1 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE

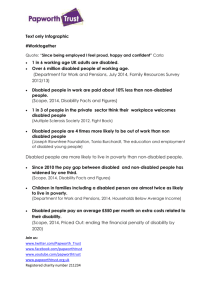

advertisement

Self Perception: How Do Disabled Students Value Themselves? Miro Griffiths University of Liverpool 2 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This attempt could not have been satisfactorily completed without the support and guidance of certain people. In this respect, I wish to express my immense gratitude to my Supervisor, Dr Paul Ziolo, for his constant support over the course of this project. I am also thankful to my Personal Assistant, David Smith, who spent many hours assisting with data collection and other administrative tasks. Additional thanks are extended to every participant who took considerable time out of their busy schedules to contribute to the research, without your involvement there would have been no study. Finally, I would like to acknowledge my partner, Marija Kusulja, who spent day and night encouraging me to undertake this research idea, and motivated me throughout. 3 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? ABSTRACT The social and emotional welfare of young people has, in recent years, been the subject of much research (Crocker and Park 2004); particularly with respect to the impact of idiosyncratic socio-economic circumstance and its significance on the mental welfare, in the context of life-satisfaction and “self-esteem”, of the individual (Shapka and Keating 2005). Within modern society, categorisation is ubiquitous; with divisions based on age, gender and ethnicity perhaps the most pervasive and commonly reproduced social categories. This study, alternatively, focuses on a group primarily defined by intellect, namely individuals currently enrolled on a Higher Education course within the United Kingdom. The reification of this student body is, of course, problematic, since every student possesses a unique biography of personal experience and socio-religious values that generate an almost unique perception of both self and society. Within this study, the group is subject to further division relative to the individual perception of self as either disabled or non-disabled, to allow the critical analysis of quantitaive and qualitative measures of self-esteem and life satisfaction for students placed within the former group (i.e. those with physical impairments), in comparison with those of the latter, and the potential impact of disability on the formation and maintainence of certain negative or positive social ideals. Participation required the completion of a thirty-statement questionnaire focused on self-esteem (Hudson 1982; Pavot and Diener 1993). Each statement was accompanied by a numerical scale upon which the participant was asked to indicate how accurately each statement could be understood to describe their own opinion or represent an accurate description of their own circumstance. Subsequent to the completion of this questionnaire, each participant was subject to a one-on-one interview with the researcher for a maximum of 4 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? 30 minutes, as part of which they were interviewed regarding life-satisfaction and selfesteem in line with those categories of self worth contructed by Crocker and Wolfe (2001). Subsequent analysis of this data evidenced a clear distinction between the scores of the two groups, in line with that explanation offered by Pyszczynski, Solomon, Schimel, Arndt, and Greenberg (2004). Data compiled within the quantitative component of the study were subsequently utilised within a methodological framework centred on Grounded Theory, from which a theory on self-worth was derived. Keywords: Disability, Self-Esteem, Self-Worth, Students, Grounded Theory 5 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? INTRODUCTION There are myriad social circumstances within which individuals are encouraged to publically reflect on their own experience, each necessitated by varying social behaviours; the acquisition and redistribution of information, for instance, or the formation or strengthening of socio-sexual relationships. In this context, personal narratives are primarily constructed around emotionally-significant personal experiences, within which recollection is focused on emotionally- or socially- charged elements at the expense of detail perceived as ‘ordinary’ (Bruner, 1991). While certain details may appear superfluous or uninteresting to the external observer, the importance of the event to self is heavily subjectified by the idiosyncratic experiences of the individual. The psycho-social function of narrative has been examined by Nicolaisen (1991). Within their analysis, post-event interpretation exists as more than a sequential recollection of experience, rather it is filled with structure and meaning which provides an opportunity to duplicate, rehearse and evaluate memory; life-events instil both a temporal and logical order which establishes continuity between the past and present and transforms experience into meaning, or ‘purposeful action of plot’ (see Ochs and Capps, 2001; Taylor, 2001). While there is, arguably, a close conceptual similarity between the two, it is important to make a distinction between ideas of ‘narrative’ and ‘story’, though a categorical terminological boundary is, according to Frank (1995), difficult to determine. Nevertheless, a number of authors have attempted to establish a distinction, for instance Clandinin and Connelly (1998) who consider narration to be a method of inquisition while story depicts the phenomenon of inquiry. This example holds that individual life biographies are worthy of story. A narrative method can be used to describe these biographies, within which data can be collated to formulate multi-component narratives of the experience. As such, the 6 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? consideration of story evolves beyond the simple recollection of a tale, to exist as an opportunity for the construction of social identity (Maines, 1999). One fundamental aspect of the construction and maintenance of social identity is that of perceived value in a socialised context, or ‘self-worth’ (Holstein and Gubrium, 2000). Self-worth can be considered as a complex structure of character traits against which the individual assesses their core component – self-esteem. According to the ‘Contingencies of Self-Worth Model’ or ‘CSWM’ (see Croker and Wolfe, 2001), self-esteem exists as the product of individual ideation, or the need of the individual to possess a similarity to the idealised self. In a critical analysis, Crocker and Wolfe (2001) identified seven categories utilised to evaluate self-worth: family support, competition, physical attractiveness, religious affection, academic achievement, approval from others, and morals. Crocker and Luhtanen (2003) acknowledged how contingencies of self-worth can operate internally (as self-evaluation), externally (as a product of external socio-economic conditions) or as a combination of both inputs. External factors, such as physical attractiveness and family support, tend to correlate negatively with well-being. In extreme cases, this can lead to the development or manifestation of mental-health issues (Jambekar, Quinn and Crocker, 2001), though positive correlation is also evident and demonstrates how emotional anxiety can engender a desire for success in unrelated areas (Baumeister and Vohs, 2001). Contingencies allow an individual to self-regulate their behaviour. To maximise the potential benefit of exploring specific behaviours, the individual must honestly acknowledge failures and weakness, whilst simultaneously developing new adaptive social strategies to overcome them (Crocker, Luhtanen, Cooper and Bouvrette, 2003). Honest self-assessment 7 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? can prove more difficult than one might imagine; to enhance self-esteem, the individual must accept flaws in their character, episodes of personal failure and external criticism of their behaviour. Indeed, Crocker and Nuer (2004) consider that fear of the failure of fundamental self-worth contingencies will result in enormous pressure, stress and widespread apathy on the part of the individual. A noteworthy clarification was proposed by Deci and Ryan (2000) who demonstrate how individuals tend toward confusing the concepts of self-esteem with those of basic human rights; many considering education, the formation of socio-sexual relationships, safety and independence to be of the former rather than of the latter, and as such a context within which their social worth can be augmented. Thus, Crocker and Wolfe (2001) argue, categories derived from the CSWM are of a more fundamental importance than existing as a simple measure of individual self-esteem valuation. Even within a modern, globalised, society, disabled people remain largely marginalised; devoid of human rights, and inhabiting a world designed and constructed by non-disabled people to facilitate the behaviours of a non-disabled society (United Nations General Assembly, 2007). In the United Kingdom, the Prime Minister’s Strategy Unit (2005) has produced a document which outlines those inequalities encountered by British disabled people on a regular basis; a report which demonstrates that a majority of those who fall within this category live in poverty, hold fewer educational qualifications, are generally unemployed, and exist in isolation from what might be understood as the “wider community” whilst simultaneously being the subject of prejudice and abuse. Disappointingly, more recent studies manifest a similar picture of exclusion (Office for National Statistics, 2008). In order to address the issues raised by these statistics, and to correlate them with the work of Crocker and Wolfe (2001), highlighted above, the research question of this paper 8 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? focuses on the perceived self-worth of disabled people. Studies with an analytical focus on both attachment styles and quality of life for disabled people appeared to demonstrate noncorrelation of disability with self-esteem Bunkers (2004), however, suggests that there is empirical evidence that the perceived quality of social relationships had a significant impact on quality of life for disabled people, while Kreuter (2000) examining the influence of disability on social integration, proposes that negativity arising as a result of external antidisability behaviours, results in major issues of social isolation on the part of the recipient. This study was carried out to determine the extent to which disabled students value their lives. While there is little evidence to support the psychological importance of narrative, McLeod (1997) suggests that they convey both meaning and emotional context and a serve to establish or reinforce a sense of self. The present paper attempts to merge qualitative and quantitative data to establish, using primarily data drawn from the former category, the existence, or not, of differing attitudes toward self-worth and self-esteem between disabled and non-disabled participants. A questionnaire was devised which employed a Likert Scale to record the results (see Hudson, 1982; Pavot and Diener, 1993). The hypothesis stated that significantly different attitudes would be displayed by the two groups towards the topic of self worth and self-esteem. The qualitative data discusses the narratives of twenty people (10 disabled and 10 non-disabled), using the contingency factors of the CSWM as a baseline Crocker and Wolfe (2001). 9 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? METHOD Given the methodological approach taken, the design and implementation of this study was divided according to a quantitative/qualitative categorisation. Quantitative Data Participants: Participants were chosen, using a self-selected sampling process, by recruitment through the Announcement Page, located on the University of Liverpool Student Intranet, and the Disability Student Network webpage, located through the University of Liverpool website. Participants were divided into two groups. Group One contained those who defined themselves as disabled. This group consisted of twenty-five participants, with a male to female gender split of twelve to thirteen, all resident in the geographical area of Liverpool or Merseyside, an age range of 18 – 25 years, with a mean of 19.88 years, and a standard deviation of 2.09. Group Two controlled 25 non-disabled participants, with a male to female gender split of twelve to thirteen, again, all located from geographical area of Liverpool or Merseyside. The group age ranged from 18 – 24 years, with a mean of 19.56 and a standard deviation of 1.78 (Appendices A and B). Materials: The questionnaire utilised within this study employed a 1952 Likert Scale, a methodology previously established as the most suitable for investigating attitude using written statement Dittrich, Francis, Hatzinger, Katzenbeisser (2005). The statements used within the questionnaire focused upon themes of self-esteem and self-worth and have previously been piloted elsewhere, with those statements regarding self-esteem derived from Hudson’s (1982) 10 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? questionnaire and those focusing upon self-worth responses developed by Pavot and Diener (1993). Design: The methodological design of quantitative study took the form of a survey, within which the independent variable constituted the two groups, which consisted of two levels; Group One, the allocation of ‘disabled students’ and Group Two, the allocation of ‘non-disabled students’. The dependent variable was the score marks for the two groups. Each participant answered the questionnaire once and could belong only to either group, thereby ensuring that the study utilised a between-subjects strategy. The main control method came in the form of anonymity, with each participant being distinguished only through the attribution of a numerical designation Procedure: Participants were chosen using a self-selected sampling process; each participant witnessed the study advertisement placed either on the Announcement Page of the Student Intranet (University of Liverpool) or through the Disability Student Network webpage, located through the University of Liverpool website (Appendix C). Potential participants met physically with the researcher, upon which, further information regarding the study was provided (Appendix D); once the participant was fully briefed, they were required to complete a consent form (Appendix E), and subsequently undertake the questionnaire (Appendix F). The participant rated their response to each statement by selecting a number which best represented their attitude. The questionnaire was completed in solitary conditions in order to negate the introduction of any perceived socially propitious responses introduced as a product of peer-interaction. Following completion, identification was noted using the 11 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? control method of anonymity and a full debrief provided (Appendix G). Responses collected from the questionnaire were processed through statistical analysis and eventually supported the findings from the qualitative data. Qualitative Data Participants: Similar to the recruitment method utilised for the quantitative data, participants were chosen using a self-selected sampling process, by recruitment through the Announcement Page, located on the University of Liverpool Student Intranet and the Disability Student Network webpage, located through the University of Liverpool website. Of the fifty participants selected for the quantitative research, twenty were selected for interview. Participants were separated into two groups: Group One contained those students who defined themselves as disabled; the group had ten participants, with an equal gender split, all of whom were resident in the geographical area of Liverpool or Merseyside at the time of interview. The group possessed an age range between 18 and 25 years, with a mean of 20.50 and a standard deviation of 2.68. Group Two contained ten non-disabled students, with a male to female gender split of four to six, again, all resident within the geographical area of Liverpool or Merseyside. The group possessed an age range between 18 and 24 years, with a mean of 19.40 and a standard deviation of 2.17. For further information on each interviewed participant, consult Appendix (H). Materials: Interview questions (see Appendix I) were structured around the seven domains outlined in Crocker and Wolfe’s ‘Contingencies of Self-Worth’ (2001). 12 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? Design: Semi-Structured interview was utilised for data collection, a methodology previously established as the most suitable for investigating topical and or personal issues, such as those of self-worth. This format allowed participants complete control over the depiction of their accounts and emphasises the importance of the individual during the process. This technique is highly suited to the collection of qualitative data, while the adherence of the researcher to a program of fairly open questions, and their use of verbal prompts to retain the individual “on task”, contributes an understanding of the psychological responses of the participant (Smith 1995). The process of coding involved four core stages, the first of which was Sentence Coding. This examined single sentences, individually, to identify key words of interest which could be employed in a thematic categorisation (see Miles 1994). The evaluation of single lines ensured that the researcher did not hypothesise, or introduce any personal bias, at this preliminary analytical stage. The second stage, Focussed Coding, collects and categorises repeating themes evident within the dataset. This resulted in the creation of numerous thematic categories formed through those established codes. At the third stage, categories were organised with a focus on the fundamental codes, which would form the basis of the researcher’s theory. The fourth and final stage was Memo-Writing; the transcription of the thoughts of the researcher upon completion of sentence coding and categorisation. It is at this point that theory construction began, as extant patterns of psychological and social process become evident. Memo-writing is the tool with which the researcher defends his theory from critical analysis (Smith 1995). 13 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? It is these four stages of coding which construct the qualitative analytical method known as Grounded Theory (GT) – the product of sociologists Glaser and Strauss in 1967 (see also Charmaz 2007). According to Charmaz (1995), there are six characteristics of GT: integrated data collection and analysis; data-centric coding and analysis; evidence based hypothesis formulation; memo-writing; theoretical sampling used; and delay of literature review. It is important to understand that GT is created on the understanding that categories are formed directly from data interpretation and not from any preconceived hypotheses that would unduly bias the results. There is no preconceived ‘framework of categories’ that would force the emergence, or application, of key themes; instead the approach is deliberately flexible and open, with no obligation to separate data collection from data analysis, unlike other qualitative and theory driven research methods. Procedure: Participants were chosen using a self-selected sampling process; each participant witnessed the study advertisement placed either on the Announcement Page of the Student Intranet (University of Liverpool) or through the Disability Student Network webpage, located through the University of Liverpool website. Participants showing an interest physically met with the researcher, upon which, further information on the study was provided; once the participant fully understood, they were required to complete a consent form, and finally undertake the questionnaire. The participant was then interviewed by the researcher, with questions formulated from Crocker and Wolfe (2001); at all times the participant was encouraged to direct the conversation, with the researcher’s questions used as a prompt for keeping the discussion ‘on topic’. A Dictaphone recorded the interview (Appendix J), and each participant’s discussion was typed verbatim (Appendix K) and eventually analysed through Grounded Theory. 14 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? RESULTS A thirty-statement questionnaire, constructed around themes of self-esteem (see Hudson, 1982) and self-worth (see Pavot and Diener, 1993) was provided to two participant groups, one comprised of physically-disabled, and the other of non-disabled, students, in order to assess any significant variation in attitude. The application of both qualitative and quantitative components necessitated the use of Predictive Analytics Software (PASW) to analyse data collected using these questionnaires. The internal validity of the questionnaire was subject to a reliability test to assess whether a questionnaire improved by the exclusion of certain statements might be utilised in later research to provide further reliable results. Finally, criterion-related validity-testing was carried out to assess the capability of the scale to discriminate between extremes of measured attitude. Mean Standard Deviation Number of scores Disabled 93.60 4.55 30 Non-Disabled 62.63 6.98 30 Table 1. Descriptive Statistics Comparing Total Scores for Questionnaire Data from Disabled and Non-Disabled Participants Mean Score values clearly imply the existence of a difference in attitude between the two groups (Appendix L). Although a criterion-related validity test alone could confirm this, a reliability test remains valuable for gauging the authenticity of the data recorded. 15 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? Reliability Test: Table 2 depicts a summary of the descriptive statistics of recorded data: Mean Item (Statements) Means 2.60 Item Variances 1.61 Inter-Item Correlations 0.14 Table 2. Summary of Descriptive Statistics for Questionnaire Data For scale dimensionality, it is held that a mean inter-item score should read an average of 0.40. Here the mean inter-item value was recorded at 0.14, suggesting a need for item exclusion. Nevertheless, with the statements used here already credited for use in this type of research, the question of reliability surrounding the data lies ultimately with the Cronbach Reading. Cronbach’s Alpha Cronbach’s Alpha Based On Standardised Items Number of Items 0.86 0.83 30 Table 3. Reliability Statistics for Questionnaire Data Cronbach’s Alpha measured the internal consistency of the scale, by comparing the correlation of each item with that of every other. It generally ranges from Zero to One, with one representing complete reliability of scale, within which an appropriate Alpha score is 16 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? considered as 0.70 or higher. Reliability was read as 0.86, making the scale reliable for internal consistency. Criterion Related Validity: Testing was conducted using a one-way ANOVA (Appendix M), with a two-tailed prediction and between-subjects grouping, to determine any variation in attitude between the two groups. The difference in attitude toward self-esteem and self-worth, between disabled and non-disabled groups, was significant: F (1.58) = 415.03, p = 0.001 (two-tailed). The Levene’s Test for Homogeneity of Variance was not significant, p = 0.9, thus the assumption that variance was similar for those samples compared was not violated. To further ensure validity of data, a Brown-Forsythe and Welch Test was carried out alongside the ANOVA; with a significance value of p = 0.001, it was acceptable to reject the null hypothesis. ANALYSIS The research aim, for the quantitative data, was to assess the disparity in attitude toward self-worth between two different groups of students: disabled and non-disabled. Using statistical testing, a significant perceptual difference relating to self-worth became apparent between the two groups. Study of the twenty transcripts within a Grounded Theory analysis revealed an apparent difference in attitude toward particular variables from the CSWM (Crocker and Wolfe, 2001). A theory was proposed to explain the general view that certain contingencies, such as Family Support, Physical Attractiveness and Academic Achievement, were valued contrastingly by the two groups. Nevertheless, other factors from the model, such as Religion, showed a similar perspective between the groups. As such, an interaction diagram was created in order to illustrate these findings: 17 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? Figure 1. Interaction Diagram of CSWM The model illustrated in Figure 1 utilised a researcher’s perspective, thus no consideration is offered to any external approach. It is noteworthy that an initial, independent, assumption may hold certain contingencies to be prioritised, in relation to selfworth, and others held to be irrelevant. Nevertheless, it is at the discretion of the reader to judge this initial view positively or negatively. The actual theory, in its simplest iteration, allows for interpretation as the key factor in the investigation of any such partner view; a fundamental characteristic of Grounded Theory (Allan 2003). As the interview was conducted with a focus on the seven categories constructed by Crocker and Wolfe’s (2001) CSWM, the narrative data recorded fits with those key themes already established. These key themes can be employed in the above model to determine or predict generalised group attitudes and self-worth perspectives. A number of sub-categories became apparent, but, due to analytical constraints which included the practicalities of data recording and the risk of expanding too far beyond the core focus of this research, it was 18 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? decided that analysis would remain concentrated on those five categories displaying attitudinal diversity. Category One: Family Support For this category, attitudes were seen to differ between groups. Responses varied between gratitude and the acknowledgement of familial importance, to despondency and apathy at the opposite end of the analytical spectrum. To cite an example, it was apparent that the disabled participant in T1 perceived his family to be unimportant: “...family, we’re just sort of casual, we don’t have that kind of bonding.” (T1, P1, Line 5) The participant appears well aware of the concept of the socially-stereotyped behaviour of the nuclear family, at least as it relates to bonding behaviours, as he clearly states ‘that kind’; however, he is unconcerned that his family fail to subscribe to the trait. This was similar to another disabled participant’s account: “...don’t really want to engage in what I’m doing by what they think.” (T3, P1, Line 11) This participant clearly references a family uninvolved in her decision-making process; ignoring the possibility that her parents might well possess a greater depth of knowledge and experience that she might access. Explanation may lie in evidently disparate concepts of attachment between groups; attachment processes are complicated by disability, with individuals at increased risk of becoming emotionally and socially maladjusted (see Huebner and Thomas, 1995). With specific reference to the student population, Huebner, Thomas and Berven (1999) proposed that disabled students in America were five times more 19 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? likely than their non-disabled peers, to seek assistance from mental health services, with a majority displaying insecure attachment behaviours. In comparison, a majority of non-disabled participants displayed secure familial attachment which, according to Mikulincer (1995), is demonstrative of greater self-esteem and an increased contentment toward social interaction. One non-disabled participant said: “...it’s gotta’ be the strongest and the most important foundation ever.” (T7, P1, Line 1) According to this participant, familial bonding is seen as a priority in the development of a balanced and healthy lifestyle. In the absence of the strength shared within the family, this participant feels they would not have been able to achieve all that they had so far. In analysing this weakness of attachment between disabled participants and family members, we can look to the work of Kafetsios and Sideridis (2006) who suggest that attachment style is influenced by idiosyncratic perceptions of support and assistance; the likelihood of a negative style on the part of the disabled individual is predisposed, especially when support is ambiguous or family are under stress to provide care; a factor for many families seeking support for their disabled child or young person (Prime Minister’s Strategy Unit, 2005). Category Two: Competition with Others Again, differences were manifest in discussion of competitive behaviours. Of greater note, however, is the manner in which members of the two groups considered the significance of their involvement within a group task: “I would never expect to be singled out for praise.” (T13, P2, Line 27) 20 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? The attitudes embodied within this modest response proved to be generally applicable to all disabled participants. While some would appreciate being singled out, none were motivated by the need for individual recognition and most expected that they would find the experience to be uncomfortable; this latter point raises the possibility that many disabled participants had not experienced this type of situation in the past. According to Crocker, Luhtanen and Bouvrette (2000), competition and school-competency are closely linked achievement-related factors, which are subsumed with the catch-all term of ‘general-approval variables’. As such, competition is regarded by students as a main contingency for self-worth evaluation. For non-disabled students, the general perception was one wherein praise was denied in order to maintain a publically-perceived sense of modesty; though for some, such praise was considered only an appropriate reflection of their own involvement: “Yea, I would (expect it), I am a bit vain.” (T10, P2, Line 20) It is, arguably, easy to understand the causality behind disabled participant perceptions when, with competition closely linked to school competency, statistics demonstrate that 23% of disabled people possess no qualifications, compared to 9% of nondisabled people (Shaw Trust, 2009). This evidence suggests that disabled people fail to utilitise their competitive behavioural skills as efficiently as non-disabled people, including those who have overcome socio-economic barriers to higher education. Category Three: Physical Attractiveness Koch, Mansfield, Thurau and Carey (2005) link sexual desire to the perception of physical attractiveness. As such, it is fundamentally important to consider body image when conceptualising sexual responses, especially in women (see Weaver and Byers, 2006). For 21 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? disabled people, the added consequence of attachment style can affect the perception of attractiveness. According to Prouty, Markowski and Barnes (2000), attractiveness in romantic relationships is assessed by dyadic adjustment; a term which assesses relationship quality by analysing how each partner is influenced by their own functioning. For nondisabled people, the construction of positive relationships and perception of the attractive self is affected by a secure attachment style and dyadic adjustment. Both factors are uncommon in disabled people and many disabled participants were evidently apprehensive in judging their own attractiveness: “I probably wouldn’t say anything; it would make me feel uncomfortable…” (T15, P2, Line 11) To shy away from questioning one’s attractiveness is not a result of disability; many would not publically profess their view for sake of modesty or shame. Indeed, non-disabled participants expressed similar views: “I’m quite shy; it would take me back if someone asked me that.” (T12, P3, Line 3) The general conclusion drawn on the basis of data derived from both groups is that, in general, disabled participants were less comfortable than non-disabled participants in discussing issues of attractiveness. When asked if attractiveness was an integral aspect of self-worth, all participants agreed that it was; the majority of disabled students, however, considered it to have a negative impact: “.. I think it’s a bad thing in a way because [as regards] attractiveness you get what you’ve been given and you’re not being judged on your merit.” (T13, P3, Line 8) 22 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? Within the responses of disabled students a somewhat defensive, and occasionally irritated, perception is manifest; with those responses which adopt a feeling of ‘only getting what you have been given’ perhaps betraying the reasons for their unhappiness. Bureau, deCol, Gruber, Hudson, Jouvent, Mangweth, Pope (2000) proposed, for disabled people, a relationship between body image and behavioural-psychological effects. Data from this study demonstrated that participants overestimated body parts in line with abnormal attitudes toward food and the ingestion of food and a desire to appear thin conform to the perceived somatic ideal as portrayed in the media. This contrasted sharply with non-disabled responses when questioned on the purely physical assessment of attractiveness: “I’m not that bothered but when I go out, I like to look pretty.” (T14, P4, Line 5) It is implicit within the statement that this particular participant considers herself attractive, as is the ease with which she feels she can make this sort of assessment in the absence of independent verification; while she does not bother to ensure she looks pretty at all times, that she does when socialising reinforces the ease with which she assesses her physical attractiveness in a positive way. A study of Western and Westernised school girls (Salazar, Crosby, DiClementre, 2005) noted that, where physical attractiveness was preeminent in finding a friend or sexual partner, those with high levels of self-esteem and self-worth find it easier to communicate their needs and desires, while those with low levels are more likely to engage in promiscuous behaviour, find themselves in vulnerable situations and possess less confidence in finding a partner (Spencer, Zimet, Aalsma and Orr, 2002). 23 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? Category Four: Academic Achievement For many participants, studying at an established university, such as The University of Liverpool, engendered a sense of pride evident in their interview; both groups took satisfaction from studying to university level, though, while disabled students tended to view the fact as an example of what could be achieved, most non-disabled participants considered it largely a ‘means-to-an-end’: “Proud, I see it as a status; I’ve achieved something that I felt I could never get.” (T13, P2, Line 23) This student had faced a number of disability-related obstacles to achieving a university-level education. The disabled participant’s self-worth fluctuated dramatically in conjunction with their received grades and whether they compared favorably with expected results. While this could be explained by perceiving that certain barriers to education might result in disabled student’s self-worth being less contingent on high grades, it could equally be argued that participants had, in fact, over-achieved, relative to the perceived capabilities of a disabled person, and that this influenced their reaction to poor academic results. According to Crocker, Sommers and Luhtanen (2002), those students for whom self-worth is highly contingent on academic study are especially affected by bad grades and manifest larger reduction in self-esteem, greater decrease in positive attitude toward study and a general shift toward disinterest within their chosen field. When questioned over the duration of academically-contingent emotions, negativity, as a product of poor performance, appeared to endure far longer for disabled students compared with their non-disabled peers: 24 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? “I felt, well how am I gonna’ do well if I try my best and still got an average mark? It was demoralising; it lasted for eternity.” (T2, P7, Line 16) Here, the use of the word ‘eternity’ demonstrates the level of emotion triggered by academic performance; with the participant unable to gauge how long his negative perception would last or behave in a manner to remedy it. This intensity was not evident in the responses of the non-disabled participants: “Affects me negatively, short term, but the good thing is that I have an attitude, like let’s move on, there’s nothing I can do about it…” (T10, P3, Line 4) This statement implies that improvements can be made almost immediately to rectify the problem of poor grades; Fleeson (2001) suggest this response is due to highly contingent students adopting avoidance goals in order to overcome failure quickly and focus on obtaining success. This concept does not apply to disabled students, as a lack of egoinvolvement in allowing self-worth to be constructed upon academic achievement negates the possibility of intense positive emotional reactions to the event as a product of low expectation rates beforehand (Kernis, Paradise, Whitaker, Wheatman and Goldman, 2000; Kernis and Waschull, 1995). Category Five: Approval of Others The final category evaluates who participants look to for approval, if, indeed, they look to anyone. There were clear differences between the two groups. This research has already demonstrated that the majority of disabled students possess emotional-attachment issues toward their parents; this fact was borne out again here, where, while mother and 25 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? father proved the primary source of approval for non-disabled participants, the same was not true for the group with impairments: “Teachers, a few of my friends; Yea, I probably need to be approved by others, I don’t like to be too different…” (T8, P4, Line 20) Many selected teachers or academic figures when seeking approval, while those in relationships counted partners as an additional source. The suggestion here is that if a disabled person has poor attachment to their parents and has overcome adversity in order to achieve a high academic status, then it would be a natural step to consider figures implicit in their academic experience as a priority for approval, otherwise their success in this key area could falter (Roberts and Gotlib, 1997). LIMITATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS Using GT, analysis of twenty transcripts illustrated the psychological effects selfworth has on disabled and non-disabled students. Interpretations based on recorded data theorised a disparity in attitudes toward particular contingencies from the CSWM (Crocker and Wolfe, 2001). A theory was submitted explaining how certain contingencies created diverse attitudes between these two particular groups, and why a small number of contingency perspectives might be shared across them. Using the model, (Figure 1), predictions can now be made on understanding the process of self-worth for disabled people, as dependant on particular variables within the CSWM. The model and theory can now be used to determine how certain individuals might respond; however, we must acknowledge that interpretation is fundamental to the identification of the original grounded viewpoint of a relationship between factors. One may 26 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? consider emotional responses to be negative, when others will hold it as a positive and, therefore, alter the perspective. To ensure theoretically effectiveness, there exists a pressing need for theoretical sampling, within which collection of further documentation will inevitability lead to further support and expansion of the developing theory (Cruickshank, 2009). Similarly, limitations must be acknowledged, of which the most significant was the fact that all study measures were self-reported and were therefore susceptible to the social-desirability bias associated with this assessment method. Furthermore, as a product of recruitment methodology, the participant sample may not have been representative; many were of higher educational status, while those within the disabled group possessed only physical impairment and likely constituted a subset more highly socialised than we might expect within the impaired population. If the study was to be repeated for those with learning difficulties or mental health conditions, or disabled people who have been part of disability empowerment network (Alliance for Inclusive Education and Disability Listen Build Include, 2010), from which we would expect increased confidence and ability, results may have been significantly different. As a product of their education, respondents were also more likely to be employed than those disabled individuals with little or no academic qualification. Whether this affects responses provided under the CSWM is speculative. For instance, individuals with more financial resources may be more likely to be involved in a relationship or consider they were more confident and competitive. The sample size here was too small to support further analysis. The practicalities of research dictated that certain elements of spoken language, potentially important for theory construction, were not identified. If these practical issues were overcome, the Jefferson System of Transcription could have been applied, whereby, 27 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? data collection would have included: prosodic, paralinguistic, and extralinguistic components (Cruickshank, 2009). 28 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? BIBLIOGRAPHY Alliance For Inclusive Education and Disability Listen Include Build. (2010). Pushing For Change. Retrieved From: http://www.allfie.org.uk/docs/Pushing%20for%20Change.pdf Baumeister, R. F. and Vohs, K. D. (2001). Narcissism as Addiction to Esteem. Psychological Inquiry, 12, 206-209. Bureau, B., DeCol, C., Gruber, A. J., Hudson, J .I., Jouvent, R., Mangweth, B., and Pope, H. G. (2000). Body Image Perception among Men in Three Countries. American Journal of Psychiatry. 157(8). 1297-1301. Bruner, J. (1991). The Narrative Construction of Reality. Critical Inquiry, 18, 1-21. Charmaz, K. (1995). Grounded Theory. In J. A. Smith, R. Harre, and L. Van Langenhove (Eds.), Rethinking Methods in Psychology (9-26). London: Sage. Charmaz, K., and Bryant, A. (2007). The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory. London: Sage. Clandinin, J. D., and Connelly, M. F. (1998). Personal Experience Methods. in N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 29 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? Crocker, J., and Luhtanen, R. K. (2003). ‘Level of Self-Esteem and Contingencies of SelfWorth: Unique Effects on Academic, Social, and Financial Problems in College Freshmen. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 701-712. Crocker, J., Luhtanen, R. K., Cooper, M. L., and Bouvrette, S. (2003). Contingencies of SelfWorth in College Students: Theory and Measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 894-908. Crocker, J., and Nuer, N. (2004). Do People Need Self-Esteem? Comment on Pyszczynski et al. (2004). Psychological Bulletin, 130, 469-472. Crocker, J., and Park, L.E. (2004). The Costly Pursuit of Self-Esteem. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 392-414. Crocker, J., Sommers, S. R., and Luhtanen, R. K. (2002). Hopes Dashed and Dreams Fulfilled: Contingencies of Self-Worth and Admissions to Graduate School. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 1275–1286. Crocker, J., and Wolfe, C.T. (2001). Contingencies of Self Worth. Psychology Review, 108(3), 593-623. Cruickshank, J. (2009). Qualitative Methods. Essex: Pearson. 30 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? Dittrich, R., Francis, B., Hatzinger, R., and Katzenbeisser, W., (2005). A Paired Comparison Approach for the Analysis of Sets of Likert Scale Responses. Department of Statistics and Mathematics, Wirtschaftsuniversit, Wien. 24. Fleeson, W. (2001). Toward a Structure- and Process-Integrated View of Personality: Traits as Density Distributions of States. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 1011– 1027. Frank, A. W. (1995). The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, and Ethics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Holstein, J. A., and Gubrium, J. F. (2000). The Self We Live By: Narrative Identity in a Postmodern World. New York: Oxford University Press. Hudson, W. W. (1982). The Clinical Measurement Package: A Field Manual. Dorsey Press, Homewood, IL. Huebner, R. A., and Thomas, K. R. (1995). The Relationship between Attachment, Psychopathology and Childhood Disability. Rehabilitation Psychology, 40, 111–124. Huebner, R. A., Thomas, K. R., and Berven, N. L. (1999). Attachment and Interpersonal Characteristics of College Students With and Without Disabilities. Rehabilitation Psychology, 44, 85–103. 31 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? Jambekar, S., Quinn, D. M., and Crocker, J. (2001). Effects of Weight and Achievement Primes on the Self-Esteem of College Women, Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25, 48-56. Kafetsios, K., and Sideridis, G. D. (2006). Attachment, Social Support and Well-Being in Young and Older adults. Journal of Health Psychology, 11, 863–875. Kernis, M. H., and Waschull, S. B. (1995). ‘The Interactive Roles of Stability and Level of Self-Esteem: Research and Theory’. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 27, pp. 93–141). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Kernis, M. H., Paradise, A. W., Whitaker, D. J., Wheatman, S. R., and Goldman, B. N. (2000). ‘Master of One’s Psychological Domain? Not Likely if One’s Self-Esteem is Unstable’. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 1297–1305. Koch, P. B., Mansfield, P. K., Thurau, D., and Carey, M. (2005). ‘‘Feeling Frumpy’’: The Relationships between Body Image and Sexual Response Changes in Midlife Women. Journal of Sex Research, 42, 215–223. Maines, D. (1999). “Information Pools and Racialised Narrative Structures,” Sociological Quarterly, 40, 317-26. McLeod, J. (1997). Narrative and Psychotherapy. London: Sage. 32 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? Mikulincer, M. (1995). Attachment Style and the Mental Representation of the Self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 1203–1215. Miles, M. B., and Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook (2nd Ed). Thousand Oaks: Sage. Nicolaisen, W. F. H. (1991). The Past as Place: Names, Stories and the Remembered Self. Folklore, 102(1), 3-15. Ochs, E., and Capps, L. (2001). Living Narrative: Creating Lives in Everyday Storytelling. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. Office for National Statistics. 2008. Disability and Statistics. Retreived from: http://www.statistics.gov.uk/CCI/nscl.asp?ID=6345 Pavot, W., and Diener, E. (1993). Review of the Satisfaction With Life Scale. Psychological Assessment, 5(2), 164-172. Prime Minister’s Strategy Unit. (2005). Improving Life Chances for Disabled People. Retreived from: http://www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/media/cabinetoffice/strategy/assets/disability.pdf 33 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? Prouty, A. M., Markowski, E. M., and Barnes, H. L. (2000). Using the Dyadic Adjustment Scale in Marital Therapy: An Exploratory Study. The Family Journal: Counselling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 8, 250–257. Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., Schimel, J., Arndt, J., and Greenberg, J. (2004). Why Do People Need Self-Esteem? A Theoretical and Empirical Review. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 435-468. Roberts, J. E., and Gotlib, I. H. (1997). Temporal Variability in Global Self-Esteem and Specific Self-Evaluation as Prospective Predictors of Emotional Distress: Specificity in Predictors and Outcome. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 521–529. Ryan, R., and Deci, E. (2000). Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development and Well-Being. American Psychologist, 55, 68-78. Salazar, L. F., Crosby, R. A., and DiClemente, R.J., (2005). Self-Esteem and Theoretical Mediators of Safer Sex among African American Female Adolescents: Implications for Sexual Risk Reduction Interventions. Health Education Behavioural, 32, 413–427. Shapka, J.E., and Keating, D.P. (2005). Structure and Change in Self-Concept During Adolescence. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 37(2), 83-96. Shaw Trust. 2009. Ability to Work. Retrieved from: http://www.shaw-trust.org.uk/disability_and_employment_statistics 34 SELF PERCEPTION: HOW DO DISABLED STUDENTS VALUE THEMSELVES? Smith, J. A. (1995). Semi-Structured Interviewing and Qualitative Analysis. In J. A. Smith, R. Harre, and L. Van Langenhove (Eds.), Rethinking Methods in Psychology (pp.9-26). London: Sage. Spencer, J. M., Zimet, G. D., Aalsma M. C., and Orr D. P. (2002). Self-Esteem as a Predictor of Initiation of Coitus in Early Adolescents. Paediatrics, 109, 581– 584. Taylor, D. (2001). Tell Me a Story: The Life-Shaping Power of Stories. St. Paul: Bog Walk Press. United Nations General Assembly. (2007). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Retreived from: http://www.un.org/disabilities/default.asp?navid=13&pid=150 Weaver, A. D., and Byers, E. S. (2006). The Relationship between Body Image, Body Mass Index and Exercise and Heterosexual Women’s Sexual Functioning. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 333–339. APPENDICES (See Disc for Appendix Items A – Na)