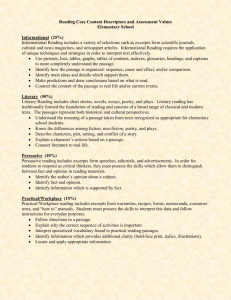

Common Core Reading Standards:

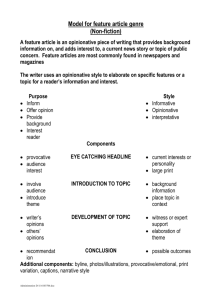

advertisement