has existed between mankind and animals since they were first domesticated thousands of years ago. This is the idea that, as these animals are not wild and cannot survive by themselves as wild animals do, in return for the services they give to us – milk, meat, eggs, hide, etc. etc. - humans provide them with shelter, food and a good quality of life. Sadly, in recent times, and all too often, economic factors have led to animals being mistreated badly and used as a mere commodity. Bóthar’s animals are treated as one of the family in their new homes, and will routinely live longer there than they do here. The more benign climate and lack of stress from having to be housed indoors in the winter are factors in this. 19. Here we are inside a DC8 cargo jet. Bóthar always sends Holstein Friesian heifers, the familiar Irish black and white breed, because they adapt well and give lots of good-quality milk. 20. This is how the animals are put onto the plane. Having walked up the ramp, five or six of them go to the rear of the plane and then a special penning gate is put across. Then another five or six follow and another gate is put in place, and so on. This ensures and even distribution of weight along the plane’s length. In the case of dairy goats, each pen will comfortably accommodate about 30 animals. 21. Advantages of air transport. Bóthar animals travel by air as this is the quickest and least stressful method, even though it is very expensive. If the animals were transported by sea the journey would take many days and they would be exhausted after it – this would not be fair or proper treatment. 22. On departure from the airport in Africa, the animals are first put into another special facility called a quarantine. The animals will spend two weeks here. It is like a farm, but they are separated from all other animals. They have a rest and are checked again to see if they are all right after journey. Their health status must by law also be checked once again as receiving countries are naturally anxious to prevent disease from entering the country. At this stage the families can come in and get used to them without having to take them away. 23. Distribution. Photo from Tanzania – schoolboys on the way home from school. A dairy goat being taken in the truck to her new family. Vehicles must be strong and drivers must go slowly as there are very few proper roads and there are many rocks and potholes on the track roads. Often animals will be allocated by lottery among the group of recipients. This system is transparent and fair to all. 24-25. Yield comparisons of Irish pure-bred dairy cows and goats in comparison to local African animals. The indigenous animals are used for meat and, in the case of cattle, for draught power – pulling ploughs and so on. The hides are used for leather. They are not really dairy animals and a comparison with the milk yields of the Irish animals will show why the Irish cows and goats are so valuable and why the families will prize them highly and look after them so well. 26. Training of recipients. Training is a very important part of the Bóthar story. We never give an animal to a family unless they have been fully trained first. When somebody makes a donation to Bóthar, about half of that money goes to pay the cost of the airfare of the animal, in the case of heifers or goats, or of purchasing the animal if it is one of the exotic ones; the other half goes mostly towards the cost of training the farmer. 27. Passing on the Gift. This is another cornerstone of the Bóthar story. The students may already be familiar with it. Main points: the sponsored animals are given to the families not as a gift but as an in-kind loan – just like you or I would go to the Credit Union and get a loan to buy a new bicycle. The CU wants its money back and we must repay the loan before we own the bike. It is the same with the animals. How do the families repay the loan? Do they give us the animal back? Do they pay us in money? No. When the cow has a calf or the goat has a kid, if it is a female, they pass it on to another poor family. They also pass on the training. In this way they have given on the same things that they received themselves – an animal and training. Then, and only then, do they legally own the first animal, and they have papers to prove it. How will the second family repay their loan? They will pass on to a third family, and so on. So, you are not only helping one family but a whole line of them into the future. Why is it the females that are passed on? Because they give the milk and have the offspring. What happens if it is a male – do they kill it for meat? No, they can keep it if they want, but usually another farmer who has more money will give them a good price for it. He will use it to cross-breed with his own African animals and the calves or kids that are born will be better than he had before and give more milk, so the males are valuable too. Pass-on ceremonies. Often several families in a village will pass on at the same time. Everyone has a big celebration – singing and dancing etc. We can understand the families receiving the pass on animals being happy, but why would the families having to pass on a valuable animal to someone else also feel happy? Partly because they are helping their neighbours, but there is something else very important: they will gain dignity from giving this gift so that they no longer feel like dependants, but rather have the sense of becoming donors themselves. The idea of human dignity is possibly the most important part of the whole Bóthar system. A little more detail about how the cows and goats are cared for in an African project: 28. Housing for cows and goats. All families must construct a proper shelter for their animal before it will be handed over. These shelters are called zero-grazing units and are made from locally-available materials – sticks and grass. The Irish animals are not allowed to wander around with the native African goats and cows – not because we want to be unfriendly, but because they would catch diseases they would not be used to and would die. Particularly a disease called East Coast Fever that they get from a little tick, an insect that lives in the grass and would jump up on the animal and bite its skin and suck the blood, giving them the disease. Instead they live in the zero-grazing units, as they are doing no grazing. Also, if they were left out they might get lost or stolen and they need to be protected from the strong sunlight. 29. This zero-grazing unit is for a goat. They are always raised up from the ground for a couple of reasons: firstly so that the animal will be able to lie down without getting wet in the rainy season – this could cause pneumonia; secondly, so that any manure or droppings will fall through the floor where they may be collected by the family; just like in Ireland they are then spread on the land to help fertilise the crops and vegetables. In some places, such as Uganda, many families have been able to invest in a domestic biogas plant, where cows’ manure is fed into a special biomass digester, which, through a process of fermentation produces methane. This is piped into the house where it provides a very good gas flame, used both for cooking on specially made ring stoves, and for lighting by means of a gas mantle. One cow can provide an adequate supply for the family and this in turn gives a much healthier way of cooking and saves many trees from being felled for firewood. Once it is finished, the spent manure then passes into another chamber and is taken out for use on the land. It then breaks down more efficiently than if it had not had the methane extracted. The importance of manure from these animals is often not fully appreciated by us in this part of the world, where application of artificial fertilisers is widespread. In developing countries much of the land becomes exhausted from constant sowing of heavy crops such as maize, without any access to fertiliser of any kind. Cow manure is a very rich source of nutrition and can restore a domestic vegetable plot to a high level of productivity. Families are also taught the importance and practice of composting using a variety of methods. A note about families: look at the lady in this picture. How many children has she got? Five young children – a lot of people to feed every day. You can see why the animals are so important to them – they feel as if they have won the lottery! Who is missing from the photo? Very often the families we help will be missing either the mother or the father, for a couple of reasons: if there had been a war, e.g. in Rwanda, the father might have been killed. More often, the cause is disease. What are the two main diseases that kill people in Africa? (Often students will know HIV/AIDS and malaria.) Sometimes both parents are dead and you can have large families being looked after by a grandparent or by uncles or aunts who may have many children themselves. Sometimes it is even the eldest child who has to try and care for all their siblings by themselves – the phenomenon known as Child-Headed Households, which is all too common in Africa. The animal will make a huge difference to them, perhaps even the difference between life and death, as, indeed, many goats made that very difference to Irish people during the Famine. Contrast this to our own situation – if we received a goat we might find it a nice addition to the family, but it would not radically alter our lives. 30. Fodder. In many dairy cow or dairy goat programmes, Elephant grass or Napier grass is often grown beside the family home and next to the zerograzing unit. This grows very well and quickly in Africa. If allowed, it grows to the size of a small tree, 5-7 metres. It is usually cut at about 2 metres. They will also grow legumes, etc. for protein, depending on the area. 31. Benefits to the family. 32. What will your support do? Students will be able to list most of these off. 33. Website address. Ends. Sep 2010