Business English Collocations: Lexical Approach & Corpus Linguistics

advertisement

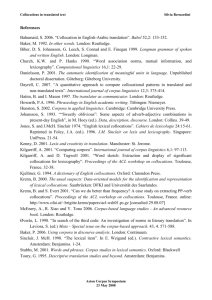

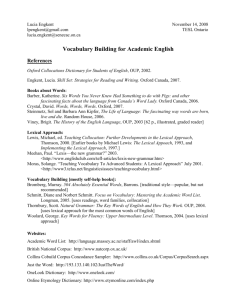

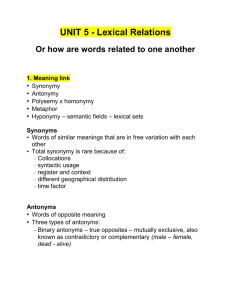

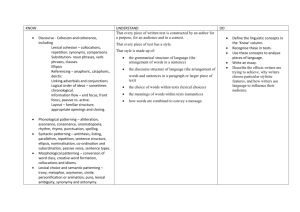

Business English Collocations Drd. Teodora POPESCU-FURNEA Universitatea ” Babeş-Bolyai”, Cluj-Napoca This paper addresses the issue of lexis in the Business English environment. We have tried to analyse the way in which the acquisition of collocational patterns in English may contribute to students’ better functioning in a business setting. We will also present the way in which the English teacher may create his own teaching materials based on the principles of the lexical approach. We will turn our attention to different online resources: the business press, specialist literature, dictionaries, concordancers, and will provide some personal examples of vocabulary exercises which concentrate on collocations. Introduction We will try in this paper to answer two important questions. Firstly, is the lexis of Business English different from that of every day general English, and if yes, how can we best teach it to our business students. The importance of the command of business lexis for business people has been long known and acknowledged. Business English represents one sub-division of ESP (English for Specific Purposes), whose origins may be traced as far back as the Greek and Roman Empires (DudleyEvans & St. John, 1998:1). However, despite the long history of people’s need for specialist knowledge of a foreign language, in order to fulfil pre-set de-limited tasks (business correspondence, travelling abroad, etc.), it is safer to place the ESP movement in the second half of the 20th century. The expansion of ESP is probably the result of two separate but related developments: economic and educational. The rising economic imperialism of the USA has lead to the need to communicate in English, mainly in the language of science and technology. The educational change brought about an emphasis on learner-centeredness, and along with it a change in how language and teaching were viewed. The development of ESP has known several stages. These have been, in turn, Register Analysis, Discourse or Rhetorical Analysis (which later developed the Genre Analysis approach), Needs Analysis, Skills and Strategies; and the Learning-Centred approach. Underlying all these approaches has been the issue whether specific situations where language is used can generate situational or subject-specific language. There has been a consensus, that, while the situations do not engender separate, special language per se, there is a restriction of language choice and a certain amount of specialist lexis. The acquisition of this restricted, specialised language, by both teachers, who need to teach it, and students, has created learning dynamic which is quite different from that of general English. The lexical approach This new approach to language challenges the traditional view according to which language is divided into grammar (structure) and vocabulary (words). “Instead, the Lexical Approach argues that language consists of chunks which, when combined, produce continuous coherent text.” (Lewis, 1997:7) Michael Lewis defines the lexical approach as follows: ... the Lexical Approach places communication of meaning at the heart of language and language learning. This leads to an emphasis on the main carrier of meaning, vocabulary. The concept of a large vocabulary is extended from words to lexis, but the essential idea is that fluency is based on the acquisition of a large store of fixed and semi-fixed pre-fabricated items, which are available as the foundation for any linguistic novelty or creativity. (Lewis 1997:15) According to the same author, language chunks are of different kinds, and he identifies four main types: a) Words: a. stand-alone words (lexical items, words where a single substitution produces a totally new meaning) b. multi-word items (by the way, on the other hand) b) Collocations: words co-occurring in natural text with greater than random frequency. They may range from fully fixed (a broken home) through relatively fixed, to totally new. c) Fixed expressions (social greetings – Good morning, Happy New Year, politeness phrases No, thank you, I’m fine, ‘Phrase Book’ language - Can you tell me the way to ………….., please?, idioms - You’re making a mountain out of a molehill) d) Semi-fixed expressions (almost fixed expressions – It’s/that’s not my fault, spoken sentences with a simple slot – Could you pass ……….., please?, expressions with a slot which must be filled with a particular kind of slot-filler – Hello. Nice to see you. I haven’t seen you + time expression [for/since], sentence heads – What was really interesting / surprising / annoying was …, more extended frames such as those for a formal letter or the opening paragraph of an academic paper – In this paper I wish to suggest a third position…) (adapted from Lewis, 1997:7-11) Collocations We will try in the following to concentrate on the issue of collocation, and its relevance for the study of business English. Although there is a vast literature on the subject, it is difficult to find a precise definition of collocation. However, all definitions focus on the co-occurrence of words: • You shall know a word by the company it keeps. (Firth 1957:179) • We may use the term node to refer to an item whose collocations we are studying, and we may define a span as the number of lexical items on each side of a node that we consider relevant to that node. Items in the environment set by the span we will call collocates. (Sinclair 1966:415) • ... the study of lexical patterns ... • ... a sequence of words that occurs more than once in identical form .... and which is grammatically well structured. (Kjellmer 1987:133) • ... the meaning of a word has a great deal to do with the words with which it commonly associates. (Nattinger (1988:68) (Brown 1974:1) • ... a recurrent co-occurrence of words. • ... the way individual words co-occur with others. (Lewis 1993:93) • Collocates are the words which occur in the neighbourhood of your search word. (Scott 1999 WordSmith Help File) • (Clear 1993:277) ... the way in which words occur together in predictable ways. (Lewis & Hill 1998:1) Collocation is central to the lexical approach. Hill (1999) suggests a possible extension to Hymes’ communicative competence by saying that ‘We are familiar with the concept of communicative competence, but perhaps we should add the concept of collocational competence to our thinking’ (1999:5). Collocational competence is, therefore, considered a key factor in the lexical approach for the learning of language. Studies by Bahns (1993) and Bahns & Eldaw (1993) point to the problems students have when they are unable to successfully collocate. Their views are echoed by Hill (2000) who observes that non-native speakers have problems ‘not because of faulty grammar but a lack of collocations’ (Hill 2000:49). In addition, Powell (1998), Williams (1998) and Morgan Lewis (2000), all stress the relationship of knowledge of collocation and grammaticalisation. The fewer ready-made chunks of language a speaker knows, the more they have to grammaticalise what they are trying to communicate. The more students have to grammaticalise, the more likelihood there is of making language mistakes. Morgan Lewis (2000:16) gives the example of the phrase major turning point. If a student doesn’t know this phrase, they will have to paraphrase, e.g. a very important moment when things changed completely, with the increased risk of making mistakes. There is also the danger of lexical inappropriacy. Other such examples would be: vested interest - “a strong personal interest in something because you could benefit from it“, or business acumen - “skill in making correct decisions and judgments in business “. Corpus linguistics Corpus: “the body of written or spoken material upon which a linguistic analysis is based“ (the OED) a collection of texts assumed to be representative of a given language, dialect or other subset of a language, to be used for linguistic analysis.“ (Francis 1982:7) ‘a large collection of written or spoken texts that is used for language research’ (the Collins COBUILD [1995] dictionary) Concordance: an alphabetical index of all the words in a text or corpus of texts, showing every contextual occurrence of a word: a concordance of Shakespeare's works. (http://dictionary.reference.com) a list of the words used in a text or group of texts. The normal way of consulting a corpus is to look at concordances which show words in the context in which they occur. (http://www.macmillandictionary.com/resourcedicti onaryterms.htm) Concordancer: • a kind of search engine designed for language study. If you enter a word, it looks through a large body of texts, called a corpus. This lets you look at a word in context, see how common it is, see the style associated with it. Such a tool is computer-specific. (http://www.usingenglish.com/glossary/concordancer.html) Using corpora in linguistic analysis has been a rather debatable issue lately. Among the most relevant advantages of computerized corpora, we might cite a just few: statistical objectivity (Sinclair, 1991, Stubbs, 1996), verifiability of results (Svartvik, 1992), broadness of language able to be represented (Svartvik, 1992), ready access (Svartvik, 1992), broad scope of analysis (Biber, 1995), accountability (Biber, 1995), reliability (Biber, 1995), pedagogic relevance (Johns, 1998; Kennedy, 1992) and a view of all language and new perspectives ( Sinclair, 1991; Louw, 1993). Nevertheless, there are also criticisms attached to it: focus on performance-related issues, leaving aside aspects of language that are more concerned with competence (Howarth, 1998), exclusion of intuition and common sense (Owen, 1993), problems related to size, representativeness and balance of corpora (Renouf, 1987; Sinclair, 1991), Tribble, 1997), debate over the pedagogical usefulness of frequency lists generated by corpora and the value of authentic materials for use in the classroom (Widdowson, 1990; Howarth, 1998). A personal experience Our experience with creating corpora is quite limited, due to technical constrains, as we could not create our own business English corpus. We had therefore resorted to the online resources, and we used the free online dictionaries and concordancers in order to create a set of core business lexis, organized around the lexical approach principle. We grouped words according to the grammatical category they most frequently collocate with. Thus, a word like ability is presented as follows: ABILITY n the skill or talent to do or perform sth successfully V: appraise, assess, demonstrate, develop, encourage, evaluate, foster, have, measure, over/underrate, recognise, use ~ A: artistic, average, competitive, creative, data storage, decision-making, earning, entrepreneurial, exceptional, executive, fund-raising, great, inferior, innate, innovative, language, latent, leadership, learning, legal, managerial, mental, moderate, natural, outstanding, physical, remarkable, striking, superior, uncanny, unique, working ~ P: ~ test, to assert oneself, to communicate well, to invest, to lead, to meet financial obligations, to pay, to repay, to work under pressure, to work in a team; test of ~ies We will try in the following to give a brief account of the resources and strategies we used in order to create the “Business Collocations: English-Romanian Dictionary. Let us turn our attention to the word business. This will be found in the MSN Encarta dictionary, in the following combinations: the retail business, ailing ~, poor ~, take over a ~, do ~ with sb, etc. Similarly, we might find in Cambridge dictionaries online the following structures: big, monkey, show ~; ~ class, end, park, plan; be in ~, get down to ~, etc. A bilingual dictionary (dict.leo.org) might prove just as useful: be away on ~, be out on ~, open, abandon, attend to a ~. Concordancers will also provide us with plenty of frequent collocations. Thus, the concordances generated by the Corpus Brown software, will add further collocations to our list: private, public, motel ~, come on ~, etc. Another rich resource is the Web Concordancer, which might provide us with other useful examples: local ~; experience in ~; ~ firm, manager, etc. Once the dictionary has been created, the next step was to find ways in which to teach these collocations to our business students. One of the strategies we used was to find authentic business materials, taken especially from the online business press, which we turned into vocabulary practice exercises. In the following, we will present a business article that we exploited from a lexical point of view. We extracted from the text some common collocations and starting from these, we created a matching exercise: Match the following verbs and nouns to form suitable collocations: 1. make 2. reach 3. return 4. ask for 5. state 6. do 7. burn 8. end 9. express 10. take 11. handle 12. make a) b) c) d) e) f) g) h) i) j) k) l) bridges a/the call an interest a deal a/the call business a message a number a/the call an appointment a/the call the purpose The next step is for the students to re-create the text, out of which the above collocations were extracted: Now fill in the gaps in the following text with the collocations you found above. You may want to change the form of the verbs (-ing, -ed, etc.) or of the nouns (pl., etc.): Business Telephone Etiquette for Success Proper Telephone Etiquette is more important than ever in today’s business environment. Much of our business communications takes place on the phone: in the office, at home, in the car, virtually anywhere. In this area, proper phone technique can 1. ________or break _______ or relationships. The following are some guidelines to help you use the phone as a power tool. First is the greeting. When answering the phone for business, be sure to identify yourself (and your company, if applicable). If answering someone else’s line, be sure to include their name in your greeting, so that the other party does not think they have 2. ________ a wrong ________. For example, if answering Jim Smith’s line, Bob Johnson would answer the phone “Jim Smith’s line, Bob Johnson speaking” and then 3. _________ ________ or 4. ________ _________, depending on how your office works. When you are the person 5. _______ _______, be sure to use proper phone etiquette from the start. You want to be sure to be polite to the “gatekeepers” i.e. Secretaries, receptionists etc. that answer the phone for your business contact, as they are the ones who have the power put you through, (or not) at 4:55 pm on Friday, when their boss is getting ready to leave the office. They may sit outside of the office, but they too have influence and power so a greeting such as “Good morning, this is Penny Jones, I’m 6. _______ _______from John Jones, is he available? is a bit of etiquette well spent in the long run. It would also be wise to learn the names of the top assistants, and use their names to make them feel noticed and important. Some business relationships, especially in fields like sales and marketing, start or stall right at the front desk. When you have reached the party, if your call has been expected, remind them of the prior conversation and appointment. People get busy and can seem surprised until you remind them of where they should remember you from. If your call is not expected, unless it will be a short call, ask the party if they have the time for you. Calling unannounced is much like “dropping in” and you shouldn’t overstay unless invited. If the other person does not have time, briefly 7. __________ __________ of your call and 8. __________ ___________ to follow up at a later time. Have a phone diary. Keep a pencil and pad near the phone and jot notes during phone conversations. This will help you “actively listen” and have a reference for later. Employ active listening noises such as “yes” or “I see” or “great”. This lets the other person know that you care about what they have to say. Recap at the end of the call, using your notes and repeat any resolutions or commitments on either side to be sure you are both “on the same page”. 9. __________ _________ on a positive note by thanking the other person for their time and 10. _________ _________ in speaking with them again (if that is true). If not, just let them know you appreciated them speaking with you and end the call. A gracious good bye leaves the door open for further communication and in this day of mergers and acquisitions you never know with whom you will 11. _________ ________ with in the future, so 12. ________ any ___________, or telephone lines, would be unwise. Remember, in this global marketplace, some of the most powerful business relationships have been between people who have never seen each other. (http://ny.essortment.com/businesstelepho_rtli.htm) Other types of exercises may be created, as well. Another example would be the selection of collocations that might occur in the context of a certain business situation, such as finding a job. Thus, we selected a few recurrent expressions found in job advertisements and letters of applications and we generated the following matching exercise: Find below some useful collocations that may be found in job advertisements and letters of application: a) b) shortlist apply for abilities applicant add to attend demonstrate demonstrate verbs pursue live on verbs acumen job provide negotiate earn undertake career knowledge acquire organisational tenured fringe candidates benefits high-calibre high advanced private adjectives attractive competitive commitment redundancy attractive hands-on working business adjectives promising successful experience performance total managerial in-depth degree money skills appraisal expectations advancement description incentive phrases salary holder package phrases scheme entitlement interview pension The examples may continue, and we consider that teachers themselves may put their imagination and creativity to use and come up with useful lexical practice for their students. It is nevertheless, of extreme importance, to find those collocations that are indeed most frequent in the business lexis and the knowledge of which may contribute to students’ better functioning in a business-related context. Bibliography: Biber, D. (1995). Dimensions of Register Variation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Brown, D. (1974). Advanced Vocabulary Teaching: The Problem of Collocation. In RELC Journal Vol.5, No.2, 1-11. Dudley-Evans, T. & St John, M.J. (1998). Developments in English for Specific Purposes: A Multi-Disciplinary Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Firth, J. R. (1957). A Synopsis of Linguistic Theory, 1930-55. In Palmer, F.R. (ed), (1968) Selected Papers of J.R. Firth 1952-59. London/Harlow: Longmans. Kjellmer, G. (1987). Aspects of English Collocations. In Meijs, W. (ed) Corpus Linguistics and Beyond. Amsterdam: Rodopi. Lewis, M. (1993). The Lexical Approach. Hove: Language Teaching Publications. Lewis, M. (1997). Implementing the Lexical Approach. Hove: Language Teaching Publications. Lewis, M. & Hill, J. (1998). What is Collocation? Hove: Language Teaching Publications. Lewis, Morgan. (2000). There’s Nothing as Practical as a Good Theory. In Lewis, M. (ed) Teaching Collocations. Hove: Language Teaching Publications. Nattinger, J. (1988). Some Current Trends in Vocabulary. In Carter, R. & McCarthy, M. (1988). Vocabulary and Language Teaching. London/New York: Longman. Sinclair, J. (1991). Corpus, Concordance, Collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Sinclair. Philadelphia/Amsterdam: John Benjamins.