Acute onset jaundice

advertisement

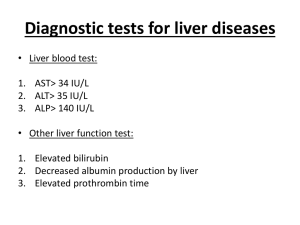

Block 8 Week 3 Acute onset jaundice Tutor : Prof DF Wittenberg MD FCP(SA) dwittenb@medic.up.ac.za Objectives: To be able to list the causes and discuss the investigation of patients presenting with acute onset of jaundice know and discuss the epidemiology, aetiology, pathogenesis, pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnosis, complications and detailed management of patients suffering from acute hepatitis Illustrative Case Report Case 5: AM, a 5 year old girl, presents to the hospital with jaundice of recent onset. According to the grandmother, she has not been well for some time, although there have been no specific complaints. About a week ago, she started to complain of abdominal pain and intermittent vomiting. She had no diarrhoea. From one day ago, she has developed a yellow discoloration of her eyes and skin. Today, she has passed a stool which was tinged with red blood. She is now lethargic and cannot walk in a straight line. On clinical examination, she has a fever of 38.5’C and looks acutely ill. She is deeply jaundiced. Generalised lymphadenopathy is present in neck, axillae and groins. She is moderately dehydrated, and also has mild pedal oedema. Her pulse rate is 160/ minute and the respiration rate is 60/minute. On abdominal examination, she has generalized tenderness, maximal over the liver. The liver is enlarged 6 cm in the midclavicular line, firm and tender. The upper border of the liver is percussed in the normal position. There is shifting dullness, and the spleen is just palpable. Apart from the tachypnoea, there are no abnormalities identified on auscultation of the lungs. A presumptive diagnosis was made and treatment started, but the patient deteriorated over the course of the next few days and died. Introduction Jaundice refers to a yellowish discoloration of the sclera and is seen with an accumulation of bilirubin in the blood. Task: Where does bilirubin come from? Review the production and metabolism of bilirubin Hyperbilirubinaemia is of 2 types: Unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia suggests excess production of bilirubin, as seen in haemolysis, or an inability of the liver cell to take up or to conjugate the bilirubin. Examples of such a type of jaundice are seen in o Malaria : massive destruction of red cells by parasites o Septicaemia o Haemolytic crises of congenital haemolytic anaemia o Acquired forms of haemolytic anaemia eg auto-immune o Congenital conditions eg Gilberts disease, Crigler-Najjar syndrome Conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia occurs when there is failure by the liver to completely clear the bilirubin from the blood stream o Liver cell dysfunction : Hepatic cell damage (hepatitis) or necrosis o Bile flow obstruction Task: Review the causes of hepatitis (Coovadia & Wittenberg p 583) Management of acute onset jaundice This includes the following key aspects: 1. History Previous health ? Acute infective hepatitis usually occurs in previously healthy individuals. Toxic or drug induced hepatitis follows an identifiable episode/drug administration, often given for a particular illness. Acute liver failure and septicaemia is associated with shocklike states and progressive disease. 2. Clinical examination Clinical state ? In acute infective hepatitis, the jaundice occurs in a generally well patient, with the exception of some liver tenderness. The seriously ill patient with confusion or coma is likely to be in hepatic failure or may be septicaemic. Examination of the liver ? Patients with very big, firm or hard or irregular livers generally have a pre-existing condition involving the liver (chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, systemic disease involving the liver). The liver of acute hepatitis is generally mildly enlarged and somewhat tender. A small or shrinking liver is indicative of liver necrosis and acute failure. 3. Investigation Urine: If a freshly passed sample of urine is shaken to produce surface froth, this will be yellow in cases of true jaundice (versus disoloured sclerae). The colour is dark, bilirubin is present once the serum level of bilirubin is high. Urobilin is found particularly when there is excess bile pigment production (haemolysis) and stercobilin is reabsorbed from the gut. Serum bilirubin is elevated and the presence of conjugated bilirubin points to involvement of the liver. Elevation of the liver enzymes points to cell damage. Involvement of the various types of cells is reflected in differing elevations of the different enzymes. The degree of enzyme elevation is not related to the degree of damage; indeed, the enzyme levels can rapidly drop in cases of severe fulminating liver cell necrosis. The following are tests of liver function: Tests of synthetic ability: Serum albumen, prothrombin index Tests of detoxification/conjugation : Serum ammonia, serum urea Tests of excretion/ bile production : serum bilirubin and conjugated bilirubin Maintenance of fasting blood glucose Integrity of liver cells : enzyme levels The above tests will be able to tell that liver damage is present and whether liver failure has occurred, but not what is causing it. It is not enough to know that the liver is involved, ie that hepatitis is present. Tests of aetiology are also required. These depend on the assessment of the whole case, but in general we will wish to know whether a patient has infection with hepatitis A or B or something else. Case analysis : AM This 5 year old girl has been unwell “for some time” before the onset of abdominal symptoms and jaundice. Abdominal pain, vomiting and jaundice within the last week points to a recent insult of the liver. The liver may be tender in acute hepatitis because of the swelling that occurs due to inflammatory cell infiltration. However, in acute hepatitis the liver is usually only slightly enlarged and not firm. This child’s liver is 6 cm enlarged, suggesting that there is another cause for hepatomegaly than just an acute infective insult. The patient has become confused and cannot walk in a straight line. This suggests the complication of hepatic encephalopathy. There has been bleeding into the gut. This is further support for the possibility of liver failure with an inability to manufacture the vitamin K dependent clotting factors. She also has some oedema, which may point to hypoalbuminaemia. She has generalised lymphadenopathy. This is a finding which does not fit with hepatitis alone. She has to have a more generalised problem which has caused “unwellness” for some time. The patient’s problem is therefore : Underlying disease causing generalised lymphadenopathy and hepatomegaly Progressive liver failure Investigations: Chest XRay : Brochopneumonia changes with reticulonodular pattern Urine : Bilirubin 3+ Serum Biochemistry: S-Albumen 16 g/l (N 39 – 50) INR 4.1 ( N 1) PTT 110 seconds (N 26 – 36 secs) S-Bilirubin 211 umol/l Conj Bilirubin 183 umol/l Enzymes : ALP 111 (N 96 – 297) S-GGT 77 (N 0 – 34) S-ALT 288 (N6 – 32) S-AST 390 (N9 – 34) S-LD 983 (N 10 – 295) S – NH3 83 ( N 21 - 50) P-Glucose 1.9 (N 3.9 – 5.8) Virus serology : Hep A negative Hep B negative The above tests confirmed liver cell damage and functional liver failure and that this was not due to an acute virus hepatitis. Despite treatment, she died a few days later. At autopsy, she was found to have miliary tuberculosis with superimposed centrilobular hepatic necrosis. Task: Study the approach to acute onset jaundice (C&W 579 – 580) and acute hepatitis (C&W p 582 – 588) Objectives: To be able to list the causes and discuss the investigation of patients presenting with hepatomegaly and/or hepatosplenomegaly list the causes and discuss the principles of investigation and management of patients suffering from chronic liver disease and portal hypertension Illustrative Case Report Case 2, page 60 : O.N. ON, a 9 year old girl, has a complaint of gradually progressive abdominal distension. This has been present for at least 2 years. It is now so bad that she has difficulty lying down on a flat bed, and becomes short of breath with exertion. She cannot play with her friends anymore. She has had a few episodes of epistaxis, and her stools have also been seen to be tinged with bright blood. There is no history of any disease. She has not been jaundiced. Her urine and stools are apparently normal. On examination, she is a thin girl with gross abdominal distension. She is not jaundiced. She is fully conscious and cooperative. There are no signs of hepatic decompensation. There is no lymphadenopathy. She has moderate pedal oedema. Some veins are visible on her abdomen; these are evident between the upper abdomen and lower chest and the flow seems to be from abdomen to chest. Abdominal examination reveals a very large firm liver. This is firm in consistency. The spleen is not palpable, but there is a large amount of ascites making palpation difficult. Apart from the discomfort of tense abdominal distension, there is no pain, tenderness or rebound on abdominal examination. There are no haemorrhoids on rectal examination. Her heart and lungs are normal on examination. There is no pulsus paradoxus and her blood pressure is normal. Blood tests show a normal serum albumen and normal liver function tests. The enzymes are normal. Introduction In order to be able to decide that a patient has hepatomegaly, one needs to know the range of normal sizes at different ages. The liver’s position in the abdomen is dependent on its relationships with the diaphragm and the lung above it. A paralysed diaphragm on the right hand side means that the liver is not splinted downwards by the contraction of the diaphragm and therefore moves higher into the chest. In such a case, the liver may not be well felt even though it could be significantly enlarged. This can also happen if there is collapse of a segment of the right lung, again pulling the diaphragm higher up into the chest than normal. A lung which is overfilled with air (air trapping) tends to push the diaphragm down, therefore pushing the liver further into the abdomen than normal. In such a case the lower margin of the liver may be palpated much further down than expected, giving the impression of liver enlargement. This happens in cases of asthma, bronchiolitis, air trapping with mucus plugging or foreign body. It follows therefore that the determination of the upper border of the liver is an essential part of the examination of the liver size. This is done by percussion of the chest downward from resonant to dull in the midclavicular line opposite the 9th costal cartilage. The bottom margin is then similarly identified by palpation or percussion, and the distance between the two points is the perpendicular width of the liver, the Liver Span. This varies by age : 5 cm at 1 week 6 - 7 cm at 8 years It is normal to be able to palpate the lower edge of the liver in children. In the first 6 months of life, the liver may be palpated up to 3,5 cm below the rib margin, thereafter 2 cm is usual. However, the span is much the better assessment of true liver size. Causes of hepatomegaly It is useful to consider the normal liver architecture, list the causes of enlargement or hyperplasia for each cell type or structure, and then list abnormal cells or structures which might be involved: Hepatocytes : Infiltration or storage with Fat - Fatty change Malnutrition, metabolic, toxic diseases - lipid storage Mucopolysaccharides Glycogen – Glycogen storage disease Amyloid protein - Amyloidosis Mineral - Copper, Iron Hepatocyte invasion with virus – CMV, EBV, Hep B and A Abnormal hepatocyte proliferation - cirrhosis Blood cells : Reticulo-endothelial cells : Congestion and damming up of blood Congestive cardiac failure veno-occlusive disease constrictive pericarditis Abnormal accumulations Extramedullary haemopoiesis Generalised RES hyperplasia HIV, Auto-immunity Inflammatory cell infiltration Hepatitis Fibrosis and cirrhosis Granulomata Malignant infiltration Leukaemia Abnormal cells/conditions: Metastases Abscesses Cysts Causes of hepatosplenomegaly In general, these can be seen in one of the following categories: 1) The same pathogenetic process happening in liver and spleen at the same time: Look for a generalised disorder Reticulo-endothelial hyperplasia Infiltration with the same type of cells Leukaemia Gaucher/Niemann-Pick etc Inflammatory cells and granulomata eg TB 2) Disease of the liver with splenomegaly secondary to portal Hypertension: look for evidence of liver disease/dysfunction Cirrhosis and chronic liver disease Hepatic fibrosis and portal hypertension 3) Portal hypertension without significant liver disease Hepatic or Portal vein obstruction Look for evidence of portal hypertension 4) Disease involving predominantly spleen Removal of damaged red cells Malaria Haemolytic anaemia Look for evidence of haemolysis Case analysis : This girl has the following problems: Gross liver enlargement Gross ascites History of bleeding The bleeding could be caused by either liver dysfunction with diminished clotting factor synthesis, or alternatively portal hypertension with bleeding varices. In view of the normal results on albumen and liver function tests, the second explanation is more likely. A paracentesis of the abdomen would be expected to yield a transudate without inflammatory cells and with a low protein content. In that case, the ascites is not due to peritonitis, but is due to increased hydrostatic oncotic pressure secondary to portal hypertension. The patient has a very big liver with normal liver function tests and enzyme values. This rules out hepatitis. A big liver with associated ascites on the basis of increased hydrostatic pressure is found in obstruction to venous return from the liver (Veno-occlusive disease, Budd Chiari syndrome of hepatic vein obstruction, inferior vena cava obstruction or constrictive pericarditis). She does not have the clinical signs of constrictive pericarditis. A clinical diagnosis of veno-occlusive disease is made. A radiological contrast study of the inferior vena cava demonstrated complete obstruction of the hepatic vein. No venous drainage from the liver caused massive congestive hepatomegaly and portal hypertension. Task Study the approach to hepatomegaly, chronic liver disease and portal hypertension (C & W p 581 – 592)