Institutionalized incapacities and practice in flood disaster

advertisement

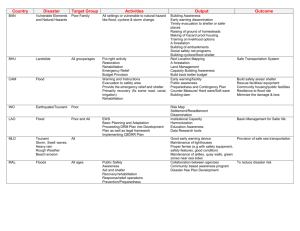

Institutionalized incapacities and practice in flood disaster management in Thailand By Jesse Manuta, Supaporn Khrutmuang, Darika Huaisai & Louis Lebel. Unit for Social and Environmental Research, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand (jesse@sea-user.org) ___________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT This paper focuses on the institutional capacity within the Thai nation-state to manage floods and the risks of flood-related disasters. The research aims to understand how various laws, policies, programs and procedures for managing floods and the risks of flood-related disaster came about and how they have performed. It further examines the capacity to mobilize and coordinate resources as well as deliberate, negotiate, monitor and evaluate the formal institutions from the national to local level. Focusing the analysis on institutional changes and river-based flood events during the last two decades, the paper explores ways of reducing the risks of flood disasters in ways that do not further disadvantage already socially vulnerable groups. Documents and reports were reviewed. In addition, interviews and field observations on site after flood events were carried out. There are indications of improved institutional performance of the government in the areas of relief and emergency, the formation of the flood disaster emergency committee at the outset of the monsoon season in flood prone areas, and initial efforts to involve communities in flood prevention and mitigation. Several institutionalized incapacities, however, continue to undermine the provision of assistance and services that would reduce the risk of flood disaster. Poor coordination across administrative bodies and line agencies results in fragmented flood mitigation and prevention intervention measures. Flood disaster victims are left alone to fend themselves especially in remote areas due to incomplete implementation, poor follow up, and structural biases. Many problems are aggravated by the absence of monitoring and evaluation of state agency’s performance. Social mobilization on flood management may be necessary to re-enable these institutions to perform the roles in society for which they were intended – reducing vulnerabilities and risks of flood disasters. 1 Introduction The capacity of households, communities and nation-states to live or cope with floods and to adapt to changes in flood regimes wrought by their own and others’ development activities depends on many factors. Economic factors, like the dependence or vulnerability of livelihoods on seasonal flooding, and the level of financial resources of a household or state to undertake structural measures or cope with and recover from losses are undoubtedly important. Ecological factors, like the extent of riparian vegetation and natural or human-modified flood plain habitat or level of sediments and other debris in floodwaters affect immediate impacts and longer-term ecological services, such as soil productivity and water quality. Social and cultural factors, likewise, are critical. Institutions such as formal insurance mechanisms, community and kinbased safety nets are important in recovery. Policies, programmes and procedures that assign responsibilities and roles, coordinate collective action and decide and allocate budgets for infrastructure investments in prevention, mitigation and emergency relief may make the difference between a flood and a flood disaster. Dysfunctional or perverse institutional arrangements may increase vulnerabilities to floods and risks of floodrelated disasters. Seasonal flooding is a regular feature of the Monsoon climate and flood plain landscapes of Thailand. Most of the major cities in Thailand, including historical and current capitals of Kingdoms, like Chiang Mai, Ayutthaya and Bangkok, have been built on the foundations of rice-growing civilizations in major flood plains. Communities where livelihoods depend on a seasonal cycles of flood have learnt to live with floods and embrace its arrival with songs and dances. Institutions and cultural practices around the management of floods are persistent and have survived for centuries. Why should floods suddenly become a problem? The answer is that, over the last few decades, industrialization and the accompanying processes of urbanization have led to very different land-use patterns, economic structure and livelihood base. Agricultural practices have also changed with multiple rice crops in highly regulated irrigation systems now common in the rice-bowl surrounding Bangkok. Today, even relatively modest river flows could result in damaging floods, so structural measures to control floodwaters have proliferated. Unfortunately, these have often created new problems – by shifting the flood risks somewhere else or by creating incentives for further floodplain development in high risk areas protected by modest dykes and diversions (Lebel et al. 2005a). The institutional response, made possible by shifts in philosophy, technical capacity and working style within the Thai bureaucracy, has been significant with new approaches to flood and disaster management. For example, in October 2002 the Royal Thai Government reoriented policy rhetoric from an emphasis on relief and rehabilitation to a more pro-active integration of mitigation and preparedness in the overall disaster risk management (Tingsanchali et al. 2003). This was heralded by several new assignments and roles for different state agencies and the creation of new Department focussed on Disaster Prevention and Mitigation under the Ministry of Interior. The reorientation of disaster management framework and the restructuring of institutions governing the management of disaster in the country emanates from the Eighth National Economic and Social Development Plan (NESDP 1997-2001) that calls for development strategies for human development, poverty reduction and reducing vulnerabilities to disaster. But what are the implications of these and related changes for institutional capacities on the ground? This paper focuses on the institutional capacities within the Thai nation-state to manage floods and the risks of flood-related disasters. Our objective is to understand how various laws, policies, programs and procedures for managing floods and the risks of floodrelated disasters came about and how they have performed from the national to local level. We focus our analysis on institutional changes and river-based flood events during the last two decades. Thus we don’t directly address the Asian Tsunami disaster in coastal Thailand in December 2004 (e.g. Manuta et al. 2005), but its repercussions for disaster management more generally are considered. Ultimately we are seeking ways of reducing the risks of flood disasters in ways that do not further disadvantage already socially vulnerable groups. The rest of this paper is divided into four parts. After a brief description of our main methods and introduction to the case study areas we present our findings on institutional capacities. This analysis reveals several major problems that result not from an absence of institutions, but rather the prevalence of poor design—lack of clearlydefined roles and responsibilities, absence of check and balances and monitoring and evaluation—that prevent appropriate responses, what we are calling “institutionalized incapacities”. The final section reviews what have been learnt from our analyses in Thailand and considers their implications for thinking about flood risk reduction program elsewhere in Asia. 2 Methods and Study Area Our approach was twofold. Firstly, the formal institutions created by the state to deal with flood related disaster and how they have changed overtime were reviewed through reviewing documents and interviews. This followed the general framework for assessing institutional capacities (Lebel et al. 2005b), focusing on four classes of institutionalized capacities, namely: The capacity to mobilize and coordinate resources. The capacity to implement The capacity for deliberation and negotiation; and The capacity for monitoring and evaluation. Important Thai language documents reviewed included municipal flood prevention and mitigation plans, national handbooks and Master Plans by current and earlier central agencies. Likewise, earlier findings of research on disaster management in Thailand were examined. Secondly, research was carried out about practice and performance in recent flood events that caused loss of life, property and livelihood. This included more in-depth research in three locations where floods had occurred. Essential features of the three case study areas are given in Table 1. In practice, there were significant differences even within the case study areas and, therefore, two or three locations within each wider case study were studied. Field observations, group discussions, interviews, and reviews of secondary materials were carried out at each site. In addition household-based surveys were made in the two Chiang Mai case studies. These covered: experiences and impacts of floods, mitigation and prevention measures, relief, compensation and rehabilitation strategies and actions, and social mobilization. The field-based work helped us to understand how different agencies work together, differences in interest and understanding among stakeholders, and some gave insight into the actual rules of engagement among agencies and the public. The detailed analysis was complemented with a more general review of primarily newspaper accounts of larger flood-related disasters occurring in the past 20 years (1985-2005). Among these, three other events in particular were important sources of understanding of our analyses: the November 2000 flood in Hat Yai, Songkla province (Tanavud et al. 2004; Assanangkornchai et al. 2004; Viriyakoson et al. 2001), the Petchabun flood and landslide disaster in 2001 (Parnwell et al 2003; ENS 2001), and the Nakorn Srithammarat flood and landslide disaster in 1988 (Lakanavichian 2001). Table 1. Features of the Normal Flood Regime and Disaster Events in the Three Case Studies. District Om Koi,Chiang Mai (Province) Saraphi & Muang, Sena & Muang, Chiang Mai Ayutthaya Location of upland and lowland villages urban settlements in the urban and rural settlements study sites located in the upper flood plains of the Ping in the flood plains of Chao tributary valley of the Ping River in Chiang Mai Phraya River River Flood regime Flash-flooding and Abnormally high seasonal Abnormally high seasonal and disaster landslips (rainy season river flood from bank spill- river flood from bank spill- risk only) from intense rainfall over in Muang & Saraphi. over. Flash-flooding from run-off Water release from and creeks from Doi Suthep upstream dams invents in upper tributary watersheds mountain near city. Most recent The 20 May 2004 flash Water overflowing from Water overflowing from disaster-causing floods swept away houses Ping River due to heavy Chao Phraya in 2004 due to flood events and fields in Ban Luang, rainfall (20 May 2004; 14- water being released from Tambon Mae Tun and 16 August 2005) the dam following heavy landslides had similar inundating urban downpours in the North. impact in an upland Karen settlements in Seraphi and village of Ban Mapota, one Muang. of the cluster of villages that form Moo 9, Tambon Sobkhong Flood control projects to protect irrigated agricultural land shifted floods to residential and market areas in Sena. 3 The Players The present flood disaster management system in Thailand evolved from the Civil Defense Act of 1979 and the Bureaucratic Reform Act in October 2002. The Civil Defense Act of 1979 prescribes the jurisdiction and responsibility of concerned organizations and a systematic process of disaster management (ADRC 1999). The Bureaucratic Reforms in 2002 restructured the institutional arrangements for disaster management in the kingdom (DDPM 2005). The key agencies can be classified into two groups: (1) national flood disaster-related agencies, and (2) administrative bodies from national to local level. 3.1 National flood disaster-related agencies The Civil Defense Act 1979 has been the legal framework of disaster management in the country. It defines what constitutes a disaster, the scope and key agencies responsible for disaster management. Floods, together with fires, storms and other natural and manmade disasters constitute what the Act defines as “public disaster.” Since the 1980s, the government agencies, which are responsible for disaster management, are classified as strategic body and functional agencies. On one hand, the strategic body, the National Civil Defense Committee, has the duty to formulate civil defense measures and policies. The functional agencies, on the other hand, have the administrative duty to respond and manage disaster from the national to local level (ADRC 1999). In October 2002 the government reformed and restructured disaster management in Thailand. The restructuring led to the creation of the Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation and assigning lead responsibilities to specific department for, more or less, different phases of the disaster cycle, with the aim of ensuring coordination of disaster management nationwide in September 2003 (Table 2). Table 2. Roles and Responsibilities for Disaster Management After the October 2002 Reforms. Department Disaster Prevention and Ministry Interior Mitigation Water Resources Responsibility Coordinate flood prevention and mitigation plans from different agencies Environment and Policy advice on national water policy; Natural Resources plans, coordinate, monitor flood mitigation and national water resource management All departments Meteorological Social Development and Carry out rehabilitation and social and Human Security economic recovery Information and forecast and early warning systems Communication Technology Irrigation Public Works and Town Agriculture and Water provision, storage, maintenance and Cooperatives allocation Interior Infrastructure rehabilitation and provide and Country Planning development planning guidelines Source: (DDPM 2004; DWR 2005). Consolidating various departments with disaster management programs, such as the Division of Disaster Relief under the Department of Social Welfare and Accelerated Rural Development Department, among others, the Royal Thai Government established the Department of Disaster Mitigation and Prevention in 2002 as the coordination centre for prevention, mitigation and recovery measures (Teeraoranit 2003). The key role of the Department is coordination, namely; to gather flood prevention and mitigation plans from different agencies. The Department is mandated to draft Master Plans, set up measures, promote and support disaster prevention, mitigation and rehabilitation through the establishment of safety policy, prevention and warning system, rehabilitation of disaster devastated area, follow-up and evaluation (DDPM 2005). However, it seems that the stated mission of the Department is beyond the capacity and capability of a newly established Department. As part of the bureaucratic restructuring at the end of 2002, the Department of Water Resources was established as the main agency for formulating management plans, as well as monitoring, coordination and implementation of water resources conservation and rehabilitation (DWR 2005). It is also the lead agency for flood control and mitigation in the 25 river basins in the country. Mitigation seems part of integrated water management with involvement of all stakeholders (DWR 2005: 20). It has completed the Integrated Plans for Ping and Pasak Basins in 2003 (DWR 2003), and expects to complete the rest in 2005 (DWR 2005). Support for the formation of multistakeholder bodies known as “river basin organization” is a key part of its strategy. The Royal Irrigation Department is one of the more historically powerful agencies of development in Thailand with responsibilities for water provision, storage, maintenance and allocation. Its extensive system of irrigation canals, gates and pumps are also used as flood protection and drainage facilities in the wet season. The Department has also participated in the design, construction and operation of some of the major dykes and pumping projects for the protection of suburban areas of Bangkok (ESCAP 1999). Merging the Departments of Public Works and Town and Country Planning, the new Department focuses on one hand the infrastructure rehabilitation after the disaster, and on the other hand, provides development guidelines for urban settlement environment development. The Department proposes policy and development plans in land uses and public works. It adopts zoning to delineate residential areas and categorize settlement density, and proposes layout of the road network and drainage and flood protection infrastructure. Infrastructure rehabilitation is also the responsibility of the Department of Disaster Mitigation and Prevention. Several important agencies have been involved with flood-related disaster management. As a result of various public pressures following devastating flash floods in Nakhorn-SriThamarat, Southern Thailand in 1988, the Royal Forestry Department imposed a total log ban in natural forests in 1989 (Lakanavichian 2001). The Land Development Department provides zoning of different land-use types within the watershed (ESCAP 1999). The development of the National Civil Defense Policy Plan in 2002 by the Department of Local Administration provides a master framework and guidelines on developing action plans on disaster management at the provincial and district level. The Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand has the key responsibility in the operation of the multi-purpose reservoirs for electric power generation facilities. The Harbour Department is responsible for navigation in the main river and its navigable tributaries, and undertakes channel improvements, which may have flood control impacts. The Port Authority of Thailand operates and maintains the port of Bangkok. It maintains and improves the channels of the lower estuary and has a direct interest in flood control works, which would affect the navigability of the rivers (ESCAP 1999). 3.2 Administrative structural bodies The Thai state has been administered through a highly centralized bureaucracy, which over the past century, has expanded its’ reach into all but remotest upland corners of the territory. Typically new institutions of the state bureaucracy first overlay rather than replace existing locally diverse structures, for example, with respect to management of water, land and floods. The interplay between institutions can be reinforcing, complimentary or conflictual and may or may not lead to the replacement or modification of local institutions (Lebel 2005). Opportunities for such interactions have increased with decentralization reforms. For this reason, any investigation of institutional capacities must go beyond cataloguing the formal institutions and organizations of the state, but this is a reasonable place to begin. With the government reform in 2002, the administration structure of the flood management in the country is designated into 3 levels: national, provincial and local. At the national level the Prime Minister is the head master of command through the Minister of Interior who presides, as the general-director of the Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation. Chaired by the Minister of Interior, the National Civil Defense Committee is responsible for formulating policy on disaster management and prevention. It likewise, supervises all activities relevant to civil defense and disaster management. The Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation is the secretariat of the committee (DDPM 2005). At the provincial level, the Provincial Civil Defense Committee is headed by the Governor of the province and the membership of the committee comprises representatives from various government disaster-related agencies. Under the Civil Defense Act of 1979, the governors are empowered to call different agencies to provide relief in case of major disasters. Flood Mitigation and Prevention Ad Hoc Committees are established in each flood disaster-prone province to prepare and plan for the eventual flood disaster. However, some of these committees were only established after the disastrous floods occurred. For example, the Hat Yai Flood Prevention and Mitigation Management Committee, was created after the catastrophic floods in 2000. At the district level, the District Chief Officer heads the District Civil Defense Committee. Headed by the Mayor, the Municipal Civil Defense Committee comprises the Directors of Bureaus and Division of the municipal office. Each municipality is responsible for civil defense and disaster management. The Tambon Administrative Organization prepares annual budget for disaster relief and emergency and collaborate with the District Disaster Relief Committee for damages investigation and distribution of compensation in the village. 4 The Rules As discussed in the preceding section, the Civil Defense Act of 1979 and the Bureaucratic Reform Act in October 2002 describes the roles and responsibilities of key agencies and administrative bodies in flood disaster management in the country. However, there are no encompassing policies and laws that cover flood mitigation, control, and flooddisaster rehabilitation and recovery. What we have are related policies, laws and ordinances that are either directly or indirectly affecting different phase of flood disaster and management in the country. These policies and laws can be grouped into three categories: (1) flood control and mitigation, (2) land and water use control, and (3) relief and compensation. 4.1 Flood control and mitigation Flood control and management has become an important component of water resource infrastructure development. The post-World War II up to the 1980s marked the massive water infrastructure development in the kingdom aimed at flow regime regulation and water conservation (ESCAP 1999). Water resources projects have been a major public investments since 1961 (ESCAP 1999). Several large and small-scale water resources projects were constructed for power generation, irrigation and flood mitigation nationwide. The Royal Irrigation Department has been mandated to protect agricultural areas with dikes. For example, a 300 km dyke has been constructed by the Royal Irrigation Department along the Chao Phraya River to protect irrigated areas from Nakhom Sawan to Bangkok (ESCAP 1999). Flood mitigation is one rationale for medium to large scale water infrastructure projects in the Mae Nam Ping Basin in Northern Thailand. In Thailand economic activities and prosperity is concentrated in the Chao Phraya River basin, particularly the Greater Bangkok Metropolitan Area, and few other urban and industrial enclaves. The government invested in flood control infrastructures to control flooding in these urban centers. Since the beginning of the Eighth National Economic and Social Development Plan (1997-2001), the government has allocated necessary budget to various agencies concerned to implement various flood control measures, such as the construction of flood control systems, multi-purpose reservoirs and other hydraulic works, aiming at reducing the magnitude of flooding. For example, as a response of the catastrophic flood in Hat Yai in 2000, the Hat Yai municipality with the support of the national government has made considerable investment in flood mitigation schemes, which include the construction of levees, drainage canals, water diversion channels and pumping stations (Tanavud et al 2004). The Eighth National Economic and Social Development Plan calls for the establishment of institutions to solve flood problems through the formulations of policies and action plan. These institutions would coordinate the implementation of the action plan so as to ensure effective flood management in conformity with the law and complementary of the activities of all departments concerned working toward the same goals and preventing conflicts. 4.2 Land and water use control The Department of Land Development and the Department of Public Works and Town and Country Planning issued development criteria for watershed and urban development, respectively. In order to prevent flash floods, any land-use activity, except conservation and rehabilitation, are not allowed on steep sloping areas beyond 35 %. Control measures and appropriate cropping patterns are recommended to minimize surface run-off and soil erosion in milder-slope areas (ESCAP 1999). The Town and Country Planning Department Community provides the following criteria for urban expansion and settlement, namely: The settlement area should not be located in wetlands, flood-prone areas and locations that obstruct water flow; The settlement area should not be in a steep-slope zone which is prone to flash floods and land slides; The settlement area should be located away or set back from the coastal area for a certain distance to reduce risk of flooding; The green area, the area of agriculture, should be in between the community areas in order to absorb water and to slow down the flow; and Settlement density, space between buildings, standards for landfill, and layout of the road network and drainage system should be clearly identified. The guidelines, however, are not followed (ESCAP 1999). Pumping of groundwater is one of the main causes of land subsidence, which resulted in deeper flooding and longer water logging in metropolitan Bangkok. In March 1983, the Cabinet issued a resolution on the mitigation of groundwater and land subsidence by a yearly step-by-step increase in stricter control of groundwater uses from 1983-2000. The measures for controlling private pumpage are implemented through the Groundwater Act (1977), enforced by the Department of Mineral Resources. The Department has adopted a policy of not granting permission to construct a new well in areas where there is adequate public water supply. Although the groundwater level in central part of Bangkok has improved with the pumping regulation and rehabilitation programme, the water level in the outskirts of Bangkok has continued to decline due to housing and industrial activity (ESCAP 1999). The Canal Maintenance Act controls waste in the waterways and roads to prevent blockage or reduce the drainage capacity of the community drainage system to natural rivers. The Local Government Act (B.E 2496, Sec 51) has mandated the municipality to maintain drainage channels within the municipal area. Likewise, the Sub-district Council and Sub-district Administrative Organizations are mandated to maintain drainage channels in their area of jurisdiction (B.E. 2537, Section 68). Municipalities are authorized to prescribe local laws through the Municipal Act, the Public Health Act, and the City Cleanliness and Disciplines Act. However, local government has not enacted yet specific laws related to community flood protection and mitigation. Other government laws that relate to floods and flood management include: the Navigation in Thailand Territorial Waters Act (B.E. 2456), the Highway Act (B.E. 2535), the Field Dykes and Ditches Act (B.E. 2505), the Land Allotment Control (B.E. 2515), the Building Control Act (B.E. 2522) and the Building Control Act (Second Issue, B.E. 2535), among others. 4.3 Relief and compensation Before the Government Reform in 2002, there were no guidelines for the mobilization and allocation of relief funds (ADPC 1998). Since flood disasters were unexpected and unforeseen, relief and emergency funds were not included in budget allocation before a disaster occurred. Mobilization of funds was based on public pressure for the government to act. Provincial governors and other local agencies prepared their own damage assessment and request for relief, repair and rehabilitation. As noted by ADPC there had been a disparity in collecting and compiling national damage assessment data. The mobilization of funds was then based on the ministers and other political leaders’ request to the Bureau of Budget, which most often depended on political patronage (ADPC 1998). The Treasury Act of 2003 defines the mechanisms for allocating disaster relief assistance. Funds for disaster relief are budgeted by the Prime Minister’s office and several ministries. The formal process for obtaining relief assistance is administratively nested in local government units at the Tambon Administration Organization level first appeal to the District Level and so on upwards if funding levels are not enough. The Tambon Administration Organization has an annual budget for disaster relief and emergency, and if the budget is insufficient, the Tambon head can request to the district level. The governor has allocated .5 million baht at the district level, and at the provincial level, the allocated budget for disaster relief assistance is 50 million baht. The Departments of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation, Fisheries, Livestock, Agricultural Extension and the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security are responsible for payment of compensation for death, damages and loss of property and livelihoods. A committee is formed at the district level to investigate the losses and damages. The committee comprises the district office, Agricultural Office, Livestock Office, the Department of Disaster Prevention & Mitigation, the Tambon Administrative Organization, the village head and the deputy head (DDPM 2003). At the village level, the village head, the deputy and Tambon Administrative Organization play a critical role in investigating and reporting the damages to the district emergency committee, who will then inform and liaise with agencies that provide compensations to the villagers. In the last two decades as a result of economic growth, democratization and the adoption of modern information technologies the Thai bureaucracy has grown tremendously in capacity and in size. The new bureaucracy is young, computer literate, systematic and transparent relative to its predecessors. But, how have these changes contributed to management of risks of flood-related disaster? 5 Institutionalized Incapacities and Practices 5.1 Poor coordination Coordination is critical in flood disaster management to overcome the invariable fragmentation that results from departmental specializations, and geographic boundaries, and among operational phases in the disaster cycle. Coordination begins with sharing of information, but also requires the capacity to influence how such information is used and various intervention measures implemented. We have identified three different classes of coordinating problems. The first case concerns relief and compensation distribution at the village level. The village head and the Tambon Administrative Organization provide early assessment of the impacts of the floods to the District Chief right after a disastrous flood occurs. The District Chief will immediately form a committee on disaster relief assistance. Under that committee an investigation subcommittee is created to investigate and monitor damages of floods. The relief assistance and compensation in Ban Luang, in Omkoi District, Chiang Mai after the May 2004 floods and the post-26 December 2004 tsunami in Southern Thailand indicated problems of unfair distribution of support among households and areas. There was no investigation committee created to assess and monitor damages and administer compensation at the village level. The responsibility to provide information on death, property losses and damages to the district was solely left to the village head. Without the Investigation Committee, the process of reporting and compensating damages at village becomes a contentious issue as some households, usually relatives of the village head, got more than others. There was also problem of transparency and accountability of local leaders. Disparity in the distribution of the relief and compensation lead to division within communities. The failure to properly account and validate losses and damages at the village level contributes to the weakening of communal solidarity, which is badly needed as the village undertakes livelihood recovery after the flood disaster. The second concerns the interactions of national agencies and the local administrative organizations. Coordination between national agencies and the provincial or district government unit was hampered when certain issues which required decision of the national director of the line agencies in Bangkok. For example, in Sena, Ayutthaya Province the District Chief intervenes on behalf of the affected flooded communities to request the Regional Director of the Royal Irrigation Department to open the irrigation water gate to drain water out of the flooded area to the rice fields. The Royal Irrigation Department’s flood control measures to protect agricultural lands from floods resulted in the diversion of floods to the market and residential areas of the district. However, the ultimate decision has to come from the Royal Irrigation Department Director-General in Bangkok. The authority and knowledge of the district and the regional office of the Royal Irrigation Department in Ayutthaya proved to be meaningless as the key decision was made in Bangkok. The process of budget preparation and allocation procedures hampers coordination between local government and line agencies. In Chiang Mai, the Department of Water Transport was not able to participate and extend the Municipality’s river training project beyond the municipality’s boundary since it was not part of the approved project of the Department. Budget allocation for infrastructure project has to be approved at the national level, and the Department had no contingency budget to supplement the Municipality’s project. Poor communication is an underlying problem. The recent Chiang Mai floods on 14-16 August 2005, considered as the worst flood disaster in 40 years, illustrates problems. The timing and the manner in which the warning is disseminated is crucial. In Chiang Mai the Royal Irrigation Department set up a special task force among the different managed water projects by the Department in the Upper Ping River Basin to monitor the river water levels. The Department then informs the Municipality. The Municipality also coordinates with the Meteorological Department on water level during heavy and continuous rainfall. However, the recent flooding indicated that the warning was given few hours before the floods reached Chiang Mai. The warning was broadcasted in Thai mostly in identified flood risk areas of the municipality. There was not enough time for the people to prepare. The third problem is the coordination of key agencies in flood disaster prevention and mitigation. Flood disaster-related agencies continue to plan and implement projects in their area of responsibility or jurisdiction without regard to the impact of their activities on others. There is no integration of flood disaster prevention and mitigation plans for projects of the Royal Irrigation Department, the Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation, the Departments of Public Works, and the Department of Harbor, among others. The government’s initiative to form the Department of Water Resources aims to provide organizational framework for the integrations of perspective, framework, approaches and strategies for flood disaster management. However, there are a number of structural impediments for such integration. As a newly established Department, coordinating with other agencies with a long-standing mandate for organization and budgeting of water disaster-related programs and project proves to be challenging without the passage of an enabling law that defines the framework, mandate and organization of water disaster-related management in the country. Moreover, development agencies responsible for urban planning, housing and social welfare and public utilities have not been well linked to disaster risk reduction programs. For example, in Chiang Mai city the construction of elevated roads and landfills for housing estates has disrupted local irrigation and semi-natural drainage systems. It has also shifted flooding risks to the poor in low-lying areas. In Ayutthaya and Sena District hundred acres of rice fields were transformed into industrial estates despite existing land use zoning of the Departments of Public Works and Town and Country Planning. Coordination across scales is as problematic because of hierarchical arrangements within each line department and ministry. Much of the decision-making must cascade back up to the Minister or Deputy Minister level. Unfortunately organizational interests and inter-bureaucratic competition appear to create barriers among officials that would otherwise cooperate. Cross-scale coordination among agencies and stakeholders is important for flood mitigation, particularly in the design, implementation and monitoring and evaluation of program and policies that help address the underlying causes of flood disaster risks. Poor coordination has been institutionalized as a result of bureaucratic competition that starts at higher levels in the Ministry. Unfortunately, the persistence of organizational interests has not resulted in creative competition, but rather a diminished overall capacity to reduce the risks of flood disasters. 5.2 Incomplete implementation Incomplete implementation in terms of geographical coverage, unfulfilled promises, and unattained goals is common, and this was usually attributed to lack of financial or human resources. Our studies in Thailand suggest an alternative, less attractive, explanation: discrimination and poor priority settings that result in those least able to influence the distribution of involuntary risks bearing the largest burdens. Our case studies in Ban Mopota and Ban Luang in Omkoi district, Chiang Mai Province, in particular, revealed disturbing aspects of current institutional arrangements. Fortunately, this was a relatively “moderate” flood event. The floods accompanied by severe landslides in and around several villages in Omkoi district in May 2004 caught the people by surprise. There were no early warning systems in place. In Ban Mopota it took 3-4 days before emergency relief arrived. Nearby villages organized food and shelter for affected people in the early days after the disaster. However, a month later, the people in Ban Mopata, were facing starvation as their crops, livestock and homes were devastated and thus their primary livelihoods had been destroyed. Relief assistance (food relief and supplies) that came late from the private and local government lasted only a few days. There was no follow-up assistance provided by the state. The argument was made that many of the villagers did not have Thai identification cards and therefore could not be compensated, for example, for loss of livestock and agricultural damages. Some compensation, however, was given for loss of shelter on humanitarian grounds two to three months after the floods and landslides. All of the villagers received such compensation ranging from 18,000 to 20,000 Baht. The delay of compensation was partly due to the procedures, which the Karen villagers were not aware of on one hand, and the slow process of dispensing compensation on the other hand. The villagers were not informed that they have to inform the TAO or the district officer about the lost and damages within 3 days after the floods. Informing the local authorities means a one day walk to inform the TAO and the district, 2 days. If the hill were not enough of a barrier, language would have been. The requirement to have a citizenship card for access to several basic services is a major social justice issue in the north, especially given that in a substantial number of cases it is the state authorities themselves which have been slow in recognizing ethnically diverse populations as Thai and after having done so been slow again in correcting past discriminatory practices. In any case arguments could be made that in the case of flood disasters citizenship should be a secondary consideration. The situation in Ban Luang, a predominantly rural Thai farming village, was a bit better. Relief supplies reached the village soon after the flood event due to good communication facilities and proximity to paved roads. Food and relief supplies were provided from the local government, the privates sector and the neighbouring villages. The Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation provided temporary shelter. The biggest problems came later. Villagers complained about corruption and prejudice in the distribution of emergency relief supplies and administering of compensation. Some emergency relief supplies were stored at Tambon Administrative Organization office for a week before they were delivered to the villagers. The relief were first distributed to the relatives of the village headman. Conflict over compensation allocations surfaced due to irregularities in accounting, lack of transparency and poor accountability of the village head. The villagers called for an investigation by the District Chief. At the same time, they set up 25 respected village members as a Board of Inspectors for the compensation process. The village Head was expelled and the election of new Village Head was set up. Compensation was provided 2-3 months after the flood. Post-flood disaster interventions in Ban Luang included a-two day training on flood prevention and preparation among the people of Tambon Mae Tun conducted by the provincial office of the Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation. No follow up training was conducted since then. The Departments of Community Development and Livestock also conducted a one-off intervention by providing technical training on mushroom culture and pig rearing, as well as start-up capitalization of 100 USD. There was no follow-up and the project failed. The Bank of Agriculture and Cooperative offers a loan exemption for one year for clients affected by floods: If the flood-related damages exceeded more than 50 % the loan exemption will be extended one to five years and possibly terminated depending on the bank’s investigation and evaluation. But villagers a year after the event said the scheme had not been implemented. Some feared fines of 3% of loan interests for late repayments. The Tambon Administrative Organization of Mae Tun also came under criticism from villagers of Ban Luang for inaction with respect to upgrading a river embankment for Ban Luang. This delayed post-disaster recovery for a year as farmers were afraid of reinvesting in gardens and orchards without the additional protection being in place. But the Tambon head argued that the bureaucratic procedures delayed the process. Unfulfilled promises are a recurrent lament of flood victims in Thailand. The state provided relief and emergency, but after that the people were left to fend for themselves. Remote areas, in particular Ban Mopota received minimum assistance after the flood disaster. In our work there were many promises made soon after the event, but follow-up suggests that many of these will not be fulfilled. Ms Onnucha Huatasing, who won an award for Disaster journalism put it aptly: “After the tragedy, several government agencies were quick to offer help. But when I returned, everything was still the same.” In Petchabun Province during the 2001 flash flood catastrophe compensation for loss of life and dwellings was quite fast (Parnwell et al 2003). However, there were significant delays in receiving help in rehabilitating farmlands. The land rehabilitation, which was promised earlier by the Department of Agricultural Extension, commenced almost two years after the occurrence of the disaster. Vegetables seeds, fertilizers and pesticides were provided earlier, but farmers could not commence farming without rehabilitating their farmland covered in mud, sand and log debris. Tired of waiting of government’s promises, some households undertook the task of rehabilitating their land themselves, spending as much as 10,000 baht per rai for hired tractors (Parnwell et al 2003). The failure for the state to deliver appropriate and reasonable resources and assistance, either as a result of the incapacity of the institutions or the mere absence of the state agencies in remote places, prompted communities to take actions and mobilize local resources as well as liaise with local and regional agencies for the implementation of measures to reduce communities’ vulnerabilities. The case of Ban Luang in Omkoi illustrates the community’s effort to address the anomaly and corruption in the distribution of relief supplies and compensation assistance. They have established systems where accounting of damages and compensation procedures that are transparent and acceptable to the whole village. They also negotiated with the state for a new relocation area, but the state was not able to find suitable and safer place where all of the villagers can be accommodated. They set up a task force to monitor the water level during the monsoon season. They also raised funds for the construction of the community’s school. They have also proposed flood mitigation and prevention plans and sought the assistance of the regional office of the Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation in Lampang. The community has been pushing the Tambon Administrative Organization to actively coordinate with the regional authorities. Community-based disaster risk program redefines relationships between the people and state disaster management institutions. Acknowledging a role for communities in disaster management creates opportunities to broaden participation on the one hand, and improve accountability and responsiveness of state’s institutions on the other. Community participation may focus on empowerment and linking community-based activities with local development policies (Shaw 2004). Active participation in district area planning, river-basin management, disaster preparedness plans and water-related disaster policies are some of the avenues for engagement. Overall, however, not much is really known about what makes for effective partnerships and division of responsibilities between more centralized disaster management authorities, community organizations and local government. There is always the likelihood that the community or participation discourse is manipulated in ways that shift responsibilities and burdens to community organizations or local governments without corresponding increases in resources or decision-making powers. On the other hand, decentralizing all resources and functions could be very inefficient and lead to no single community having access to level of resources when needed. Poor prioritization of marginal communities has led to institutional incapacity of the state to bring prevention, mitigation, recovery and even relief operations to where they are, arguably, most needed – the places where the poor and other socially marginalized groups live. Ultimately it comes down to issues of accountability, responsibility and justice. 5.3 No monitoring and evaluation The capacity to monitor and evaluate flood prevention, mitigation, relief and recovery operations and institutional arrangements would create opportunities for learning and improve the accountability of authorities (Lebel et al. 2005b). However, institutionalized monitoring and evaluation procedures of the disaster management system in Thailand are absent. These capacities are poorly supported in work programs. In many ways the protection of bureaucratic interests and a culture of uncritical promotion of performance have institutionalized an incapacity for evaluation and critical reflection. For example, the politics of blame most often shifts the attention of the public to farming practices and forest extraction in the uplands as the main culprit of the flash floods in the lowland urban centres. The public discourses after the catastrophic flash floods and landslides in Petchabun Province in 2001 and Nakorn Sri Thammarat in 1988 focused on the uplands and resulted in a public outcry calling for logging ban, resettlement of upland people and infrastructure projects (structural interventions) that control flooding. The prevailing belief that forest can prevent or reduce floods resulted in policy measures to arrest the continuing deforestation in the uplands. But the direct links between deforestation and foods are far from certain. The analysis of FAO Technical Corporation project indicated that the causes of devastating flash floods and landslides in Nakorn Sri Thammarat in 1988 were the interaction of excessive rainfall of 1,051 mm in six days, topographic conditions, soil conditions and conversion of forests into pararubber plantations (Lakanavichian 2001: 15-17). The outcome is shifting the public attention away from the underlying structural and social causes that underpin vulnerability in the lowland urban centres. The over simplification of the forest-flood links results in unnecessary hardships for segments of society that become scapegoats for flood-related disaster and damages. The interventions across different phases of disaster merits careful examination and monitoring as well. A disaster doesn’t end the day the floodwater resides and emergency relief operations declare success. Although on a moderate scale, the May 2oo4 flash floods and landslide were the most devastating floods that the people of Ban Luang and Ban Mopota in Omkoi District had experienced so far. Disaster preparedness among government agencies at the local level (Tambon Administrative Organization and the District) was inadequate, largely because of a lack of experience of crisis of this magnitude. The reconstruction efforts in these areas proceed without the impetus of insights from experiences. This is a window of opportunity for local agencies and communities to learn to adapt with the crisis. What prevent us form getting better? One reason is institutional practices in planning. We looked at the yearly Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Plans at the provincial level for the Ad Hoc Committee on Flood Prevention and Mitigation in Ayutthaya and we found out that the planners were simply changing the date of the plan of the previous year. There was no review or evaluation at all in the planning process that could take into account problems with past interventions or possible changes to the flood regimes that these or other factors had caused. Another reason is that most of the planning is done by remote officials and consultants with little consultation of local expertise. Thus, in Sena the construction of the concrete wall that protects the market place was prepared by the City Planning and Public Works in Ayutthaya and Bangkok. Our interviews suggested that if local consultation had been undertaken much more attention would have been given to the impacts of the structural interventions on the opposite bank of the river. The fragmentation and compartmentalization of flood related disaster management despite efforts at creating coordination mechanisms nationally as a new department, and locally through task forces or committees continues to prevents learning from and across projects, scales of management, and agencies with roles in different phases of the disaster cycle. Democratizing approaches to disaster management appear important for creating learning institutions in Thailand. Allowing flood victims to participate in the design of measures and approaches in flood disaster management may provide valuable local insight in the planning processes. Insights from those whose livelihoods depend on the productive functions of “normal” seasonal flood cycles are very important in determining the threshold level after which floods becomes a risk on their livelihood and well-being. The participation of the flood victims is also important with the changing flood regime in the region. Instituting monitoring and evaluation mechanisms in disaster risk management may also facilitate institutional learning among different agencies. Performance evaluation among different agencies may provide institutional incentives to be become better and accountable. Flood disaster survivors should be part in the evaluation process. Periodic institutional assessment may also foster learning. 5.4 Narrow deliberation The capacity for deliberation is important to ensure that the interests of socially vulnerable groups are represented and different knowledge can be put on the table for discussion and then, ultimately, fair goals are set (Lebel et al. 2005b). The framing of flood-related disasters as a natural event requiring technical risk management has resulted in exclusion of broader public involvement in flood disaster prevention and mitigation. Authorities have just not seen a need or use for public participation except in the instrumental sense of “so they are prepared and will follow orders when the time comes”. The framing of flood disasters as a natural hazard problem requiring technical fixes has several repercussions. First it helps institutionalize the separation of activities of agencies responsible for reducing vulnerabilities and preventing disaster, providing relief and emergency responses, and recovery. Second, it perpetuates the disconnect between flood-related disasters and underlying causes, in particular, alterations to flood plain and riverine ecosystems, and the social processes producing vulnerabilities. Third, it supports uncritically the practise of flood planning and response strategies that are dominated by structural intervention measures. The alternative is to frame flood disaster as a development problem. This would encourage more integrative approaches linking policies and development plans for agriculture, industries, urbanization, and road and water resources infrastructure, among others. The failure for the state to deliver appropriate and reasonable resources and assistance is usually argued with a plea to lack of financial resources and capacity. Exclusion of public in planning is often rationalized in a similar way. The capacity for the current bureaucracy even where goals and visions have been stated more openly to actually engage effectively with wider community is weak. The training of staff, the allocation of budgets (for example for fuel for official cars), emergency budget to match delegated responsibilities, better contingency plans indicating who should do what when and where, and better inter-agency data collection and transmission procedure, among others, are some of the structural barriers. The problems also extend to dealing with risks. It is easier to justify and get politically rewarded for allocations of manpower and resources to activities that yield immediate benefits, as opposed to those that secure a population against poorly understood risks and which, if the event never happens, never resulted in a benefit. Improvements, however, are unlikely unless communities themselves take the initiative. In Ban Luang in our Om Koi case study a special committee was set up to monitor the water level during the monsoon season, propose flood mitigation and prevention plans and seek assistance of the regional office of the Department for Disaster Prevention and Mitigation in Lampang. They also lobbied their Tambon Administrative Organization to actively coordinate with the regional authorities. In Hat Yai a community disaster risk management program was stimulated by externally funded intervention of the Asian Disaster Preparedness Center that collaborated with local government. After the training all the participants coming from Ban Moo 2 formed a village Task Force on Flood Disaster and Emergency. The Task Force has been actively monitoring flood warnings as well as preparing emergency plans in the eventuality of a disastrous flood. The way rules and responsibilities in flood disaster risk management come about can be as important as the final institutions (Lebel & Sinh 2005). Participation is institutionalized in ways that treat it as a process of negotiation and collective problem solving a likely outcome is most stakeholders will view the process as fair they may be quite pragmatic about accepting reduced inequalities in the distribution of involuntary risks, compensation and recovery investments. This could help reduce conflicts around measures taken in the name of flood disaster management. The key appears to be creating arenas for informed participation in planning, exploring intervention options and assessing past experiences. Overall, however, not much is really known about what makes for effective partnerships and division of responsibilities between more centralized disaster management authorities, community organizations and local government. There is always the likelihood that the community or participation discourse is manipulated in ways that shift responsibilities and burdens to community organizations or local governments without corresponding increases in resources or decision-making powers. On the other hand, decentralizing all resources and functions could be very inefficient and lead to n0 single community having access to high level of resources when they are rarely needed. 6 Conclusion In this paper we set out to understand institutional capacities to manage floods so they do not become disasters. While we identified some gaps and basic lack of capacity, much of what we found is better described as “institutionalized incapacities”. In other words, the failures in prevention and mitigation arose from institutional arrangements that could not ensure appropriate capacities to function effectively. This underlines the dual nature of institutions as both causes and solutions to vulnerability and reminds us of the need to go beyond a narrow focus on structural measures. Although our analysis has been critical we find several indications of improved institutional performance. The government and the private sectors have been actively collaborating during emergency for mobilizing resources for relief and emergency assistance. At the province level a committee is formed before the start of the flood season to prepare for the eventual flooding event by providing flood warning system, especially to flood-risk areas. Although the performance of some of these committees in flood-prone provinces, such as in Chiang Mai, needs further improvement, the institutionalization of these committees has been a positive step in preparedness. Attempts to involve the general public are now being explored through the formation of basin river organization, with a mandate that includes a planning unit for flood mitigation and prevention. On the other hand, a number of institutionalized incapacities and practices continue to undermine the provision of assistance and services in reducing the risk of flood disaster. The coordination across administrative hierarchies is very important in the timely delivery of assistance and support before, during and after the crisis. The poor coordination across administrative bodies from the Tambon Administrative Organization to the province delays the delivery of services and assistance. Government line agencies continue to perform within their area of responsibility and jurisdiction without regard to their project’s implication on others. Programs of agencies that address non-structural measures for flood prevention and mitigation are not well linked with structural projects for flood control that are implemented by other state agencies. Watershed, rural and urban uses and planning are not well articulated with waterrelated infrastructure projects for flood control. In remote areas, the marginalized communities are left alone to fend themselves after the disaster due to incomplete implementation of recovery and rehabilitation projects of the state. This is further aggravated by the lack of monitoring and evaluation within the government agencies. The problem is no longer a basic lack of institutional capacity per se as much as bureaucratic norms of organizing, administering and rulemaking that have effectively institutionalized incapacities ensuring effective disaster management will be difficult to achieve. Social mobilization on flood management may be necessary to re-enable these institutions to perform the roles in society for which they were intended – reducing vulnerabilities and risks of flood disasters. Acknowledgements The Packard Foundation through START Institute on Vulnerability, the Asia Pacific Network for Global Environmental Change Research and NOAA are thanked for their financial support. We would like also to thank the three anonymous peer reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions. References ADPC 1998. Study on Role and Functions of ARD Field Operations Centres (FOCs) in Disaster Management in Thailand. Asian Disaster Preparedness Center:, Bangkok, Thailand. ADRC. 1999. Thailand Country Report (1999). Asian Disaster Reduction Center (http://www.adrc.or.jp/countryreport/THA/THAeng99/Thailand99.htm) Assanangkornchai, S., S.-n. Tangboonngam, and J. G. Edwards. 2004. The flooding of Hat Yai: predictors of adverse emotional responses to a natural disaster. Stress & Health 20:81-90. DDPM. 2005. Thailand's Country Report. Research and International Cooperation Bureau, Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation, The Ministry of Interior, Royal Government of Thailand. DDPM. 2004. Handbook of the Ministry of Finance on funds allocation to emergency disaster relief assistance. Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation, Ministry of Interior, Bangkok, Thailand. DDPM 2003. Handbook of the Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation, Ministry of Interior, Bangkok, Thailand. DPW 1998. Master plan for flood protection of 49 areas in the second group of communities. Department of Public Works, Bangkok, Thailand. DWR. 2005. First Memory: 2003 Department of Water Resources. Department of Water Resources, Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, Royal Thai Government. DWR. 2003. Integrated Plan for Water Resources Management in the Ping River Basin. Department of Water Resources, Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, Royal Thai Government ENS. 2001 Thailand could have prevented killer landslides. Environmental News Service, 17 August 2001 (http:ens-newswire.com/ens/aug2001/2001-08-1704.asp) ESCAP. 1999. Regional cooperation in the twenty-first century on flood control and management in Asia and the Pacific. Economic and Social Commission for Asia and Pacific, United Nations. New York. Lakanavichian, Sureeratna. 2001. Forest policy and history in Thailand Working Paper. Research Centre on Forest and People in Thailand: Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Aarhus. Lebel, L. 2005. Institutional dynamics and interplay: critical processes for forest governance and sustainability in the mountain regions of northern Thailand. Pages 531-540 in U. M. Huber, H. K. M. Bugmann, and M. A. Reasoner, editors. Global Change and Mountain Regions: An Overview of Current Knowledge. Springer-Verlag, Berlin. Lebel, L., J. Manuta, and S. Khrutmuang. 2005a. Risk reduction or distribution and recreation? : the politics of flood disaster management in Thailand. USER Working Paper (WP-2004-16). Unit for Social and Environmental Research, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai. Lebel, L., E. Nikitina, V. Kotov, and J. Manuta. 2005b. Reducing the risks of flood disasters: assessing institutionalized capacities and practices. USER Working Paper WP-2005-13. Measuring vulnerability and coping capacity to hazards of natural origin: concepts and methods. Unit for Social and Environmental Research, Chiang Mai University., Chiang Mai. Lebel, L., and B. T. Sinh. 2005. Too much of a good thing: how better governance could reduce vulnerability to floods in the Mekong region. USER Working Paper WP2005-01. Unit for Social and Environmental Research, Chiang Mai. Manuta, J., S. Khrutmuang, and L. Lebel. 2005. The politics of recovery: post-Asian Tsunami reconstruction in southern Thailand. Tropical Coasts July:30-39. Parnwell, Michael; Suriya Veeravonge & Wathana Wongsekiarttirat. 2003. Field report: sustainable livelihoods in Petchabun province. European Commission INCODEV Project. (http://www.ssc.ruc.dk/inco/activities/fieldwork/Petchabun.pdf) Shaw, R. 2004. Community based disaster management: challenges of sustainability. Third Disaster Management Practitioners' Workshop for Southeast Asia. Asian Disaster Preparedness Centre, Bangkok, Thailand. Tanavud, Charlchai; Chao Yongchalermchai; Abdollah Bennui & Omthip Densreeserekul. 2004. Assessment of flood risk in Hat Yai Municipality, Southern Thailand, using GIS. Journal of Natural Disaster Science, Volume 26, Number 1, pp. 1-14. Teeraoranit, Akapob. 2003. Development of Master Plan for Flood Management in Thailand Master Thesis. School of Civil Engineering, Asian Institute of Technology, Pathumthani, Thailand. Tingsanchali, T. S., Seri & Rewtrakulpaiboon, Lersak. 2003. Institutional Arrangements for Flood Disaster Management in Thailand. Strengthening Regional capacity through best practices in Integrated water resources management," Proceedings Volume 2, Technical Papers First Southeast Asia Water Forum, 17-21 November 2003,, Chiang Mai, Thailand. Thailand Research Fund. 2003. Development of Master Plan for Management of Water-related Natural Disasters: Floods, Droughts and Landslides. Bangkok, Thailand Viriyakoson, A., V. Lee, K. Jarernpaisan, and T. Vuttikriviboon. 2001. A preliminary evaluation of economic loss from major flooding in Hatyai and surrounding areas in 2000. Pages 181-190 in S. Viriyakoson, editor. The 2000 Hatyai floods: Problems and management strategies. Prince of Songkhla University, Hat Yai.