[I introduce the study of teaming by talking about how the lecture will

advertisement

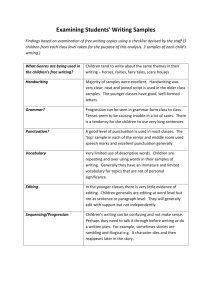

TWS — Lecture 2: Collaborative Writing and Editing Purpose This lecture helps students to function in a team of writers and editors by encouraging them to identify differences between the individual and group writing and editing processes and devise strategies for working with these differences. Justification By asking teams to construct functional collaborative writing situations and to apply editing techniques, the application of two rather large and abstract topics—group writing and editing—is stressed. Team members, then, come away with an understanding of the variety of orderly ways to approach writing and editing and of the importance of a rigorous systematic approach. Giving this lecture after the students have had some team writing experience is preferable because it allows the students to reflect on the methods that they have employed to date and identify differences between their method and a more systematic and comprehensive method. Without this basis of comparison, the concepts covered in the lecture may seem abstract or not immediately applicable and are less likely to be assimilated. Methods A chalk/marker board functions during the group exercises in this lesson as a passive reminder of lecture concepts. Walk Through: Ask the teams how they went about writing their first lab report and how it worked out. They usually volunteer quite a bit of information about their process working or not working, and it seems get the class thinking about process and recognizing that there are different ways of approaching things—some of which work better than others. Discussion: Types of collaborative writing Discussing the differences in collaborative writing styles is not as difficult by this point in the series since the students have already had some experience writing in their teams. Using the students’ comments on how they approached their first team writing experience, I fill in as much as I can on a chart on the board which has three columns: type of writing, who writes, who edits. Eventually some of the chart is filled. Fill in the blanks and discuss the system with the class.1 Cooperative Writing - an author writes, gives drafts to others for editorial input, and revises - this is a lot like the peer editing students have experienced in their freshman composition classes Sequential Writing - several authors write independent sections which are collected and coordinated by one final author - this is how it seems many teams function innately Functional Writing - authors are assigned tasks based on specialization Christine Manion. A Writer’s Guide to Oral Presentations & Writing in the Disciplines. Prentice Hall 2001: 132. 1 Dave Kmiec TWS Lecture 2 V 3.0 - this is broader than sequential writing in that some authors may not be writing at all but instead editing or researching Integrated Writing - authors write independent sections and editing and coordination is done in a group Co-writing - authors write, edit, and revise in a group - this is how some students have worked when partnered in lab settings before Exercise: Considering situations for writing After discussing the stratification, tell the teams to come up with situations where each type of writing would be the most appropriate. Being vague here produces some pleasant surprises as some teams think of a broad range of industrial and commercial situations where others think of academic ones that usually apply to their team specifically. That range is useful when you ask them to present their situations to the class. Evaluating the value of the situations that the teams produce is important. The class typically comes to the conclusion that the type of writing employed is dependent on the technical knowledge and skill required to perform each task. This can be used to begin talking about levels of editing. Discussion: Levels of peer (and self) editing Students who aren’t constantly exposed to the writing and editing processes are often intimidated by the less technical side of the reporting process. Peer editing is much less intimidating if it is done in a systematic fashion: by stratifying the often haphazard error identification and correction process into four levels. Content—this level assesses the technical accuracy of content and is typically conducted by someone within the field Organization—this level studies the ordering of main points and assesses its contribution to or detraction from the reader’s ability to follow the text to its logical conclusion Style—this level determines whether the tone, style, persona, etc. are effective and appropriate for the text’s intended audience Mechanics—this level compares the mechanical and grammatical structure of the text with appropriate standard form Discussion: Organization Talk about the idea of beginning, middle, and end—or introduction, body, conclusions; or any of a hundred other ways to phrase it—and the logical progression of information. Spend time talking about how order can improve the readability of a document. You may want to suggest that, if they’re having trouble making connections or understanding what they’re reading in a peer editing situation, they should identify what the content and function of each sentence is and make sure that those content pieces are in the correct order. To do this, reduce sentences to meta-labels, put the information labels in order, and then re-associate. (I find engineers see this as “easier than putting thirty-word sentences in order”; I find information and computer scientists love this method.) Dave Kmiec TWS Lecture 2 V 3.0 Exercise: Editing for order In groups, have them work on a technical paragraph which has some organizational issues. (A sample can be found in the appendix.) Then go over it as a class. Discussion: 10 ways to interpret "awk." or 10 things to say instead of "awk." Another skill that is essential to teams that peer edit is the ability to give specific and useful feedback.2 Discuss why getting a paper back from a professor or a peer reviewer that simply says “there’s something wrong here” or “this is awkward” is not helpful. Then discuss some ways to quantify awkwardness: Place the main idea first Use standard sentence order Use the active voice if possible (3 methods) o Move the person acting out of a prepositional phrase o Supply a subject o Substitute passive verbs with active ones Employ parallelism Write sentences 12 to 25 words in length Use there are sparingly but use it for emphasis or to avoid the verb exist Avoid nominalizations Avoid strings of choppy sentences Avoid wordiness Avoid redundant words or phrases This list, though by no means comprehensive, identifies typical errors that may result in awkward phrasing and is equally useful when editing as when looking at vague editing comments. Exercise: Giving constructive editing comments In groups, have them work on a series of sentences which could benefit from the application of items on this list. (If you are short on time, you may want to tell them to list which of the above rules they would employ rather than actually ask them fix the sentences.) 2 Vague, and consequentially unhelpful, editing suggestions is one of the biggest problems in the peer review process—especially in classes of non-writing majors. While I’m sure the concept of bringing this to the students’ attention in order to stimulate them to provide more specific responses is not new, the resource that first brought my attention to this activity is: G.A. Neubert & S.J. McNelis. “Peer Response: Teaching Specific Revision Suggestions.” English Journal 79 (1990): 52-56. Dave Kmiec TWS Lecture 2 V 3.0