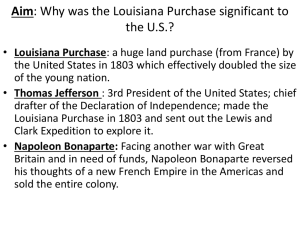

The Louisiana Purchase

advertisement

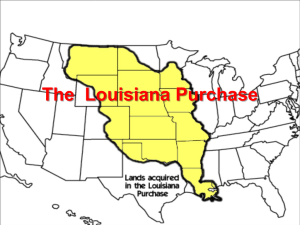

The Louisiana Purchase After the Revolutionary War, Americans started to move “west.” To the people of that time period, this meant going west of the Appalachians. The Mississippi River was the western boundary of the United States. Spain controlled the land on the other side of the river in the late 1700s. Some Americans crossed the river anyway and began living and working there, which bothered Spain. The Spanish did not have the money or army in North America to stop new settlers and thought that eventually America may take over the western lands if enough settlers were allowed to stay. The Mississippi River was also controlled by Spain and was a major transportation route for the farmers and traders living in that part of the country. Many major rivers, such as the Tennessee, the Ohio, and the Missouri ran into the Mississippi. Products were loaded on boats and brought down the rivers to the Mississippi River and on to the port of New Orleans. There, larger boats would be waiting to venture into the Gulf of Mexico and onward to the Atlantic trade routes. When Spain began fearing an American take over, they closed the port of New Orleans, stopping trade completely. Then, in 1800, Spain negotiated a deal with France, giving the land west of the Mississippi and control of the port of New Orleans to the French. This scared the American farmers because Napoleon, the French ruler, was powerful and could stop the westward movement and trade of American settlers. Napoleon had conquered most of Europe at this time and had control of Santa Domingue (now Haiti) in the Caribbean, also. This island was run by plantation lords who used black slave labor to grow sugar cane. Cane was processed into molasses and rum, very profitable exports for France. Napoleon thought the new land west of the Mississippi would be good for growing food to feed these slaves. What he did not anticipate was a rebellion by the slaves. Busy fighting in Europe, the French could not stop the uprising in the Caribbean. In 1802 the blacks gained their independence from France. Napoleon no longer needed the land in North America. What he needed was money to continue his fighting of the British in Europe. This was a very fortunate turn of events for America. Thomas Jefferson was president of the U.S. and knew the French well, having lived there for years as an American ambassador. He saw an opportunity to get control of the port of New Orleans and sent an ambassador with an offer to buy it. Napoleon instead offered to sell all of the land he controlled west of the Mississippi, an area called “Louisiana,” including the whole Mississippi River and the port of New Orleans. His asking price was $15 million, or just about three cents per acre. It was the deal of the century and Jefferson knew it. However, there was a problem. The Constitution did not say anything about allowing the purchase of foreign lands with public money. Jefferson was very strict in his own interpretation of the Constitution and would have to go against a personal belief in order to allow this deal to happen. He asked, “Was this purchase unconstitutional?” After some debate and with the approval of Congress, the Louisiana Purchase was made in 1803, doubling the size of the United States of America. The land of Louisiana was largely unexplored; some believed it would be a desert wasteland. Jefferson hoped it would be a treasure and immediately arranged for a “Corps of Discovery” to go exploring. At the very least, the U.S.A. had control of the Mississippi and trade resumed, bringing adventuresome Americans into the agricultural heartland that today we call, “the bread basket of the world.”