marine snow-teacher`s notes

advertisement

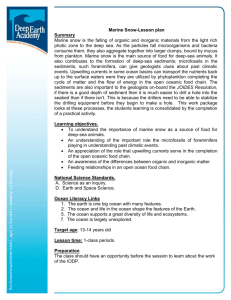

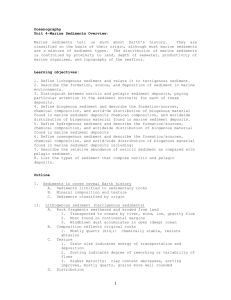

Marine Snow- Teacher’s Notes Introduction Marine snow is organic material, including dead animals, plants and fecal matter and inorganic particles such as sand and soot that floats down to the seabed just as leaves and decaying material fall on to a forest floor. It is referred to as marine snow because it looks like white fluffy bits, it was first noticed by the explorer William Beebe as he observed it from his bathysphere. The relevance of marine snow The continuous falling of these small particles from the sunlit photic zone to the deep aphotic zone provides a source of food plus carbon and nitrogen for scavenging animals that live in the deep sea. It is the major determinant of abundance and activity of large and small deepsea animals. The process The consumption of the organic material begins almost straight away; it is consumed by microbes, zooplankton and other filter feeding animals, especially in the first 1000m of its journey. As the marine snow falls the particles aggregate together and increase in size, they are held in place by sticky nets of mucus made by plankton. The oceanic currents determine the speed of the particles descent, but it is generally slow, perhaps 10 to a few 100m per day. They travel sideways (imagine a balloon dropped from a height) and often land several miles away from where they started. The amount of marine snow falling varies with the seasons; during the spring phytoplankton blooms the productivity is greater. It also varies between ocean basins. Ooze The small percentage of material not consumed in the shallower waters becomes incorporated into the muddy “ooze” blanketing the seafloor, where it is further decomposed through biological activity. About three-quarters of the deep ocean floor is covered in this thick, smooth ooze. The ooze collects as much as six meters (20 feet) every million years. On average it is ~300m (950 feet) thick but can be up to nearly 10 km (6.2 miles). At areas of young crust, for example near a spreading ridge, the amount of sediment is less than at older parts of the oceanic crust. Microfossils and foraminifera in the sediments Sediment also comprises of millions of tiny microfossils such as diatoms, radiolarians and foraminifera. These are the remains of creatures that had skeletons made of carbonate or silica. Their sensitivity to environmental change, wide distribution and abundance of shells make them a valuable tool for understanding past climatic events especially as the benthic (bottom) foraminifera record is more than 550 million years old. Because of the length of time a foraminifera species exists is geologically brief (around 5-15 million years), the shells are also very useful for determining the age of sediments in which they occur. Upwelling In some ocean basins there is a strong upwelling current which brings the nutrients from the bottom sediments up through the water column to the phytoplankton in the photic zone. Here they feed on the carbon and nitrogen, completing the cycle of matter and flow of energy in the open ocean food chain. Basic food chain Nutrients - Phytoplankton – Zooplankton – Invertebrates - Vertebrates. Sediments and drilling on the JOIDES Resolution The sediments are also important to the geologists and drillers on-board the JR. If there is a good depth of sediment then it is much easier to drill a hole into the seabed than if there isn’t. This is because the drillers need to be able to stabilize the drilling equipment before they begin to make a hole.