ICspr11 - Icarus Home

advertisement

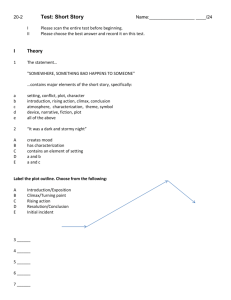

If you haven’t been to a meeting for a while how about coming on April 14th? You’d be most welcome! 6, Knightwood Close Reigate, Surrey RH2 8BE 01737 221814 stevechairman@icarusba.org.uk stephen@wand.fsworld.co.uk ICARUS NEWSLETTER Spring 2011 Website http://www.icarusba.org.uk We send our condolences to the families of the following absent friends: Alan Biltcliffe Barbara Harmer Paul Hodgson Eric Keevy Peter McKeown Colin McLeod Peter Middleton Fred Openshaw Ray Piercey Dave Pink George Roberts Paul Rowbottom It is a shame that Peter Middleton did not live to see the forthcoming marriage of his granddaughter Catherine. He received a fine obituary in The Times, on November 27th 2010 which can be found later in the newsletter. Sadly Barbara Harmer, the only woman to fly the British Concorde, lost her battle against a long illness and died on 20th February. She also received a fine obituary in the Times which can also be found at the end of the newsletter Those of us who were fortunate enough to be at Airtours in the early years greatly miss Pete McKeown, who gained the respect and loyalty of us all whilst he led the Airtours team. The first picture shows Captain Peter in Lufthansa uniform whilst opening up their routes for them. The second photograph shows PJ addressing those present at the Airtours 40th anniversary lunch at Brooklands, on 6th March 2010. A copy of the eulogy given by John Mason at Peter’s funeral service is also appended to this newsletter. The death of David Pink happened in unfortunate circumstances. He was walking in the Drakensberg Mountains in SA with his wife and a guide in early February when the weather deteriorated and he was struck by lightning before they could reach a refuge. He sadly died four days later. People News It was good to hear from Chris Spurrier. I noticed that he had written a poignant article which will bring back memories of bad days in the “office” as co-pilots! It was published in Guild News and Chris has kindly agreed for me to reproduce the piece here for those of you that do not subscribe to that publication. It is called “I learnt about flying from that”: “I am sitting in the right-hand seat of a VC10 on the way to Addis Ababa and the events that occur are most unusual and more than somewhat interesting! Esteemed Commander (E.C.) is on his first trip postcommand course and the aeroplane is going to the Seychelles, via Addis. I am looking forward to a couple of days in each place (those were the days!). Addis in the 1970s is a rather nice place and a good time can be had by one and all. I am somewhat friendly with the station manager and there are a couple of pounds of best cheddar in my suitcase for his son, who has a craving for the stuff. This, it is to be hoped, will see a few beers float our way, sometime after landing. Then there is a rather nice restaurant called The Cottage where the waitresses are particularly sinuous Nubians, who wiggle in a most enticing manner. I was there only a couple of weeks back and the prospect of another evening at The Cottage is filling me with a rosy sort of glow and in fact all is pretty good with the world. Or at least it is until abeam Khartoum, when our engineering consultant announces that we ought to shut down number 4 engine. There is not a lot of drama to shutting down an engine on a VC10 so we do that and our esteemed commander puts on his best pensive mode. Spare engines are thin on the ground at Addis but there is one in Nairobi, this being the time that BOAC scattered spare engines around the world for situations like this. Moreover Addis, being hot and high with a short runway is not the place from which to contemplate a threeengine ferry. So E.C. announces that we are continuing to Nairobi (NBO) – good decision so far! NBO isn’t actually our alternate but we can probably get there all right so frantic sums follow (no computer flight plans or INS in these days) so all manual calculations. There are three of us pilots, one doing the navigating with a sextant and lots of complicated stuff like log tables. NBO is about 600 miles further than Addis and HF comms are not very good over Africa so I am doing a great deal of shouting to arrange a reroute. This is all most exciting and I am more or less convinced that all concerned know what is happening as we steam off southwards. What I’ve not mentioned so far is the NBO forecast which says fog for our estimated arrival time. E.C. is a sanguine sort of chap so when I point this out to him he says “Yes I know, but the forecast for NBO always says fog for this time of day at this time of the year”. So we continue south and the sun comes up and we eventually get within VHF range of NBO. They seem surprised to hear from us but we are mostly expecting that. What we are not expecting is to be told to enter the hold as number eight to land because it is foggy! This is definitely not part of the master plan, as we are becoming seriously short of fuel by now; also the pax are beginning to wake up and enquire as to why we are still airborne, rather than sitting on the ground at Addis. Only one thing for it – Kilimanjiro. Kili is quite close, has a long runway, is rarely used and has no fog. So off we go again. This time it all works well and we find ourselves sitting on the ground with 140 pax, a dead aeroplane and a near-deserted airport. This has become a real adventure. We manage to get the terminal opened up and some breakfast sorted out with the cabin crew helping the locals with the service. Meanwhile E.C. is trying to find hotels. There are some, but they are ten miles away and there is only one 30-odd seater bus available – also, there are not enough rooms available! A new career looms for me and the other first officer as we set up a mini accommodation bureau pairing off all the singles to make the rooms spin out. There is an enormous amount of goodwill from the pax considering that they expected to be in Addis and the Seychelles, rather than Kilimanjiro. Anyway, we set off to the hotels after a very long day (night) before overtime payments had been invented. I still have a letter in my log book from a person high-up in cabin services dept thanking me for being a good steward by helping to serve meals on the ground! Minimum rest is taken, after which we are back off to the airfield, minus the pax but with the cabin crew, for a three engine ferry flight to NBO. As I had done some 3-eng ferries in the RAF I am surprised that no one seems to think twice about this and there are no requests for permissions or dispensations as we do the sums. I wrongly assume that the E.C. has done at least one such take off for practice as part of the command course and we just do it. Very interesting it is too at that altitude! With the entire BOAC African schedule now in tatters, we finally deliver our aeroplane to meet its new engine and set off to the hotel, to await flying the serviceable aircraft back to London. No meal in The Cottage, no days in the Seychelles; but I learnt about flying from that! I learnt that when the forecast nearly always says fog it is often because there nearly always is fog. I learnt that if you are going to initiate a long range diversion it is a good idea to have a spare diversion-for-the-diversion up your sleeve. Above all I learnt that flying commercial aeroplanes isn’t just about flying. It is very much about looking after your passengers in unexpected circumstances and taking control of your own destiny when you are somewhere out of the way. Don’t ask – just do it. Finally I learnt that there was someone in the higher echelons of cabin services who thought that pilots came under their control. ****** Mike Bannister has provided some information which will be of interest to those with a soft-spot for the Big White Speed Machine. You will recall the fine picture of Concorde G-BOAF over the Clifton Suspension Bridge in 2003, prior to Les Brodie landing the icon smoothly and accurately at Filton, to complete the very last Concorde flight. Since then it has remained outside, in anticipation of the building of a museum to protect alpha-foxtrot from the elements. Although it has been open for public visits, the revenue generated has become insufficient to cover the day-to-day operating costs, let alone the funding of a museum. A recent BA annual inspection revealed the need to repair leaks and corrosion at various locations around the airframe and a maintenance/preservation programme will be carried out in the Airbus hangar at Filton before the aeroplane is returned to its existing outdoor location but without public access. There will now be a renewed effort by Airbus, BA, The Concorde Trust, members of the Bristol Aero Collection and other interested parties to find a permanent home for the aircraft where she can be displayed and preserved appropriately. The work of the Trident Preservation Society has been brought to my attention by Terry Henderson who was contacted by Neil Lomax, the preserver of Trident 3B G-AWZK, now on display at Manchester Airport. Those who consider the HS 121 Trident 1C to have been a masterpiece of aviation will no doubt want to follow the efforts of the resolute team, including Neil and project leader Tony Jarrett, who intend to move the last remaining complete airframe (G-ARPO) to Sunderland. Papa Oscar was delivered to Teeside Airport (now Durham Tees Valley, formerly Middleton St. George) by Dick Boas in 1983, which was the very last flight of a BA Trident. It resided in the Fire Training area of the airfield but survived complete as it was used for smoke and evacuation purposes, rather than as a bonfire. The intention is to dismantle the airframe into a kit of parts and to transport them to the North East Aircraft Museum for re-assembly. Details are updated regularly on the website www.savethetrident.org which carries the latest project information. Flights to Remember…. (or forget!): Not BOAC/BEA/BA incidents, but a brace of accidents involving three HS748s, thankfully resulting in no significant injuries to those aboard. The 748 or “Budgie” as it was affectionately known by our boys, was a work-horse of our airline’s Highlands and Islands Division, replacing the Viscount, and the type performed well in the demanding Scottish weather conditions and limited airfield infrastructure. These two incidents show that getting things slightly wrong and getting things slightly right are but a whisker apart. It is surprising that there were still several grass airfields in the south of England handling public transport flights in the mid 1960s and these two incidents occurred at two of them - Lympne and Portsmouth - although Lympne did acquire a concrete runway in 1967, as a result of frequent closures due to water-logging. (i) Skyways Coach-Air HS748 G-ARMV 1630hrs, 11th July 1965. The aeroplane was operating a scheduled Beauvais to Lympne, service as part of the Paris to London coach and air integration carrying 2 pilots 2 cabin crew and 48 pax. Lympne, near Hythe in Kent, had three mown grass strips and an SRA approach was available to the r/w 20 strip, with a landing limit of 200ft ceiling and 1100m RVR. The actual weather was given as visibility 1000m in drizzle, cloud base 250ft and wind 220/18 gusting 26kts. The final instrument approach in azimuth, with height per mile advice being given by the Lympne radar controller, commenced at 4 miles from touchdown, when the aircraft was in cloud at 1100ft in turbulence. At half a mile from touchdown when the talk-down finished, the controller advised the pilots that they were lined up with the right hand side of the strip. The remainder of the approach was made visually, but the radar man continued to track the aeroplane and he observed it deviating further to the right of the extended centre line as it neared the touchdown point. The captain subsequently said that he could see the ground from 250ft, and at half a mile out and 220ft, could see the far boundary of the field through heavy drizzle. 220ft was maintained for 3 to 4 seconds and then descent recommenced with full flap and reduced power when the turbulence became severe. The captain realised that the aircraft was going to the right of the strip but decided not to regain the centre line as it would require a turn at a low height. As the airfield boundary was crossed the starboard wing was held down to compensate for the port drift and the airspeed was fluctuating around 88kts, but as he closed the throttles the starboard wing suddenly dropped. Although aware that the aeroplane was descending rapidly, the captain was more concerned at restoring lateral level and only at the last moment did he attempt to reduce the rate of descent. The 748 struck the ground very heavily on its starboard undercarriage, with the impact tearing off the starboard wing, engine and undercarriage leg. The aircraft rolled over to starboard onto its back and slid along the ground inverted, coming to rest having swung through 180 degrees. Fortunately the passengers and crew were able to exit the aeroplane relatively unscathed. Welcome to Lympne! The cause was listed as “a very heavy landing, following an incomplete flare from a steeper than normal approach”. Despite the provision of a concrete runway in 1967 ( still visible on Google Earth) the airfield closed and Skyways was absorbed into Dan-Air in 1972. (ii) Channel Airways HS748s G-ATEK 1248hrs & G-ATEH 1434hrs 15th August 1967 Both aeroplanes were scheduled to arrive within 90 minutes of each other, at Portsmouth’s grass airfield, from Southend and Guernsey respectively and both crews experienced patchy low cloud and rain in the visual circuit. No information was given to the first aircraft’s pilots concerning the wet aerodrome surface conditions and the captain elected to land on the R/W36 strip. Following touchdown the aeroplane initially decelerated, but in the later stages of the ground roll it was apparent that it would not stop in the distance available and it came to rest, seriously damaged, on top of an embankment forming part of the northern airfield boundary. The19 pax and 4 crew used the rear door to evacuate the aircraft. Although the captain attributed this accident to the poor state of the aerodrome surface, the airport manager blamed it on a late, fast touchdown and assessed the aerodrome as serviceable. The second 748 made a partial right hand circuit to the south of the city to land on R/W07 strip. The captain was aware of the poor braking conditions having landed at Portsmouth three hours previously, and was warned by the tower to expect poor braking – he was not, though, advised of the mishap to G-ATEK. He misjudged the first approach and after bouncing a number of times the aircraft took off again for an approach in the same direction following another right hand circuit. After a firm touchdown the aeroplane initially decelerated for the first two thirds of the landing roll but then deceleration became negligible. The aircraft slid until it broke through the perimeter fence, coming to rest on the main road, having sheared off the nose and main wheel legs on a raised banking at the side of the road. A rapid evacuation of the 62 pax and 4 crew was made through the main doors, which were at ground level. Fortunately at the time of the crash there was a break in the usually heavy traffic on this road. Although the actual fuselage of G-ATEH was only slightly damaged in the accident itself extensive damage was inflicted on the rear fuselage by unqualified personnel during efforts to remove the plane from the road before the arrival of an RAF salvage team with proper equipment. Subsequently, in establishing the cause of the accidents, it became evident that the Portsmouth HS748 operation was unsafe at the permitted maximum landing weight whenever the grass was anything other than dry. This situation seemed to have resulted from the omission of necessary landing distance increments by the MoA which should have been applied in wet conditions at grass airfields, based on information calculated following tests in 1962, coincidentally, undertaken at Lympne! It is ironic that the UK authority had recommended to their counterparts in New Zealand that a 30% wet landing increment be applied at NZ grass airfields, whereas they did not call for an increment to be applied similarly in the UK. When such an increment was made mandatory shortly after the accidents the Channel Airway’s Portsmouth 748 operation was terminated as being impractical and uneconomic. The airfield eventually closed in 1973 and is now an industrial and housing estate. Channel Airways ceased operations in 1972. Top left: the first 748 to arrive. Top right: the second arrival. The third picture shows both damaged aircraft on either side of Portsmouth Airport. ****** The other day my wife and I went into town and went into a shop. Working people frequently ask us what we do to make our days interesting. We were only in the shop for about 5 minutes. When we came out, there was a warden writing out a parking ticket. We went up to him and said “Come on man, how about giving a senior citizen a break?” He ignored us and continued writing a ticket. I called him a stupid git. He glared at me and started writing another ticket for having worn tyres. So my wife called him a dick-head. He finished the second ticket and put it on the windscreen, together with the first. Then he started writing a third ticket. This went on for about 20 minutes and, the more we abused him, the more tickets he wrote! Personally, we didn't care. We came into town by bus. We try to have a little fun each day now that we're retired, which is important at our age…………………………….! ****** Several Icarus members were aboard the maiden voyage of Cunard’s latest maritime masterpiece, Queen Elizabeth, to the Canaries. As committee member Steve Leniston was amongst them there was almost a quorum for a mini-Icarus meeting to be held aboard, no doubt in the Golden Lion Pub, where an agreeable pint of Bass can be enjoyed! I also enjoyed a 5-night QE voyage about a month later visiting Amsterdam (overnight stay), Zeebrugge and Cherbourg. Having previously enjoyed time aboard Cunard’s Caronia, QE2, QM2 and QV, I was interested to see how the new ship compared. It was built in record time (6 months) at an Italian yard near Trieste and looks very similar externally to QV, with the same length and width, weighing in at just over 90,000 gross tons. Whereas QV has contemporary decoration throughout the public areas of the ship, QE has an art deco theme, reflecting the former glory of the previous Queen Elizabeth built just before the war. Indeed a fine marquetry panel, designed by Lord Linley and overlooking the main centrepiece of the vessel, features the previous ship in all its glory. One’s accommodation and evening dining arrangements are a function of the price paid for that particular voyage, rather like WT, WT+, C or F on the airlines. Incidentally Cunard doesn’t call a cruise a cruise, it is a voyage, a cabin is a stateroom and a passenger is a guest, all terms that have to be quickly learnt by guest-lecturers! The ship is laced with many bars, cafes and shopping arcades, all designed to generate revenue and the addition of an extra 15% service charge to bills is universally unpopular as is the addition of daily gratuities to shipboard accounts which all mount up on one’s final bill. Entertainment in the evening is generally of a good standard in an impressive theatre rivalling the best West End venue and, on my particular voyage, a welsh comedian and a Beatles tribute band were very good. QE has an excellent gym covering the full width of the vessel overlooking the bow, which can be utilised to combat some of the excesses in the eating areas – I visited the gym, but only because it happened to be my muster station! Personally I enjoy time afloat as I am stimulated by the operation and navigation of a large ship having spent my Hamble days gazing at impressive passenger liners passing up and down Southampton Water. Of course, the manoeuvring is not as impressive as those days, where 3 or 4 tugs accompanied every arrival or departure and the QE2 was really the last big ship to require such assistance. Nowadays the cruise ships can virtually spin around in their own length, using efficient bowthrusters and stern-azipods, whereas QE2 could really only move forward and backwards alone. A captain of QE2 who has become a friend of mine was most amused to know that the vessel was certified to do 18 knots in reverse – he wondered when he was ever likely to use that facility in anger! On the particular voyage that I took last November on QE, the highlights for me were the navigation to Amsterdam and a rendezvous off Cherbourg with a RN Frigate. Ships mooringup at the cruise terminal in Amsterdam, adjacent to the Central Railway Station, enter a lock at Ijmuiden on the North Sea coast to be lowered to the level of the Dutch countryside, before proceeding for about 3 hours along the relatively-narrow Nordsee Canal, into the City basin. It can be quite amusing to see swans adjacent to the ship as she sails slowly along the canal, not to mention the myriad of cyclists using the towpath. 3 days later, in mid-Channel having left Cherbourg for Southampton, the guests aboard QE were treated to an exchange of salutes between herself and the frigate HMS Campbeltown. Captain Chris Wells, QE’s master, is a member of the RNVR which is why the ship flies the blue ensign whilst in port when he is in command, rather than the more-usual red ensign. The warship initially passed along the starboard side in the opposite direction, before executing a speedy 180 degree turn to accelerate and formate alongside, about 400 yards away. She then fired an impressive salvo of (fortunately) blanks from the midships gun, to which QE responded with 3 blasts on what is laughingly-called the ship’s whistle, a veritable misnomer for a horn audible 10 miles away! Although the event took place in darkness the QE’s guests managed some fine photographs for their family albums. All-in-all I enjoyed my time on this new ship, although it amused me to find that, despite all the design and planning that must go into building such a vessel, there were niggling little faults like the shower curtain in the stateroom bathroom not coming far enough down into the shower tray. Also, in the Lido restaurant on deck 9 where most folk eat lunch buffet-style, the trays catch every 10 feet or so as they slide past joints in the serving-counter. Thus any soup or beverages on the tray spill to create a liquid-cocktail, by the time the end of the rail is reached! However I would certainly recommend a voyage aboard this, or any of Cunard’s trio of modern ships, if you feel that a cruise would be your cup-of-tea. My own favourite would be a voyage to the Baltic ports with St Petersburg being the highlight, although when considering such a trip it is worth looking at a smaller vessel, as those ships normally transit the Keil Canal in one direction or the other, whch is interesting in its own right. Incidentally Cunard have recently appointed their first female captain who is Inger Klein Olsen, 43, from the Faroe Islands. She now commands QV, having worked her way up the seniority system since joining in the 1990s. She has had to serve her time – as Mark Twain once observed “The folks at Cunard wouldn’t even appoint Noah himself to command if he hadn’t worked his way up through the ranks.” But in Captain Olsen’s case is she, I wonder, the Master of her ship or the Mistress! ***** Ex-students from the College of Air Training at Hamble are reminded that there is a reunion of former staff and students taking place on Friday May 7th 2011 at the old BAE social club building in the village, to commemorate 51 years since the opening of the college. Contact the organiser, Phil Nelson (p.a.nelson@btinternet.com) if you wish to attend. We welcome the following colleagues, Taff Thomas and Peter Hunt, who have recently joined Icarus. The committee look forward to welcoming you all to the spring meeting at The Concorde Club, Pavilion Suite Thursday 14th April 2011 at 1930hrs. If you arrive early visit the main club building for a meal, snack and/or drink where you will meet several other members who use the facility prior to the meeting, as does the committee! Should you not be able to attend this time, make a note in your diary that the next function will be on Thursday, 13th October 2011 and we’ll hope to see you then. Best Regards, Steve Wand On behalf of the Icarus committee. The eulogy given by Captain John Mason at “PJ’s” cremation service on 28th January 2011: Captain Peter John McKeown I knew Pete McKeown by sight long before I met him – everyone in BEA knew him, I’m sure. I eventually met him at 15.50 on 23rd December 1963. I can be that accurate because my logbook shows I operated a Dusseldorf flight with him on a Comet 4b from Heathrow. What my logbook doesn’t show is that I was late checking in. Peter had gone to Met Briefing and we two First Officers spun a coin for who would sit in the RHS, the loser having to sit on the engineer’s panel. To my delight, I won. When Capt McKeown returned I introduced myself and apologised for being late, explaining that I had been unexpectedly delayed by the amount of pre-Christmas traffic I had encountered. He clearly wasn’t impressed and said, as a final statement, “We know who’s sitting on the panel today, don’t we?” which put me in my place – literally. Having quite properly admonished me, we then had a very pleasant flight and went our separate ways. I could not have imagined the influence he would have on my life. Peter was born on 27th November 1922 in Camden Town – a Cockney, of which he was always proud. I couldn’t initially find information on his education, but I found out at the golf club that he left school at 14 and was an apprentice telephone engineer. He joined the RAF as soon as he was able, even “amending” his age (unsuccessfully) to try and get in early. He was selected for pilot training which took place in Saskatchewan, Canada in 1942/43, flying the Tiger Moth and then the Cessna Crane, a twin-engined aircraft rather like an Anson. His OCU was in Nova Scotia on to Hudsons and he came home in August expecting a posting to a squadron. But no; January 1944 found him on a Wellington conversion course at Nutts Corner, Belfast, but on completion his hoped-for posting to a squadron still did not materialise. Instead in March he was seconded to BOAC and another conversion course on to the Dakota, which he was then to fly for two years as a co-pilot. The routes he flew took him via Gibraltar to the Eastern Med or long flights across the North Sea to Stockholm and Gothenberg, Sweden still being a neutral country. From January 1946 he had been in the European Division of BOAC but in August it became BEA. That same year, with 2,500 hours to his name, he got his Command. He was 23. He duly became a Training Captain and moved on to the Viking and by 1953 was one of the lead pilots in the introduction into service of the Viscount 700, the world’s first jet-powered commercial airliner. Early in 1955 he and 10 or so of his Training Captain colleagues converted on to the Convair 340 in preparation for re-starting Lufthansa. On 1st March he commanded the first Lufthansa flight since 1944, flying Hamburg-Dusseldorf-Frankfurt-Munich and return (6 sectors). The T/Cs remained in Germany for a year, training the German pilots and establishing a rapport with them that was not matched by the TWA pilots who took over the contract. In 2005, when Lufthansa celebrated its 50th Anniversary, Peter and his few remaining colleagues were invited to take part and flew on a repeat of that inaugural flight – but not in the same aircraft, and certainly not with Peter at the controls. He was over the moon with the hospitality and friendship shown to them after all that time. I asked him if anyone was there from TWA and he said “No, and they weren’t invited!” He came back to play his part in the introduction of the Viscount 802, and in January 1959 he was awarded the Queen’s Commendation for Valuable Services in the Air and his Master Air Pilot Certificate from the Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators. The introduction into service of the Comet 4b followed, a major task as BEA moved into the pure jet era, and he remained on it as the most senior non-management Training Captain until 1965 when he was at last given a management role as Senior Training Captain – but on the Viscount, not the Comet. In 1967 our paths crossed for the 2nd time when he flew with me on my Command Check. I wondered how good his memory was, and if he remembered our first meeting, but if he did, and he had a very good memory, he gave no indication. Instead, he gave me a good lesson in how to settle a candidate whose nerves he knew would be jangling a bit before such an important test, and made the whole day a relaxed and happy experience. He moved on to the BAC 111 as STC in 1968, but that didn’t last long before something called BEA Airtours appeared on his horizon. It was at Chartridge, which BEA used for management training, where he had what he said was a chance encounter with Capt Bill Baillie, who had been Deputy Flight Operations Director, but was now the MD of a charter airline that BEA were setting up at Gatwick. Peter insisted that the conversation started because, quite by chance, they were standing in adjacent stalls in the gents’ loo. Capt Baillie asked him if he had thought about applying for the job of Flight Manager, in effect Chief Pilot, but Peter, with his management background only in training, had thought he would not be considered sufficiently qualified. He didn’t take long before saying “Yes, he would like to apply”. This was clearly a huge relief to Bill Baillie as none of the Flight Managers he considered experienced enough wanted to go to a charter outfit at Gatwick but now, by some miracle, Capt Baillie and Airtours had got the right man for the job. The majority of the Captains applying were quite junior but many had flown the Comet as First Officers and were bursting to fly it in command. From this group Peter picked most of his Training Captains and built an airline of real enthusiasts, led by the greatest enthusiast of them all, and I was lucky enough to be one of them. On 6th March 1970 he and his crew operated the 14.00 Palma and BEA Airtours was airborne. Peter was a charming man and an inspirational leader, setting the right tone, expecting the highest standards, giving Captains all the authority they could want and always backing up their decisions that he thought were right and encouraging everyone to use their initiative to keep the operation running. He had excellent relations with the other managers he worked with and with BALPA, too. Above all, he was a very “human” man with a great sense of humour – something he certainly needed from time to time. Over the next few years the Comet was phased out, Airtours converted to B707-436s obtained from BOAC, and began operating world-wide from 1972. On 26th January 1974 he took off on a round-the-world charter flight, returning to Gatwick on 25th February after 14 sectors to 14 countries. In his study are a couple of mementoes of that flight, but the best one by far was a lovely lady passenger called Margaret who became Peter’s 2nd wife, his first wife, Moira, having died some time before. All looked rosy for the future, but that was not to last long. In 1975 a heart problem was detected at his medical and, losing his licence, he had to retire after 33 years and 16,000 hours of flying. He was devastated, but it did not dim his enthusiasm for life. He took up golf and 2 hole-in-one trophies in his study show he occasionally hit good shots. He had joined GAPAN in 1956, becoming a Liveryman ten years later and was elected on to the Court from 1973-76. He had also been initiated into Freemasonry in 1973 and joined Per Caelum, the Guild’s Lodge, in the following year and in Masonic circles was highly respected and active until ill health began to take effect. (PS – I didn’t mention this when I spoke, but in the late 70s Margaret was behaving strangely which the medics assessed as a psychological problem but Peter insisted that they do a CT scan, which revealed a brain tumour, fortunately cured after an operation. Margaret insisted that Peter saved her life, and she was probably right.) He was found to have cancer in the mid-80s and a lung was removed, not entirely successfully, so Margaret found herself looking after Peter more and more, effectively becoming his nurse as well as his wife. Colon cancer followed and was defeated, as he bore the medical problems with the utmost bravery and determination. He lived for 25 years with one lung (and that one only on half power) and succeeded, to a remarkable extent, to live a normal life. Many people would have given up, but that was never his way. He always acknowledged that, without the nursing of his beloved Margaret, with whom he shared 36 years of very happy marriage, he could not have survived as long as he did. His daughter, Linda, who for several years was a Stewardess in Airtours, was always close to his heart and he was very proud of her and his grandson, Grant, who is a talented musician. As time passed, his golfing required a buggy and winter hibernation became the sensible way to avoid infections but even as his health inexorably declined he still was able to attend the Airtours 40th Anniversary Reunion at Brooklands last March, an occasion which gave him as much pleasure as his presence there gave others. Last year, a member of the Golf Society who did not know Peter in his prime said with a voice full of admiration “He’s physically frail now, but he still has a man’s handshake.” And this said so much about Peter in a sentence. He was always able, with a twitch of his RAF moustache and a twinkle in his blue eyes, to charm any lady but equally, he was held in the highest esteem by men, who greatly enjoyed his company and friendship. So it was a very sad time when, on Friday, 21st January, he lost his final battle. Whatever he did, he seemed to make friends and he was a true and faithful friend to us all. He had more influence on my life than any other man, but I am sure he has been an influence for good on all who have been touched by him, and not just the pilots he trained. I have been proud to know him, work for him and call him my friend. I will miss him very much, but so will we all. Thank you, Peter. Goodbye and God Bless Captain Peter Middleton Wartime RAF pilot who, in peacetime, flew for BEA and accompanied the Duke of Edinburgh on a tour of South America. Peter Middleton’s first close encounter with the Royal Family was when he acted as First Officer to the Duke of Edinburgh on a two-month flying tour of South America that Prince Phillip made in 1952. Prince Phillip piloted 49 of the tour’s 62 flights, often with Middleton – who had been specially chosen for the tour by BEA – by his side. Middleton was later sent a letter of thanks and a pair of gold cufflinks from Buckingham Palace. Peter Francis Middleton was born in Leeds in 1920, the third son of Richard Middleton and Olive Lupton, a family of mill owners and solicitors. After early tutoring at home where he developed a love of music and nature, Middleton attended Clifton College, Bristol before gaining a place at Oxford to study English. But within months of his arrival he joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve. He was posted to Canada as a flying instructor and it was two and a half years before he finally saw action, joining 605 Squadron at Manston, Kent in August 1944. Flying Mosquito fighter-bombers, he was detailed to try to tip the wings of German doodlebugs to divert them away from devastating London. As Germany collapsed he was based in Belgium, Holland and Germany itself before being demobbed in 1946. His first post-war job was with the Lancashire Aircraft Corporation. In Leeds he courted and later married Valerie Glassborow, a bank manager’s daughter. He was 6ft 2in tall: she was nearly a foot shorter, vivacious and enjoyed all his jokes. They had four sons. In 1952 Middleton joined BEA and the family moved to Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, where they lived until his retirement in 1974, when they moved to Vernham Dean, Hampshire. On the very last page of his log book, Middleton calculated that he had flown 16,000 hours or five and a half million miles during his career, “or 220 times round the world”. But well before his retirement he had discovered another love; sailing. It had started with the building of small dinghies – the first in the family dining room – that he sailed with his sons on the Thames. In August 1976 he and his wife set sail from the Hamble in their 35ft ketch Nairjaune to cross the Atlantic. They spent Christmas in the Caribbean and then headed for the Bahamas where the following February, ten miles off the coast of the tiny island of Mayaguana, with a terrible crash, they hit a reef. The boat could not be saved and, gathering a few essentials, they set out for shore in their life raft. Landing on a deserted beach, they made themselves comfortable for the night dining off Scotch and ginger biscuits. The following day they found the main town. The Mayaguana people were soon chugging out to examine the broken hull of the Nairjaune and her equipment. The Middletons were invited to visit a local family and found themselves being unabashedly served tea on crockery “borrowed” from their boat. Returning to England, Middleton continued to sail for the next 20 years. His grandchildren recall the best of time being on the boat when they would respond to his every command by crying out “Aye, aye, Kipper”. They never tired of spreading the underside of his toast with peanut butter, which he hated but responded to with theatrical good humour. Middleton had a boundless enthusiasm for life. As well as a keen sailor he was a photographer, writer and carpenter, making tiny tables and chairs for this grandchildren, a pirate ship for them play on in the garden and repairing pews in his local church. His 90th birthday party was attended by the whole family. Middleton’s wife Valerie died in 2006 and he leaves four sons and five grandchildren. Captain Barbara Harmer Apprentice hairdresser who made a remarkable career change to become Britain’s first and only woman Concorde pilot in 1993 In March 1993, at the age of 39, Barbara Harmer flew herself into the annals of aviation when she became the first woman pilot of the supersonic airliner Concorde. She remained the Concorde’s only female pilot to fly regular commercial services in the ten years from then until the world’s only Mach 2 civil jet was withdrawn from service by its two operators, British Airways and Air France, in the wake of a catastrophic accident to an Air France Concorde at Charles de Gaulle Airport, Paris, in July 2000 in which 113 people died in the aircraft and on the ground. An Air France pilot, Béatrice Valle, piloted several flights between the Paris crash and Concorde’s final withdrawal from service in 2003. For Barbara Harmer, becoming a Mach 2 pilot at 60,000ft was a far cry from her first job as a hairdresser in her home town Bognor Regis, a job she stuck at for six years after leaving school at 15. For her, the decision to become a pilot on Concorde was not so much one of those flashes of inspiration that often seize future pilots in extreme youth, as a gradual realisation via several years of resolute application and acquired responsibility — first as an air traffic controller, then as a flying instructor, and later as a commuter airline pilot — that the pilot’s “grail” of Concorde flying might be possible. Of her many memorable experiences transporting celebrity passengers on Concorde, she always rated that of taking the Manchester United football team to confront Bayern Munich in the Champions’ League final in Barcelona in May 1999 as among the most exciting. “I felt quite emotional as I taxied the Concorde out on to the runway with British flags flying and thousands of people wishing the team luck on the way.” Manchester United did not let their Concorde pilot — or themselves — down. They came home with the trophy having scored two goals in injury time after trailing Bayern by a goal for most of the game. After Concorde was withdrawn from service Harmer retrained and became a BA captain on long-haul routes. Barbara Harmer was born in Loughton, Essex, in 1953, the youngest of four daughters of a commercial artist father and a haberdasher mother. Educated at a convent school after the family moved to Bognor Regis, West Sussex, she did well at O level, but as she watched an elder sister struggling unhappily to cope with her A levels she came to the conclusion that this was not for her and left at 15 to become an apprentice hairdresser. She was good at it and for some years felt perfectly happy until it occurred to her that she was becoming stuck in a rut. Although her experience of aeroplanes was at that time non-existent she applied for a job as a trainee air traffic controller at Gatwick airport, at the same time paying for flying lessons, and in due course gaining her private pilot’s licence. At the same time she studied four A levels in her spare time, with an idea of doing a law degree. Her aim at that stage was to transfer to the accident investigation unit, but she found that her employers at the Civil Aviation Authority were not encouraging, imagining that she would want to “settle down”. Feeling that she had hit a brick wall, her thoughts turned to a career as a commercial pilot. She had no means of funding the course for herself (at that time the fees were £40,000) but reasoned that a route into her ambition might well lie through qualifying first as a flying instructor. To get on a course for this required 140 more flying hours than she had at that time, but she patiently amassed them over the next 12 months and, after qualifying, got a job as a flying instructor at Goodwood Flying School. Over the next two years, while she worked there, she also studied by correspondence course and, on a £10,000 bank loan, obtained the necessary air experience. In May 1982 she finally obtained her commercial pilot’s licence. She now had the qualifications. An actual job was more problematical, but after more than 100 applications she found a job at last with a commuter airline on Humberside. After flying with it for 15 months she heard that British Caledonian was recruiting pilots and in March 1984 she was taken on by the airline. Now she was flying the large, wide-bodied, long-haul tri-jet DC10, in addition to the much smaller British BAC 111. The merger of British Caledonian with British Airways in 1987, lamented by some, turned out to be a great opportunity for this now very experienced large- jet commercial pilot. Of the 3,000 pilots employed by BA only 60 were at that time women, but in 1992 she was selected for the intensive six-month conversion course for the pride of the BA fleet: Concorde. Finally, on March 25, 1993, she earned her place in the record books when, as a BA first officer, she piloted Concorde from London’s Heathrow airport to JFK in New York. It was the beginning of a career not only as a top British Airways pilot, but also as an inspiration to women of her generation, much sought for public-speaking engagements. The Mach 2 threehour flights to New York soon became routine, although she never lost the wonder of seeing the world from 60,000ft, while traversing the skies at 1,350mph. After BA suspended its Concordes in the wake of the Paris accident in 2000, she became a pilot on twin-engined Boeing 777s, and qualified as an airline captain. By that time BA had retired its Concorde fleet, in 2003, and she continued to fly long haul as a 777 captain until she took voluntary redundancy from BA in 2009. Barbara Harmer’s life outside flying was as adventurous as that within it. She was a fully qualified commercial offshore yacht master and often commanded the Concorde crew in international yachting events. She had won several races, and, even though she knew she was seriously ill, she had intended to contest a transatlantic event in her French-built 10.5-metre Archambault 35 in 2013. A keen gardener, she had created a Mediterranean-style garden at her home overlooking the sea at Felpham, West Sussex. She is survived by her partner of 25 years, Andrew Hewett, a former police detective inspector and counter terrorism officer. Captain Barbara Harmer, airline pilot, was born on September 14, 1953. She died of cancer on February 20, 2011, aged 57