Breathing pattern delivered by an automatic mode of mechanical

advertisement

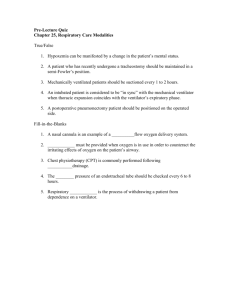

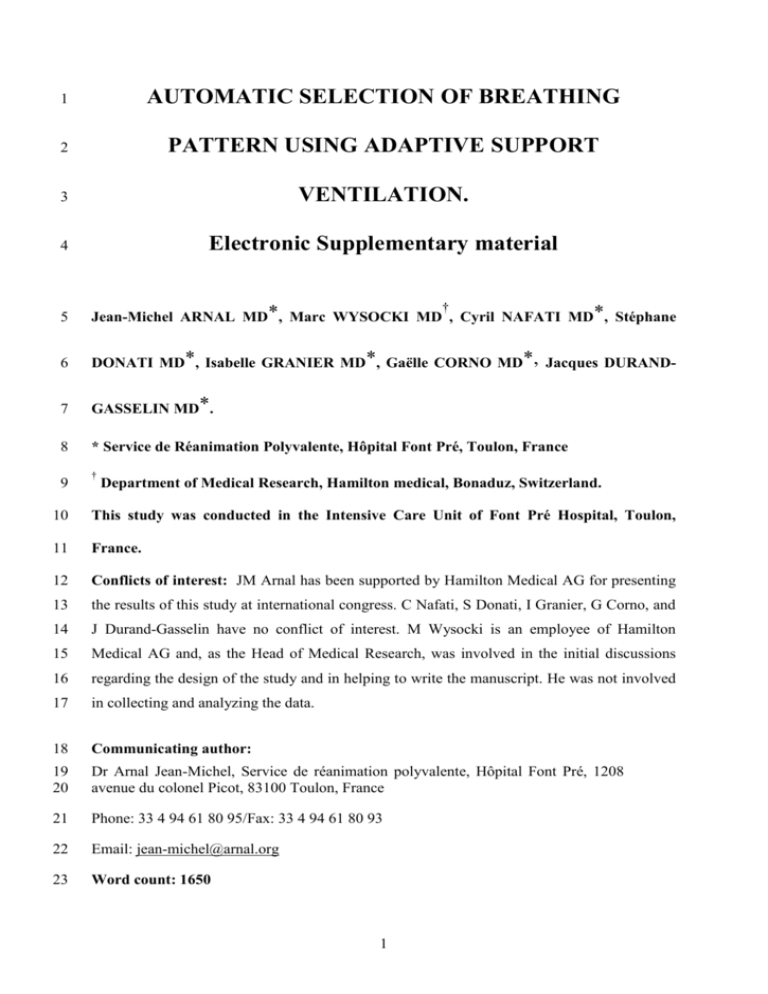

1 AUTOMATIC SELECTION OF BREATHING 2 PATTERN USING ADAPTIVE SUPPORT 3 VENTILATION. 4 Electronic Supplementary material 5 Jean-Michel ARNAL MD*, Marc WYSOCKI MD , Cyril NAFATI MD*, Stéphane 6 DONATI MD*, Isabelle GRANIER MD*, Gaëlle CORNO MD*, Jacques DURAND- 7 GASSELIN MD*. 8 * Service de Réanimation Polyvalente, Hôpital Font Pré, Toulon, France 9 † † Department of Medical Research, Hamilton medical, Bonaduz, Switzerland. 10 This study was conducted in the Intensive Care Unit of Font Pré Hospital, Toulon, 11 France. 12 Conflicts of interest: JM Arnal has been supported by Hamilton Medical AG for presenting 13 the results of this study at international congress. C Nafati, S Donati, I Granier, G Corno, and 14 J Durand-Gasselin have no conflict of interest. M Wysocki is an employee of Hamilton 15 Medical AG and, as the Head of Medical Research, was involved in the initial discussions 16 regarding the design of the study and in helping to write the manuscript. He was not involved 17 in collecting and analyzing the data. 18 Communicating author: 19 20 Dr Arnal Jean-Michel, Service de réanimation polyvalente, Hôpital Font Pré, 1208 avenue du colonel Picot, 83100 Toulon, France 21 Phone: 33 4 94 61 80 95/Fax: 33 4 94 61 80 93 22 Email: jean-michel@arnal.org 23 Word count: 1650 1 1 Methods: 2 Patients: 3 Patients admitted between January and August 2004 to the 11-bed adult general intensive care 4 unit of Font Pré Hospital (Toulon, France) were included if they were invasively ventilated. 5 Patients for whom leaks were an issue (noninvasive ventilation and broncho-pleural fistula) 6 were not included. All patients were ventilated with a GALILEO Gold ventilator (Hamilton 7 Medical, Bonaduz, Switzerland) using ASV as the primary mode. 8 Ethical considerations: 9 This observational and descriptive study has been approved by the ethic committee of the 10 French Society of Critical Care (SRLF). Before starting the study, ASV was used in the unit 11 as a routine clinical care for more than two years and 90% of the patients received ASV as a 12 default mode. Because the study was purely observational and descriptive and involved no 13 intervention, the investigators believed possible to waive the informed consent. Information to 14 the patients and the families regarding the ventilatory treatment was given according to the 15 general practice in the unit. 16 Definitions: 17 For any given patient, each ventilation-day was categorized using one of the five following 18 clinical conditions: 19 Normal lungs defined by no underlying respiratory disease, a normal chest X-ray, and 20 a PaO2/FiO2 ratio ≥ 300 mmHg. 21 ALI/ARDS as defined by the American–European Consensus Conference [1]. 22 COPD as defined by the GOLD criteria [2]. 23 Chest wall stiffness included patients with cyphoscoliosis, morbid obesity or a 24 neuromuscular disorder [3]. 2 1 Acute respiratory failure (ARF) defined by a PaO2/FiO2 ratio ≤ 300 mmHg without the 2 ARDS/ALI criteria from the American–European Consensus Conference [1]. 3 For any given patient, each ventilation-day was categorized as a passive or an active 4 ventilation-day, the latter being defined by a patient’s spontaneous RR being > 75% of the 5 total RR. 6 Daily categorization makes it possible for a given patient to be categorized differently based 7 on his changing condition. As an example, a patient might be categorized as “passive ARDS” 8 on the first days after admission, while he might be categorized as “active normal lungs” on 9 the following days, if he improves. 10 The categorization was done daily (including public holidays and weekends) between 8 to 9 11 a.m. based on the medical team’s consensual decision, taking into account the medical 12 history, chest examination, daily chest X-ray, daily arterial blood gases, and any other exams 13 that may have been performed (e.g., CT scan, bacteriologic sample). 14 ASV description and settings: 15 ASV has been fully described in previous papers [4, 5, 6]. In short, MV is set by the clinician 16 and controlled through a VT–RR combination based on breath-by-breath estimation of RCexp 17 [7, 8] according to the minimal work of breathing concept developed by Otis [9]. At the onset 18 of mechanical ventilation, the ventilator delivers three test breaths, during which RCexp is 19 determined from the expiratory flow volume curve [7, 8]. Subsequently, and on a breath-by- 20 breath basis, two simultaneous closed-loop controls continuously regulate 1) Pinsp, to achieve 21 the target VT, and 2) inspiratory and expiratory times (TI and TE), to achieve the target RR in 22 passive patients and in active patients when the patient’s rate is below the target RR. 23 To avoid extreme and potentially dangerous values of VT and RR, ASV applies, on a breath- 24 by-breath basis, a safety window for target VT and RR values. The minimal target VT is 25 defined as twice the anatomical dead space estimated from the predicted body weight (PBW). 3 1 The maximal target VT is defined as the maximal clinician-set pressure times the dynamic 2 compliance of the total respiratory system. The minimal value for the target RR is 5 3 breaths/min. The maximal value for the target RR is defined as the ratio 20/RCexp. MV is set 4 by the clinician and expressed as a percentage (%MV) of a physiological MV (0.1 L/kg of 5 PBW/min in the adult patient): 100% MV being equal to 0.1 L/kg PBW/min, i.e., 7 L/min for 6 70 kg of PBW. The patient PBW is entered through a specific control in the ASV control 7 panel. In the present study PBW was calculated according to height and gender [10]. In active 8 and passive patients, the starting %MV was initially set at 110% (i.e., plus 10% above normal 9 MV to compensate for increased dead space when a heat and moisture exchanger is inserted 10 between the ventilator pneumotachograph and the endotracheal tube). The %MV was later 11 adjusted according to the desired PaCO2 in passive patients and according to the clinical 12 condition in active patients: 13 In passive patients, the target PaCO2 was 38 – 42 mmHg and 40 – 45 mmHg in normal 14 lungs and ALI/ARDS respectively. In ALI/ARDS patients a permissive respiratory acidosis 15 down to a pH of 7.25 (including maximal reduction of the apparatus dead space) was allowed 16 to keep the total inspiratory pressure below or equal to 35 cmH2O [11]. In passive patients 17 with chronic respiratory disease, the %MV was adjusted to normalize the arterial pH between 18 7.38 and 7.42. In all passive patients the target PaCO2 was refined to 30 – 35 mmHg in cases 19 of increased intracranial pressure. 20 In active patients, the %MV was adjusted according to clinical conditions as in pressure 21 support mode. In cases of insufficient support evidenced by a high RR (> 30 breaths/min), 22 accessory muscle activation, etc., the %MV was increased whatever the PaCO2 level. In cases 23 of sufficient support evidenced by a RR below 20 breaths/min without clinical signs of 24 respiratory distress, the %MV was progressively reduced to 110%. 25 Other settings 4 1 All patients were orally intubated and tracheotomized when necessary for weaning. The 2 positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) level was set at 5 cmH2O in normal lung patients and 3 passive obstructive pulmonary disease patients (COPD) . In active COPD patients, PEEP was 4 adjusted by clinical inspection of respiratory muscle activation to trigger the breath [12]. In 5 passive ALI/ARDS patients, PEEP was set at 2 cmH2O above the lower inflection point 6 determined from a quasi-static pressure-volume curve of the respiratory system (P/V Tool®, 7 Hamilton Medical, Bonaduz, Switzerland) repeated twice a day. When a lower inflection 8 point was absent, PEEP was set below 10 cmH2O. In active ALI/ARDS patients, the FiO2– 9 PEEP combination applied by the ARDS Network was used [13]. Otherwise the FiO2 was set 10 at the minimal value to reach a PaO2 between 60 and 70 mmHg in ALI/ARDS and COPD 11 patients and between 80 and 100 mmHg in other patients. 12 Failure of ASV 13 ASV failure was defined by one of the following conditions: 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 1) Total inspiratory pressure (Pinsp + PEEP) ≥ 35 cmH2O, allowing user to manually adjust VT or inspiratory pressure. 2) Broncho-pleural fistula onset during ventilation, because of lack of information about the accuracy of RCexp measurement in cases of leak. 3) Abnormal respiratory rhythms, because of the ASV response-time which can be much slower than the patient’s rhythm. 4) Patient-ventilator asynchrony defined clinically and on the pressure-flow traces 21 [14], allowing user to manually adjust inspiratory pressure. 22 Patients who failed ASV were switched to a volume-controlled or pressure support mode. 23 Weaning with ASV 24 The indication for a T-tube trial was screened daily and the test initiated and monitored by the 25 nurse caring for the patient if all the following criteria were met: 5 1 Patient actively breathing (defined by a patient’s spontaneous RR > 75% of the total RR). 2 PaO2/FiO2 ratio > 200 mmHg 3 PEEP ≤ 5 cmH2O 4 %MV setting ≤ 130% 5 Pinsp ≤ 20 cmH2O 6 Adequate coughing during suctioning 7 No infusion of sedative or vasopressor agents [15] 8 If the previous criteria were met, the ventilator mode was switched to a CPAP setting of 5 9 cmH2O to measure the RR/VT ratio over a 5-minute period. A RR/VT ratio < 105 breaths/min 10 per liter was required to start the T-tube trial. 11 A one-hour (two-hour for patients with previous chronic respiratory disease) T-tube trial was 12 performed by disconnecting the patient from the ventilator, suctioning the patient, deflating 13 the cuff of the endotracheal prosthesis, and providing oxygen supplementation to maintain the 14 arterial oxygen saturation above 95%. 15 The T-tube trial was defined as a failure and the patient reconnected to the ventilator with the 16 previous settings if at least one of the following criteria was present [15]: 17 1) RR > 35 breaths/min sustained for at least 5 minutes 18 2) Arterial oxygen saturation < 90% despite oxygen supplementation 19 3) Heart rate ≥ 140 beats per minute or a sustained change in the heart rate of 20% in 20 either direction 21 4) Systolic blood pressure > 180 mmHg or < 90 mmHg 22 5) Increased anxiety and/or diaphoresis 23 After three T-tube test failures, the patient was either tracheotomized or extubated and given 24 immediate non-invasive ventilation support. If the T-tube test was successful (i.e., the above 25 criteria were absent), the patient was extubated. 6 1 Data collection: 2 Recording was done at 6 a.m., with arterial blood gas analysis by an independent investigator 3 who did not participate in the categorization. This time of day was chosen to avoid ventilatory 4 perturbation due to nursing procedures. Ventilator settings (PBW, %MV, PEEP, and FiO2), 5 breathing pattern (VT, total and spontaneous RR, TI, TE), and respiratory mechanics 6 parameters were read from the ventilator display along with arterial blood gas results (pH, 7 PaO2, PaCO2). Airway pressure and flow were measured using the proximal 8 pneumotachograph (single-use flow sensor, PN 279331, Hamilton Medical, Bonaduz, 9 Switzerland, linear between -120 and 120 L/min with a ±5% error of measure) inserted 10 between the endotracheal tube and the Y-piece of the ventilator circuit. VT was obtained by 11 integration of the flow signal. In passive patients, static compliance (Cstat) and inspiratory 12 resistance (Rins) were measured using the least square fit method [16]. RCexp was 13 automatically calculated on a breath-to-breath basis as the ratio between the volume and the 14 simultaneous expiratory flow measured at the point corresponding to 75% of the expiratory 15 tidal volume [8, 9]. 16 Statistical analysis: 17 Values are given as medians with their 25th and 75th quartiles. Comparisons were done using a 18 nonparametric analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences were considered significant when 19 p < 0.05. When significant differences were observed, two-by-two multiple comparisons were 20 performed using Dunn’s method (SigmaStat, version 3.0, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL USA). 21 22 23 24 25 7 1 2 3 References: 1) Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, Lamy M, Le Gall 4 JR, Morris A, Spragg R (1994) Report of the American-European Consensus 5 Conference on acute respiratory distress syndrome: definitions, mechanism, relevant 6 outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Consensus Committee. Am J Respir Crit 7 Care Med 149:818-824 8 2) Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, Fukuchi Y, Jenkins 9 C, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Van Weel C, Zielinski J (2007) Global strategy for the 10 Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPD- 2006 Update. Am J Respir Crit 11 Care Med may [Epub ahead of print] 12 13 14 15 16 17 3) MacDuff A, Grant IS (2003) Critical care management of neuromuscular disease, including long term ventilation. Curr Opin Crit Care 9:106-12 4) Brunner JX, Iotti GA (2002) Adaptive Support Ventilation (ASV). Minerva Anesthesiol 68:365-368 5) Campbell RS, Branson RD, Johannigman JA (2001) Adaptive Support Ventilation. Respir Care Clin N Am 7:425-440 18 6) Tassaux D, Dalmas E, Gratadour P, Jolliet P (2002) Patient-ventilator interactions 19 during partial ventilatory support: A preliminary study comparing the effects of 20 adaptive support ventilation with synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation plus 21 inspiratory pressure support. Crit Care Medicine 30:801-807 22 7) Brunner JX, Laubsher TP, Banner MJ, Iotti G, Brashi A (1995) Simple method to 23 measure total expiratory time constant based on passive expiratory flow-volume 24 curve. Crit Care Med 23:1117-1122 8 1 8) Lourens MS, Van Den Berg B, Aerts JG, Verbraak AFM, Hoogsteden HC, Bogaard 2 JM (2000) Expiratory time constants in mechanically ventilated patients with and 3 without COPD. Intensive Care Med 26:1612-1618 4 5 9) Otis AB, Fenn WO, Rahn H (1950) Mechanics of breathing in man. J App Physiol 2:592-607 6 10) Devine BJ (1974) Gentamicin therapy. Drug Intell Clin Pharm 8:650-655 7 11) Prat G, Renault A, Tonnelier JM, Goetghebeur D, Oger E, Boles JM, L’Her E (2003) 8 Influence of the humidification device during acute respiratory distress syndrome. 9 Intensive Care Med 29:2211-2215 10 11 12) Brochard L (2002) Intrinsic (or auto-) positive end-expiratory pressure during spontaneous or assisted ventilation. Intensive Care Med 28:1552-1554 12 13) Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network (2000) Ventilation with lower tidal 13 volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute 14 respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 18:1301-1308 15 16 14) Geogopoulos D, Prinianakis D, Kondili E (2006) Bedside waveforms interpretation as a tool to identify patient-ventilator asynchronies. Intensive Care Med 32:34-47 17 15) Ely EW, Baker AM, Dunagan DP, Burke HL, Smith AC, Kelly PT, Johnson MM, 18 Browder RW, Bowton DL, Haponik EF (1996) Effect on the duration of mechanical 19 ventilation of identifiying patients capable of breathing spontaneously. N Engl J Med 20 335:1864-1869 21 16) Iotti GA, Braschi A, Brunner JX, Smits T, Olivei M, Palo A, Veronesi R (1995) 22 Respiratory mechanics by least squares fitting in mechanically ventilated patients: 23 applications during paralysis and during pressure support ventilation. Intensive Care 24 Med 21: 406-413 9