Assessing Online Statistics Courses

advertisement

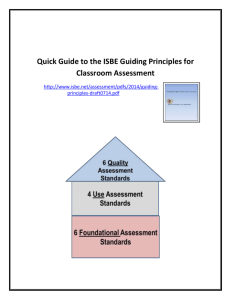

Assessment of Online Statistics Courses1 David W. Stockburger2and S. David Kriska3 2 1 Distribution A, approved for public release, distribution unlimited US Air Force Academy, Center for Educational Excellence, Air Force Academy, CO 80840 3 The Ohio State University, Fisher College of Business, Columbus, OH 43210 Abstract The necessity of clear course goals for assessment of online statistics courses was discussed in the context of current trends in higher education. These trends include the increasing popularity of online courses and the movement toward clear specification of institutional, departmental, and course goals. A content analysis of online statistics course syllabi was conducted to explore the extent to which they met the criteria of quality course goals. The results of the content analysis revealed that about one-third of the course goals would qualify as reasonably clear and assessable. Recommendations included guidelines for quality course goals, backwards course design, and the need for assessed student artifacts for inclusion in a student ePortfolios. Key Words: Online, statistics courses, goals, education 1. Trends in Higher Education Two major trends currently affecting higher education are: 1. a much greater emphasis on assessing student learning beyond the mere memorization of facts and vocabulary and 2. a greater variety of instructional choices available to students. Combined, these trends are changing the assessment of college and university courses. This paper proposes that online courses be assessed relative to their stated goals and then takes an inventory of the goals of a sample of current online statistics courses. 1.1 Colleges and Universities must demonstrate learning The move from a content and instructor centered focus to an emphasis on what students actually learn and how they learn it has changed the way courses are viewed within higher education (Barr and Tagg, 1995; Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U, 2002). Quality courses engage the student with the material and promote skills and attitudes such as critical thinking, ability to express oneself in written and oral communication, and life-long learning, to mention just a few of the proposed learning goals (see AAU&C, 2002). The assumption that if astudents are exposed to the right content and professors, then they will automatically obtain these necessary higherorder skills is no longer automatically accepted. High quality classroom learning experiences are designed not just to cover content, but are based on studies of how students actually learn (National Research Council, 2000). In a effort to head off possible government intervention (Hawthorne, 2008, US Dept of Educ, 2006), accreditation agencies such as North Central Association (NCA) and ABET, Inc (formerly the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology) are requiring institutions and departments to clearly define their learning goals and demonstrate that students are actually achieving the defined goals in order to be accredited. Course goals are mapped onto the institution and departmental goals. For example, The ABET (2008) accreditation for applied science programs includes the following criteria: Each program must have in place: (a) detailed published educational objectives that are consistent with the mission of the institution and these criteria (b) a process based on the needs of the program's various constituencies in which the objectives are determined and periodically evaluated (c) a curriculum and processes that ensure the achievement of these objectives. At the course level it is not expected that all courses will contribute to all higher-order goals, but they must make a contribution to some of them. Many statistics courses are moving into this environment. Using a similar approach, increasing emphasis has been placed on evaluating colleges and universities on the relative degree of student engagement. USA Today (Marklien, 2007) now publishes National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) ratings from participating colleges and universities. Clearly, evaluation of all course will soon encompass aspects of student engagement . 1.2 The number of students taking online courses is increasing In the latest report from the Sloan-CTM foundation (Allen and Seaman, 2007) for the fall semester, 2006, a rate of 19.8% was found for of online enrolment as a percent of total enrolment with a growth rate of 9.7% from the previous year for the on-line enrolment. Most institutions with an enrolment of 3000 or more were engaged or fully engaged with online learning. Response to a survey question “Student demand for online learning is growing” saw 69.9% in agreement and 8.1% disagreeing. The conclusion of Allen and Seaman (2007) was that the percentage of online student enrolment will most likely increase into the near future, but probably at a slower growth rate than the recent past. The increase in online enrolment has resulted in the necessity of making decisions, often without the benefit of much information. From the perspective of the student, a variety of choices are available for learning statistics. These choices include: traditional brick and mortar classroom, blended course, online courses from existing colleges and universities, exclusively online universities, online courses from freestanding organizations, and free online courses. Often these choices are made based on convenience or credentialing requirements. If the student simply needs to check a box with statistics content the choice often is the professor or course that will require the least effort as seen in http://ratemyprofessors.com/. More often than not the choice is made based on the recommendation of other students or advisors. Based on currently available information, it would be difficult to select a course based on an understanding of what knowledge, skills, and abilities will be acquired, how students will be assessed, and what learning experiences will be provided. From the perspective of the university or credentialing organization, the decision of whether to grant credit for the various learning options becomes much more difficult. In the past, credit could often be transferred if the content described in the two course catalogues was basically similar and the reputation of the transferring institution was similar or greater to the credentialing organization. This decision becomes much more difficult when actual student learning must be considered rather than just content coverage and when online courses are so new that reputations have not been sufficiently established. Weigel (2002) has argued that after the development costs of online courses have been recovered, providing access to online learning experiences is relatively inexpensive. That is, it only costs pennies per person to provide worldwide access to existing online courses as long as interaction with a real person is not required. For example, the MITOpenCourseware site offers an online statistics course. If a student completes this course, should it meet a statistics requirement? Can every community college offer a course of this quality? How much interaction with an instructor is necessary for a student to acquire the necessary knowledge, skills, and abilities in an online statistics course? Do all students require the same degree of interaction? These are not easy questions to answer, but the answers have profound implications for the future of higher education and the assessment of online courses. It is not hard to imagine that in the future credit for courses will not be awarded for similar content coverage, but to the extent the goals of the course contribute to meeting the goals of the major or institution. A problem with a goal-focused approach is that just because a course has a stated set of goals, does not mean that the student actually meets those goals. Our belief is that as a result of passing the course, the student must possess an assessed work product or artifact that demonstrates the actual meeting of the course goals. This artifact would most likely be part of a larger collection of artifacts assembled in an ePortfolio. Credit for a course or program would be granted based on demonstrated knowledge, skills, and abilities. A proprietary multiple-choice test would not meet this criterion because only the obtained score could be included as an artifact. 2. Quality Course Goals for Statistics Course goals and outcomes are necessary to begin the assessment process as assessment takes place relative to what was supposed to be accomplished rather than to any absolute standard. After course goals have been established, then questions can be asked about how well the course assessments and learning experiences are aligned with the course goals and whether they contribute to meeting the goals. Good course goals are difficult to write. There is a temptation to summarize course content and add the words “understand” or “comprehend” to the summary and call the result a course goal. The use of the words “understand” and “comprehend” is discouraged because they can mean many different things to different people and do not result in course goals that contribute much to major or institutional goals. For example, what exactly does it mean to understand the sampling distribution? A much more useful goal might be to be able to compare and contrast the sampling distribution of the mean and the sampling distribution of the median. Or better yet, to be able to construct the empirical sampling distribution of any statistic using a statistical simulation program Often the goal in a statistics class is to have the student think like a statistician or appreciate statistical reasoning. Clarifying exactly what statistical thinking entails and how it is different from, say, thinking like a mathematician takes considerable reflection. The question can often be rephrased as how a statistician reacts when faced with a given situation, or what should a student be able to do when facing a similar situation? 2.1 Characteristics of quality course goals (Noyd, et. al., 2008) 2.1.1 Describe What Students Will Learn and Be Able To Do This characteristic describes a goal in student knowledge, skills and abilities rather than instructor actions or content coverage. Generally goals that conform to this characteristic start with “At the end of the course the student will be able to ...” rather than “This course will cover ...” 2.1.2 Are Actionable, Visible, & Measurable Quality course goals are assessable. In general, every course goal should be assessed in some manner or another. If a goal is not directly assessable, such as “Promotes life-long learning”, it might be better considered a hope and included in the teaching philosophy or purpose of the course. 2.1.3 Are Clear & Understandable To Students, As Well As Instructors It is often difficult to write course goals without resorting to acronyms and discipline specific buzz words. Instead of “The student will be able to use MANOVA to ...” it might be better to state the goal as “The student will be able to analyze and interpret complex experimental designs.” 2.1.4 Require High Levels of Thinking Rather than using “list, recall, discuss …” a quality goal uses “critique, plan, compare …” to describe what the student will be able to do at the end of the course. Bloom’s taxonomy is a useful starting point when constructing course goals. 2.2 The Quality Matters (QM) Rubric Because of its growing importance, various organizations have been involved in the assessment of online courses. One that deserves special mention is Quality Matters, an organization which certifies online courses and components (Quality Matters, 2008). This organization has uses eight broad standards in their rubric to include: 2.2.1 2.2.2 2.2.3 2.2.4 2.2.5 2.2.6 2.2.7 2.2.8 Course Overview and Introduction Learning Objectives Assessment and Measurement Resources and Materials Learner Engagement Course Technology Learner Support Accessibility Tthis assessment examines the learning objectives (course goals) as an integral part of its analysis of online courses and in many ways parallels the goals of Noyd, et al. 2.3 Guidelines for Assessment and Instruction in Statistics Education (GAISE) Project The American Statistical Association funded the two GAISE projects in 2003 to provide recommendations for the teaching of introductory statistics (GAISE, 2005). The group that focused on college course provided six recommendations: 2.3.1 2.3.2 2.3.3 2.3.4 2.3.5 2.3.6 Emphasize statistical literacy and develop statistical thinking Use real data Stress conceptual understanding rather than mere knowledge of procedures Foster active learning in the classroom Use technology for developing conceptual understanding and analyzing data Use assessments to improve and evaluate student learning This list of recommendations is a good place to begin when constructing goals for either traditional or online statistics courses. It also provides guidelines for the assessment of the course goals of statistics courses. There is certainly much commonality in the recommendations of Noyd, et al. (2008), Qaultiy Matter (2008), and GAISE. 2.4 A simple rubric for assessing online statistics course goals Originally we had planned on an assessment of learning goals, student assessments, and learning experiences in a sample of online statistics courses. Unless the course goals are reasonably specified, assessment of the other components of the course becomes very difficult, if not impossible. A preliminary search found that many of the online statistics course goals were poorly specified. Realizing it would be difficult to assess student assessments and learning experiences without quality course goals a decision was made to focus exclusively on course goals. The rubric we used to rate course goals is presented below: 1 2 3 4 Content vs. Skills & Abilities Content Skills Higher Cognitive Level Measurable Low Bloom’s Few Measurable High Bloom’s All Measurable Figure 1: Rubric used to assess course goals 3. Survey of Online Statistics Course Goals 3.1 Method We Searched Yahoo with search terms “online statistics course” and took the first 200 hits. If we found a course or courses we searched for the syllabus and then the goals/outcomes/learning objectives. We found 44 different courses in the first 200 hits. Each author rated each course using the rubric to assess course goals. 3.2 Results 3.2.1 Inter-rater agreement The agreement between the two raters was 27% for measurable, 36% for content, and 48% for higher cognitive levels. 3.2.2 Rubric Analysis A histogram of each of the two raters for each rating category is presented below. Rater 1 Content vs. Skills and Abilities Higher Cognitive Level Rater 2 Measurable 3.2.3 Example High Rated Outcome: Students will learn how to solve problems in Elementary Statistics by completing daily homework assignments in problem solving. Students will be able to solve problems using appropriate technology, translating problems from one form to another, using various problem-solving strategies. Students will learn to think critically about Elementary Statistics by applying key theories, concepts, and methods of inquiry in Elementary Statistics to novel problems, to other disciplines, and to situations that require understanding rather than rote memory. 3.2.4 Example Low Rated Outcomes: Sampling distributions, estimation, testing, confidence intervals; exact and asymptotic theories of maximum likelihood and distribution-free methods. This is an online course on medical statistics. A well known software package is used. 4. Discussion While we noted that demands for quality and accountability in higher education is increasing, less than a third of the online statistics courses we sampled had quality goals listed in the syllabus that could be used for assessment purposes. Without stating quality goals, the foundation for demonstrating an effective course is doomed. Without goals, there is no assurance that assessment is on target, and no assurance that students are demonstrating relevant skills. Assessment of student assessments and learning experiences was not attempted at this point. Descriptions of student assessments, when found, were mainly multiple-choice and computation. Even though such assessments are useful for the instructor to judge student progress, we believe that the critical thinking skills are more clearly demonstrated when students must produce a product that involves analysis and writing. Ideally, an online course would first clearly state course goals and objectives, secondly describe how the goals would be assessed, thirdly describe the learning experiences that the student would discover by taking the course, and fourthly, describe an assessed artifact that could be placed in a portfolio or ePortfolio of the student as a result of taking the course. The artifact could be used by the credentialing institution to evaluate whether the student achieved institutional goals by taking the course. 5. Recommendations 5.1 Start with quality goals and outcomes (Noyd, 2008). 5.2 Include an assessment for each learning goal. This recommendation resulted in some questions from the audience about whether it is necessary for all goals, e.g. Life-long learning, to be assessed. After thinking about this issue, we decided that all goals should be assessed. If a goal cannot be assessed, it should be included in the course purpose or philosophy, not as a goal. 5.3 Backwards design the course, starting with the final assessment (Fink, 2003). In an ideal world, course designers would start with course goals, design a final assessment, design assessments that lead to the final assessment, and finally design learning experiences that help the student meet the course goals and perform well on the assessments. In the real world both a top-down and bottom-up course design process normally takes place. 5.4 Align the learning experiences with the course goals and assessments. When assessing online courses, learning experiences will certainly become an important component. They must be evaluated, however, in the context of learning goals and assessments. Active, engaging, and authentic learning experiences are preferred, but if they don’t align with the course goals and assessments, they do not meaningfully contribute to the course. 5.5 Include an assessed product (artifact) that can be included in an ePortfolio. The work product is necessary in order that the student’s achievement of the learning goals can be independently evaluated by a credentialing source. Acknowledgements Colleagues at the Center for Education Excellence at the US Air Force Academy have all contributed to the ideas expressed in this paper. References ABET, Inc. (200) CRITERIA FOR ACCREDITING APPLIED SCIENCE PROGRAMS: Effective for Evaluations During the 2008-2009 Accreditation Cycle. Allen, Elaine and Jeff Seaman (2007). Online Nation: Five Years of Growth in Online Learning. Sloan-C. Available online at <http://sloanconsortium.org/publications/survey/pdf/online_nation.pdf. > Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2002). Greater expectations: A new vision for learning as a nation goes to college. Washington, DC: AAC&U. <http://www.greaterexpectations.org/ > Barr, R. B., & Tagg, J. (1995). From teaching to learning: A new paradigm for undergraduate education. Change, 27, 12-25. Available at <http://critical.tamucc.edu/~blalock/readings/tch2learn.htm> Fink, L.D. (2003). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. GAISE College Report (2005) <http://www.amstat.org/education/gaise/GAISECollege.htm> Hawthorne, Joan (2008) Accountability & Comparability: What's Wrong with the VSA Approach. Liberal Education, Vol. 94, No. 2 Marklein, Mary Beth (2007) Beyond rankings: A new way to look for a college. USA Today, March 11, 2007. <http://www.usatoday.com/news/education/2007-11-04-nsse-cover_N.htm?loc=interstitialskip> National Research Council. (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Noyd, Robert and The Staff of the Center for Educational Excellence (2008). A Primer on Writing Effective LearningCentered Course Goals. US Air Force Academy document. <http://www.psychstat.missouristate.edu/aspx/Documents.aspx> Quality Matters (2008) Inter-Institutional Quality Assurance in Online Learning http://www.qualitymatters.org/ United States. Dept. of Educ. A Test of Leadership: Charting the Future of U.S. Higher Education. Commissioned by Margaret Spellings. Sept. 2006. 28 Mar. 2007 <http://www.ed.gov/about/bdscomm/list/hiedfuture/reports/pre-pubreport.pdf>. Weigel, Van B. (2002) Deep Learning for a Digital Age: Technology’s Untapped Potential to Enrich Higher Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.