Deferred Issues on UPA Work Group. Revised

advertisement

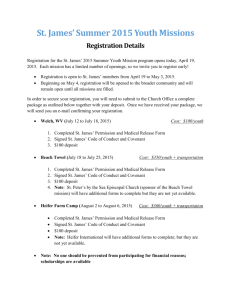

Jeffrey C. Dobbins Lisa Ehlers Executive Director Legal Assistant Wendy Johnson Deputy Director/ General Counsel OREGON LAW COMMISSION MEMORANDUM DATE: June 19, 2008 TO: Oregon Law Commission Program Committee FROM: Kevin Mehrens RE: Project Proposal: Implementation of Uniform Environmental Covenants Act This Project Proposal requests that the Oregon Law Commission’s Program Committee approve the formation of a work group to study and make recommendations on implementing into Oregon law the Uniform Environmental Covenants Act made by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (NCCUSL). The work group would be formed with the goal of producing legislation for the 2009 session. 1. The Problem: The risks associated with properties encumbered by the existence or perceived existence of hazardous materials result in continuing non-use of otherwise viable property. Developers are wary of purchasing lands that may be contaminated with hazardous material. These lands, called brownfields, whether actually contaminated or not, go undeveloped because developers fear the cost of investigating and cleaning the property. The Uniform Environmental Covenants Act (the Act) has two primary goals. The first goal is to “ensure that land use restrictions . . . will be reflected on the land records and effectively enforced over time as a valid real property servitude.” Uniform Environmental Covenants Act, Prefatory Note (available at: http://www.law.upenn.edu/bll/archives/ulc/ueca/2003final.htm) (last visited: April 7, 2008) (hereinafter the Act). The second goal is to “return previously contaminated property . . . to the stream of commerce.” Id. These goals are accomplished by negotiating and recording covenants that run with the land thereby allowing the owners of that property to engage in responsible risk-based cleanups and then transfer or sell the property subject to state-approved controls on its use. The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) already has in place certain incentives for developers considering purchasing contaminated properties. For instance, the DEQ can enter into Prospective Purchaser Agreements (PPA). O.R.S. § 465.327. A PPA is a legally binding contract between the DEQ and a prospective purchaser of contaminated land that limits the prospective purchaser’s liability for contamination, in exchange for a substantial public benefit.1 Id. These PPA’s, however, are contracts between the DEQ and the prospective 1 The statute states that a substantial public benefit can be: “(A) The generation of substantial funding or other resources facilitating remedial measures at the facility in accordance with this section; (B) A commitment to perform substantial remedial measures at the facility in accordance with this section; (C) Productive reuse of a Willamette University College of Law 245 Winter Street SE, Salem, OR 97302 Telephone: (503) 779-1391 Fax:(503) 779-2535 purchaser only. No other parties are bound to them and the benefits and burdens do not run with the land. 2. History of the Reform Efforts The NCCUSL promulgated the Uniform Environmental Covenants Act in 2003. The Act “establishes uniform procedures for the creation, amendment, termination, and enforcement of environmental covenants.” Andrea Ruiz-Esquide, The Uniform Environmental Covenants Act: An Environmental Justice Perspective, 31 ECOLOGY L.Q. 1007, 1008 (2004). Environmental covenants are used to limit potential exposure to contaminants that are left on contaminated properties and provide notice and protection to purchasers of such lands in an effort to encourage their development. There have been many efforts throughout Oregon to create methods for redeveloping brownfields. Among the groups that have endeavored to solve the problems of brownfields are the DEQ through its voluntary cleanup programs and PPAs and the Portland Brownfield Program2. All of these efforts have centered on cleanup and development by a single landowner, in contrast to the Act, which envisions a continuous and binding system for all future owners of the land. The Oregon Legislative Assembly has not yet considered implementing the Act into Oregon law. A task force did meet in October, 2006 to discuss the Act, however, that discussion did not focus on how to implement the revisions in Oregon.3 Therefore, should the Program Committee authorize a work group on the revisions, the work group would have little Oregonspecific groundwork for its efforts. At the same time, however, the work group would not have to work from a blank slate in that 23 states (including the District of Columbia and the Virgin Islands) have adopted the Act4. The experiences of these other states might prove helpful to an Oregon work group. In addition, the Act includes extensive comments to help guide and explain its goals. 3. Scope of the Project Implementation of the Act will not result in any substantive changes to the cleanup standards already in place in Oregon. See, O.R.S. §§ 465.200-.545. Once a site has been cleaned up, whether cleaned under a total cleaning theory or a risk-based approach, the Act “supplies the legal infrastructure for creating and enforcing the environmental covenant under state law.” The Act, Prefatory Note. Oregon allows for a risked based cleanup system for remediation of hazardous sites. O.R.S. § 465(1)(b)(A); see O.A.R. §§ 340-122-0100 to 340-122-0115. The Act intends for covenants to be “implemented only at the end of the decision making process.” Kurt A. Strasser, The Uniform Environmental Covenants Act: Why, How, and Whether, 34 B.C. ENVTL. AFF. L. REV. 533, 551 (2007). This means that after a site has been cleaned to the vacant or abandoned industrial or commercial facility; or (D) Development of a facility by a governmental entity or nonprofit organization to address an important public purpose.” O.R.S. § 465.327(d). 2 The Portland Brownfield Program is a branch of the Portland Bureau of Environmental Services and provides site assessments, clean-up funds and technical assistance for sites throughout the city. 3 See Appendix A for list of invitees to the October, 2006 meeting. 4 In addition, 9 states have introduced legislation in 2008. 2 appropriate level, the covenant is negotiated between the Department of Environmental Quality and the owner of the property and then recorded on the land records. To help delineate the scope of the project, the remainder of this section summarizes the Act by breaking apart each section. Then this memo outlines the existing Oregon law that would be changed by enacting the Act. The sections are as follows: Section 1 – Short Title This section is simply a short title for reference and citation purposes. Many Oregon laws have short titles, some don’t. Inclusion or exclusion of this section will have no effect on the substantive law. Section 2 – Definitions This section lays out 9 definitions applicable to the Act. Under the definition of Agency in subsection (2), the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (the Agency) should be substituted into the brackets. Notable in this section is the definition of environmental covenant. The definition expressly states that the covenant is a servitude. This helps to ensure that the covenant will run with the land and not be considered merely “a personal common law contract between the agency and the owner of the real property at the time the covenant is signed.” The Act, section 2, comment 5. Also noteworthy under the definition of environmental covenant, is that the covenant is created in response to a cleanup project. This means that certain cleanup projects may leave residual contamination.5 The covenant then contains the use restrictions in order to control the remaining risk. See, section 4, infra. Under the definition of environmental response project in sub-section 5(A), the brackets requiring a reference to the Oregon law governing environmental remediation should read: O.R.S. §§ 465.200-.545. This stretch of statutes is the Oregon law regarding hazardous waste and hazardous material removal and remediation. Under sub-section 5(C), the state statute regarding the Oregon voluntary cleanup program is O.R.S. § 465.325. Another important definition is “holder”. A holder is defined as “the grantee of an environmental covenant as specified in Section 3(a).” The Act, Section 2(6). The Agency and the landowner negotiate the identity of the holder. The significance of the holder is that “[a] holder is authorized to enforce the covenant under Section 11. A holder has the rights specified in Section 4 of this Act and may be given additional rights or obligations in the environmental covenant.” The Act, section 2, comment 11; section four is covered infra. Any person can serve as holder, including either the landowner or the DEQ. Section 3 – Nature of Rights; Subordination of Interests This section outlines the rights that the holder of the covenant has as well as the rights of the Agency that is a party to the covenant. The holder is the grantee of a covenant. A holder’s interest is an interest in real property, whereas the agency’s interest, if the agency is not a holder, is not an interest in real property. By making the holder’s interest a real property interest, the drafters help to ensure that the covenant will run with the land. This section also confirms all 5 The level of cleanup required is outlined in O.R.S. § 465.315. 3 “contractual obligations that an agency may assume in” the covenant. The Act, section 3, comment. This means that those obligations are enforceable by “parties adversely affected by any breach.” Id. The Act also deals with the issue of existing mortgages and other prior interests in the property. The traditional rule of first in time, first in right still applies. This means that a covenant entered into with out the approval and subordination of a prior interest is not valid as against that prior interest. To solve this problem, the Act encourages the subrogation of prior interests to the covenant. This means that the Agency can use the prospect of subrogation as a bargaining chip when negotiating the covenant. Prior lien-holders are not required to subordinate their interests, however, there are incentives for them to do so. If a “cleanup and subsequent re-use of the property can be accomplished, the property value will likely increase, thereby increasing the real value of the mortgage as well.” Strasser, 34 B.C. ENVTL. AFF. L. REV., 542. Also, the Agency can insist on subordination of interests when negotiating the covenant, thereby insuring “that that the covenant is not vulnerable to an existing mortgage.” Id. While prior interest holders are not required to subordinate their interests, they will likely want to because the Agency can require that subordination before cleanup efforts begin and require subordination as a prerequisite to signing the covenant. Also, those cleanup efforts will almost certainly increase the value of the property and thus the value of the senior lien-holder’s interest. Section 4 – Contents of Environmental Covenant The Act includes required contents for a covenant and permissive content. Required content >The covenant must expressly state that it is an environmental covenant. >It must contain a legally sufficient description of the property. >It must describe the activity and use restrictions on the property >It must identify and be signed by every holder, the agency and the fee simple owner of the property. >It must identify the name and location of “any administrative record for the environmental response project reflected in the” covenant. Permissive content >Requirements for notice following transfer of interest, applications for building permits or proposals for any site work affecting the contamination of the property. >Requirements for reporting compliance with the covenant >Rights of access to the property >A brief description of the contamination and remedy >Limitations of amendments or termination of the covenant In addition to the required and permissive contents, this section also allows the Agency to require certain parties who have an interest in the property to sign the covenant or else the covenant is not valid. This, as discussed in the prior section, allows the Agency to holdout from entering into a covenant until the prior, or senior, interest holders have signed on to the agreement; thus subordinating those prior interests to the covenant. 4 Section 5 – Validity; Effect on Other Instruments This section is important because it deals with the validity of covenants in relation to traditional common law of property doctrines. The Act makes clear that if the covenant complies with the requirements in the Act, it is valid despite any conflict with existing common law. The Act, section 5(b). The Act states that it is valid even if: (1) it is not appurtenant to an interest in real property, (2) it a can or has been assigned, (3) it is not a character that has traditionally been recognized at common law, (4) it imposes a negative burden, (5) it imposes an affirmative burden on a person having an interest in the real property, (6) the benefit doesn’t touch and concern the land, (7) there is no privity of estate or contract, (8) the holder dies, (9) the owner of an interest subject to the covenant and the holder are the same person. The common law requirements in Oregon for a covenant to run with the land are: “(1) The covenant must touch and concern the land; (2) the original parties to the covenant must intend that the promisor's successors in title be bound; (3) there must be a benefit in the use of the land resulting from performance of the promise; and (4) there must be privity of estate.” Cascade Shopping Center v. United Grocers, Inc., 106 Or. App. 428, 432 (1991). Therefore, covenants formed under the Act could directly conflict with existing Oregon common law. However, as the Act makes clear, an environmental covenant created under the Act, would be valid despite its conflict with existing Oregon common law. It is within the legislature’s authority to change the common law as long as that action does not run afoul of other provisions of the Oregon Constitution. Or. Const. Art. XVIII, § 7; see, 15A Am. Jur. 2d Common Law § 15; see example, Lakin v. Senco Products, Inc., 329 Or. 62, 78 (1999). Since the requirements for a valid covenant do not implicate a substantive right of the people, any legislative modifications to those requirements will not violate the Oregon Constitution. Section 6 – Relationship to Other Land-Use Law This section, as the comment notes, clarifies that the “Act does not displace other restrictions on land use laws, including zoning laws, building codes . . . and the like.” The Act, section 5, comment. In other words, any use, structure or other action that would have been prohibited under the existing planning scheme cannot be made valid through the use of the covenant. The comment in the Act gives two good illustrations of this principle: The Act contemplates that an environmental covenant might, for example, prohibit residential use on a parcel subject to a covenant. Under conventional real property principles, without references to this Act, such a prohibition or restriction in an environmental covenant will be valid even if other real property law, including local zoning, would authorize the use for residential purposes. Alternatively, a covenant might, at the time it is recorded, permit both retail use and industrial use on a vacant parcel of contaminated real property while prohibiting residential use. Assuming all retail and industrial uses were permitted by local zoning at the time the covenant is recorded, the municipality might, before construction begins, change that zoning to bar 5 industrial use. If such a zone change is otherwise valid under state law, nothing in this Act would affect the municipality’s ability to “down zone” the parcel. The Act, section 6, comment. Section 7 – Notice The Act requires that a copy of the covenant be given to: (1) each person that signed the covenant, (2) each person holding an interest in the property, (3) each person in possession of the property, (4) each unit of local government in which the property is located. Id., section 7(a). If, however, notice is not given, this will not invalidate the covenant. Id., section 7(b). The Act contemplates that “the extent and manner of giving notice rests in the discretion of the” DEQ. The Act, section 7, comment. Section 8 – Recording This section requires that the covenant be recorded with the appropriate local body. In Oregon, this is the office where deeds and other devices are recorded in the specific county where the property is located. See, O.R.S. § 554.190; O.R.S. § 554.190. Oregon has a racenotice recording statute; therefore, an unrecorded covenant will not be valid against a subsequent bona fide purchaser for value, who records first. O.R.S. § 93.640. This section is designed for states that have a grantor/grantee index for recording real property interests. Oregon is such a state; therefore, the section can be adopted as is. See, O.R.S. § 205.160. Section 9 – Duration; Amendment by Court Action Covenants under the Act are perpetual unless: (1) they are limited by their terms to a specific duration, (2) they are terminated by a court pursuant to the Act, (3) they are terminated by the foreclosure of a senior interest holder or, (4) they are terminated through an eminent domain proceeding. The Act, section 9(a). A judicial termination is based on the traditional doctrine of changed circumstances.6 There are 2 specific requirements for judicial termination under the doctrine of changed circumstances, first, the Agency must approve of such an action and second, all the parties to the covenant must be given notice of the proceeding. Section 10 – Amendment or Termination by Consent Under this section, the parties are free to amend or terminate the covenant provided all the parties, or their successors in interest, consent to the termination or modification. While this sounds simple, it can, in application, be very difficult to determine whom, exactly, the successors in interest are. In such a case, section 10(a)(3) “provides a judicial mechanism by which the need for absent parties’ consent may be avoided.” The Act, section 10, comment 7. If a court finds that the “person no longer exists or cannot be located or identified with the existence of reasonable diligence” then the court can waive the consent requirement as to that person. Id., section 10. 6 For an example of the doctrine of changed circumstances in the context of real property covenants see, AMJUR COVENANTS § 236. 6 Section 11 – Enforcement of Environmental Covenant This section states that injunctive or other equitable relief is available to any party to the covenant, the municipality in which the property is situated, as well as “any person whose interest in the real property or whose collateral liability may be affected by the alleged violation of the covenant.” Id., section 11. The brackets in subsections (a)(2) and (b) should read: the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality. The basic purpose of this provision is to grant standing “on persons other than the agency and other parties to the covenant because of the important policies underlying compliance with the terms of the covenant.” The Act, section 11, comment 2. While the Act does extend standing to bring a suit to many persons, it does not provide any authority for citizen suits. Other laws, however, may authorize such a suit. The Oregon Administrative Procedures Act (APA), for instance, grants standing to review a rule of an administrative agency to “any person.” O.R.S. § 183.400(1). The question then is what form of agency action is the act of negotiating and entering into a covenant. If it is rulemaking, then the Oregon APA allows for citizen suits. Section 12 – Registry; Substitute Notice This section calls for the creation of a registry for environmental covenants created under the Act. Oregon already has the Environmental Cleanup Site Information Database created by the DEQ pursuant to ORS 465.220. However, this registry is only used for listing the sites themselves and the status of the cleanup efforts. A new registry could be created under the Act. This section includes many bracketed portions that are to be filled in by the State according to their specific rules. If Oregon were to adopt the Act, and particularly this section, subsection (a) should read (with highlighted portions being those specific to Oregon): The Department of Environmental Quality shall establish and maintain a registry that contains all environmental covenants and any amendment or termination of those covenants. The registry may also contain any other information concerning environmental covenants and the real property subject to them which the Department of Environmental Quality considers appropriate. The registry is a public record for purposes of O.R.S. § 192.420. The creation of a new registry is not necessary. The covenants could simply be recorded in the same manner as other interests in property are currently recorded: with the appropriate body of the county in which the land is situated. Section 13 – Uniformity of Application and Construction This section states, in its entirety: “[i]n applying and construing this uniform act, consideration must be given to the need to promote uniformity of the law with respect to its subject matter among states that enact it.” 7 4. Changes to Oregon Law The Oregon common law of servitudes would be changed by the Act, but only with regards to covenants created under the Act. The Act would make no substantive changes to any of Oregon cleanup laws. 5. Law Commission Involvement Due to the environmental nature of the Act, there will likely be interest and comments from individuals and groups across the state. The Oregon Law Commission is well suited to bring these various groups together and work toward a unified proposal that could be introduced to the Legislative Assembly in the 2009 session. In addition, the Act comes from NCCSUL, which makes this a good project for the Commission. Commission Chair Lane Shetterly, a NCCUSL member, has expressed interest in further tying the Commission’s efforts to the NCCUSL’s proposals. This effort would be consistent with the Commission’s operating statutes, which specifically identify NCCUSL recommendations as a subject of the Commission’s law revision agenda. ORS § 173.338(1)(b). Examining the Act would be consistent with the Commission’s statutory charge. While discussion will surely abound surrounding the Act, other states which have adopted the Act have seen support from many environmental groups as well as developers. For example, in Washington, SB 5421 (the Act) had the support of: the Sierra Club, Nature Conservancy, NW Energy Coalition and the Washington Environmental Council, among other environmental groups. 6. Project Participants Commission staff has not to date identified specific individuals in Oregon who might make good work group members for this project. An ideal work group composition, however, would include a mix of developers, environmental and land use attorneys, non-profit environmental groups, representatives of the DEQ and academic professionals who have taught or studied environmental or land use law. Conclusion The Act provides legislation that greatly enhances developers’ ability to make use of underdeveloped land. At the same time, the Act is conscience of environmental concerns. The NCCUSL promulgated the Act to enable these brownfields to reenter the stream of commerce. The Program Committee of the Oregon Law Commission should approve the formation of a work group to study implementation of the Act. By adopting the revisions, Oregon could bring the state’s environmental laws up to date and make them consistent with the laws of a growing number of states. 8 Appendix A: Invitees to October, 2006 Meeting regarding UECA Meeting Invitees Joe Willis Jeff Christensen Charlie Landman Bob Danko David Ashton Jack Munro Ken Sherman Michael Abendhoff Glenn Klein John Ledger Randy Tucker Tom Zelenka John DiLorenzo Susan Grabe Max Miller Kim Stafford Jeffrey Keeney Cyndy Mackey Don Pyle jwillis@schwabe.com CHRISTENSEN.Jeff@deq.state.or.us landman.charles@deq.state.or.us danko.robert@deq.state.or.us David.Ashton@portofportland.com johnmunro1@comcast.net ken@shermlaw.com AbendhMR@bp.com glenn.klein@harrang.com ledger@aoi.org tucker@metro.dst.or.us tzelenka@schn.com johndilorenzo@dwt.com sgrabe@osbar.com max@tonkon.com kims@tonkon.com jeffk@tonkon.com Mackey.cyndy@epa.gov PyleD@LanePowell.com Schwabe, Williamson & Wyatt Oregon DEQ Oregon DEQ Oregon DEQ Port of Portland Lobbyist, Oregon Land Title Ass’n Oregon Bankers Association BP America Inc. Harrang Long Gary Rudnick AOI METRO Schnitzer Group Davis Wright Tremain Oregon State Bar Tonkon Torp LLP Tonkon Torp LLP Tonkon Torp LLP EPA Region 10 Lane Powell Spears Lubersky LLP Call-in Invitees Kenneth Schefski William Breetz Lori Cora Lori Cohen Kelly Cole Schefski.Kenneth@epamail.epa.gov william.breetz@uconn.edu cora.lori@epa.gov cohen.lori@epa.gov cole.kelly@epa.gov EPA UConn School of Law EPA Region 10 EPA Region 10 EPA Region 10 (guessing on email) Addition possible invitees Bernie Bottomly bbottomly@portlandalliance.com 9 Portland Business Alliance