Barrymore Castle, Castlelyons. The valley of the Bride extends from

advertisement

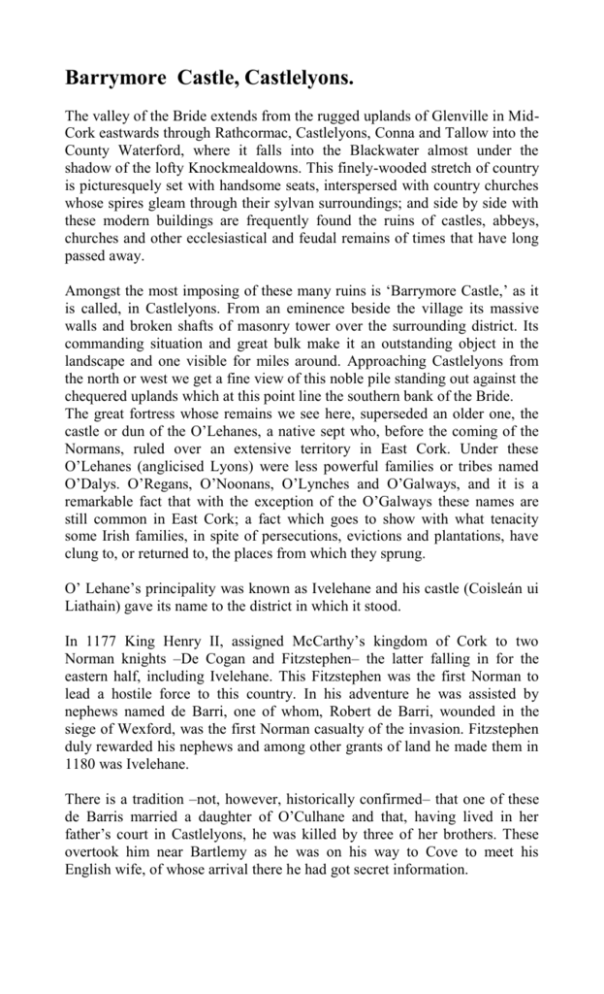

Barrymore Castle, Castlelyons. The valley of the Bride extends from the rugged uplands of Glenville in MidCork eastwards through Rathcormac, Castlelyons, Conna and Tallow into the County Waterford, where it falls into the Blackwater almost under the shadow of the lofty Knockmealdowns. This finely-wooded stretch of country is picturesquely set with handsome seats, interspersed with country churches whose spires gleam through their sylvan surroundings; and side by side with these modern buildings are frequently found the ruins of castles, abbeys, churches and other ecclesiastical and feudal remains of times that have long passed away. Amongst the most imposing of these many ruins is ‘Barrymore Castle,’ as it is called, in Castlelyons. From an eminence beside the village its massive walls and broken shafts of masonry tower over the surrounding district. Its commanding situation and great bulk make it an outstanding object in the landscape and one visible for miles around. Approaching Castlelyons from the north or west we get a fine view of this noble pile standing out against the chequered uplands which at this point line the southern bank of the Bride. The great fortress whose remains we see here, superseded an older one, the castle or dun of the O’Lehanes, a native sept who, before the coming of the Normans, ruled over an extensive territory in East Cork. Under these O’Lehanes (anglicised Lyons) were less powerful families or tribes named O’Dalys. O’Regans, O’Noonans, O’Lynches and O’Galways, and it is a remarkable fact that with the exception of the O’Galways these names are still common in East Cork; a fact which goes to show with what tenacity some Irish families, in spite of persecutions, evictions and plantations, have clung to, or returned to, the places from which they sprung. O’ Lehane’s principality was known as Ivelehane and his castle (Coisleán ui Liathain) gave its name to the district in which it stood. In 1177 King Henry II, assigned McCarthy’s kingdom of Cork to two Norman knights –De Cogan and Fitzstephen– the latter falling in for the eastern half, including Ivelehane. This Fitzstephen was the first Norman to lead a hostile force to this country. In his adventure he was assisted by nephews named de Barri, one of whom, Robert de Barri, wounded in the siege of Wexford, was the first Norman casualty of the invasion. Fitzstephen duly rewarded his nephews and among other grants of land he made them in 1180 was Ivelehane. There is a tradition –not, however, historically confirmed– that one of these de Barris married a daughter of O’Culhane and that, having lived in her father’s court in Castlelyons, he was killed by three of her brothers. These overtook him near Bartlemy as he was on his way to Cove to meet his English wife, of whose arrival there he had got secret information. Be this as it may, the de Barris had more than the hostility of the O’Lehanes to contend with in establishing themselves in Ivelehane. Fitzstephen’s son disputed their right, and succeeded in ousting them for a time. However, in the year 1185, near Curraglass, on the borders of Cork and Waterford the young Fitzstephen was killed. The victorious de Barri then remained in undisputed possession of Ivelehane, and from him descended the long line of powerful nobles who, for 600 years, reigned in Castlelyons, and whose sway extended over a large part of Cork County. These Norman rulers of ancient Ivelehane are in English records styled Lords of Olethan or Oleighan, corruptions of O’Lehane, and their court was variously known as Castle Olethan, Castellaythan, Castle Oleighane and, in modern times, Castlelyons. About the fifteenth century the title ‘An Barrach Mór’ (Barrymore) was given to the reigning lords of Olethan to distinguish them from nobles of the same name in other parts of Cork County. Down through the centuries these lords of Olethan played active parts in different phases of the changing times through which our country passed. They ranked among the highest dignitaries, holding positions of great power and influence as county sheriffs, justices, military captains and members of parliament, and in later times as earls and peers of the realm, positions that in arbitrary times conferred almost unchallenged authority over life and death. Their castle in Castlelyons was, for the most part, a seat of foreign power, a stronghold of foreign domination, and, in the battle of the Confederate Catholics, a bulwark of the foreign garrison. No wonder the great castle had an unsavoury reputation amongst the peasantry. Many dark deeds were associated in their minds with its history. Even to the present day stories are locally told of the ‘murdering hole,’ a mysterious apartment the fortress was supposed to contain and through which, it was asserted, obnoxious persons were sent to terrible deaths. Upon what foundations, real or imaginary, this gruesome chamber rested, we cannot now say. In days when human life was held cheap, when autocratic power was frequently abused, and when mercy seldom tempered either justice or injustice, it is easy to understand how in times like these an oppressed people could, on slight cause, invest their masters with extravagant forms of wickedness. However this may be, the fact remains that the Murdering Hole and its associated horrors are to this day deeply rooted realities in the traditions of the peasantry over whose ancestors the lords of Olethan ruled. Great and powerful personages often filled the halls of Castlelyons Castle, assembled there in warlike council or in convivial relaxation. Late in 1641 we find, among others, met round its social board Lord Broghill, Lord Muskerry, Lord Dungarvan, and the famous Lord Boyle, first Earl of Cork. In the midst of the festivities a messenger arrived from Dublin with dispatches for Lord Boyle, informing him of the outbreak of the rebellion in the north. This was the first news of that rising to reach Munster. Boyle, not wishing to mar the good cheer, kept the intelligence to himself till dinner was over. There was then an abrupt and hurried leave-taking. Some of those seated side by side in friendship that evening next fought in opposing ranks of war. Lord Muskerry took a leading part on the Catholic side, while Broghill and Dungarvan were amongst the most ruthless of the Parliamentary generals. During these Confederate wars Castlelyons Castle was a base of operations against the Catholics, and from it frequent attacks were launched across the Blackwater on Condon’s castles and lands. In one such attack, in May, 1642, Lord Barrymore took a Condon stronghold and, in addition to the captured garrison, he put to the sword one hundred women and children found on it, amongst them being Condon’s wife, Lord Barrymore’s own grand-aunt. In July of the same year, Lord Barrymore took Cloughlea, Condon’s chief castle when he again put the garrison to the sword. Nor were the Catholic leaders more merciful. When Lord Castlehaven, the Confederate general, took the castle of Annagh in 1645, he, too, put the captured garrison to the sword, though the castle had been surrendered to him on promise of quarter. This year (1645) saw a series of successes for the southern Catholics. Enemy fortresses fell quickly before Lord Castlehaven or surrendered at his approach. An attempt to take Castlelyons Castle was one of the few reverses his army met with that year. When the confederate horse, advancing from Fermoy, had got within a few miles of the fortress, Lord Broghill, issuing from it with a force of cavalry, posted himself in their way. By a pretended flight he drew the Irish in pursuit when, suddenly wheeling about, he fell on their disordered ranks and utterly routed them. In the year 1700, the castle was renovated and greatly enlarged. This was an undertaking that would not appear to have involved any very great financial outlay, as the work-men employed were paid, it is said, at the rate of one and a half pence per day. The era of trades unionism was then far in the future. This great structure, with all its contents and appurtenant courts and buildings, was accidentally burned to the ground in July, 1771. The chutes on top were being repaired by two tinkers who, when called down to refreshments, left heated soldering irons lying on some woodwork behind them. On their return the top of the castle was on fire; the heat of the midsummer day aided the spread of the flames, which soon got beyond control. The burning debris smouldered on for two months. The Lord Barrymore of the day was at the time of the burning away in England mortgaging portions of his estates. He was unable to undertake the rebuilding of the castle and its destruction severed the immediate connection of the Barrymores with Castlelyons, whose headquarters for centuries it had been. Sic transit Gloria mundi. That once noble keep, ‘embattled high and proudly towered.’ Is now a shapeless dismantled wreck. Its walls, once draped with ermine and hung with trophies of war, are now naked, weather-beaten and scathed by time and storm; while the halls that rang with martial music and clang of arms and revel loud and long are silent, grassgrown and lorn. Yet even in its loneliness and decay there is a pride, a majesty about this great ruin, boldly rising, grim and gaunt, about its lofty perch, looking down with contempt, as it were, upon a degenerate world where petty rustics plying their toils obscure, take the place of bannered hosts of knights and heroes who peopled the plains of old. See also “A Normans Atonement “ on page 428 (ed)